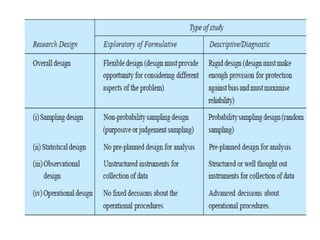

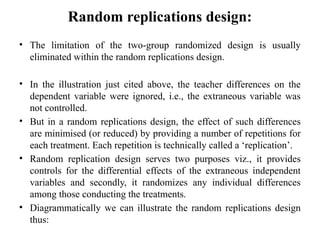

The document provides a comprehensive overview of research design, emphasizing its importance as a blueprint for collecting, measuring, and analyzing data. It discusses key components such as sampling design, observational design, and statistical design, alongside operational definitions to ensure consistent data collection. Additionally, it outlines various research designs for exploratory, descriptive, and hypothesis-testing studies, stressing the necessity for careful planning and minimizing bias to obtain reliable results.