This document provides an overview of logical approaches to analyzing the security of distributed systems. It discusses cryptographic protocols, web services, and modeling tools. The document is divided into three sections. The first section describes cryptographic protocols and web services. The second section discusses tools for modeling these systems using first-order logic. The third section presents symbolic models for cryptographic protocols and a proposed model for analyzing web services security.

![10 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

have been performed, the logical consequence problem is decidable. This re-

sult is based on a refinement of resolution based on an ordering in which every

atom without variables is greater than only a bounded number of other atoms.

This presentation is followed by its (unpublished) extension to well-founded

orderings I have obtained with Mounira Kourjieh when solving cryptographic

protocol analysis problems.

Modelling. Now that the reader is equipped with a “survival toolkit” in first-

order logic I present the formal models on which the analysis is performed.

Chapter 6 includes an article written in collaboration with M. Rusinowitch on

the compilation of standard cryptographic protocol specifications into active

frames. These are a simplified formal model of protocol participants in which

only the global effects, not the individual operations, of the participant are taken

into account. Also in this chapter I introduce symbolic derivations in which all

operations must be atomic. In contrast with active frames, which have an in-

tuitive semantics, and with process calculi, that rely on standard programming

constructions, symbolic derivations are designed to ease the reasoning on pro-

tocol participants and on the intruder, at the cost of a difficulty to relate this

model of computation to standard constructions.

In contrast with cryptographic protocols in which entities usually terminate

their participation to the protocol after a few execution steps, Web Services

may exhibit a rich behavior. Trust negotiation in particular usually ends once a

fixpoint is reached. Thus in order to take into account the access control part of

the Web Service specifications we need to consider a framework in which loops

are allowed. In collaboration with Philippe Balbiani and Marwa ElHouri I have

proposed one such framework in [21, 22], from which Chapter 7 is extracted.

Results obtained. The last part of this document presents the decidability

or combination results I have obtained since I obtained my Ph.D. In a first

chapter I present a synthesis of several results obtained around the decidability

of the insecurity problem of cryptographic protocols when only a finite number of

message exchanges by honest agents are allowed. Instead of focusing on each of

the settings considered, I have tried to how these different results are connected

one with another. In doing so I have assumed that the reader is already familiar

with the proofs and techniques employed in the articles [61, 67, 62].

Then in Chapter 9 I present the results obtained while I was invited in the

Cassis project at INRIA Nancy Grand Est. I have worked there in collaboration

with M. Rusinowitch, M. Turuani, and with two Ph.D. students, Mohammed

Anis Mekki and Tigran Avanesov. We have worked on the application of the

techniques developped primarily for cryptographic protocol analysis to solve ba-

sic orchestration problems, which are both special reachability problems. With

M.A. Mekki the study was focused on building a complete tool that takes in its

input a description of the available services in an Alice&Bob-like notation and

a description of the goal of the orchestration, and produces a deployment-ready

validated orchestrator service. At the time of writing, that service is deployed](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-10-320.jpg)

![1.3. DOCUMENT OUTLINE 11

as a tomcat servlet, but all the cryptography is implemented within the body

of the SOAP messages. With T. Avanesov we have considered a multi-intruder

extension of the standard cryptographic protocol analysis setting. When per-

forming security analysis, this setting permits us to model situations in which

several intruders are willing to collaborate one with another, but cannot com-

municate directly, and thus have to pass the information they want to exchange

through honest agents. When composing Web Services, we look at a distributed

orchestration problem: several partners are willing to collaborate, but they do

not wish to share all the information they have. The problem then is to decide

whether the participants’ security policies are flexible enough to allow them

to collectively implement the goal service. Generally speaking, this problem

is strictly more difficult than standard orchestration (or cryptographic protocol

analysis) given that in addition to a decision procedure for the case of Dolev-Yao

like message manipulations, we have obtained an undecidability result when the

equational theory that defines the operations is subterm and convergent.

