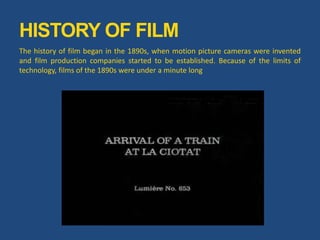

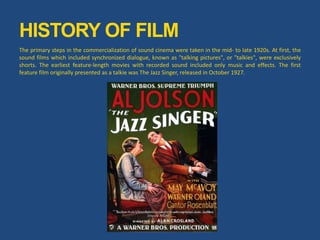

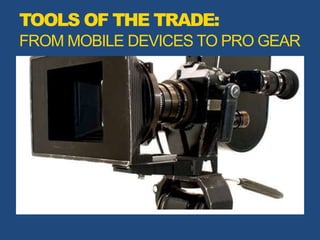

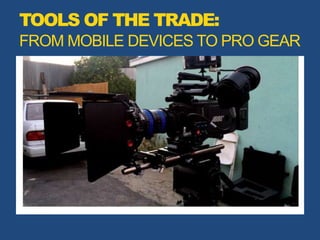

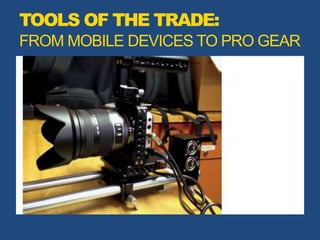

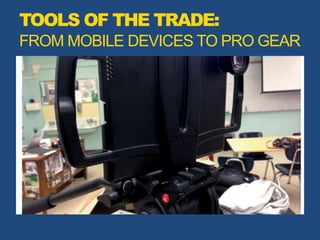

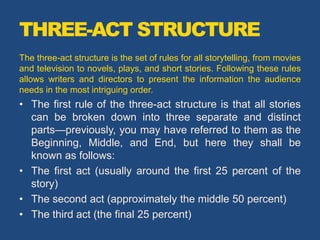

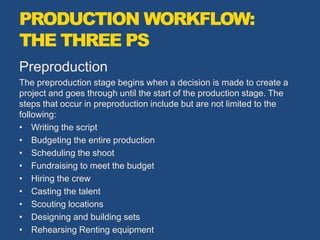

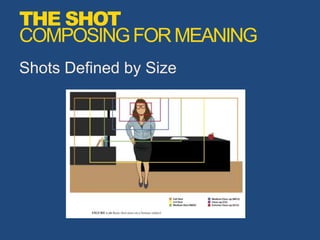

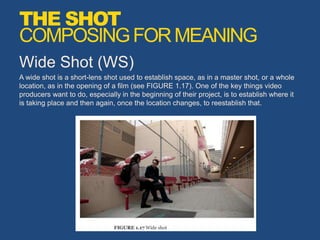

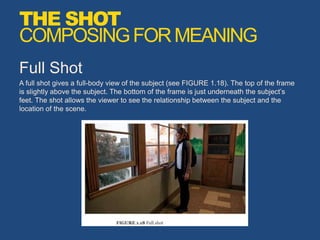

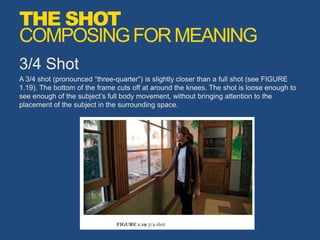

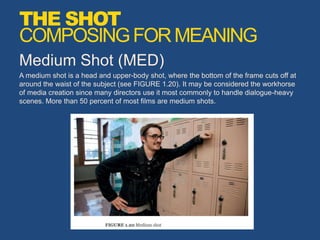

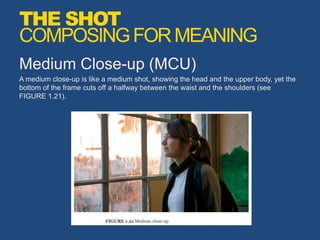

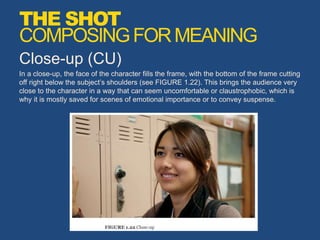

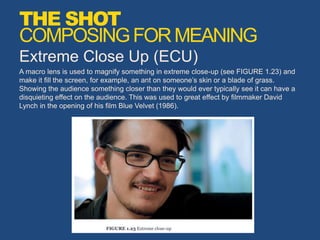

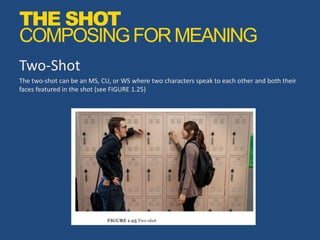

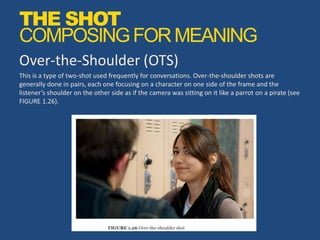

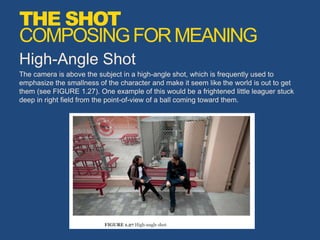

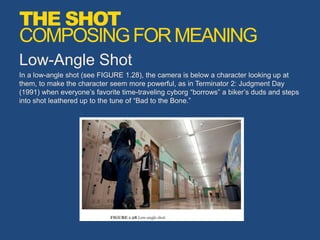

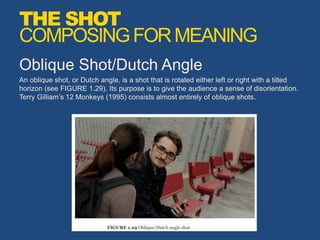

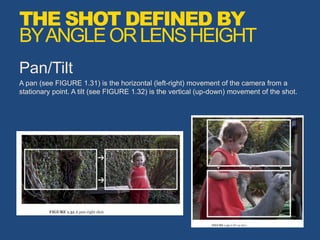

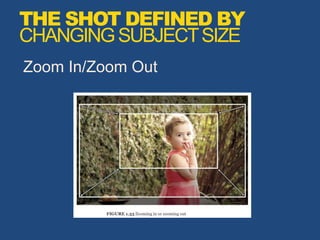

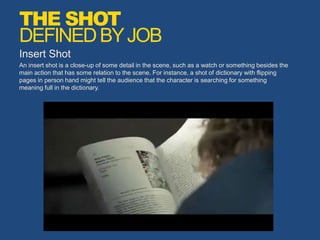

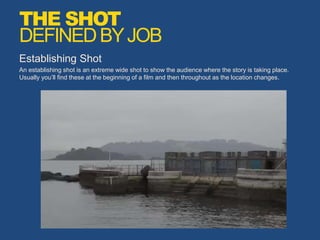

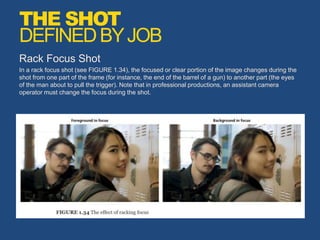

The document outlines the history and elements of filmmaking, starting from the invention of motion picture cameras in the 1890s to the introduction of sound in films in the late 1920s. It discusses various filmmaking techniques, the roles of crew members like producers and directors, and the three phases of production: preproduction, production, and postproduction. Additionally, it describes different types of shots and their significance in storytelling, emphasizing the importance of narrative structure in video production.