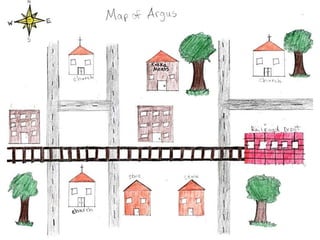

Dr. Laurence Musgrove's document discusses the concept of 'handmade thinking,' emphasizing the importance of drawing in enhancing reading engagement and comprehension. By utilizing innovative visual formats and guided practice, students can improve problem-solving and critical thinking skills through artistic expression. The document outlines a structured approach for implementing these strategies in the classroom, including collaborative sharing and evaluation of handmade responses.