Finally in Chapter 10 I present some work on the equivalence of symbolic

derivations. The problem is to determine whether an intruder can observe dif-

ferences in the execution of two different protocols. A preliminary result ob-

tained in collaboration with M. Rusinowitch was published in [75]. In that

paper we have provided a more succinct proof of the decidability of this prob-

lem for subterm convergent equational theories, a result originally obtained by

M. Baudet [27]. In this chapter I present a criterion that actually permits one

to reduce this equivalence problem to the reachability analysis performed when

considered the usual trace properties. I believe that the reduction can easily be

implemented in reachability analysis tools such as CL-AtSe or OFMC, and thus

may be of practical interest.

Epilogue. This document ends with a last chapter on the future research di-

rections stemming from the results obtained so far. A one-sentence summary

would be more of the same, but differently. While I plan to continue the work

around reachability analysis problems, I also plan to explore further the side-

ways, namely:

• to work on the potential applications to safety analysis;

• to explore further the relation between reachability analysis and first-order

automated reasoning techniques;

• to obtain a comprehensive framework for service composition that also

takes into account trust negotiation, and as a consequence to relate more

formally the models for protocols and Web Services presented in this doc-

ument;

• to extend the modularity results obtained to address the modular verifi-

cation of aspect-based programs.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-11-320.jpg)

![16 CHAPTER 2. CRYPTOGRAPHIC PROTOCOLS

The most common types are:

Secret key cryptosystems: this type of cryptography has been the only type

of cryptography until the 1970s. It relies on a secret piece of information,

called a secret key, known only within a small group. Every member of

this group can both cipher and decipher messages with the key, while

agents outside of it can neither cipher nor decipher the encoded message.

Instances of secret key cryptosystems are the Enigma [214], DES [165],

3DES [169], and the current AES [170]. Given a message M , and a secret

key sk(k) we denote:

encs (M, sk(k)):the encryption of M with the key sk(k)

decs (M, sk(k)):the decryption of M with the key sk(k)

Public key cryptosystems: the first (tentative) publication [158] on public

key cryptography was met with skepticism, as in the words of a reviewer:

“Experience shows that it is extremely dangerous to transmit key

information in the clear.” 1

The first accepted paper on the topic was the presentation by Diffie and

Hellman [104] of a clever usage of exponentiation in modular arithmetic.

The result of their analysis was the possibility to compute a couple of

keys (pk(k), sk(k)) such that the messages encrypted with the key pk(k)

can be decrypted only with the key sk(k), and such that sk(k) cannot

feasibly be computed from pk(k). Thus the key pk(k) can be published

as a phone number would be, and any participant can send information

only to the agent knowing the key sk(k), given that only that agent can

decrypt, i.e. understand. Examples of public-key cryptosystems include

RSA [186, 31, 179, 180], ElGamal [116]. Given a message M , a public key

pk(k) and a secret key sk(k) we denote:

encp (M, pk(k)) the encryption of M with the key pk(k)

decp (M, sk(k)) the decryption of M with the key sk(k)

Signature cryptosystems: the asymmetry of public key cryptosystems can

also be employed to authenticate the creator of a message. The sender

signs the message he wants to send with a secret key sk(k). Anybody

knowing the public key pk(k) can then verify that the signature was com-

posed with the key sk(k), and thus originates from the possessor of that

key. Given a message M , a public key pk(k) and a secret key sk(k) we

denote:

sign(M, sk(k)) the signature of M with the key sk(k)

verif (M , M, pk(k)) the check that M is the signature of M with

the inverse of the key pk(k)

1 http://www.merkle.com/1974/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-16-320.jpg)

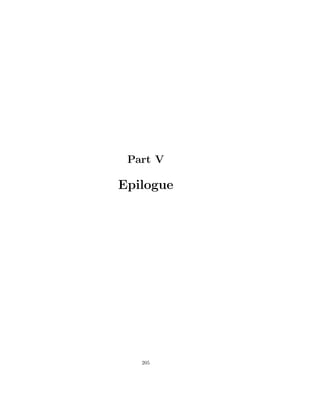

![2.1. CRYPTOGRAPHIC PROTOCOLS 17

Other functions are employed to construct messages such as the concatena-

tion M1 , M2 of two messages. We also consider the modeling of mathematics

functions such that the bitwise exclusive-or or the modular exponentiation, and

will add the corresponding symbols as necessary.

