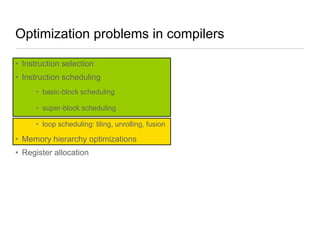

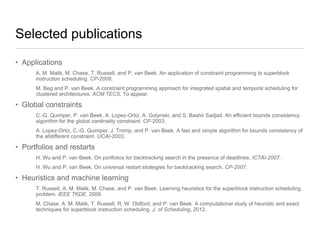

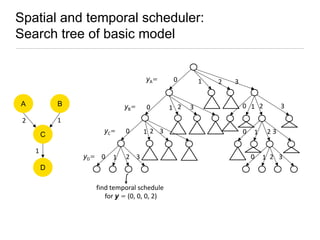

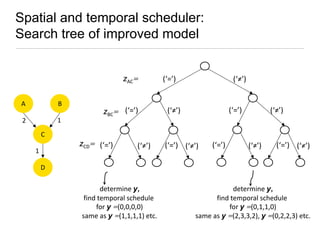

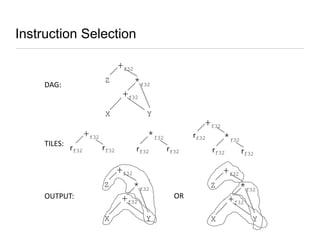

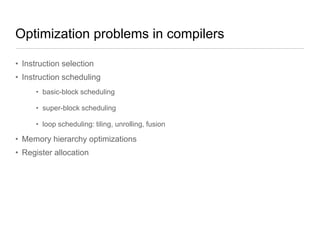

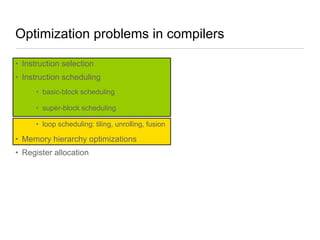

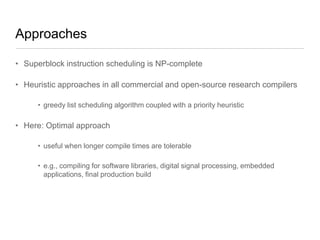

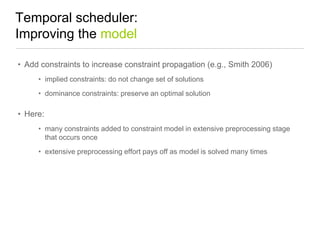

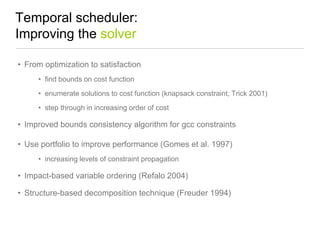

Constraint programming techniques were applied to compiler optimization problems like instruction selection, instruction scheduling, and register allocation. The techniques were able to find optimal solutions to some problems that were previously only solved heuristically. Constraint models were improved over time by adding implied constraints, dominance constraints, and preprocessing. Solvers were improved through techniques like restarts, portfolios, and machine learning of heuristics. The approach led to identifying and solving interesting subproblems with general applicability, like improved consistency algorithms for global constraints.

![Spatial and temporal scheduler:

Some related work

• Bottom Up Greedy (BUG) [Ellis. MIT Press „86]

• greedy heuristic algorithm

• localized clustering decisions

• Hierarchical Partitioning (RHOP) [Chu et al. PLDI „03]

• coarsening and refinement heuristic

• weights of nodes and edges updated as algorithm progresses](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ictai-2013-131125074429-phpapp01/85/Constraint-Programming-in-Compiler-Optimization-Lessons-Learned-31-320.jpg)