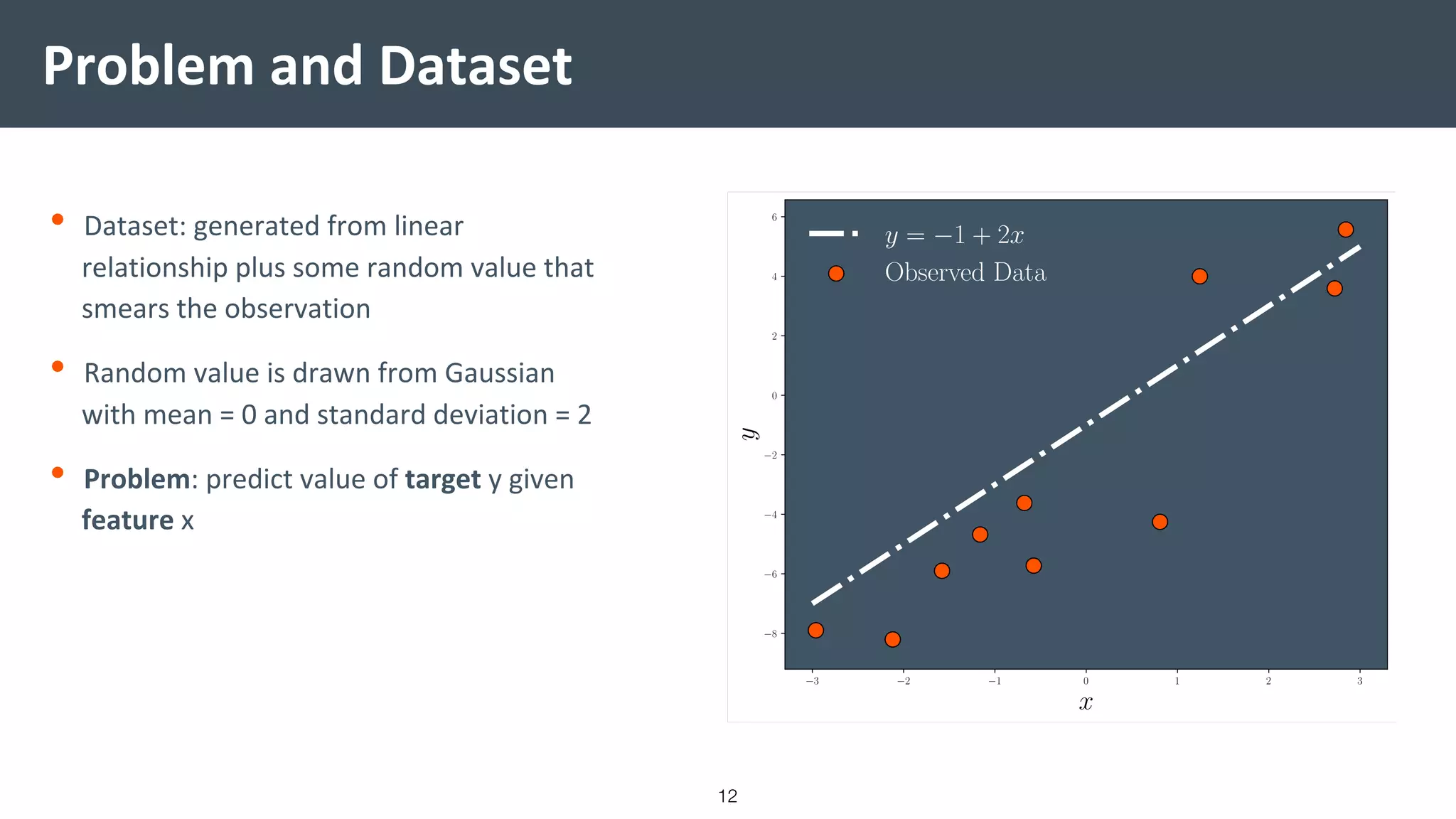

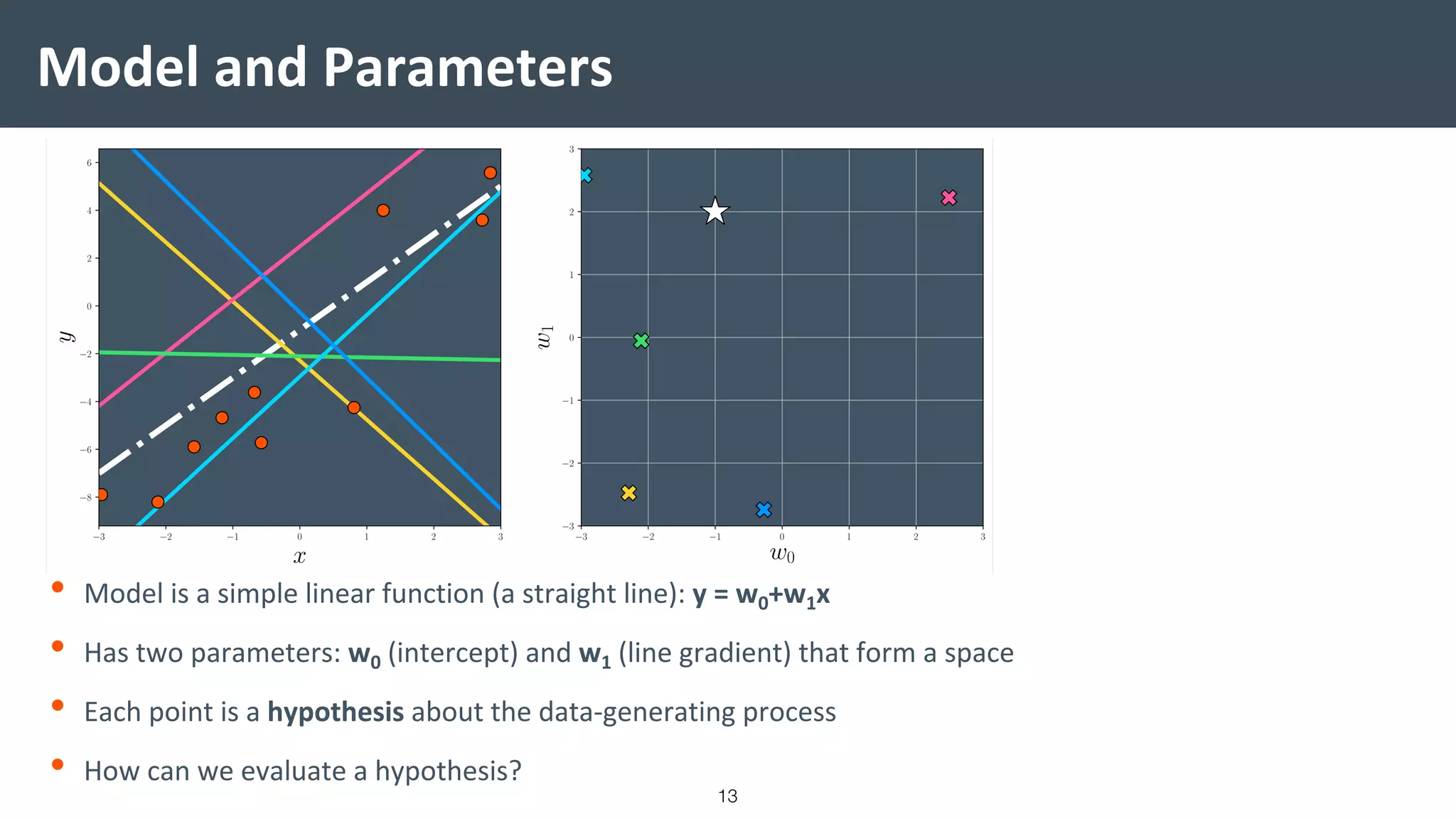

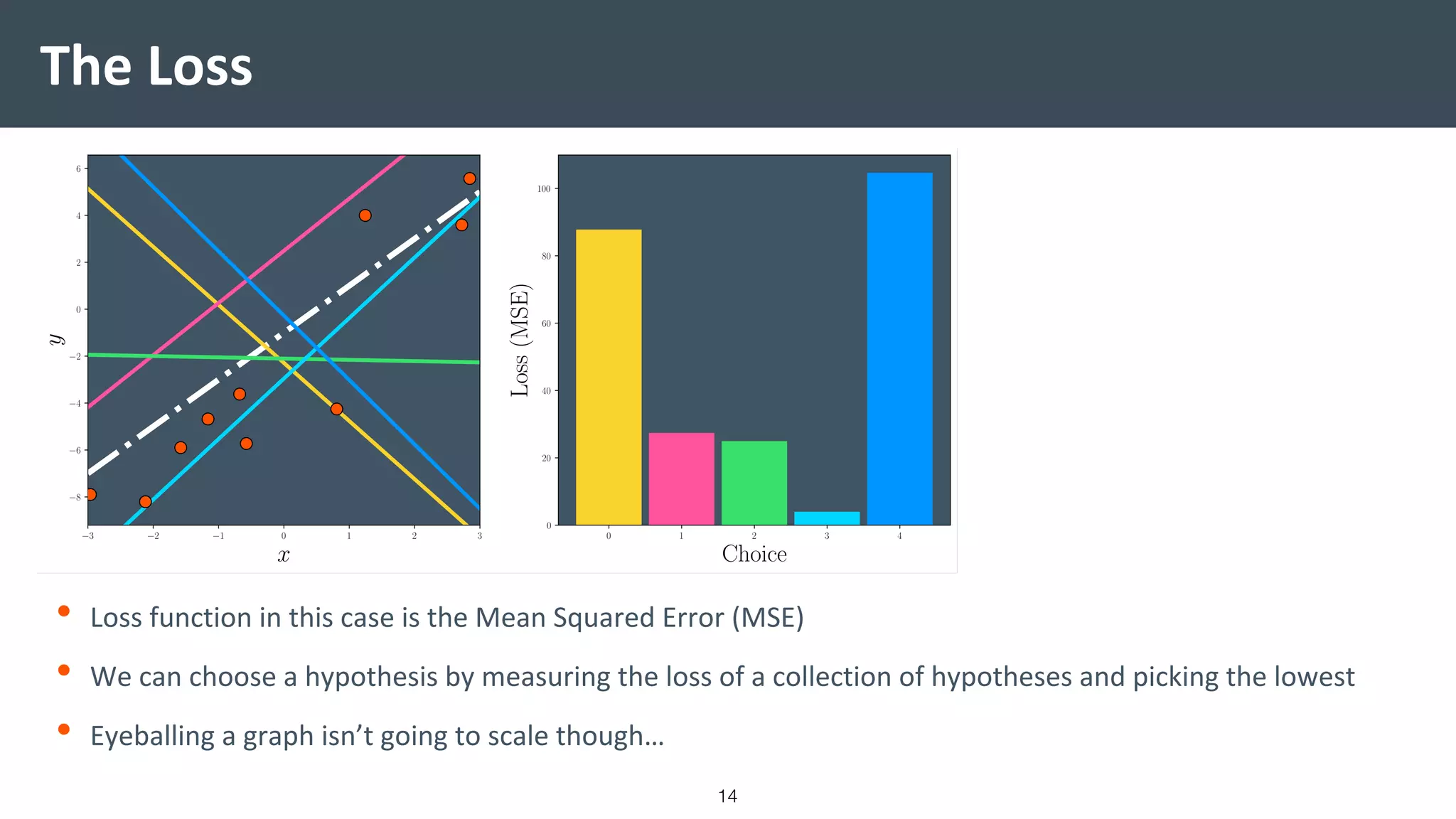

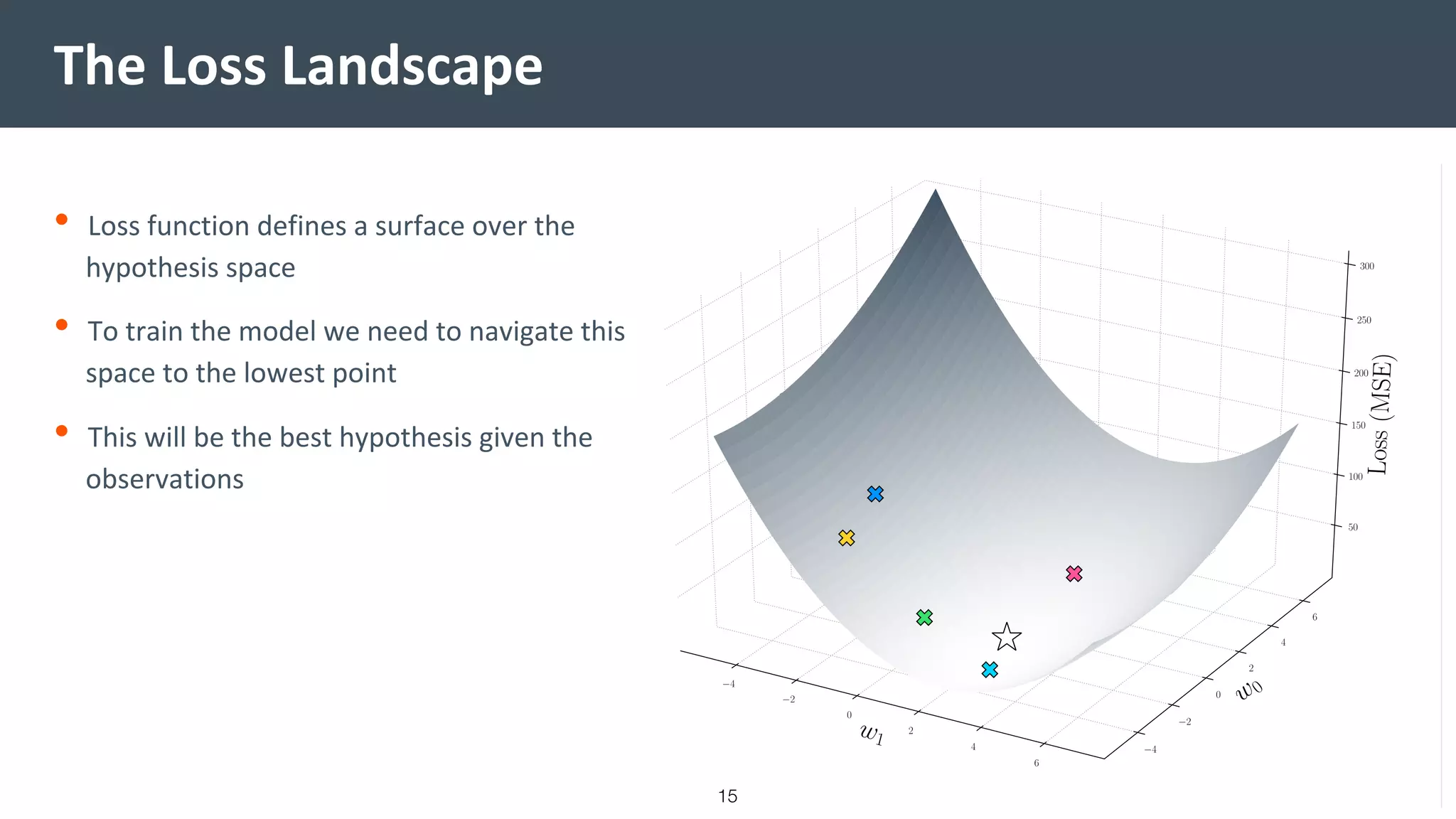

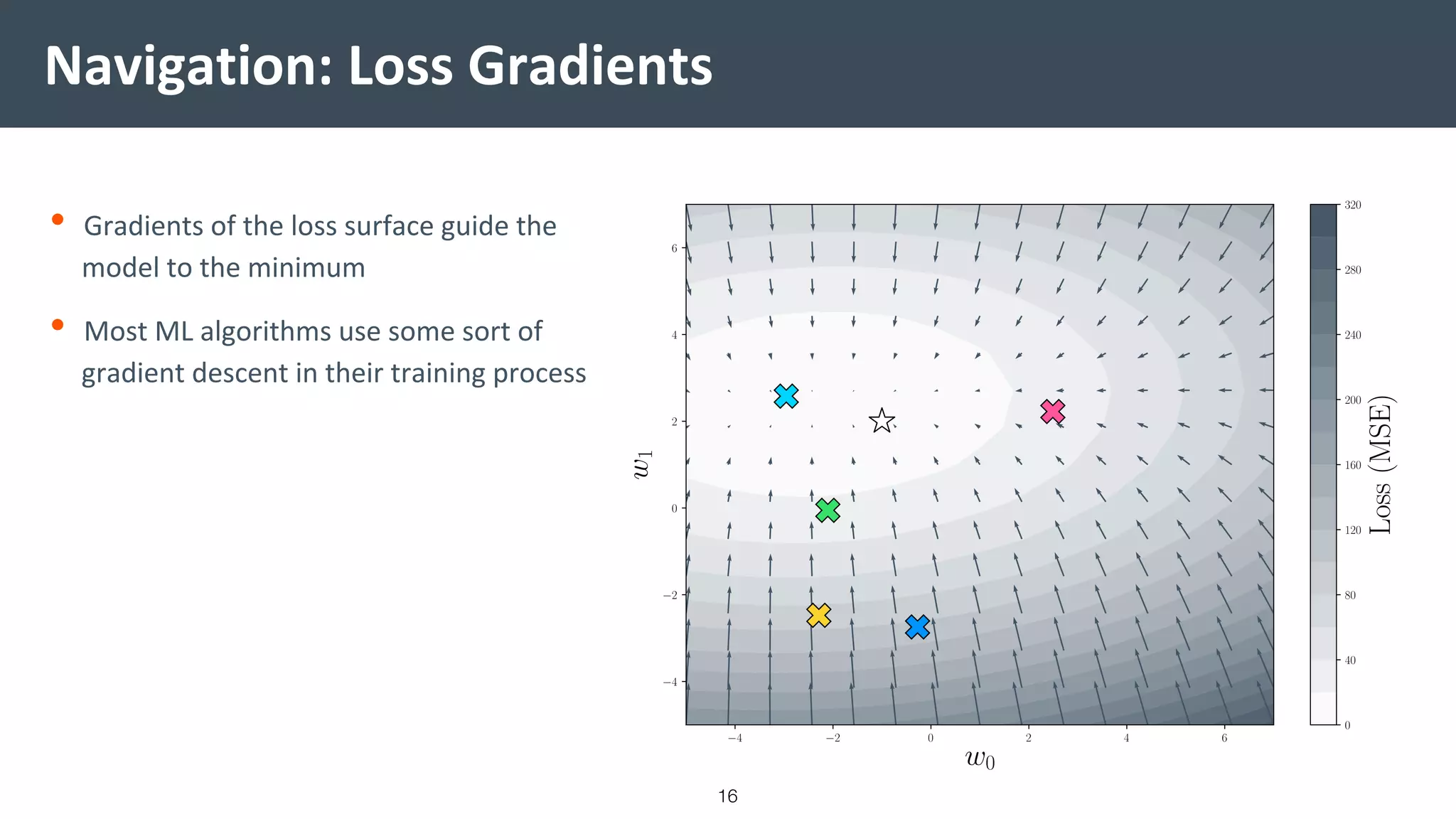

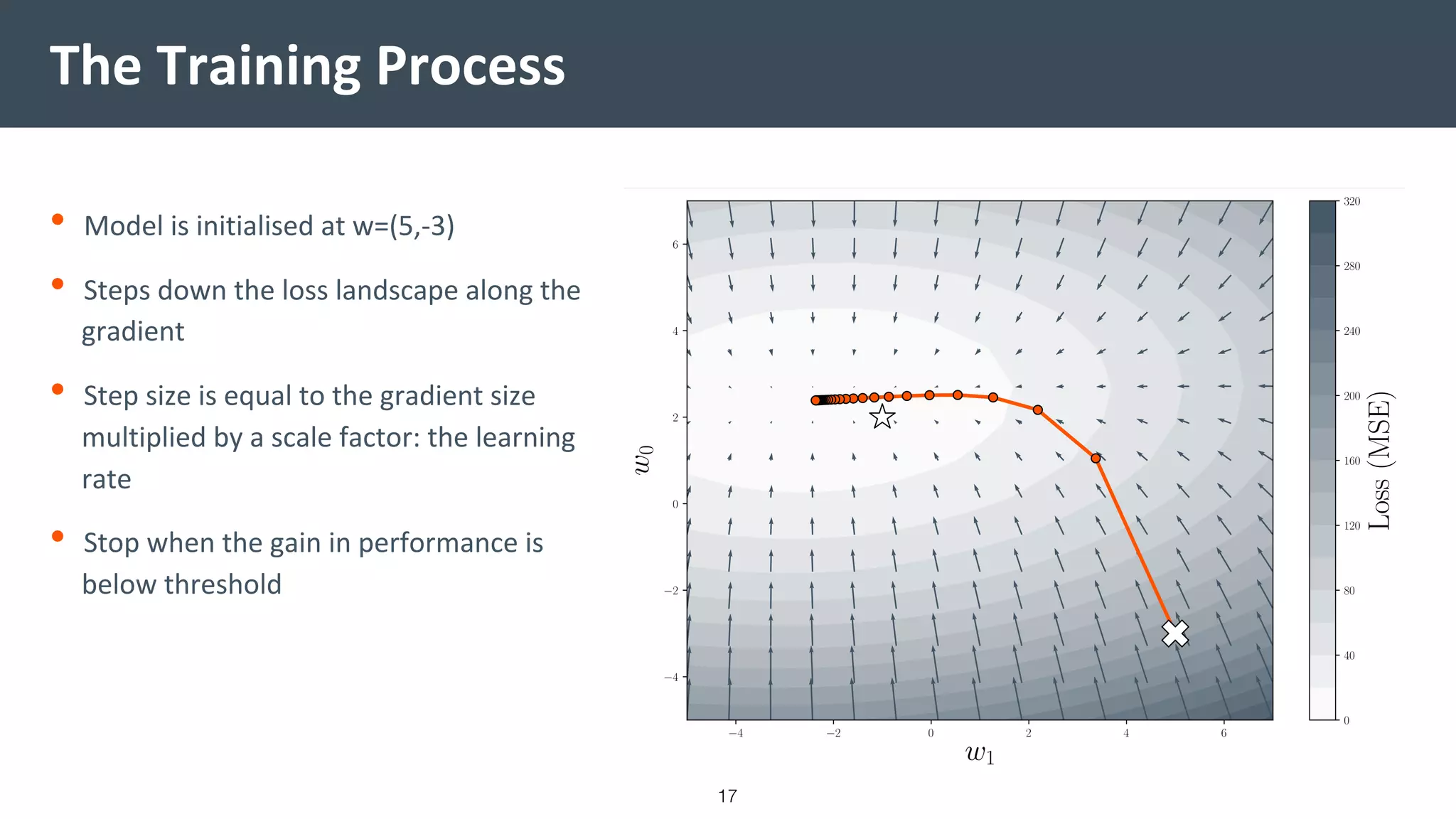