2.1.2 RFCs

Cryptographic protocols are published and endorsed by various governmental

or private organizations. These organizations can be formed to support one spe-

cific (set of) protocols, such as the “Liberty Alliance”, or have a more general

interest in one domain, such as the “Oasis Open consortium” or the “World

Wide Web Consortium”, for respectively the transmission and representation

of information in the XML format or the Web. The Internet Engineering Task

Force (IETF) is particularly important as an organization focusing on the basic

protocols employed in the computer-to-computer communications, and on the

interoperability of their implementations. Transport Layer Security [102, 103]

(TLS) is specified by a Request for Comments (RFC) document, as are some

protocol proposals in early stages, such as RFC 2945 that describes the SRP

Authentication and Key Exchange System. In the latter case implementation

issues are not discussed, but the principle of the protocol is presented. Often

such documents contain a finite state automaton describing the different states

in which a program implementing the protocol can be as well as the possible

actions in each state, and/or the intended sequence of messages between par-

ticipants in the protocol, as in Figure 2.1.

Client Host

U =<username> →

← s =<salt from passwd file>

Upon identifying himself to the host, the client will receive the

salt stored on the host under his username.

a =random()

A = g a %N →

v =<stored password verifier>

b =random()

← B = (v + g b )%N

p =<raw password>

x = SHA(s|SHA(U |” : ”|p))

S = (B − g x )(a+u∗x) %N S = (A ∗ v u )b %N

K =SHA Interleave(S) K =SHA Interleave(S)

Figure 2.1: Annotated message sequence chart extracted from the RFC 2945

(SRP Authentication and Key Exchange System)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-17-320.jpg)

![18 CHAPTER 2. CRYPTOGRAPHIC PROTOCOLS

2.1.3 Narrations

Though in the Avispa and Avantssar we have worked on the definition of more

complex protocol specification languages, the specification of a protocol by a

single sequence of messages as in [98, 148, 126, 162] is sufficient for most cryp-

tographic protocols even though the internal computations of the agents is not

specified. In its simplest form, a narration is a sequence of message exchanges

followed by the initial knowledge each participant must have to engage in the

protocol (Needham-Schroeder Public Key protocol, [166]):

A→B:encp ( A, Na , KB )

B→A:encp ( Na , Nb , KA )

A→B:encp (Nb , KB )

where

−1

A knows A, B, KA , KB , KA

−1

B knows A, B, KA , KB , KB

The names A and B in this sequence do not refer to any particular individual

but to roles in the narration: common names instead of A and B are Client,

Server, Initiator,. . . Actual participants in an instance (also called session) of

the protocol play each one of the roles defined by the message exchange.

We note that the messages Na and Nb are not in the knowledge of A nor

of B. These are nonces, i.e. random values created at the beginning of each

instance of the protocol.

Personal work:

We present in Chapter 6 how these narrations can be given an operational

semantics. The languages we have developed in the course of the Avispa

and Avantssar projects did not need such developments given that the

modeler of a protocol in HSPSL [64] or ASLan V.2 has to specify also

the internal actions of the roles. Though it is often tedious to write such

specifications, the language aims at a greater accuracy of the protocol

model. We note that latest works such as [163] step back on this choice

and return to simpler models.

2.1.4 Security Properties

Generally speaking [83] one can distinguish two kinds of properties for programs

such as protocols:

• Properties that are defined by a set of possible executions of the protocol;

• Hyper-properties that are defined by the set of the sets of possible execu-

tions of the protocol.

Our work principally focuses on the properties of protocols such as:

• Secrecy, i.e. determining whether one of the messages exchanged can be

constructed by an attacker;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-18-320.jpg)

![2.1. CRYPTOGRAPHIC PROTOCOLS 19

• Authentication, i.e. determining whether the principals accept only the

messages originating from the participants listed in the narration.

