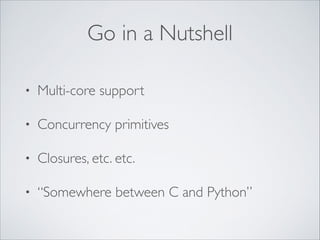

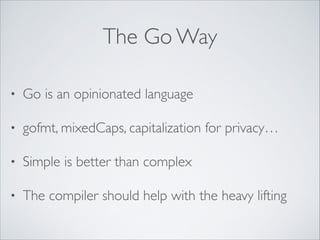

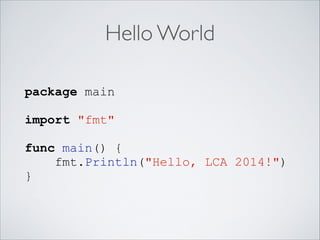

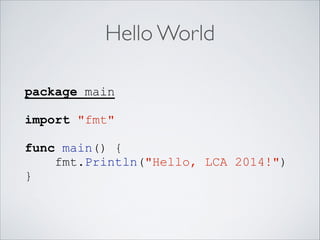

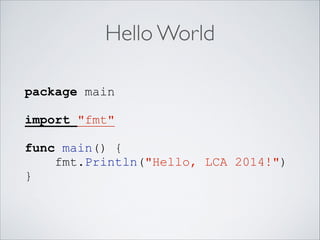

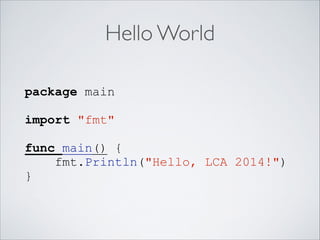

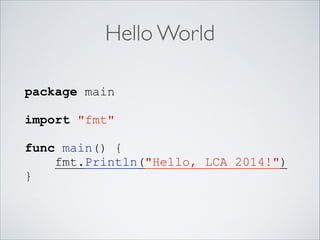

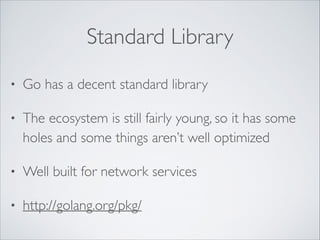

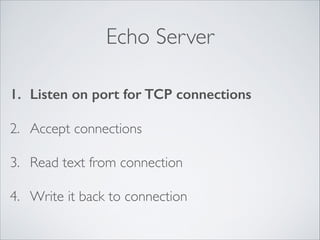

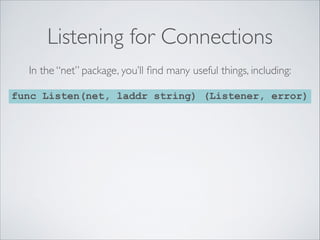

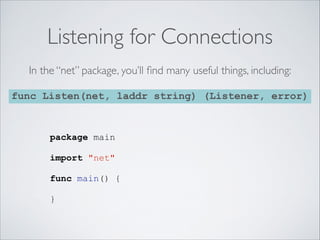

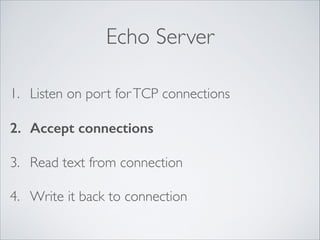

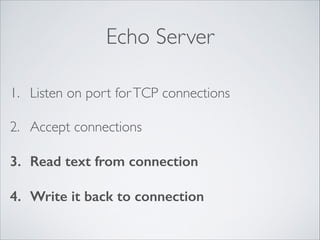

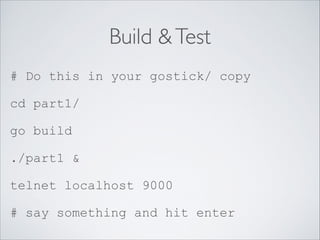

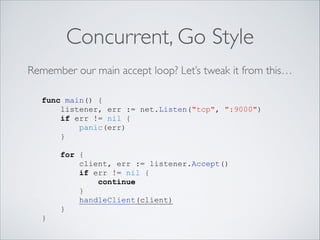

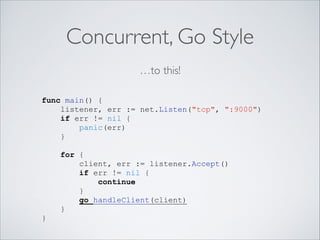

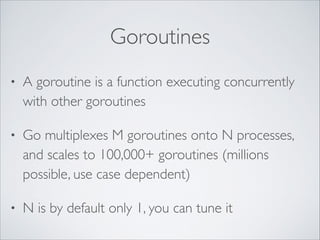

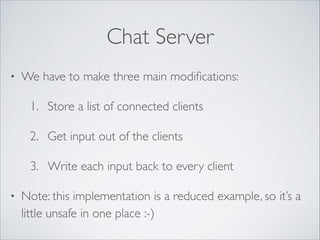

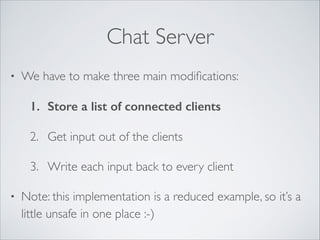

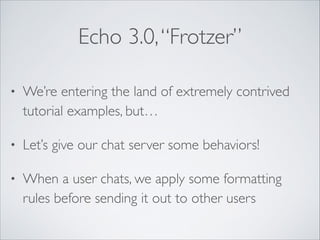

The document serves as a tutorial for developers to get started with the Go programming language, emphasizing its design for building systems, static typing, garbage collection, and built-in concurrency. It includes a step-by-step guide to creating network services such as an echo server and a chat server, illustrating concepts like goroutines and channels for concurrent programming. The tutorial also covers basic programming constructs in Go and practical coding examples for building applications.

![Client Handler

func Read(b []byte) (int, error)

func handleClient(client net.Conn) {

for {

// read from our client

// write it back to our client

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-32-320.jpg)

![Client Handler

func Read(b []byte) (int, error)

func handleClient(client net.Conn) {

for {

// read from our client

// write it back to our client

}

}

Okay, so what’s a []byte?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-33-320.jpg)

![So, []byte…

•

Let’s make an array of bytes:

var ary [4096]byte

•

What if we don’t know the size? Or don’t care?

Slices solve this problem:

var aryslice []byte

•

This is great, but what is it?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-36-320.jpg)

![Slices Explained

var a [16]byte is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-37-320.jpg)

![Slices Explained

var a [16]byte is

a[3] is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-38-320.jpg)

![Slices Explained

var a [16]byte is

a[3] is

a[6:8] is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-39-320.jpg)

![Slices Explained

var a [16]byte is

a[3] is

a[6:8] is

var s []byte is nothing to start with.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-40-320.jpg)

![Slices Explained

var a [16]byte is

a[3] is

a[6:8] is

var s []byte is nothing to start with.