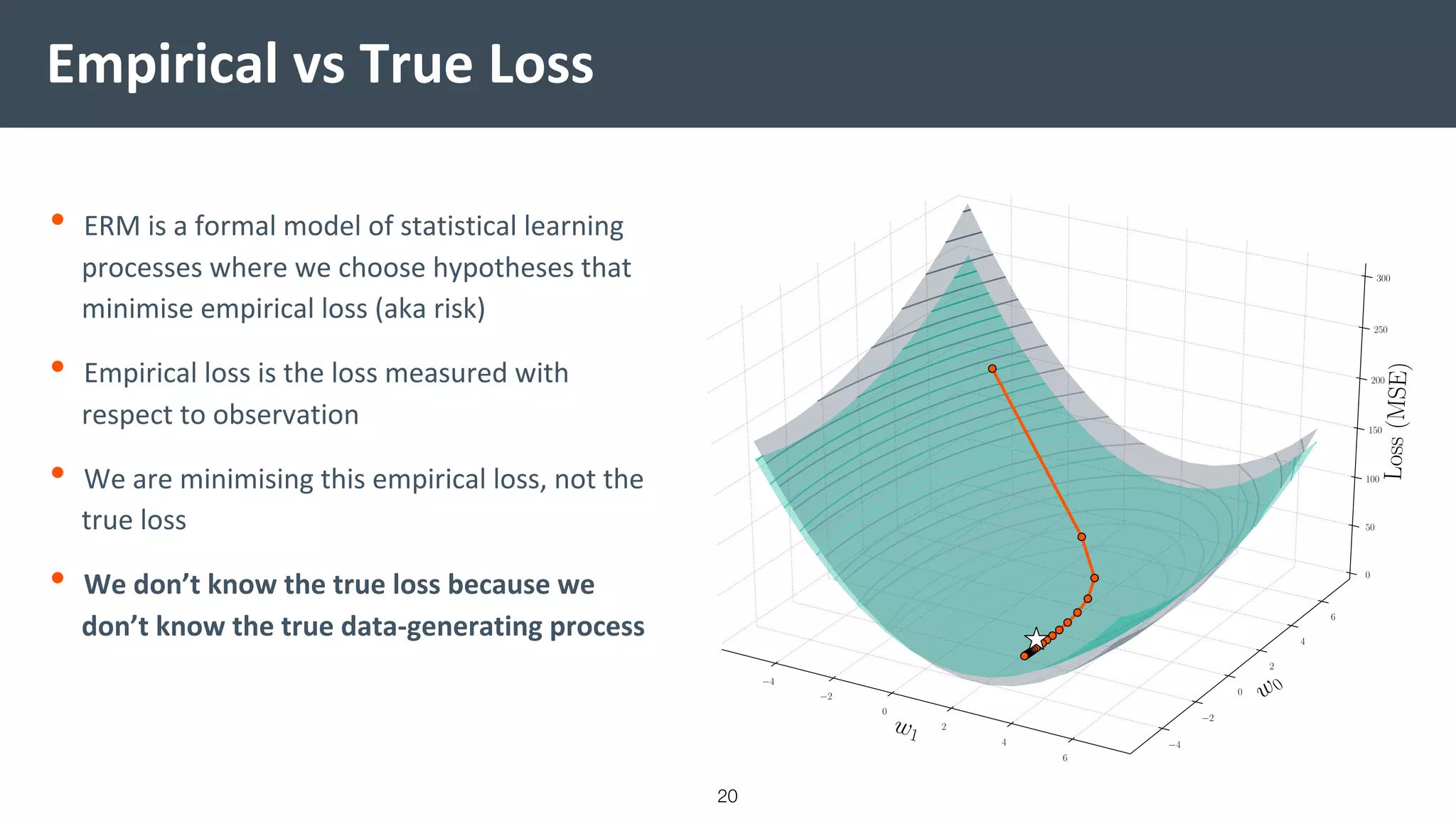

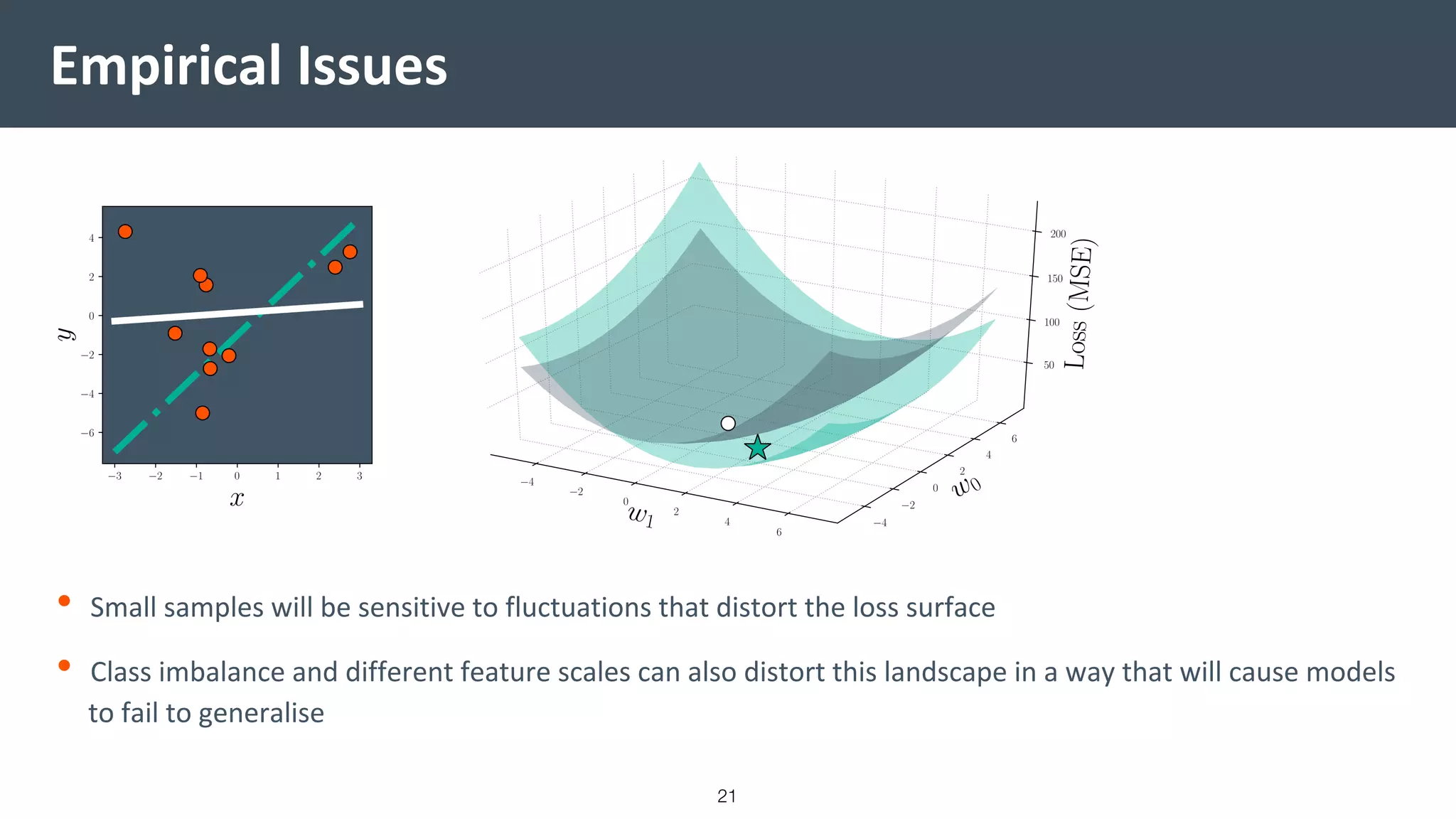

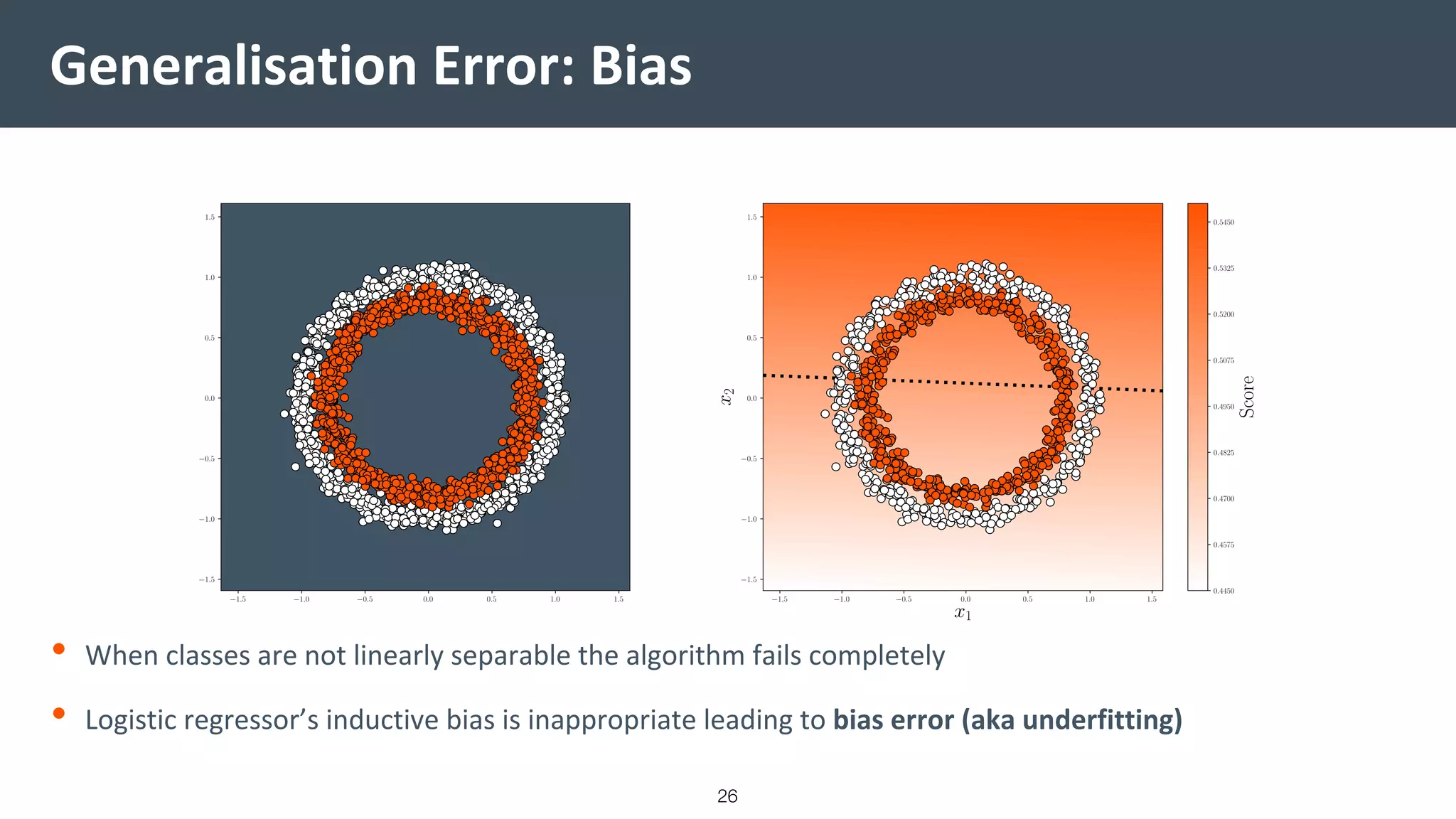

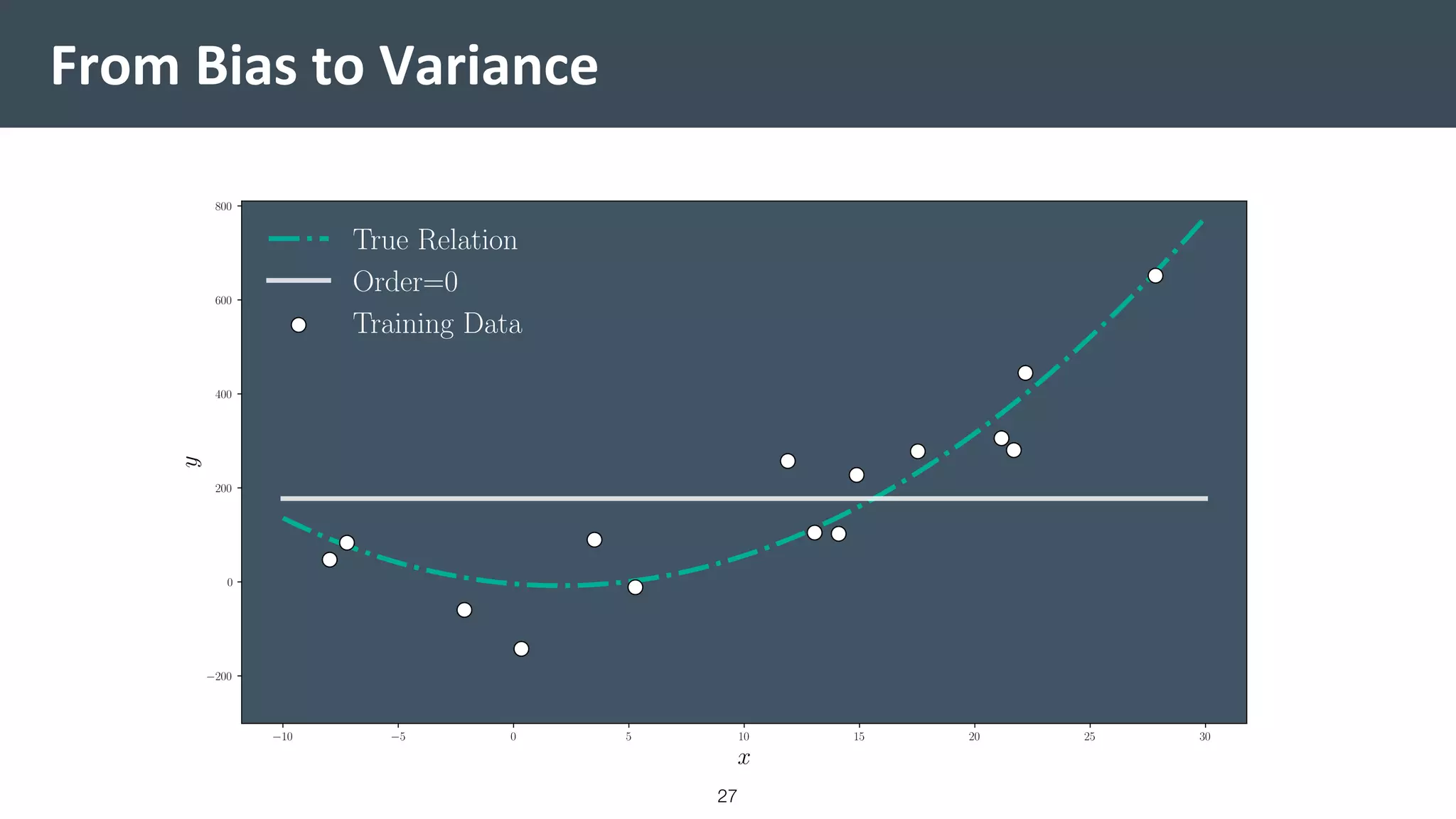

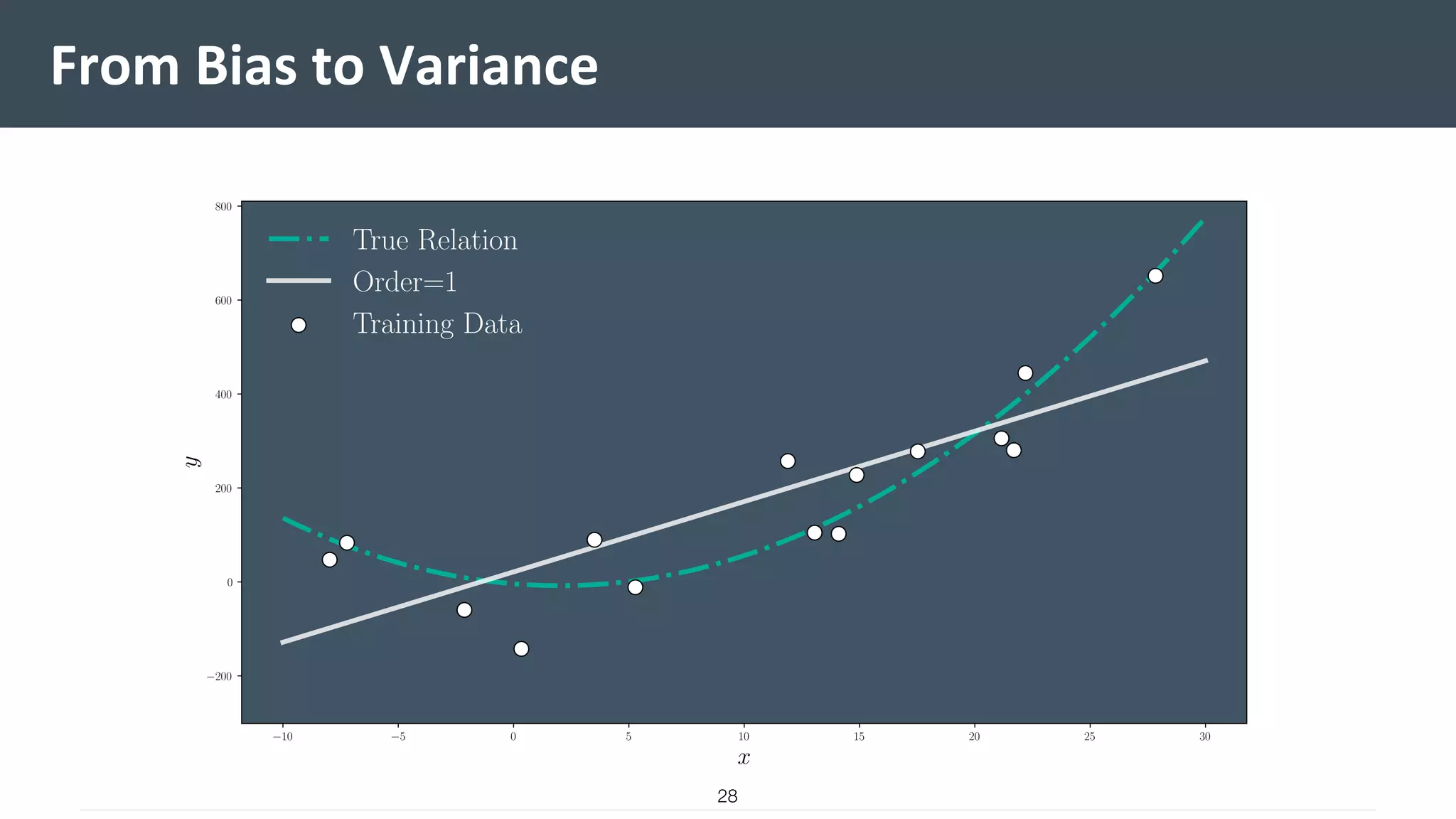

