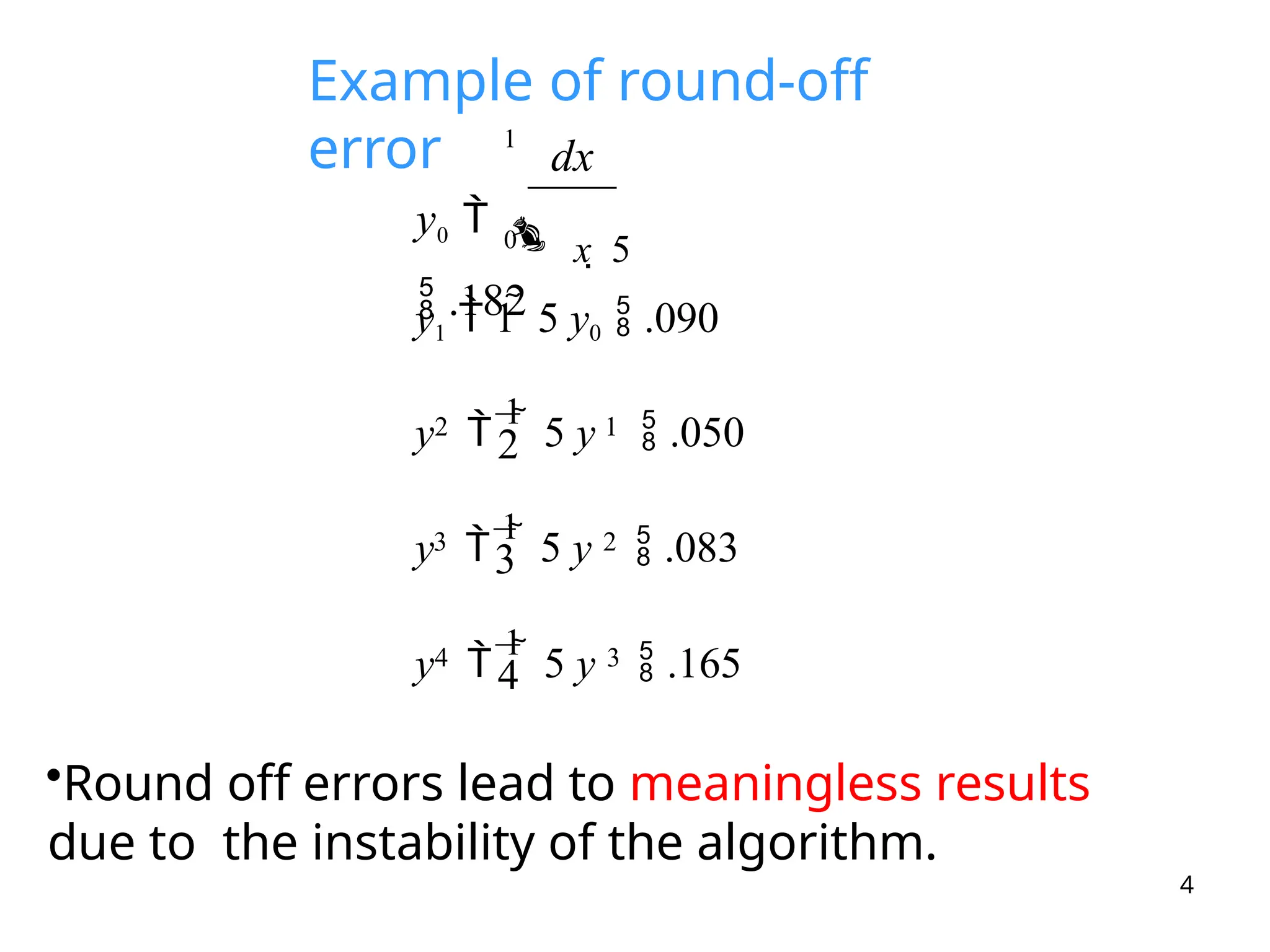

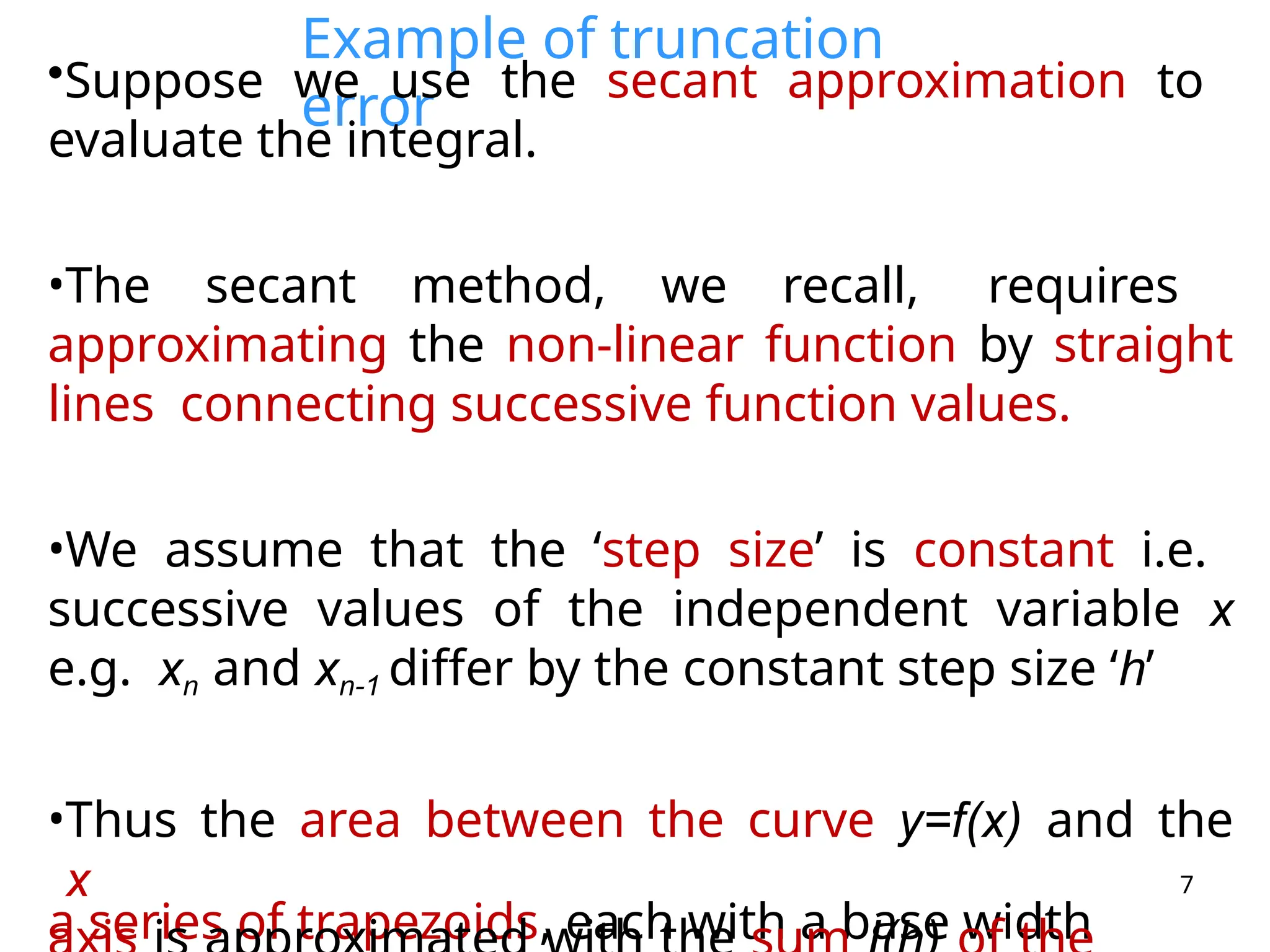

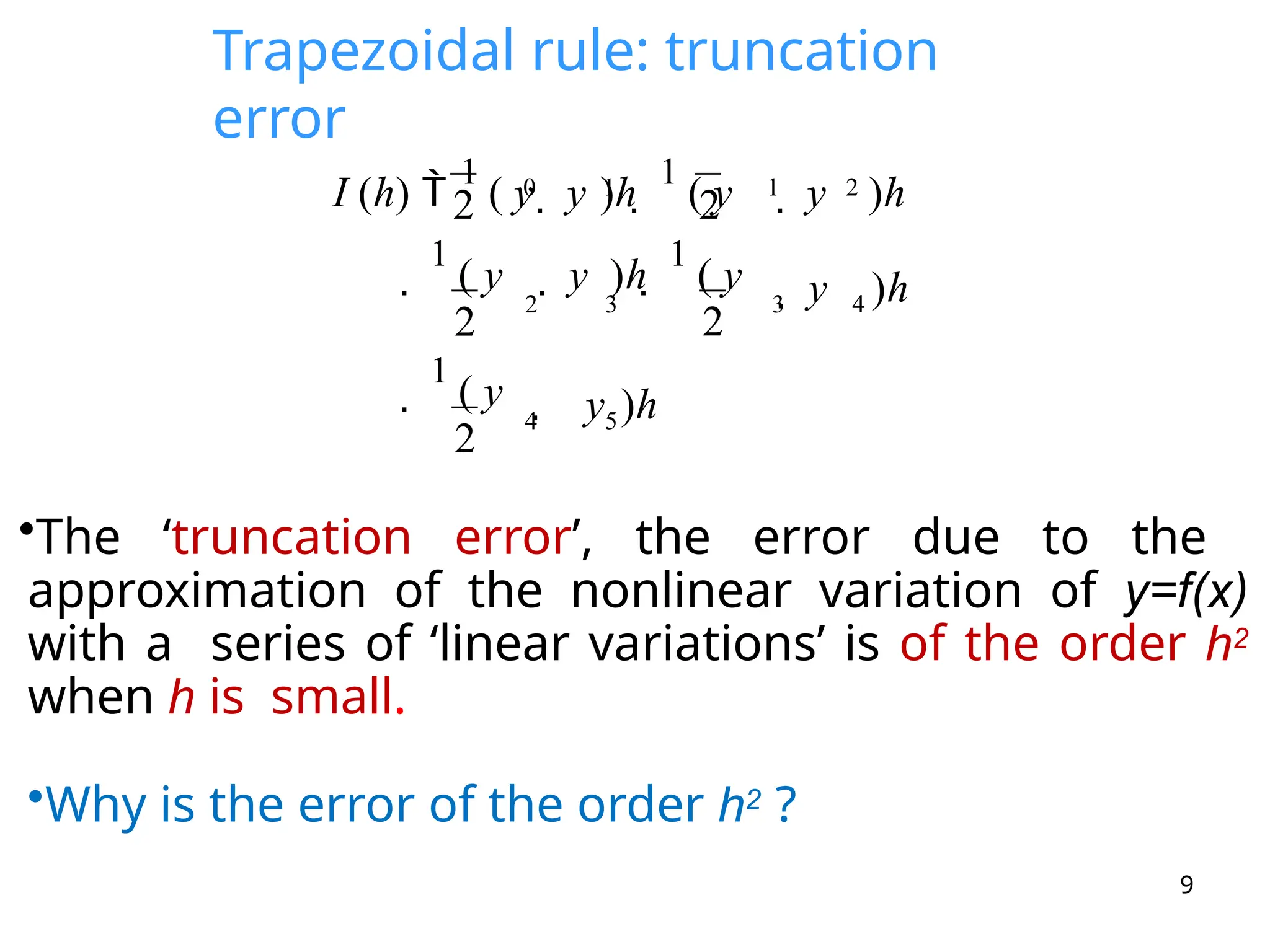

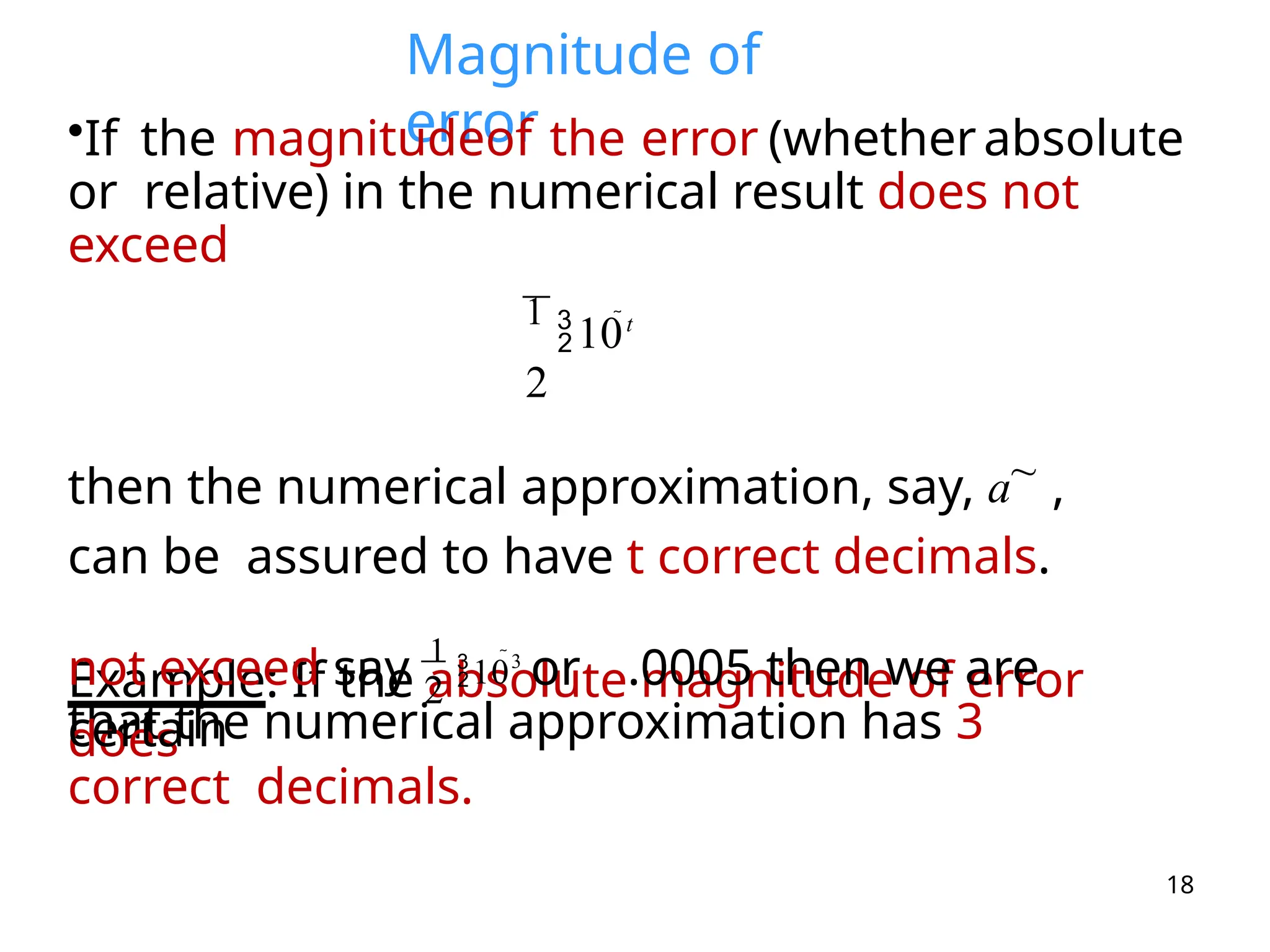