Example 1. The simplified [147] version of the Needham-Schroeder Public Key

protocol (NSPK) [166] exhibits vulnerabilities to both secrecy and authentica-

tion. Whereas at the end of their respective execution A and B shall be assured

to have engaged in a conversation one with another and that the nonces Na and

Nb are kept secret, Lowe [147] found the following attack:

A → I :encp ( A, Na , KI )

I(A)→ B :encp ( A, Na , KB )

B →I(A):encp ( Na , Nb , KA )

I → A :encp ( Na , Nb , KA )

A → I :encp (Nb , KI )

I(A)→ B :encp (Nb , KB )

In this attack A starts a legitimate instance of the protocol with an intruder, i.e.

a dishonest agent I. This intruder then masquerades as A—the corresponding

events are denoted I(A)—and initiates a session with B. B responds as if he

were talking to A, and ends successfully his part of the protocol. However, in

the course of his protocol instance B has accepted messages issued by I instead

of A, hence an authenticity failure. Furthermore, the nonces Na and Nb , which

are believed by B to be a common secret shared with A, are actually known by

I, hence a secrecy breach.

Personal work:

Until recently I have worked only on the security analysis of properties

such as secrecy and authentication. However in a debuting series of work

I also consider the problem of the security analysis w.r.t. the equivalence

of protocols. This notion is employed to reason about anonymity, e-voting

protocols, abstraction of a perfect primitive by a concrete one, and so on.

Chapter 10 includes these results, which are related to the refutation of

cryptographic protocols.

2.1.5 Formal methods

We have worked on the formal analysis of cryptographic protocols. This means

that given a specification such as a narration we built a logical model of the

protocol and its environment consisting in three parts describing respectively:

• the possible actions of agents behaving as prescribed by the roles in the

protocol;

• the possible actions of an attacker in the setting considered;

• the property we want to verify.

The parallel execution of roles and of the intruder is interpreted by a conjunc-

tion. Two types of logical analysis can then be performed:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-19-320.jpg)

![20 CHAPTER 2. CRYPTOGRAPHIC PROTOCOLS

Validation: one proves that the property is logically implied by the specifica-

tions of the protocol and of the intruder;

Refutation: one constrains the logical specifications e.g. by imposing an ini-

tial state, bounds the number of possible instances of the protocol,. . . and

proves that under these restrictions the property is not logically implied

by the specifications of the protocol and of the intruder.

When failing in refuting a protocol, we can only conclude that under the con-

straints imposed there is no attack. Of course this does not mean that there is

no attack when weaker constraints, or none, are imposed. Let us review some

of the constraints routinely imposed:

Isolation: no protocol is executed concurrently with the one under scrutiny.

While unrealistic, this assumption, or some weaker version of it, is needed

given that for any protocol P one can construct a protocol P’ [132] such

that, when P’ is executed concurrently with P the attacker can discover

a secret message exchanged in P. While this result is theoretical as the

second protocol has to be constructed from the first one, such attacks also

often occur in practice [91].

In [50, 19] the isolation assumption is weakened into assuming, in some

form or another, that no other protocol executed concurrently uses the

same cryptographic data. Concerning symbolic analysis of protocols, one

can find in [163] similar assumptions employed to obtain the soundness

of the composition of transport protocols. Other similar conditions for

the sequential or parallel composability can also be found in [10, 88] and

others that can be traced back to the non-unifiability condition initially

introduced for the decidability of secrecy in [185].

Soundness: the properties of cryptographic primitives are usually [119, 115,

184] expressed by games in which an intruder, modeled by a probabilistic

Turing machine, cannot in a reasonable amount of time have a significant

gain over a toss of coin. For instance in IND-CPA games the intruder is

given a public key. He then chooses two messages m0 and m1 , and is then

presented with the encryption of either m0 or m1 . He wins the game if he

can choose m0 and m1 such that he has strictly2 more than 50% chances

of guessing the right answer.