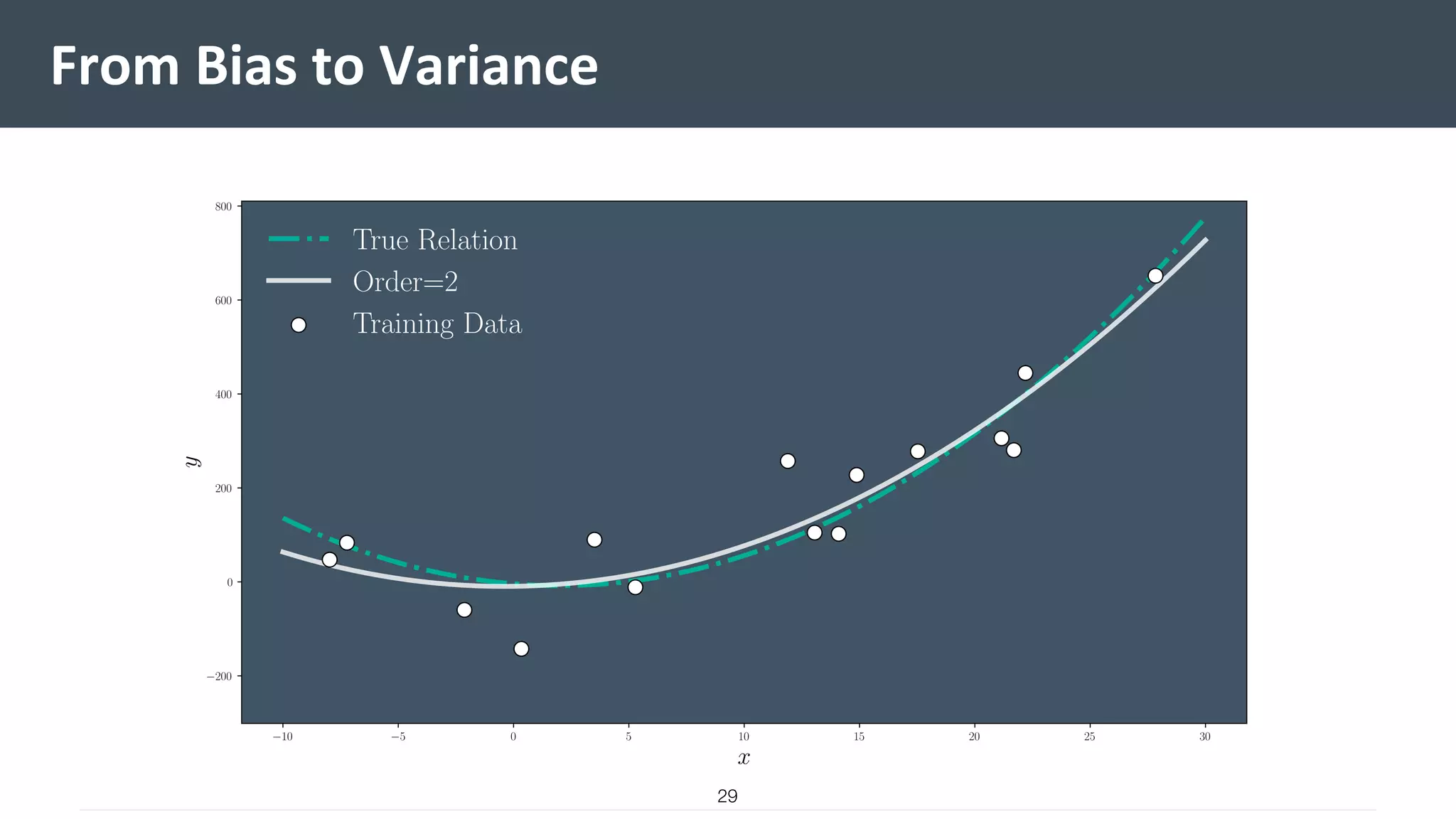

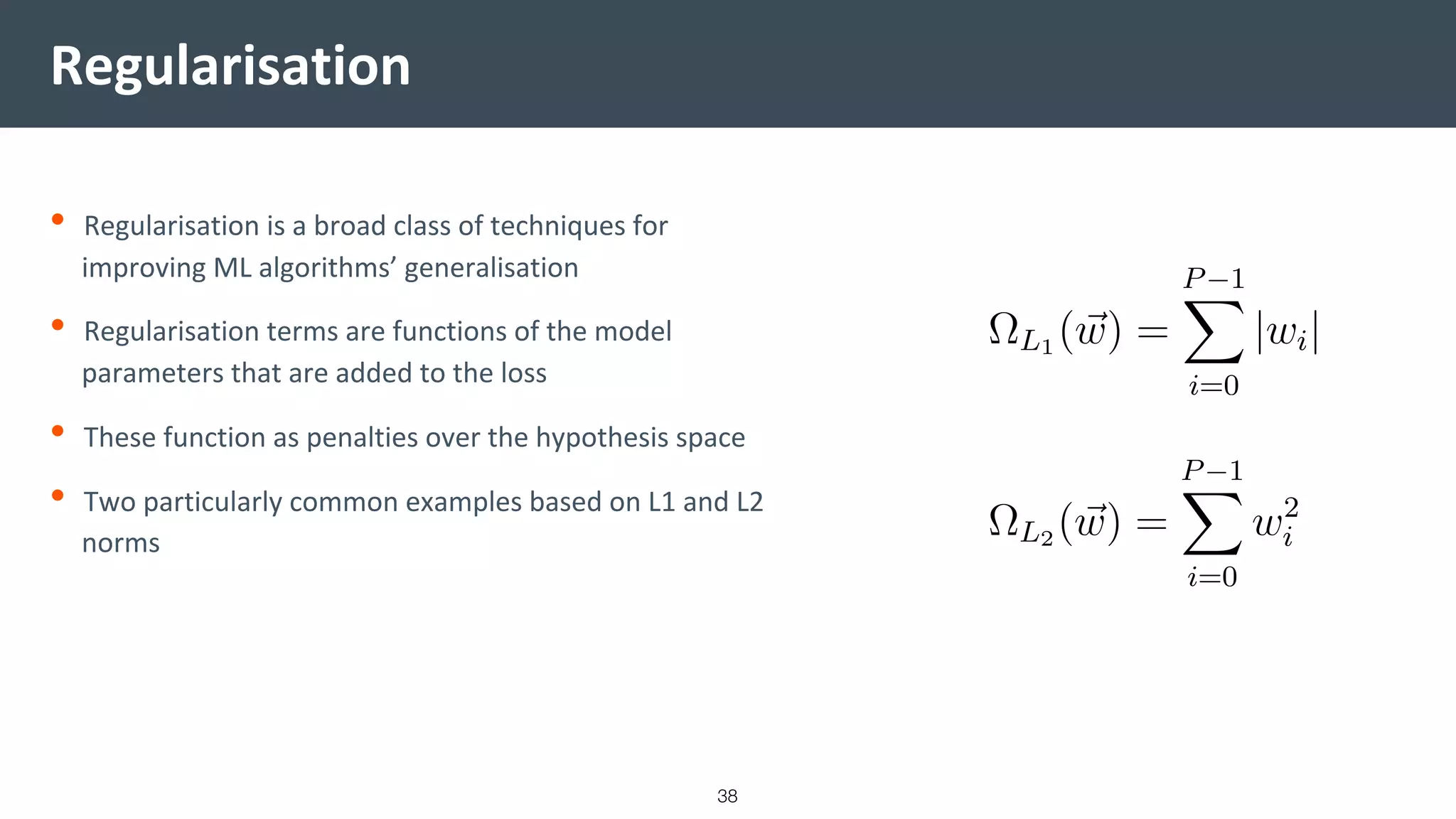

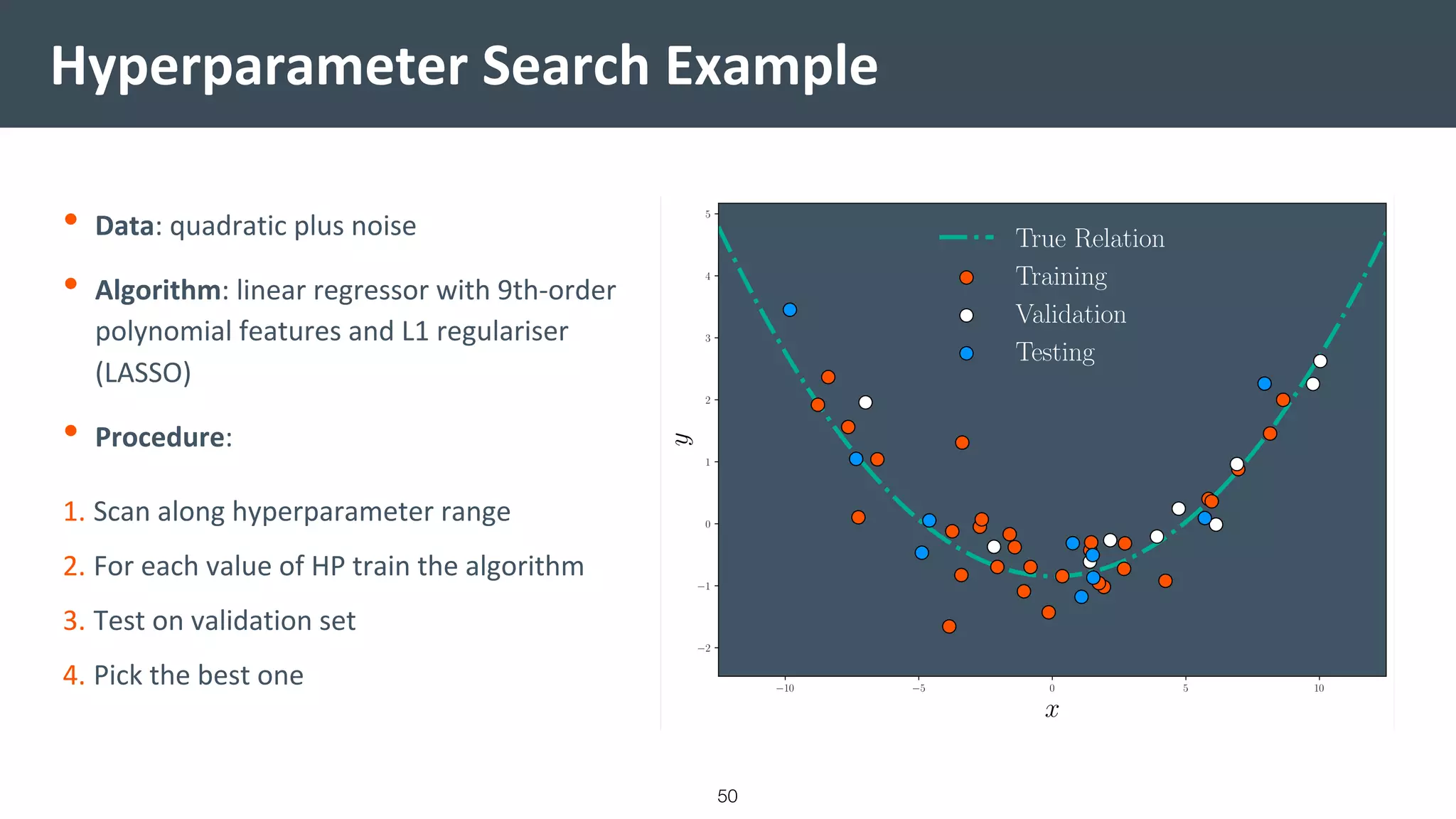

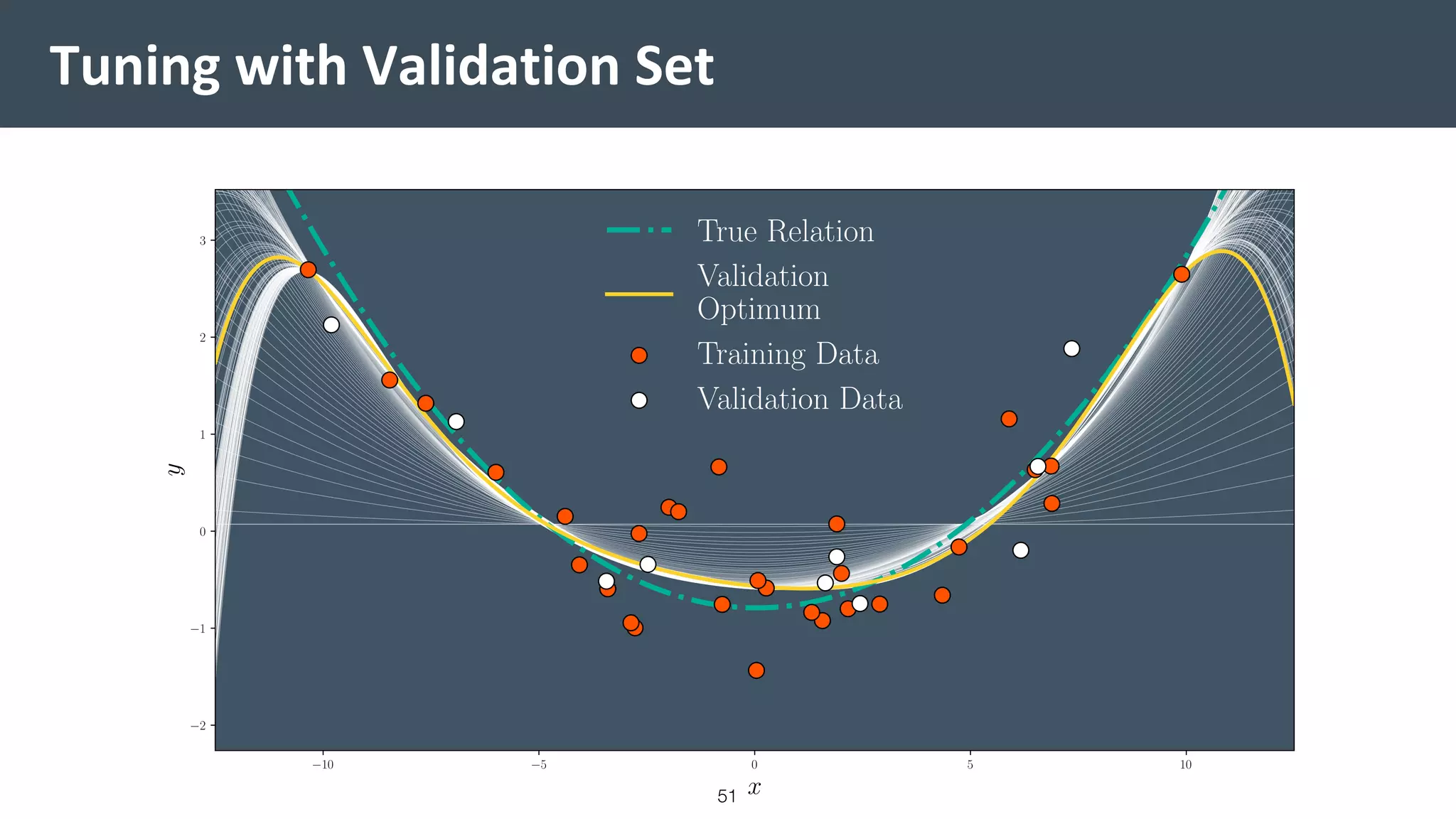

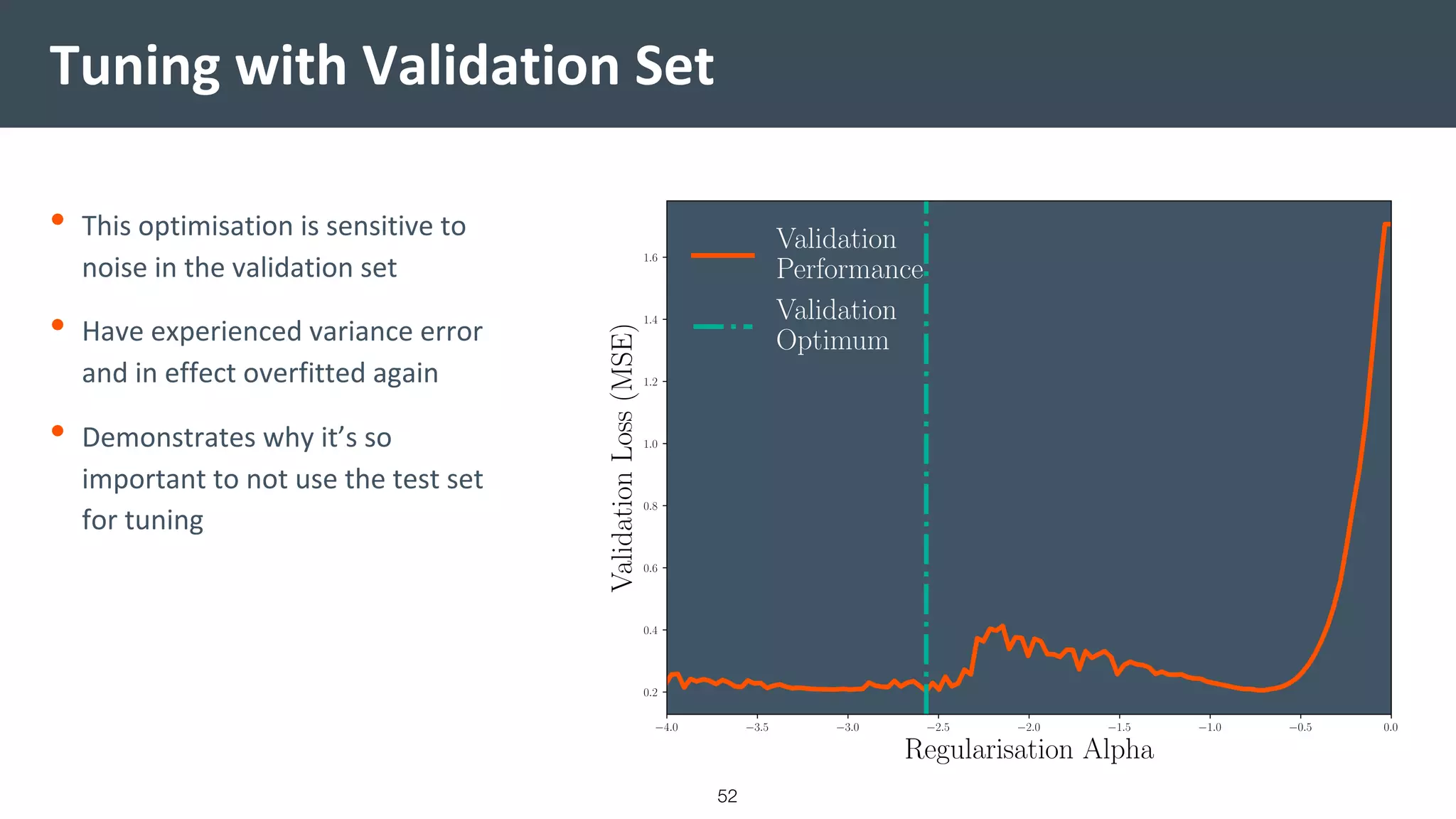

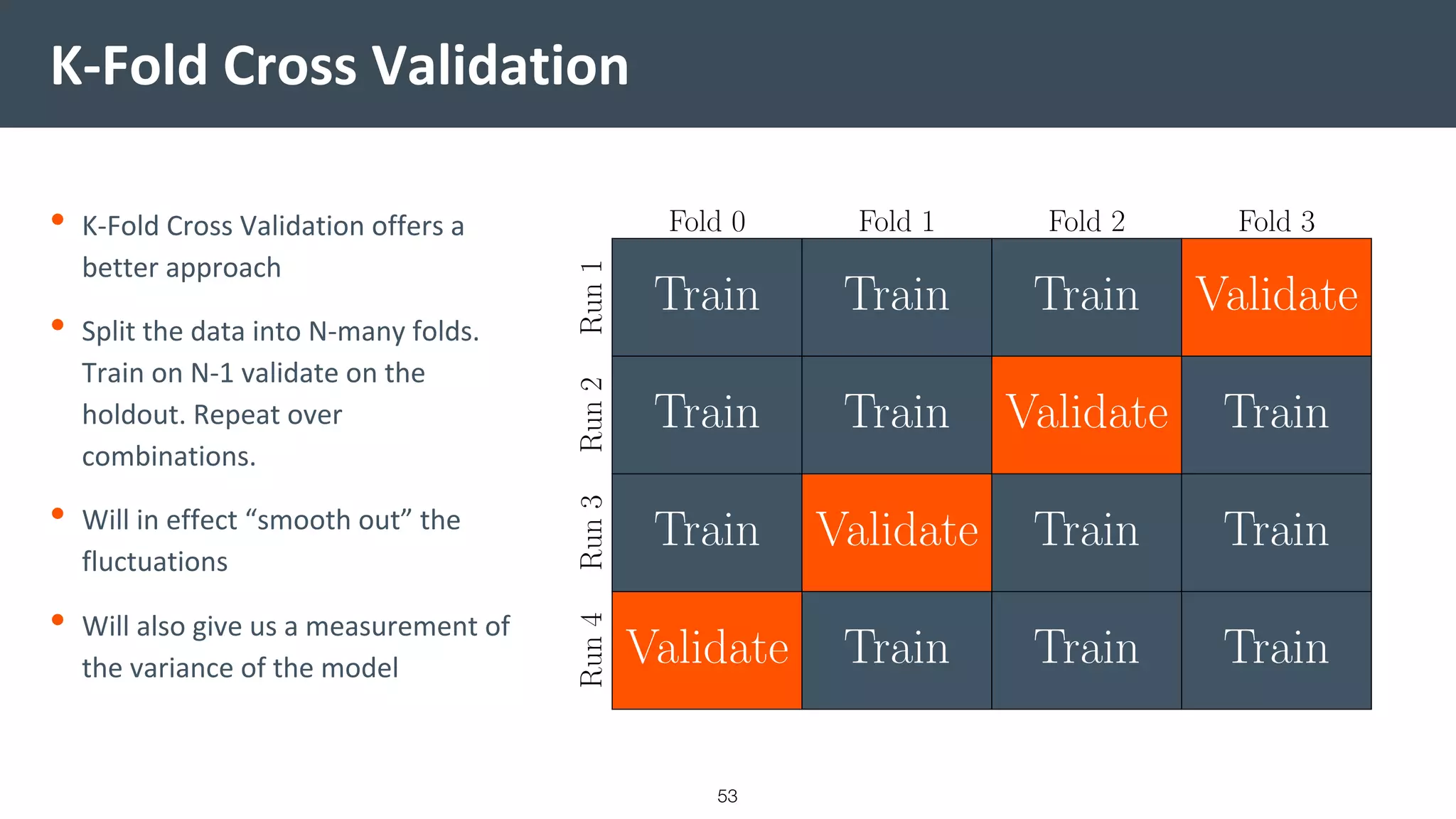

