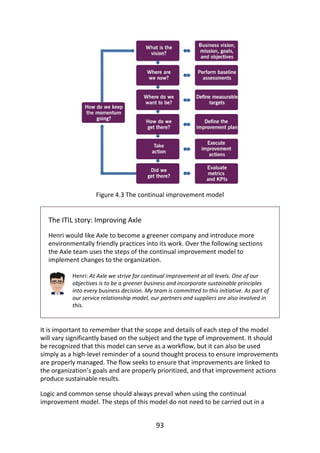

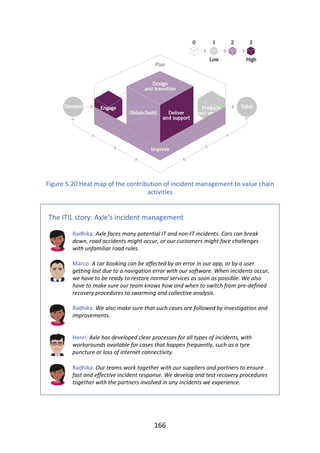

This document provides an overview of the ITIL Foundation publication. It introduces Axle Car Hire, a fictional company undergoing a digital transformation using ITIL best practices. The publication covers the key concepts of the ITIL service value system framework and management practices. It is intended to help readers understand ITIL 4 and support candidates studying for the ITIL Foundation exam.