While there are some attempts [23, 24] to directly interpret the construc-

tions on messages in terms of probability distributions, the usual lifting

of these properties into a symbolic world is problematic given that they

express what the intruder cannot do, whereas the symbolic analysis rests

on the description of what the intruder can do. We present how the trans-

lation from the concrete cryptographic setting to the symbolic world can

be justified in Subsection 2.2.2.

2 The actual condition is actually even more restrictive, and depends on the length of the

key](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-20-320.jpg)

![2.2. VALIDATION OF CRYPTOGRAPHIC PROTOCOLS 21

Bounds on the instances of the protocol: though in practice the number

of distinct agents that can engage in an unbounded number of sessions of a

cryptographic protocol is a priori unbounded, it has been proved [85] that

if there is a secrecy (resp. authentication) failure in an arbitrary (w.r.t. the

number of sessions and the agents participating in each session) instance

of the protocol then there is a secrecy (resp. authentication) failure with

the same number of sessions but only 1 (resp. 2) distinct honest agents,

in addition to the intruder, instantiating the roles of the protocol.

Furthermore Stoller [200, 201] remarked that essentially all “standard”

protocols either had a flaw found when examining a couple of sessions

or were safe. While this cannot be argued for cryptographic protocols in

general [160] this remark lead to the refutation-based methods in which

one only tries to find an attack involving a couple of distinct instances

of the protocol. We present more in details in Section 2.3 the history of

refutation with a bounded number of instances of the protocol.

2.2 Validation of Cryptographic Protocols

2.2.1 Validation in a symbolic model

Validation of cryptographic protocols is usually performed under the assumption

that the protocol is executed in isolation, this assumption being justified by the

work on the soundness w.r.t. the concrete cryptographic setting described in

Section 2.2.2. Under this isolation hypothesis, validation of a protocol amounts

to proving that for any number of parallel instances of the protocol, each instance

provides the guarantees claimed by the protocol. This problem is usually treated

by translating the descriptions of the intruder and of the honest agents into sets

of (usually Horn) clauses, and by reducing the problem of the existence of an

attack to a satisfiability problem.

This approach is successful in practice, see for example the ProVerif tool

by B. Blanchet [38], and some decision procedures were also obtained. The

satisfiability of sets of clauses in which each clause either has at most one variable

or one function symbol is decidable [84], a NEXPTIME bound is given in [194,

195]. This problem is DEXPTIME-complete if all the clauses are furthermore

Horn clauses. The class of sets of clauses was later extended to take into account

blind copy [90] while preserving decidability.

It was also extended to take into account the properties of an exclusive

or [196]. While in this article it is also proven that adding an abelian group ad-

dition operation leads to undecidability, it was implemented in ProVerif in [137],

and the decidability of some particular case, including some group protocols,

was proven.

2.2.2 Soundness w.r.t. a concrete model

Validation of a cryptographic protocol is done w.r.t. a given attacker model.

However there is no assurance that the modeled attacker is as strong as an at-

tacker who can take advantage of the precise arithmetic relations between the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-21-320.jpg)

![22 CHAPTER 2. CRYPTOGRAPHIC PROTOCOLS

messages, the keys, and so on. For example the Pollard ρ method [182] is based

on the computation of collisions (different products having the same result) in

a finite group and speeds-up significantly the factorization of some integers. We

thus have a discrepancy between the symbolic analysis of cryptographic primi-

tives, which is conducted independently from the actual values of the messages

exchanged and the keys, and the analysis in the concrete setting in which the

attacker has access to the actual values of the messages and the keys, with

this additional information opening the possibility of additional attacks on a

protocol.

There has been a lot of work trying to relate concrete settings to symbolic

ones, starting with [177]. As demonstrated by e.g. [50] finding a good setting is a

difficult and error-prone task. However more recent works such as [19, 138, 139]

have provided sound and usable definitions and cryptographic settings. If one

agrees on the restriction on the usage of cryptographic protocols and of keys

imposed by these settings there exists a cryptographic library that hides the

concrete values of the keys by imposing the use of pointers instead of real data

and such that every useful manipulation on message can be performed by calls

to this library.