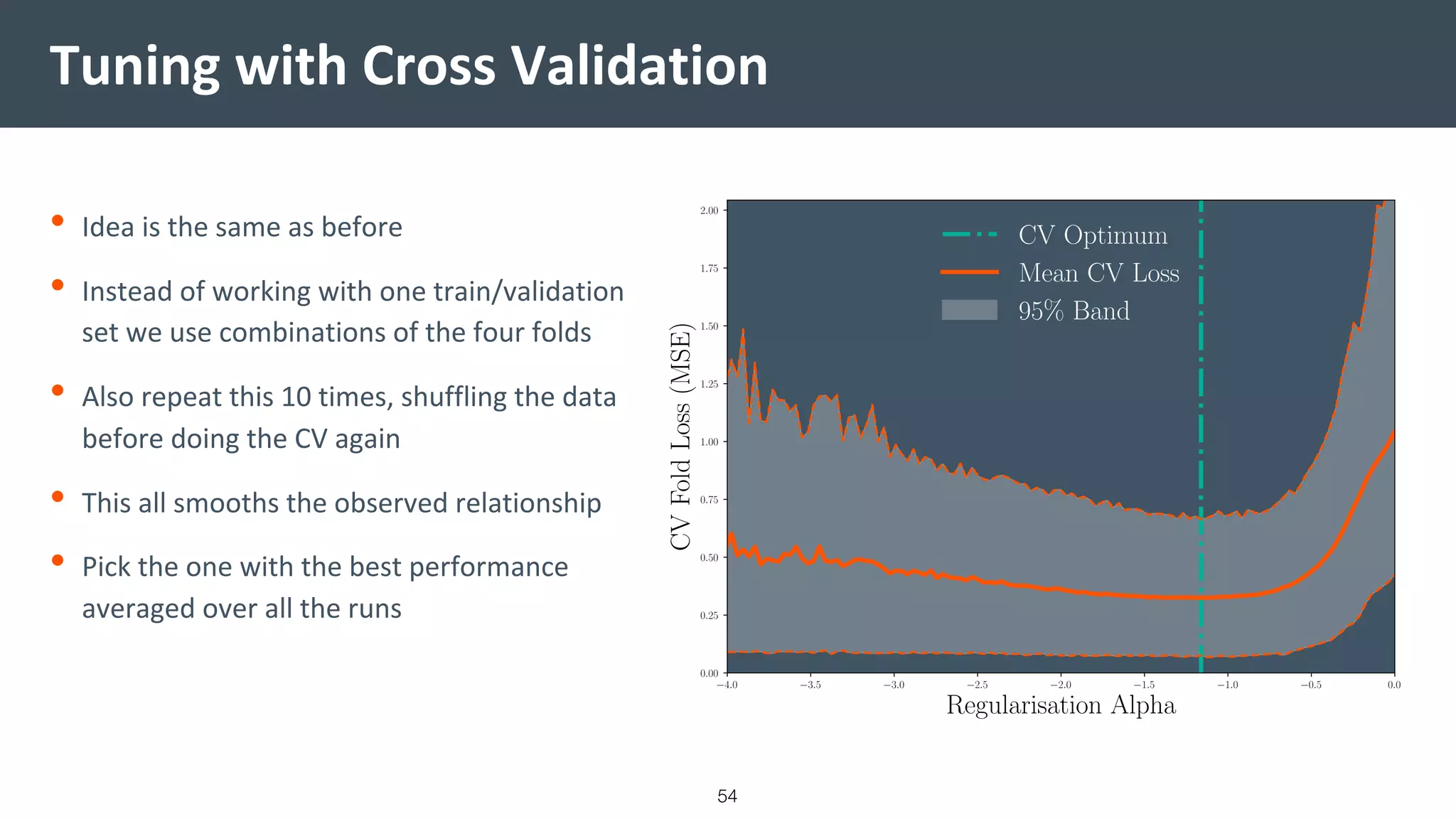

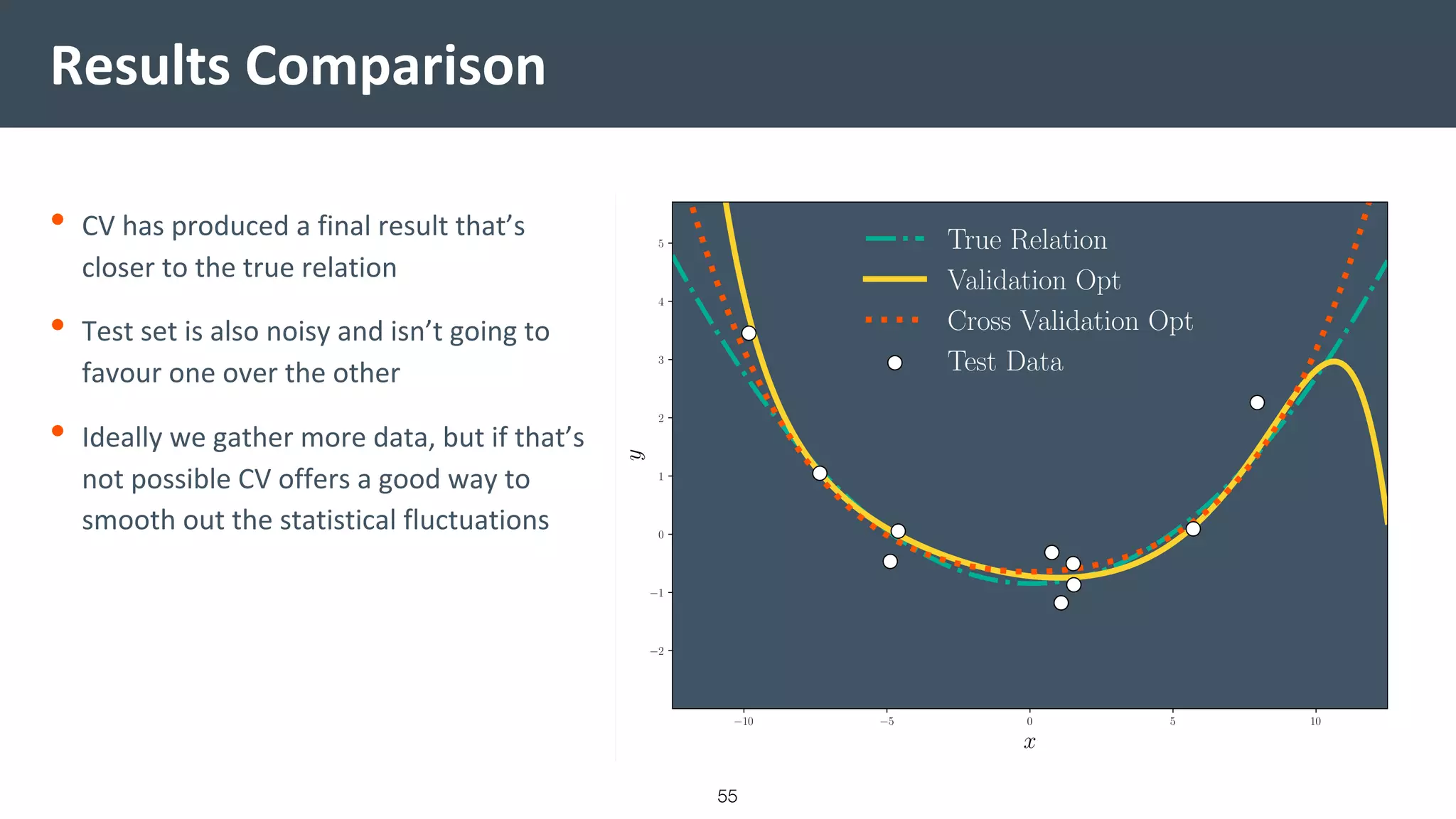

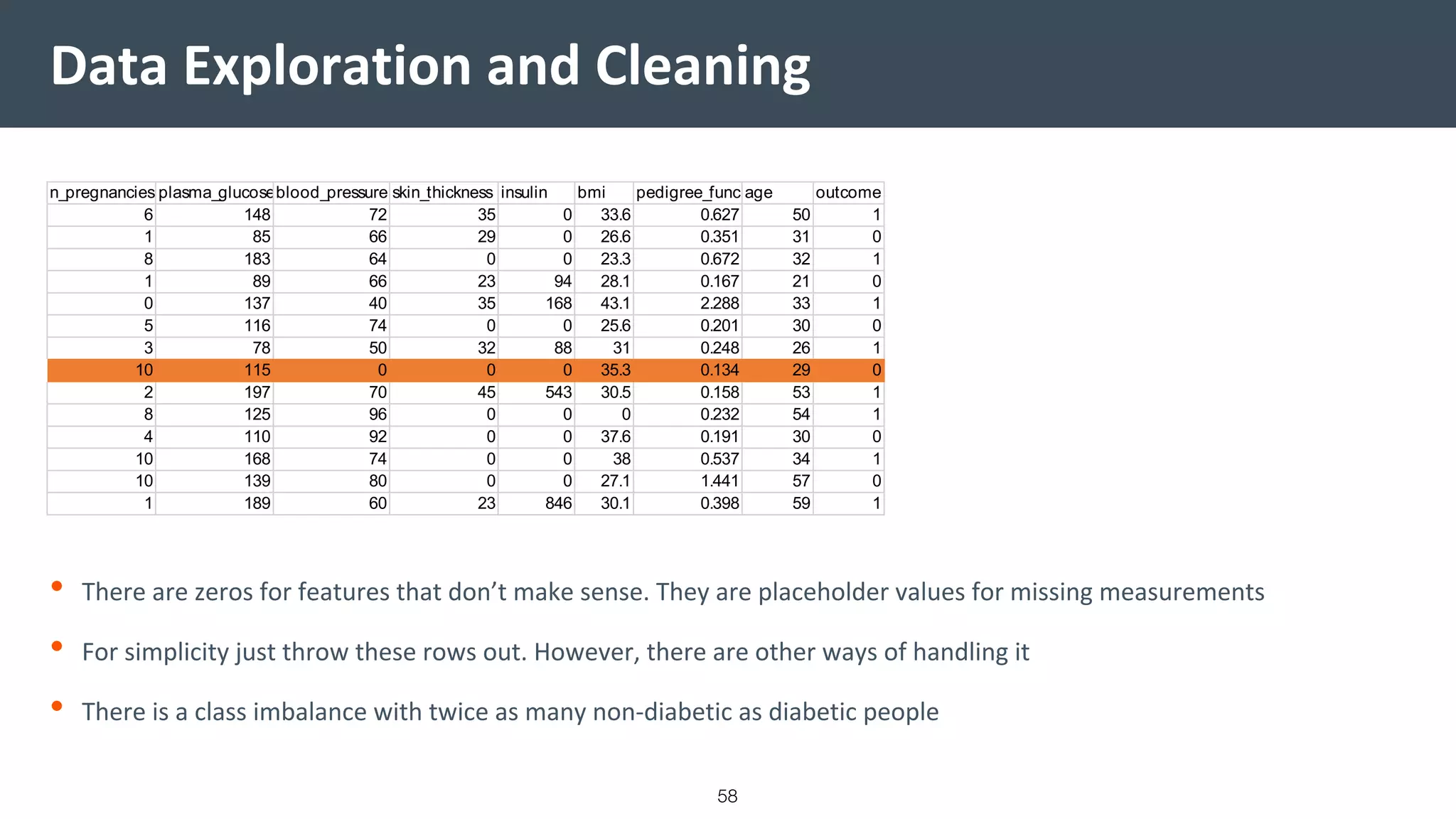

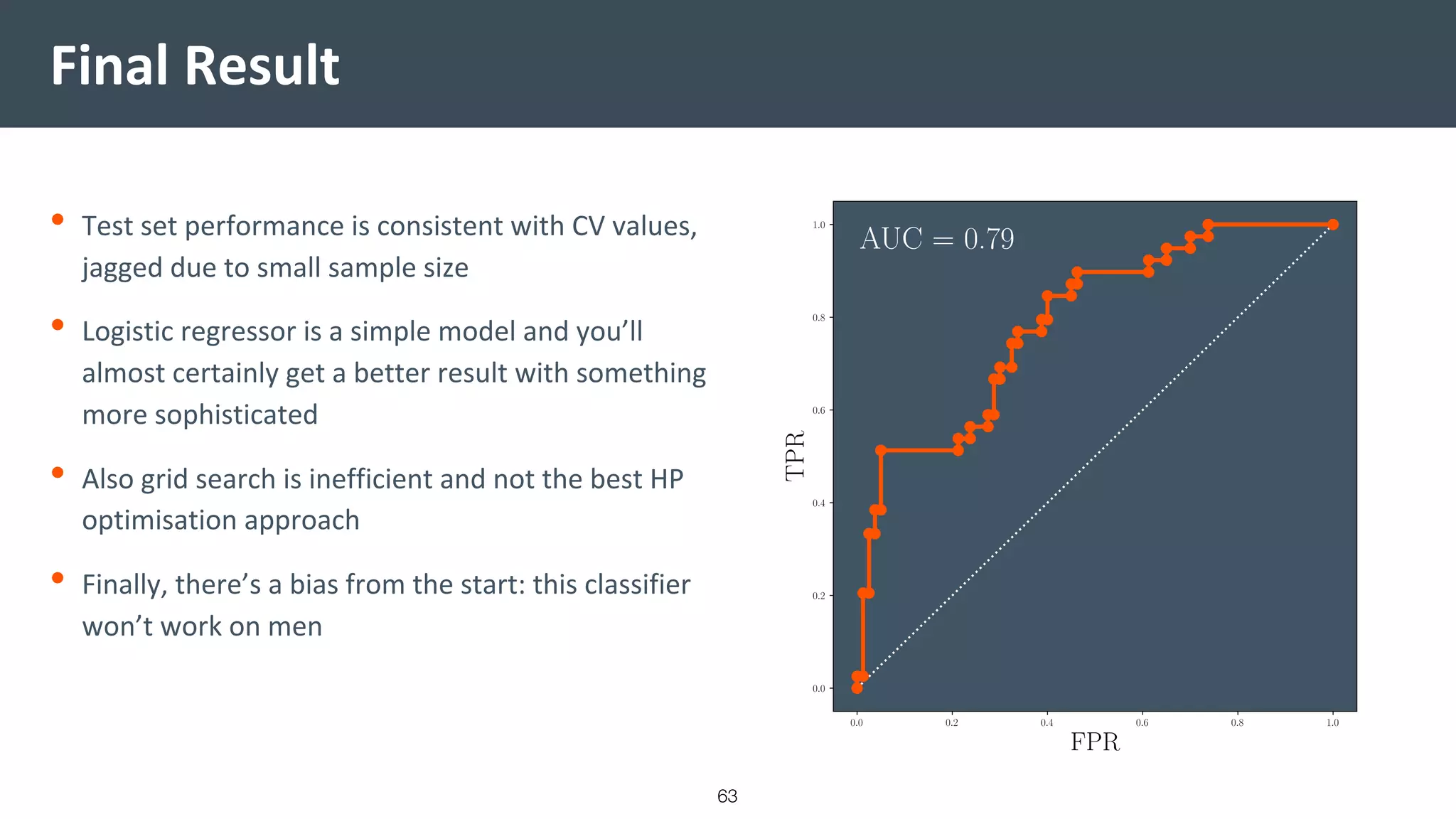

This document provides a comprehensive introduction to machine learning, covering key topics such as algorithm structures, model selection, and tuning techniques. It explains the importance of inductive bias, loss functions, and the empirical risk minimization process, illustrated with examples like linear regression and logistic regression. Additionally, it discusses practical aspects of machine learning, including data preparation, hyperparameter optimization, and the challenges of generalization in models.

