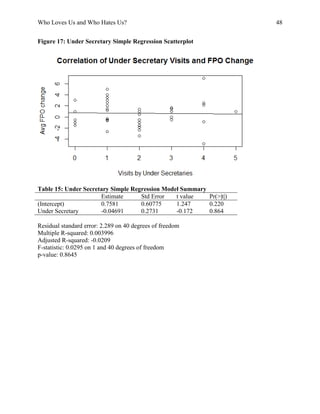

The document is an undergraduate thesis that explores the relationship between U.S. public diplomacy and foreign public opinion. It analyzes how various forms of U.S. public diplomacy, such as high-level visits, social media engagement, and press releases, have impacted changes in foreign public opinion from 2009 to 2016. Through regression analysis and analysis of variance, the thesis finds no statistically significant association between public diplomacy activities and changes in opinion. However, it reveals a slight trend where countries more inclined to view the U.S. favorably had greater increases in opinion, while less favorable countries had greater decreases.