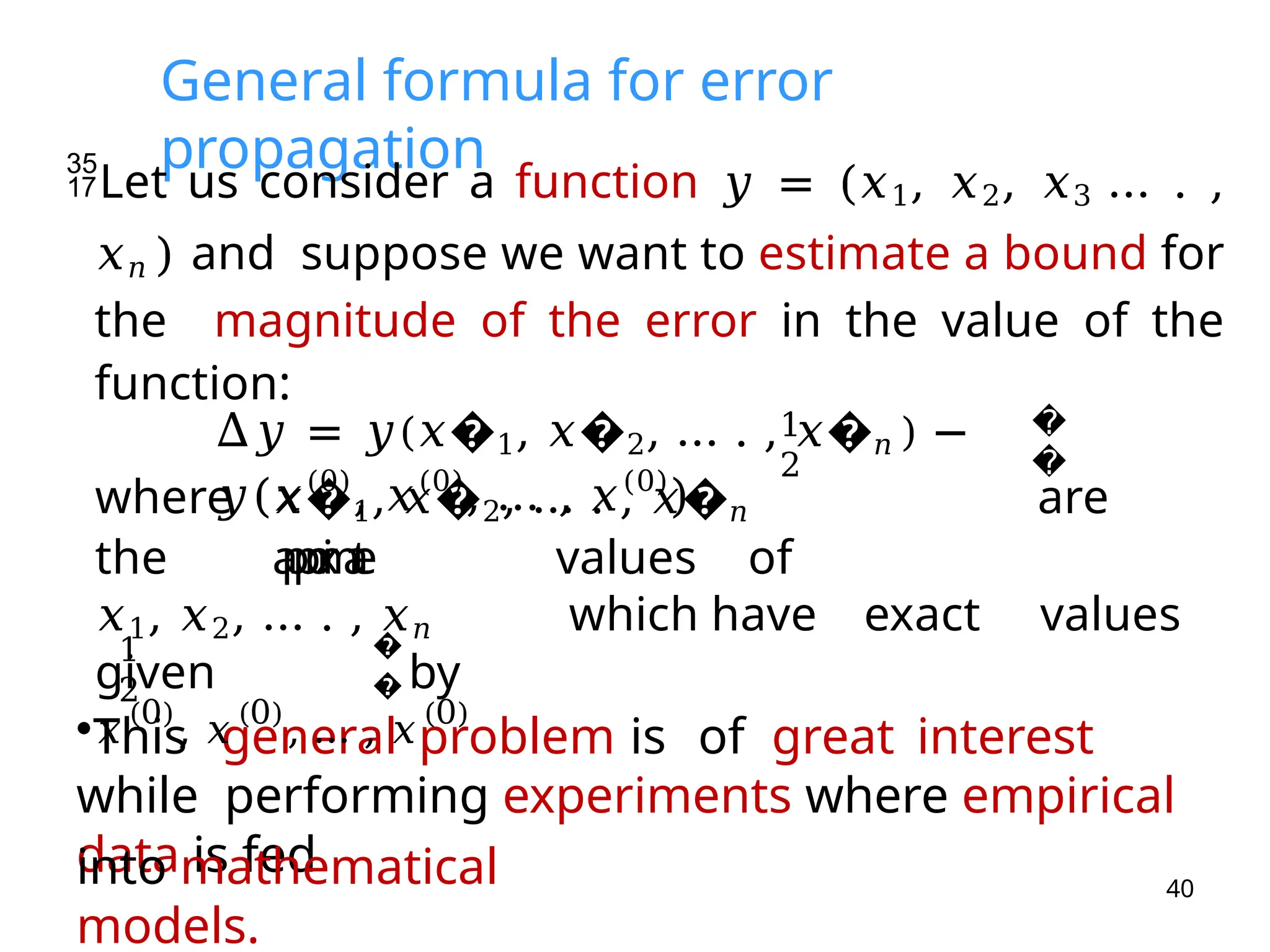

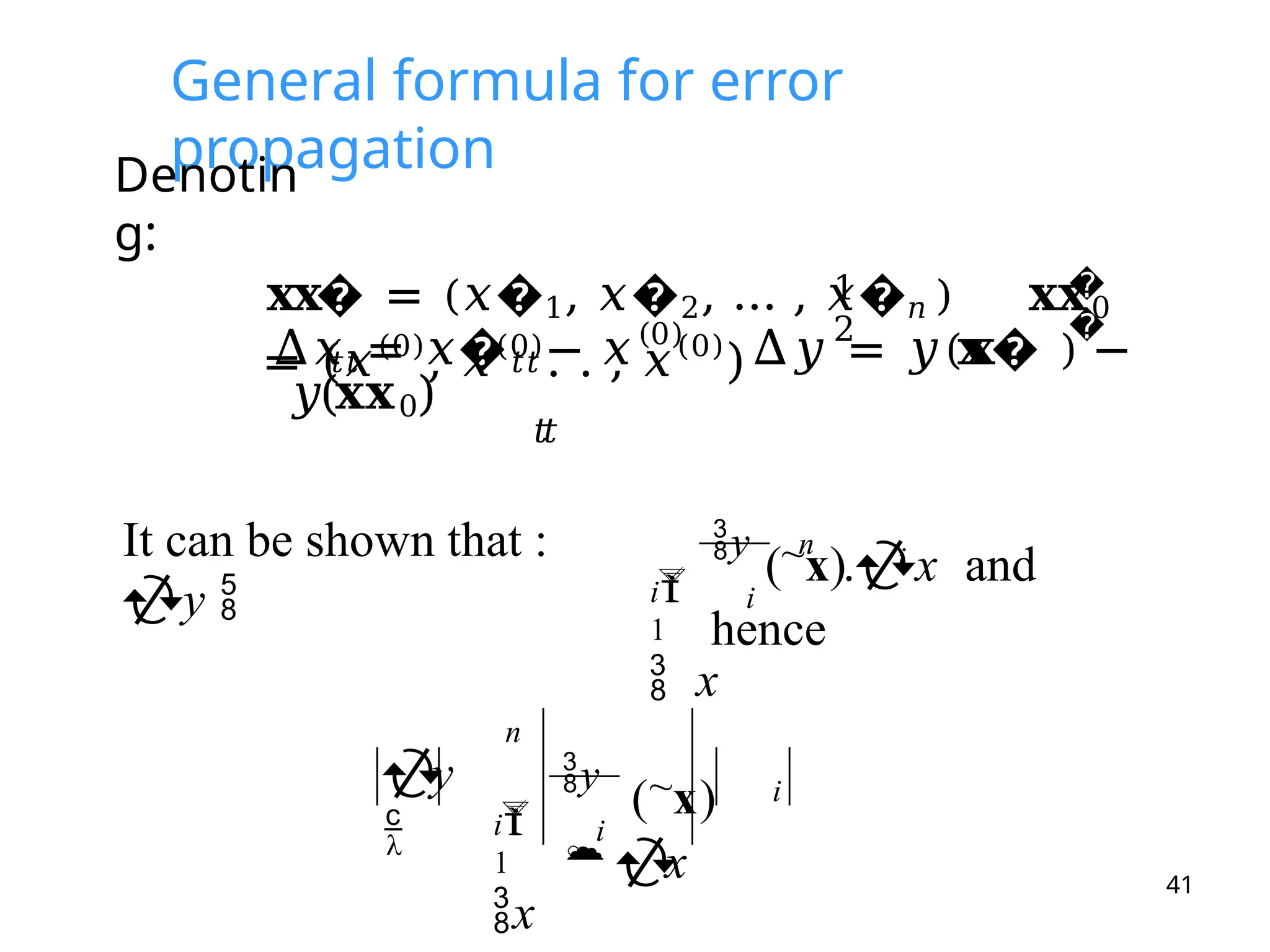

The document discusses error analysis in numerical calculations, focusing on round-off errors and truncation errors that can accumulate and lead to inaccurate results. It explains how the finite precision of computing devices can affect calculations and presents methods to reduce these errors, such as using higher-order polynomial approximations and Richardson's extrapolation. Additionally, it defines absolute and relative errors, as well as error bounds for operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division.