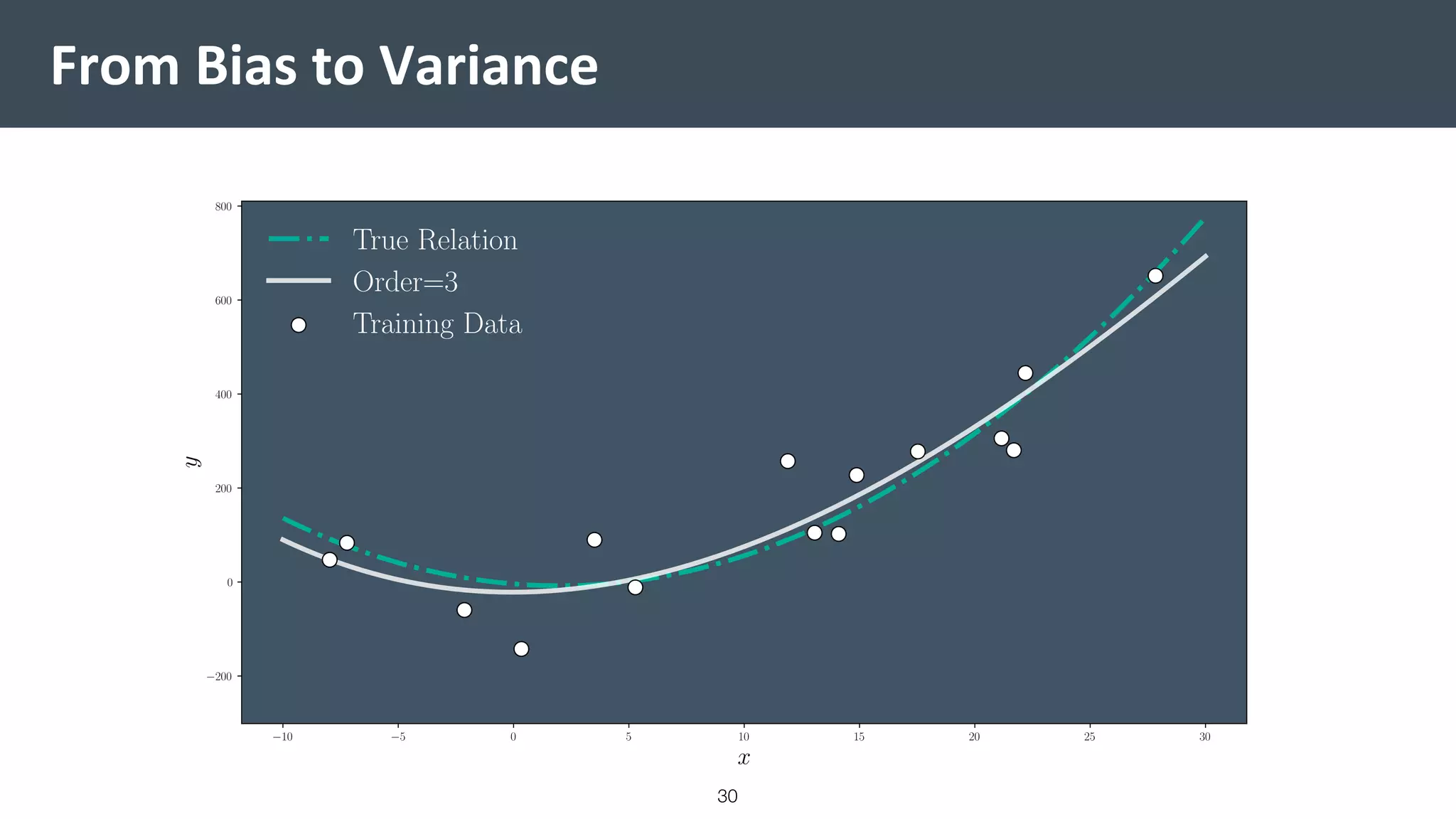

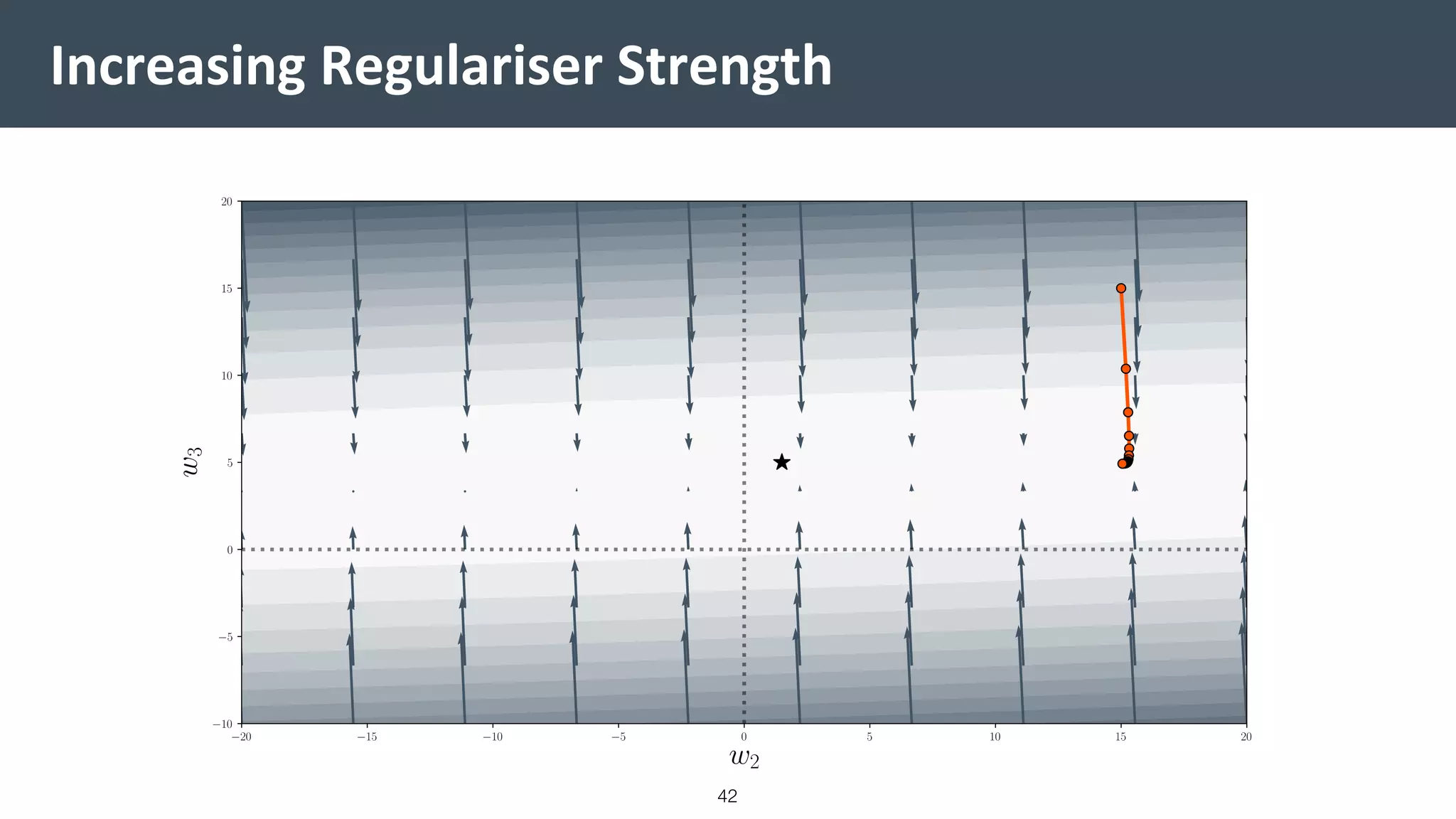

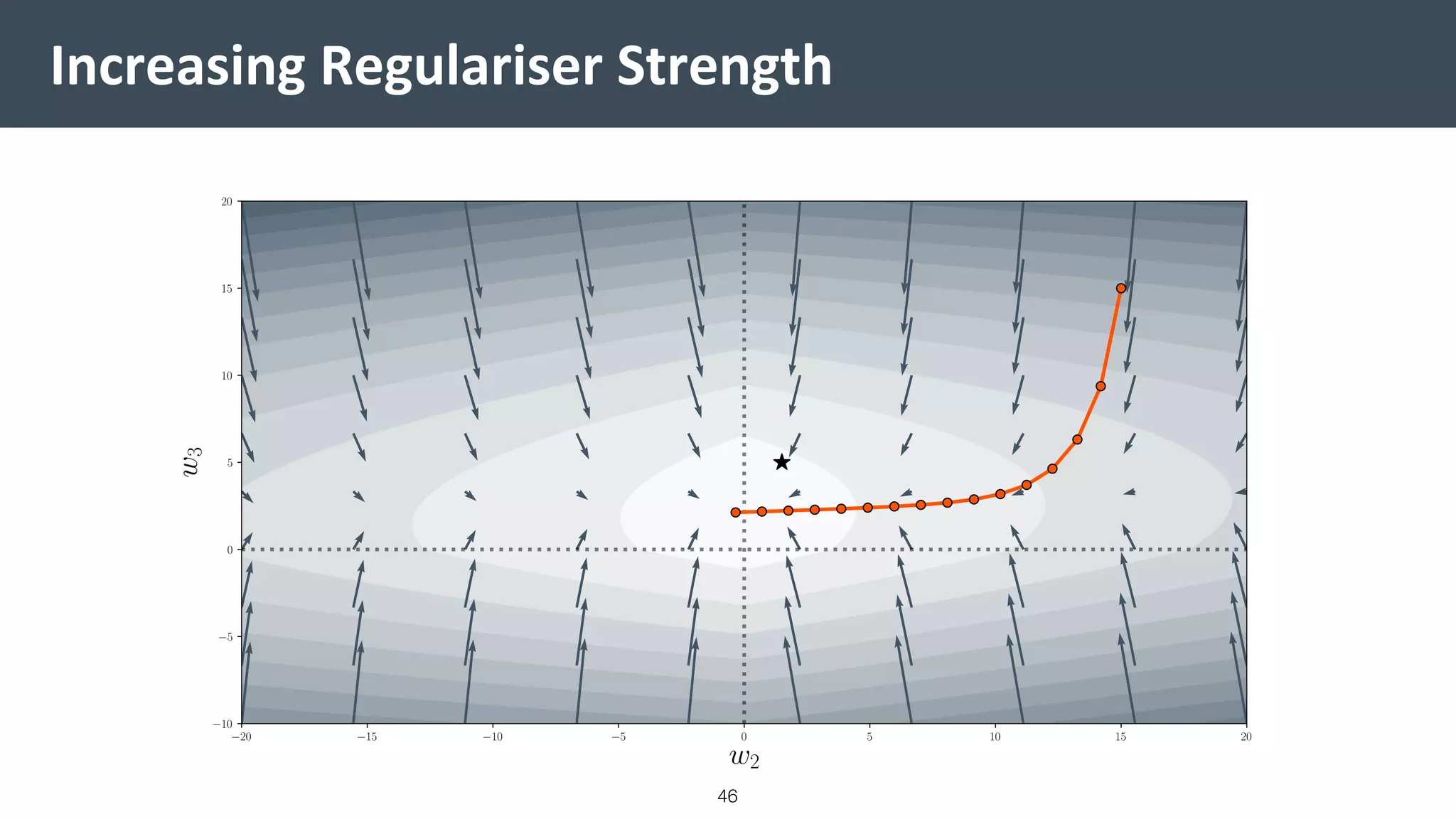

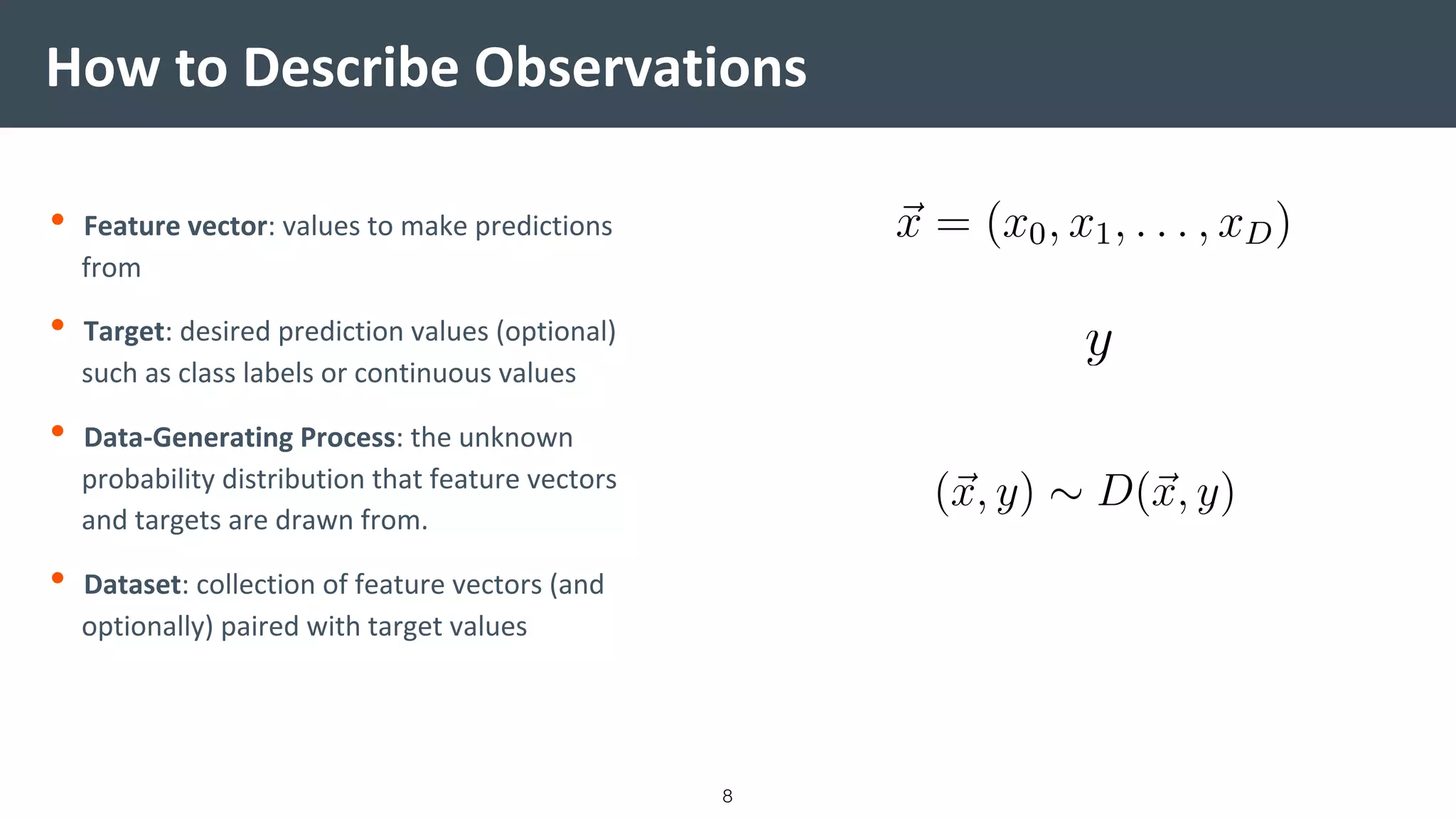

![Features and Data: Irises

9

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

petal length (cm)

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

petalwidth(cm)

Iris Features

Setosa

Versicolor

Virginica

[1.4 0.2][0]

[1.4 0.2][0]

[1.3 0.2][0]

[1.5 0.2][0]