s = a[6:8]; s is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-41-320.jpg)

![Slices Explained

var a [16]byte is

a[3] is

a[6:8] is

var s []byte is nothing to start with.

s = a[6:8]; s is

s[0] is the same as a[6], etc!

A slice is simply a window into a backing array.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-42-320.jpg)

![Client Handler

func Read(b []byte) (int, error)

func handleClient(client net.Conn) {

for {

!

!

!

!

!

!

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-45-320.jpg)

![Client Handler

func Read(b []byte) (int, error)

func handleClient(client net.Conn) {

for {

buf := make([]byte, 4096)

!

!

!

!

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-46-320.jpg)

![Client Handler

func Read(b []byte) (int, error)

func handleClient(client net.Conn) {

for {

buf := make([]byte, 4096)

numbytes, err := client.Read(buf)

!

!

!

!

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-47-320.jpg)

![Client Handler

func Read(b []byte) (int, error)

func handleClient(client net.Conn) {

for {

buf := make([]byte, 4096)

numbytes, err := client.Read(buf)

if numbytes == 0 || err != nil {

return

}

!

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-48-320.jpg)

![Client Handler

func Read(b []byte) (int, error)

func handleClient(client net.Conn) {

for {

buf := make([]byte, 4096)

numbytes, err := client.Read(buf)

if numbytes == 0 || err != nil {

return

}

client.Write(buf)

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-49-320.jpg)

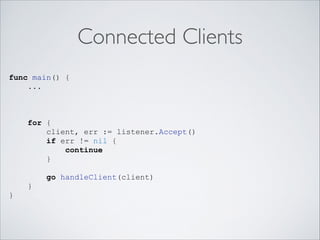

![Connected Clients

func main() {

...

!

var clients []net.Conn

!

for {

client, err := listener.Accept()

if err != nil {

continue

}

clients = append(clients, client)

go handleClient(client)

}

}

Build a slice of clients

and then append

each new client to

the slice.

!

The append built-in

handles automatically

allocating and

growing the backing

array as necessary.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-64-320.jpg)

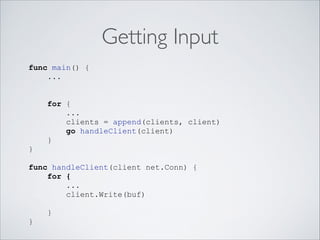

![Getting Input

func main() {

...

input := make(chan []byte, 10)

!

for {

...

clients = append(clients, client)

go handleClient(client)

}

}

!

func handleClient(client net.Conn) {

for {

...

client.Write(buf)

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-67-320.jpg)

![Getting Input

func main() {

...

input := make(chan []byte, 10)

!

for {

...

clients = append(clients, client)

go handleClient(client, input)

}

}

!

func handleClient(client net.Conn) {

for {

...

client.Write(buf)

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-68-320.jpg)

![Getting Input

func main() {

...