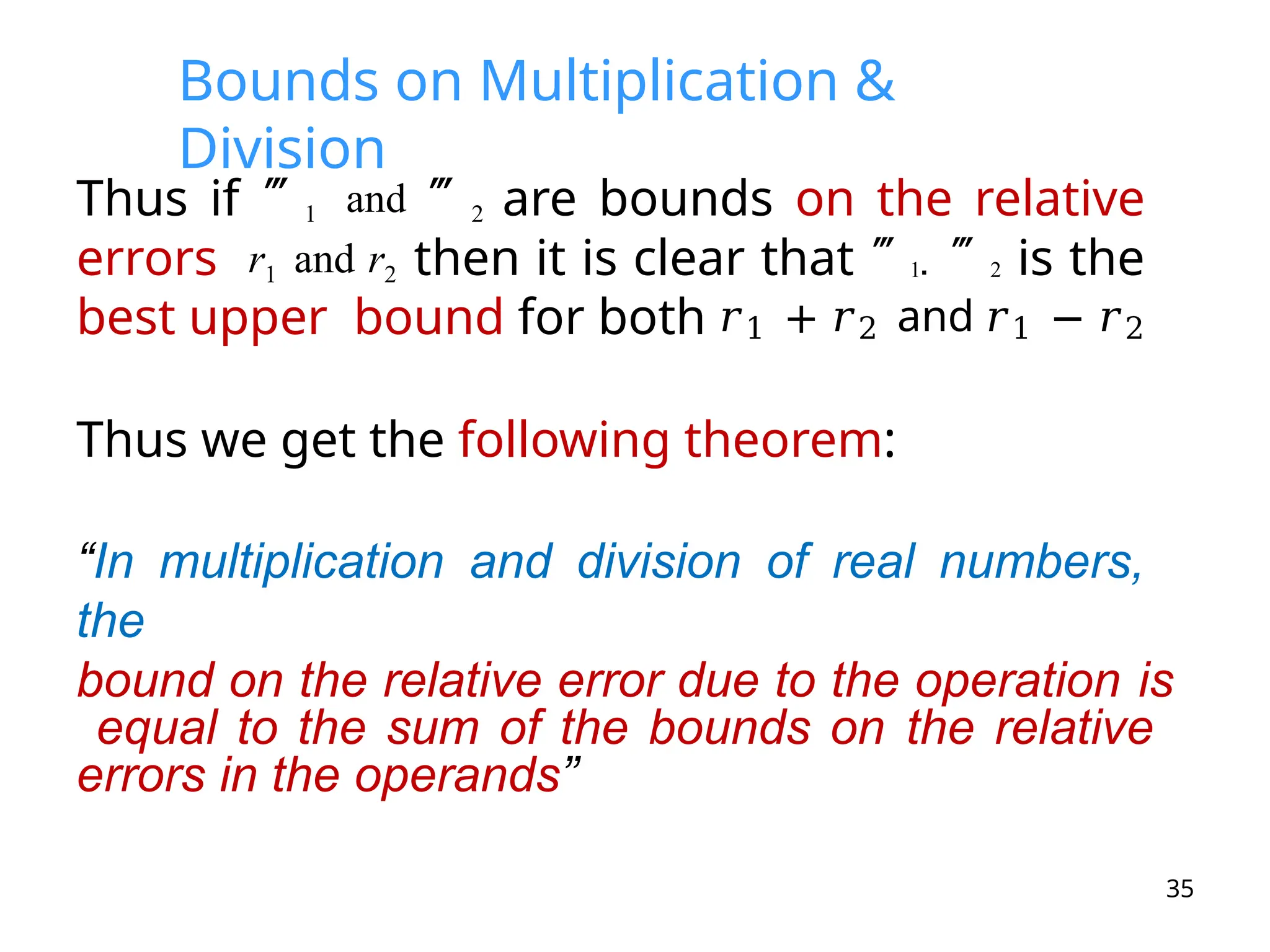

![General formula for error

propagation

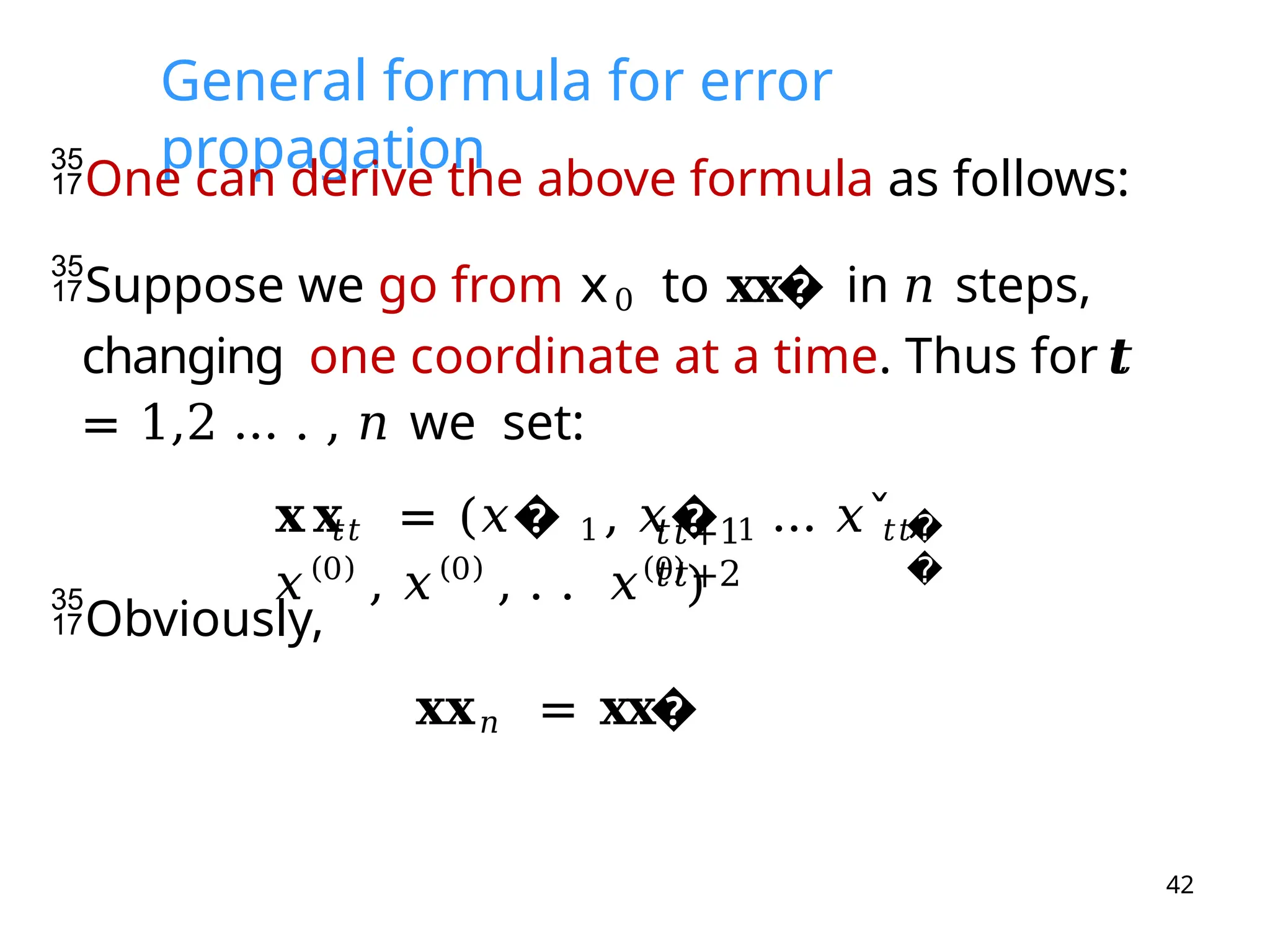

coordinate is changed

from

while the

rest

of the coordinates are left unchanged.