2.3 Refutation of Cryptographic Protocols

2.3.1 Advantages over validation

Validation of cryptographic protocols is undecidable even in the simplest settings

in which perfect cryptography is employed, the protocol is executed in isolation

from other protocols, and either only a finite number of distinct values are

exchanged or some typing systems ensures that the complexity of the messages

is bounded. Furthermore the soundness of a validation procedure is hard to

establish: though one can prove that in a given symbolic model there is no

attack on a protocol, this result does not necessarily translate into the validation

of a concrete version of the protocol as was described in 2.2.2.

However, when trying to refute a protocol, the translation to the concrete

level is simpler as it suffices to prove that any action performed by the attacker

in the symbolic model can be translated into an action of an attacker in the

concrete model. Also the restrictions imposed on the protocols to ensure the

decidability of their validation are usually too strong for real-life case studies.

These reasons motivated the refutation of cryptographic protocols under

constraints: instead of trying to prove that a protocol is valid one tries to dis-

cover an attack when additional constraints on the protocol are imposed. In

accordance with the observations by Stoller [200, 201] the most common con-

straint consists in: a) bounding the number of messages the honest participants

can receive; and b) forcing the participant either to accept a message or aborts

his execution of the protocol. These assumptions can be translated in terms

of processes by imposing that the honest participants are modeled by processes

without loop and in which the “else” branch of the conditional is always an](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-22-320.jpg)

![2.3. REFUTATION OF CRYPTOGRAPHIC PROTOCOLS 23

abort. Usually one further imposes that the tests in the conditional must be

(conjunctions of) positive equality tests. Another common restriction consists

in bounding the complexity of the terms representing the messages.

Under these assumptions it is possible to devise decision procedures for the

refutation of cryptographic protocols w.r.t. a model of the attacker. When

conducting such an analysis one first has to provide the reader with a message

and deduction model, and then only can one present a decision procedure w.r.t.

these models. In more details we have:

Message model: Messages are modeled by first-order terms, i.e. finite recur-

sive structures defined by the applications of some functions on terms and

by constants. The first task in protocol refutation consists in defining the

properties of these functions. For instance one should model that a bitwise

exclusive-or operation ⊕ is commutative, i.e. for every messages x and y

the equality x ⊕ y = y ⊕ x holds;

Deduction model: Then one has to model how the attacker can use messages

at his disposal to create new ones. This is usually done by assuming

that the intruder can apply (a subset of) the symbols employed to define

the messages to construct new messages. For example an asymmetric

encryption algorithm can be employed by the intruder to construct new

messages, but the sk( ), pk( ) symbols, employed to denote the public and

private keys, cannot be employed by the intruder to construct new keys;

Decision procedure: Finally one searches a decision procedure applicable to

all finite message exchanges where the messages are as defined in the first

point when attacked by an intruder having the deduction power as defined

in the second point.

Since we attempt to refute protocols the soundness of the message and de-

duction models is more important than their completeness. Forgetting some

possible equalities or deductions may lead to inconclusive analysis (stating that

no attack is found under the current hypotheses), but having unsound equal-

ities or deductions could lead to false positives, i.e. a valid protocol could be

declared as flawed.

2.3.2 Personal Work on the Refutation of Cryptographic

Protocols

During my PhD I have worked on the refutation of cryptographic protocols

when the number of messages exchanged among the honest agents is bounded.

