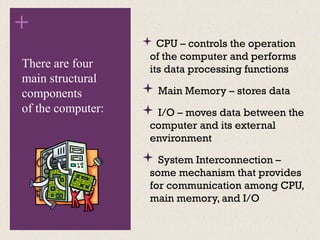

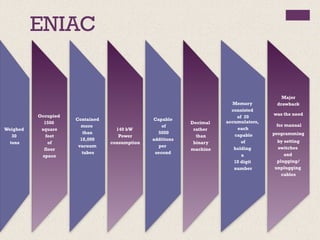

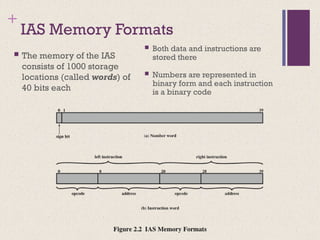

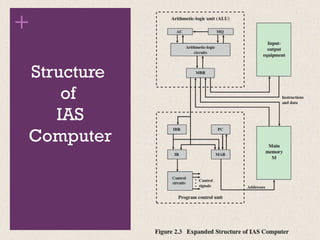

The document provides an overview of computer architecture, detailing the operational units, hierarchical structure, and primary functions such as data processing and movement. It discusses essential components, including the CPU, main memory, and I/O mechanisms, while tracing the evolution of computers from ENIAC to the early general-purpose machines like the IAS computer. Key concepts such as the stored program architecture proposed by John von Neumann are also highlighted.