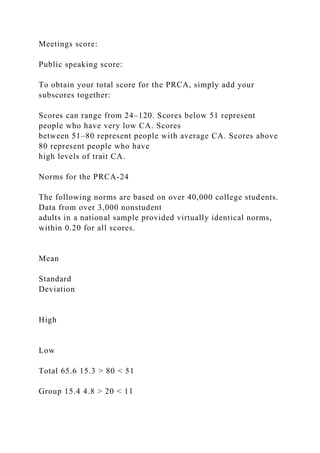

The document focuses on the importance of interpersonal communication in business and professional settings, illustrating how effective communication can enhance workplace relationships and overall professional success. It discusses various communication behaviors, the influence of technology on workplace interactions, and the significance of addressing negative emotions while maintaining professional relationships. The chapter emphasizes that strong communication skills are sought after by employers and are essential for building social connections that can mitigate workplace stress and improve job satisfaction.