In collaboration with Laurent Vigneron, I first extended Amadio and Lugiez’s

decision procedure [8] to take into account the case of non-atomic secret keys

and implemented it in daTac [78]. Then we have presented an abstraction of

the parallel sessions of a cryptographic protocol [77, 79] in which it is possible

to validate strong authentication, in contrast with other existing abstractions

(e.g. [41]) in which replay attacks cannot be detected. This abstraction is based](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-23-320.jpg)

![24 CHAPTER 2. CRYPTOGRAPHIC PROTOCOLS

on a saturation of the protocol rules modeled as clauses, and on the extension of

the intruder’s deduction capacities with these so-called “oracle” rules, instead

of simply checking the property in the saturated set of rules. Then, and before

I finished my PhD, I have worked with R. K¨sters, M. Rusinowitch, and M. Tu-

u

ruani on the extension of the complexity result obtained in the case of perfect

cryptography [190, 144] to the cases in which an exclusive-or [68, 61], an expo-

nential for Diffie-Hellman [69, 62], commutative asymmetric encryption [60, 62],

or oracle rules [63] were added to the standard set of intruder deduction rules.

I finally presented a lazy constraint solving procedure [56] that extends the one

in [78] to protocols in which an exclusive-or symbol appears. This procedure

was implemented in CL-AtSe [208] by M. Turuani and M. T¨ngerthal with some

u

further optimization on the exclusive-or unification algorithm [207].

This serie of results was however non-satisfactory given that there was no

result on the decidability of refutation when e.g. both an exponential and an

exclusive-or appear in the protocol. In collaboration with M. Rusinowitch we

have considered the problem of the combination of decision procedures for refu-

tation, and presented a solution [70, 76] that reduces the refutation of protocols

expressed over the union of two disjoint sets of operators and with ordering re-

strictions to problems of refutation in individual signatures with the same kind

of ordering constraints. We later extended this result to well-moded but non-

disjoint union of signatures in [71, 72]. In [11] the authors build upon the first

combination result to obtain a similar one on the combination of static equiv-

alence decision procedures, while [157, 136] obtain similar conditions for the

combination on non-disjoint signatures, and [47] extends it to take into account

some specific properties of homomorphisms. Finally let me mention that the

well-moded constraint is rather general and intuitive, given that it was defined

to model the properties of exponential w.r.t. the abelian group of its exponents,

but was also employed in [97] to model the relationship between access control

and deductions on messages in PKCS#11.

When Mounira Kourjieh began her PhD under my supervision, we started

to work on a novel research direction. As explained above, the traditional

research on the relation between concrete and symbolic models of cryptographic

primitives is based on the establishment of a set of assumptions on the use of

these primitives and on the management of the keys, and in proving that under

these assumptions one can build a complete symbolic model such that, if there

is no flaw on the symbolic level then there is no flaw on the concrete level. We

remark that:

• the approach may be too restrictive for real-life protocols, as it requires

e.g. that the keys are created and managed by a trusted entity—the

cryptographic library;

• the soundness of validation in the symbolic model is hard to establish

given that one has to account for all the possible actions of the attackers.

This is in contrast with the soundness of refutation for which one only has

to prove that the actions described in the symbolic setting are feasible in

the concrete setting.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-24-320.jpg)

![2.3. REFUTATION OF CRYPTOGRAPHIC PROTOCOLS 25

For these two reasons we have tried to model the weaknesses of the cryptographic

primitives when no assumption is made on the keys creation and management:

instead of restricting the concrete level to make it fit a symbolic model we

have instead augmented the symbolic model to take into account the known

attacks on the concrete primitives. We have achieved decidability results for

signatures in the multi-user setting [58] and the decidability3 of the refutation

for hash functions for which it is feasible to compute collisions [57]. This work

is presented in more details in Chapter 8.

3 Under the assumption that the combination result of [71] on deduction systems also holds

on extended deduction systems.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-25-320.jpg)

![Chapter 3

Web Services

As a continuation of my work on cryptographic protocols I have

begun research on Web Services when I arrived in Toulouse

in 2004. While at first they were simply viewed as crypto-

graphic protocols exchanging XML messages, this very active

area turned out to be the source of a variety of research prob-

lems related to the modeling of the access control policy and

of the workflow of Business Processes. Also of interest is the

emerging development of modular methods for the validation of

Web Services. We introduce in this chapter Web Services with

a short historical introduction, followed by a description of the

aspects of concern to my research. I conclude it with a summary

of my research on this topic.

