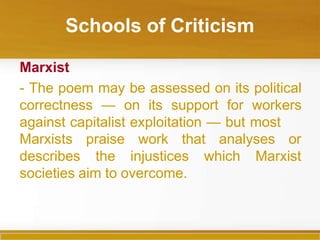

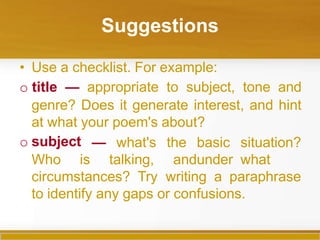

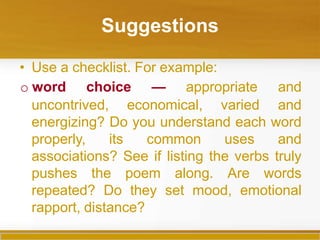

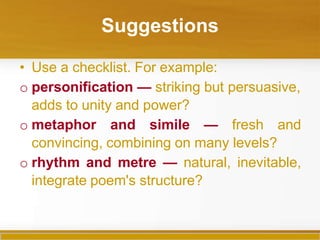

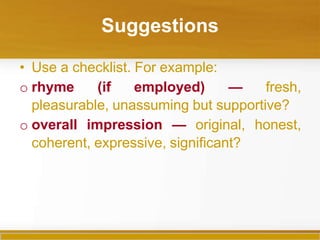

This document provides an overview of literary criticism and its various approaches. It discusses how literary criticism can help poets evaluate and improve their own work by introducing them to different themes, cultures, and critical lenses. Various schools of criticism are described, including traditional, new criticism, rhetorical, stylistic, and more. The document concludes by suggesting poets practice self-critique using checklists and by gaining exposure to different literary criticism to strengthen their own writing.