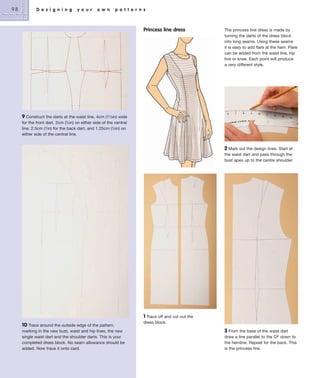

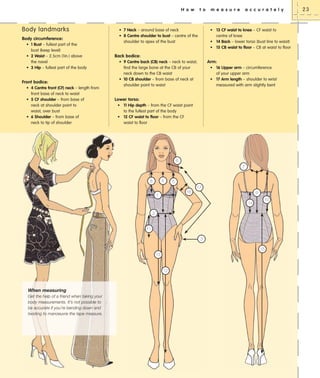

The document provides guidance on measuring the body accurately for sewing patterns. It includes a body measurement chart with explanations of key body landmarks to measure, such as bust, waist, hip, shoulders, arms, and torso. Readers are advised to remove outer clothing and have a friend help take accurate measurements. The correct techniques for using a measuring tape are explained. Sample measurements for a UK size 12/US size 8 are provided for comparison. Measuring accurately is important for obtaining a well-fitted garment.

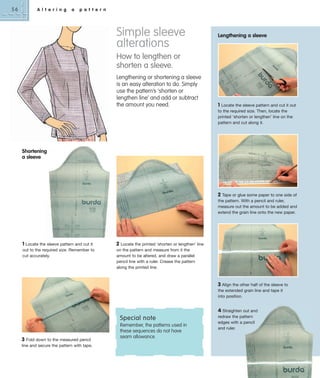

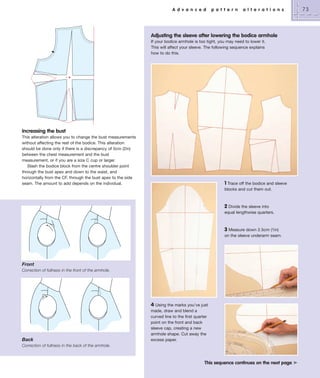

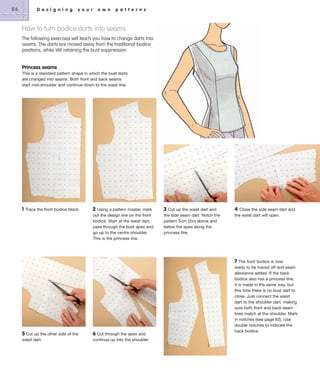

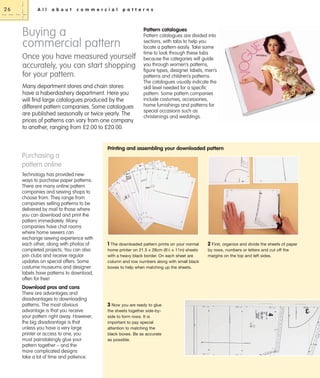

![S i m p l e

b o d i c e

a l t e r a t i o n s

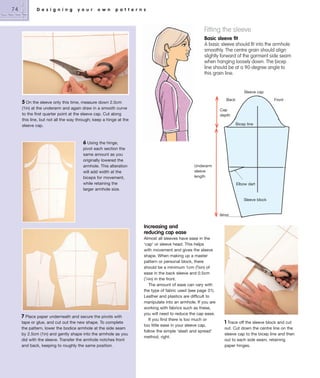

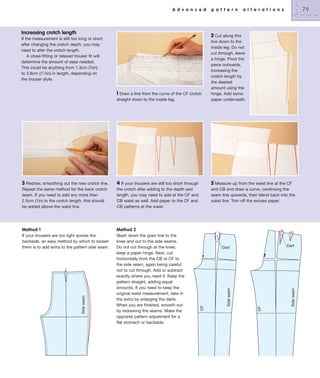

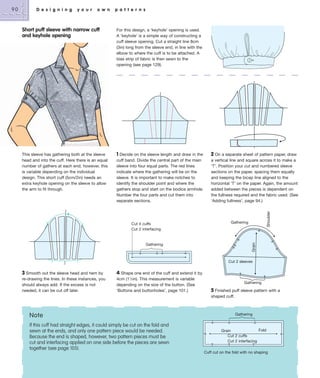

Method 3: increasing the bust by

small amounts, 2cm (3⁄4in) or less

4 Fold out the dart and check for

steps and gaps in the new side

seam. It is important to check what

implications your alterations may

have for the rest of the pattern

before cutting it out.

5 With the dart still folded, redraw the

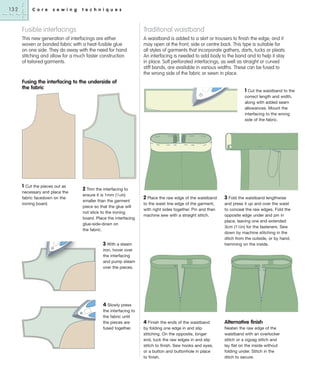

When a small amount extra is needed to

increase the bust, the seam allowance can be

used. Taking too much fabric from the seam

allowance will weaken your garment, so small

amounts only are possible, for example, 2cm

(3⁄4in) in total. Adding to the bust through the

side seams will also add to the armhole

circumference. To ensure the sleeve will fit

correctly, you will need to add the same

amount to the sleeve pattern and to the back.

2 Fold out the bust dart.

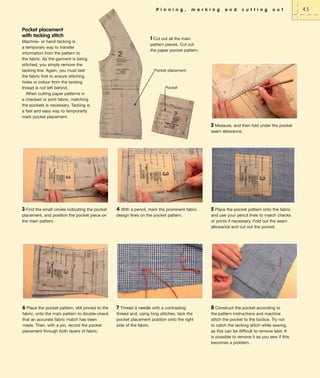

1 Cut out your pattern pieces in the correct

size and add extra paper to the side seams

of the bodice and sleeve (if there is no seam

allowance included on the pattern).

3 Measure out from the side seam the

amount to be added (up to 5mm [3⁄16in]).

side seam, smoothing out any steps

and gaps using a ruler.

6 The finished pattern.

4 With a pattern master, blend the added

measurement into the side seam while

the dart is folded closed.

6

Adding to the bust

circumference also

increases the armhole.

Add the same amount to

the sleeve bicep width.

5 Keeping the dart folded closed, cut

along the new side seam line.

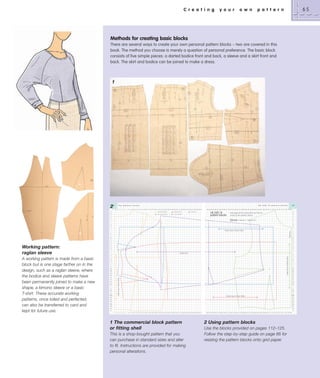

55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/howtouseadaptanddesignsewingpatterns-140126122350-phpapp01/85/How-to-use-adapt-and-design-sewing-patterns-56-320.jpg)