This document discusses effective academic writing, focusing on how to write proposals, theses, and publications using the IMRAD format. It emphasizes the importance of structuring the introduction, methods, results, and discussion sections to clearly convey research problems and findings. Additionally, it provides guidance on identifying research gaps, developing hypotheses, and ensuring that the writing is coherent and engaging.

![How your opening identify your power position

Visual and hearing impairments are associated

with cognitive decline in older people (Maharani

et al., 2018 – Age and Ageing)

Maintaining cognitive function in later life has become a public health

priority as the burden imposed by dementia in the ageing population has

increased more rapidly than that of most other diseases [1].

Trajectories of recall memory as predictive of

hearing impairment: A longitudinal cohort study

(Maharani et al., 2020 – PLOS One)

Hearing impairment has become a major concern for global health. The

2015 Global Burden of Disease estimates showed that hearing impairment

was the fourth leading cause of years lived with disability (YLDs) and those

YLDs increase from age 35 years to 64 years [1].

Healthcare system performance and

socioeconomic inequalities in hearing and visual

impairments in 17 European countries (Maharani

et al., 2020 – Eu J of Public Health)

As the world population ages, Europeans are among those enjoying the

longest life expectancies in the world: 75 years for men and 81 for women

[1].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/howtowriteagoodproposalmanuscriptanddisertation-240828212521-09d0c568/85/How-to-write-a-good-proposal_manuscript-and-disertation-pptx-11-320.jpg)

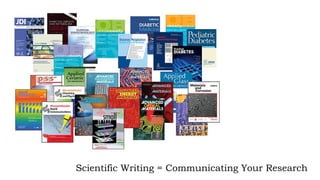

![Better: “Five out of seven recent studies (authors, dates) of the

relationship between race and birth weight in the United States found

that [pattern and example]. In contrast, Michaelson (date) found

[different pattern and example], while DiDonato (date) . . .”

Poor: “Smith and Jones (date) studied the relationship

between race and birth weight in the United States and found

[XYZ].”Michaelson (date) also studied the relationship between

race and birth weight and found [ABC]. [Separate descriptions

of results from five more studies on the topic.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/howtowriteagoodproposalmanuscriptanddisertation-240828212521-09d0c568/85/How-to-write-a-good-proposal_manuscript-and-disertation-pptx-17-320.jpg)

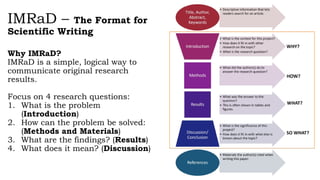

![Better: “Demographic characteristics and attitudinal factors (table A)

were drawn from the questionnaire and most health indicators from

the medical records (table B). An exception was asthma, for which

information was available from both sources.”

This description coordinates with tables (not shown) that organize

variables by data source and major conceptual groupings, eliminating

the need to specify the source for every variable individually.

Poor: “Age, sex, race, marital status, number of children, income, and

educational attainment were taken from the demographic section of the

questionnaire. Attitudes about [long list] were taken from the attitudinal

section of the questionnaire. Medical records provided information about

[long list of health items]. Asthma was also asked about on the

questionnaire.”

This description is unnecessarily long, repeating information that is far

more easily organized in a table.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/howtowriteagoodproposalmanuscriptanddisertation-240828212521-09d0c568/85/How-to-write-a-good-proposal_manuscript-and-disertation-pptx-20-320.jpg)