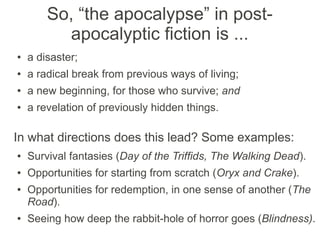

The document discusses themes of apocalypse and post-apocalyptic fiction, emphasizing the genre's role in revealing precarious social structures and truths previously hidden. It explores the cultural origins and significance of zombies as symbols of alienation and the human condition, drawing on concepts from various literary and philosophical sources. The text highlights the intersection of horror and societal critique, illustrating how these narratives reflect our anxieties about identity and existence within the global economy.

![So what is a “revelation”?

‘To veil’ comes from ME veilen, from the ME n veile,

whence the English noun veil: and ME veile is adopted

from Old N. French, which, like Old French-French voile,

derives from Medieval-Vulgar Latin vēla, from Latin uēla,

plural of uēlum, “a sail,” but also “[a piece of] drapery, an

awning”; originally from Indo-European *wegslom, from

*weg-, “to weave.”

Latin uēlāre has prefix-compound reuēlāre, “to pull back

the curtain, or covering, from,” hence “to disclose”: whence

Old French-Middle French reveler, whence “to reveal.”

Derivative Late Latin reuēlātiō, “an uncovering, hence of a

secret.”

(Adapted from Eric Partridge’s Origins: An

Etymological Dictionary of Modern English)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture03-theendandafterwards-130211024514-phpapp01/85/Lecture-03-The-End-and-Afterwards-4-320.jpg)

![We’ll talk more about horror on

Wednesday, but a few words now …

Tragedy is “an imitation of a noble and

complete action, having the proper magnitude;

it employs language that has been artistically

enhanced […] it is presented in dramatic, not

narrative form, and achieves, through the

representation of pitiable and fearful incidents,

the catharsis of such pitiable and fearful

incidents.”

“tragedy is not an imitation of men, per se, but

of human action and life and happiness and

misery.”

– Aristotle, Poetics (ca. 330 BCE)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture03-theendandafterwards-130211024514-phpapp01/85/Lecture-03-The-End-and-Afterwards-7-320.jpg)

![“Horror, in this way, shows us our inherent

skepticism about absolute progress. […]

Dracula, The Call of Cthulu, or The Island of Dr.

Moreau present a dark-regressive shadow

image of the bright and progressive veneer of

eighteenth- and nineteenth-century optimism.

The origins of modern horror provide a vivid

presentation of the inherent moral weaknesses

and often-present darkness in the human

imagination.”

– Philip Tallon, “Through a Mirror, Darkly” (2010)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture03-theendandafterwards-130211024514-phpapp01/85/Lecture-03-The-End-and-Afterwards-8-320.jpg)

![What about the undead, then?

“Horror arises not because Dracula destroys

bodies, but because he appropriates and

transforms them. Having yielded to his assault,

one literally ‘goes native’ by becoming a

vampire oneself. [Dracula’s victims] receive a

new racial identity, one that marks them as

literally ‘Other.’ Miscegenation leads, not to the

mixing of races, but to the biological and

political annihilation of the weaker race by the

stronger.”

– Stephen Arata, “The Occidental Tourist” (1990)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture03-theendandafterwards-130211024514-phpapp01/85/Lecture-03-The-End-and-Afterwards-9-320.jpg)