[1.4 0.2][0]

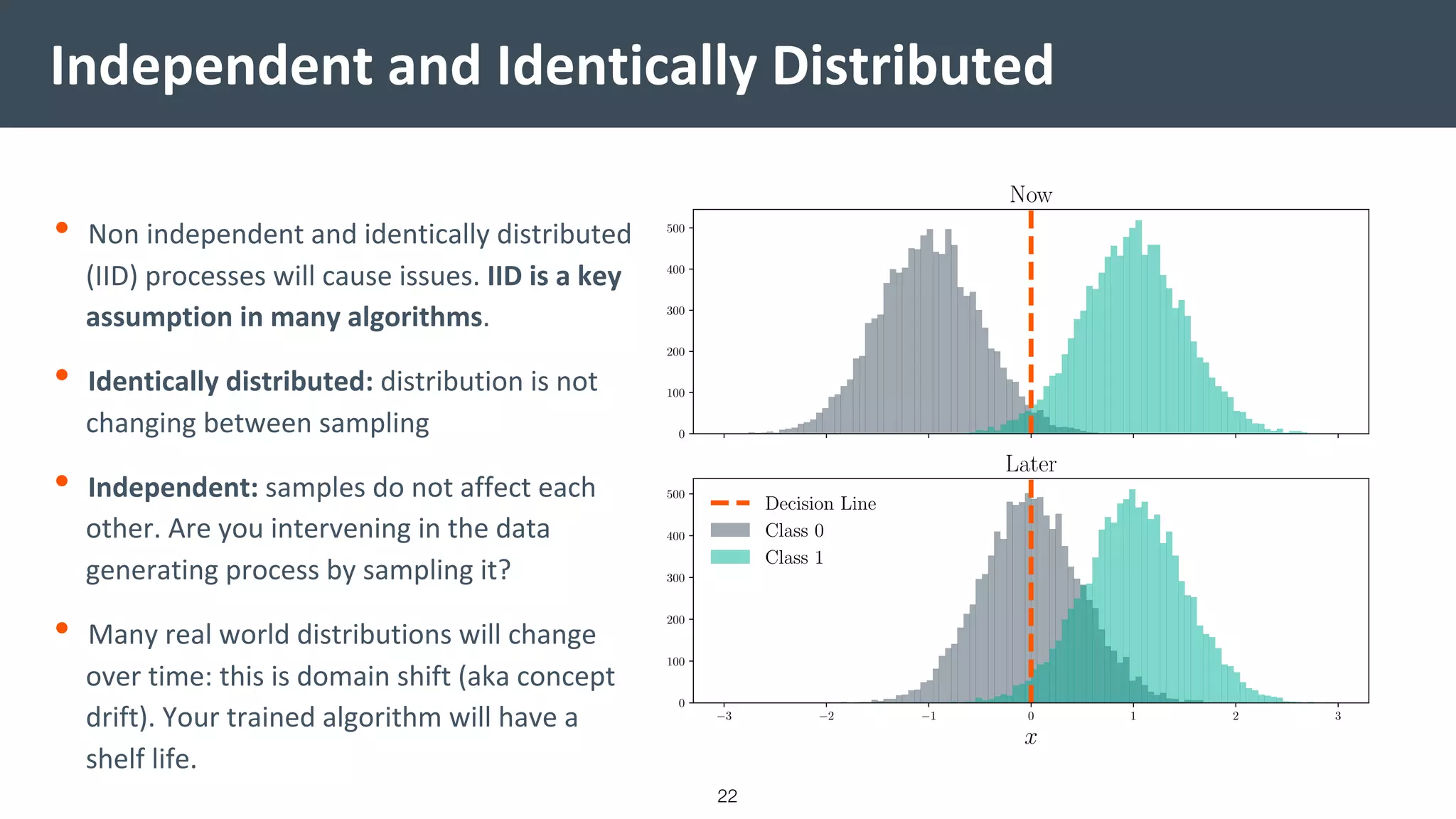

[6.0 2.5][2]

[5.1 1.9][2]

[5.9 2.1][2]

[5.6 1.8][2]

[5.8 2.2][2]

[4.7 1.4][1]

[4.5 1.5][1]

[4.9 1.5][1]

[4.0 1.3][1]

[4.6 1.5][1]

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

petal length (cm)

Iris Features

Setosa

Versicolor

Virginica](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ml-talk-1b-200409112817/75/Introduction-to-Machine-Learning-9-2048.jpg)