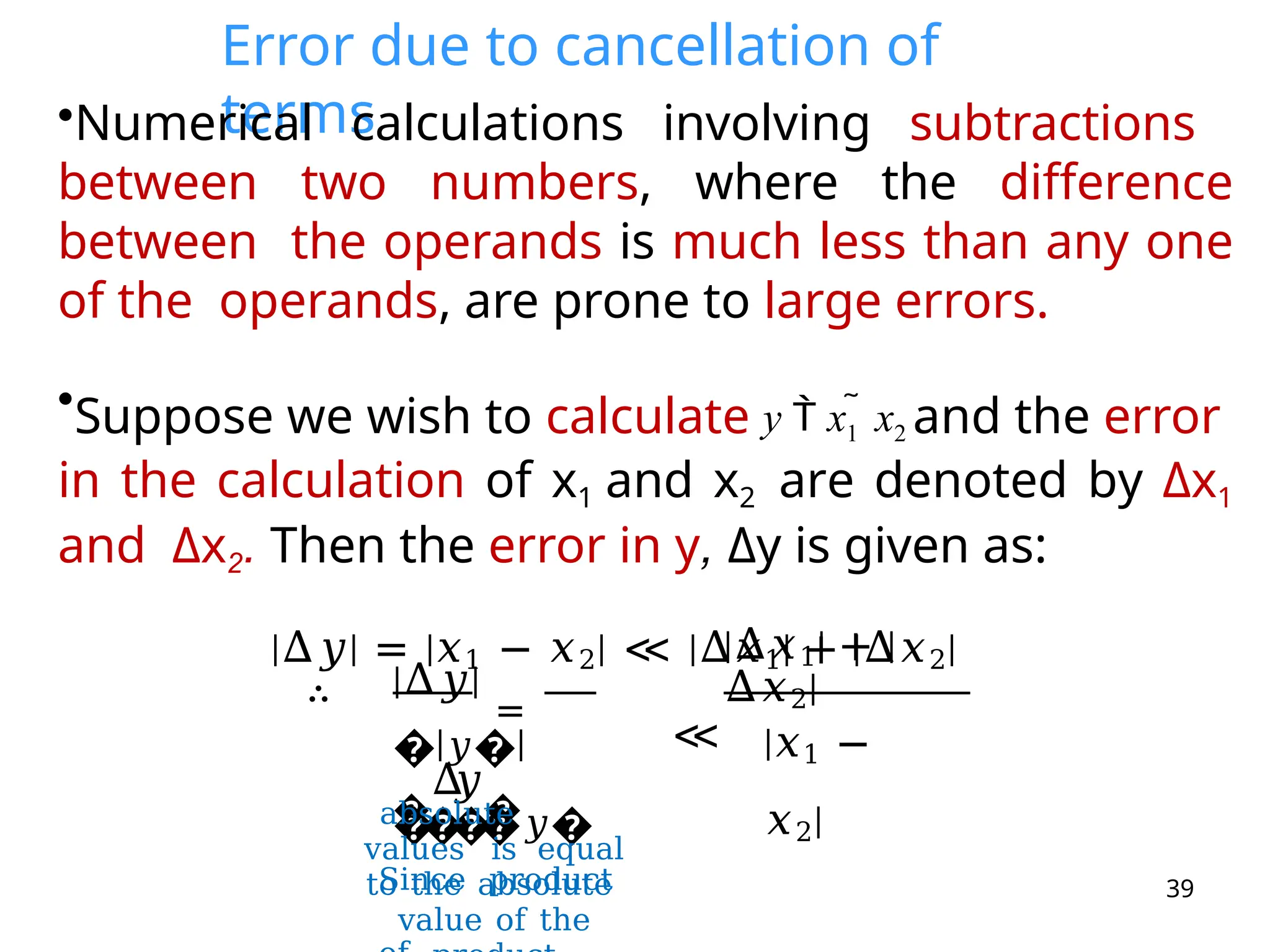

•Then by the mean value theorem, there

exists a

a such

that:

i i

x ~

to x

(0)

ξi xi1, xi

•In going from the (i 1)th

step to the ith

step, the

ith

43

𝑦(𝗑𝑡𝑡 ) − 𝑦(𝗑𝑡𝑡−1

=

𝜕

𝜕

𝑦

𝜕𝜕

𝑥𝑡

𝑡

) ( )

𝑡

𝑡

𝑡

𝑡

𝛏

𝛏. 𝑥

˜

�

− 𝑥

𝑡

�

�

(0

) �

�

�

𝑡𝑡+1

𝑡

𝑡

𝛏𝛏𝑡

𝑡 = 𝑥˜

� 1, … . 𝑥˜𝑡𝑡−1, 𝜉𝜉, 𝑥(0)

, …

𝑥(0)

� , 𝜉

𝜉 ∈ [𝑥(0)

, 𝑥˜𝑡

𝑡 ]

𝜕

𝜕

𝑥𝑡

𝑡

Hence one can write: 𝑦(𝗑𝑡𝑡 ) − 𝑦(𝗑𝑡𝑡−1) = 𝜕

𝜕

𝑦

(𝐱𝐱˜).

∆𝑥𝑡𝑡

(∗)

where the partial derivative of 𝑦 with respect to 𝑥𝑡

𝑡

at 𝛏𝛏𝑡

𝑡

is approximated by the partial derivative at the end

steps i.e.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture2-erroranalysis-241113182227-94d0e1d6/75/Lecture-2-Error-Analysis-Numerical-Analysis-43-2048.jpg)