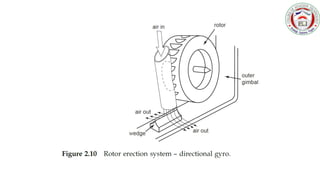

The document discusses the principles and components of gyroscopes, including their properties such as rigidity and precession, as well as the concepts of gyro drift (real and apparent) and transport wander. It details the mechanisms by which gyroscopic instruments like directional gyros and attitude indicators operate, including descriptions of pneumatic and electrical drive systems. Further, it outlines the processes for leveling and alignment of inertial navigation systems, addressing issues such as gimbal errors and drift calculations based on geographic latitude.