input := make(chan []byte, 10)

!

for {

...

clients = append(clients, client)

go handleClient(client, input)

}

}

!

func handleClient(client net.Conn, input chan []byte) {

for {

...

client.Write(buf)

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-69-320.jpg)

![Getting Input

func main() {

...

input := make(chan []byte, 10)

!

for {

...

clients = append(clients, client)

go handleClient(client, input)

}

}

!

func handleClient(client net.Conn, input chan []byte) {

for {

...

client.Write(buf)

input <- buf

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-70-320.jpg)

![Getting Input

func main() {

...

input := make(chan []byte, 10)

!

for {

...

clients = append(clients, client)

go handleClient(client, input)

}

}

!

func handleClient(client net.Conn, input chan []byte) {

for {

...

client.Write(buf)

Removed the Write!

input <- buf

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-71-320.jpg)

![The Chat Manager

func main() {

...

var clients []net.Conn

input := make(chan []byte, 10)

!

!

!

!

We’ve

!

!

!

!

...

}

seen this all before…](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-74-320.jpg)

![The Chat Manager

func main() {

...

var clients []net.Conn

input := make(chan []byte, 10)

go func() {

!

!

!

!

!

}()

...

}

You can create goroutines

out of closures, too.

!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-75-320.jpg)

![The Chat Manager

!

func main() {

...

var clients []net.Conn

input := make(chan []byte, 10)

go func() {

for {

message := <-input

!

!

}

}()

...

}

!

!

This is all blocking!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-76-320.jpg)

![The Chat Manager

!

func main() {

...

var clients []net.Conn

This

input := make(chan []byte, 10)

go func() {

for {

message := <-input

for _, client := range clients {

!

}

}

}()

...

}

!

!

is all blocking!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-77-320.jpg)

![The Chat Manager

func main() {

...

var clients []net.Conn

input := make(chan []byte, 10)

go func() {

for {

message := <-input

for _, client := range clients {

client.Write(message)

}

}

}()

...

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-79-320.jpg)

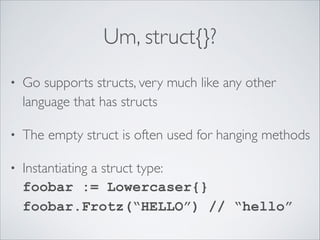

![But First: More Type Talk!

•

Go doesn’t have classes (or objects, really)

•

However, you have named types, and methods are

attached to named types:

type Uppercaser struct{}

!

func (self Uppercaser) Frotz(input []byte) []byte {

return bytes.ToUpper(input)

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-82-320.jpg)

![Interfaces

•

In Go, an interface specifies a collection of

methods attached to a name

•

Interfaces are implicit (duck typed)

type Frotzer interface {

Frotz([]byte) []byte

}

!

type Uppercaser struct{}

func (self Uppercaser) Frotz(input []byte) []byte {

return bytes.ToUpper(input)

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-84-320.jpg)

![Implementing Frotzing

func chatManager(clients *[]net.Conn, input chan []byte

) {

for {

message := <-input

for _, client := range *clients {

client.Write(message)

}

}

}

This is the input handler loop we built a few minutes ago,

except now we pulled it out of main and made it a

function.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-85-320.jpg)

![Implementing Frotzing

func chatManager(clients *[]net.Conn, input chan []byte,

frotz Frotzer) {

for {

message := <-input

for _, client := range *clients {

client.Write(frotz.Frotz(message))

}

}

}

Now it takes a third argument: an interface. Any type that

implements Frotzer can be used!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-86-320.jpg)

![Making Frotzers

These are both named types, and both implement

(implicitly!) the Frotzer interface. Thanks, compiler!

type Uppercaser struct{}

func (self Uppercaser) Frotz(input []byte) []byte {

return bytes.ToUpper(input)

}

!

type Lowercaser struct{}

func (self Lowercaser) Frotz(input []byte) []byte {

return bytes.ToLower(input)

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-87-320.jpg)

![A New Main

func main() {

...

var clients []net.Conn

input := make(chan []byte, 10)

go chatManager(&clients, input)

!

!

for {

client, err := listener.Accept()

if err != nil {

continue

}

clients = append(clients, client)

go handleClient(client, input)

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-88-320.jpg)

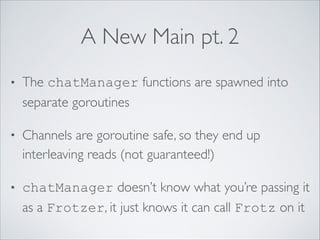

![A New Main

func main() {

...

var clients []net.Conn

input := make(chan []byte, 10)

go chatManager(&clients, input, Lowercaser{})

go chatManager(&clients, input, Uppercaser{})

!

for {

client, err := listener.Accept()

if err != nil {

continue

}

clients = append(clients, client)

go handleClient(client, input)

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lca2014-introductiontogo-140109035742-phpapp02/85/LCA2014-Introduction-to-Go-89-320.jpg)