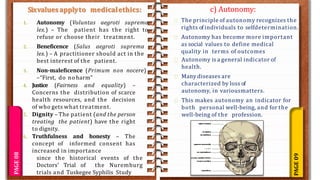

This document outlines the contents of a lecture on research methodology and biostatistics delivered by Prof. Sonali R. Pawar. It covers various topics in medical ethics including: the history of medical ethics traced back to guidelines like the Hippocratic Oath; core values like autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence; concepts like informed consent and confidentiality; criticisms of orthodox medical ethics; the importance of communication and guidelines/ethics committees; cultural concerns and conflicts of interest. It also discusses principles like double effect and end of life issues like futility.