3.1 Web Services

3.1.1 Basic services

1

The usual characterization of Web Service defines a Web Service as an appli-

cation that communicates with remote clients using the HTTP [114] transport

protocol. The principle of having applications executed on a server computer

and used by remote clients is not an original one, as was already present in Sun’s

mid-90’s motto “Network is the computer”. However the first implementations

were impractical, for several reasons:

• Sun’s proposal was to code all the applications in Java to ensure inter-

operability.

• The Corba2 framework aimed at the independence from Java, but suffered

from the choice of a binary encoding of data (which implies the difficulty

1 This historical discussion is based, among other sources, on http://www.ibm.com/

developerworks/webservices/library/ws-arc3/.

2 Common Object Request Broker Architecture.

27](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-27-320.jpg)

![28 CHAPTER 3. WEB SERVICES

for different vendors to provide interoperable solutions) and of a dedicated

transport protocol called IIOP [159] that imposes constraints on the pro-

grammer and limits interoperability to platforms understanding it;

These limitations have not prevented both Java and Corba to be successful

in a closed environment, but were too strong for the overall adoption of these

solutions for client/server communications.

Given the workforce needed to specify, standardize, and implement inter-

operatively a protocol on a variety of platform, a natural choice for the transport

protocol was to rely on an off-the-shelf widely implemented protocol. HTTP

stood out among other possibilities because a) it is an open protocol, and

b) client interfaces are already provided by existing Web browsers, and c) these

Web browsers also already support scripting languages, and d) its traffic is in

most cases not blocked by firewalls. Furthermore, when employed in combina-

tion with the TLS [102, 103] protocol it provides the basic security guarantees

of server authentication and confidentiality. One usually differentiate between

SOAP and REST Web Services. The former are based on SOAP, an application-

level transport protocol that relies on post/get HTTP verbs. In addition to

these verbs the REST Web Services also use the update/delete ones, but do

not need the extra abstraction provided by the SOAP protocol.

Another characterization of Web Services (starting from WSDL 2.0 [187]) is

the description of an available service in the Web Service Description Language.

This is a language in which the individual functionalities, called operations, are

advertised together with a description of their in- and output messages, as well

as a description of how one can connect to the service. An important point

is that for Web Services described in WSDL, HTTP is not the only possible

transport protocol. Originally WSDL [81] was designed to describe Web Services

communicating using the SOAP [120] protocol, an application-level protocol

originally running on top of HTTP. Bindings of SOAP to other protocols such

as JMS or smtp have since been defined, and with WSDL 2.0 the application-

level transport protocol is not necessarily SOAP anymore.

Example 2. The Amazon S33 (Simple Storage Service) provides users with a

storage space as well as with operations enabling the user to set an access control

policy to her files and add, view, remove files from the store. It is available both

in the REST style and in the SOAP style.

Model. In the rest of this document we consider an abstraction of Web Ser-

vices in which the exact transport protocol employed is irrelevant, assuming

that one could describe more precisely the messages whenever one wants to

consider the exact binding employed. As a result, a Web Service is akin to a

role specification in which request/response pairs of messages are defined, but

without necessarily constraints on the order in which the requests are received.

3 API description available at url http://docs.amazonwebservices.com/AmazonS3/latest/

API/.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-28-320.jpg)

![3.1. WEB SERVICES 29

3.1.2 Software as a Service

WSDL defines which functionalities a service offers as well as how one com-

municates with the service. However, since their inception, Web services have

gradually turned from remotely accessible libraries to full-fledged applications.

The general idea is to transform existing applications, or create new ones, by

writing independent software components and by establishing communication

sequences between these components. The goal is to:

• ease the deployment of new applications and the development of new com-

ponents;

• ease the changes in an application by containing each one in a single

component;

• rely on the fact that each component is remotely accessible to gain flexi-

bility on the hardware infrastructure, i.e. the actual computers running

the components, for example by relying on a Web server to dispatch a

request to the computer on which the application is deployed.

The separation into atomic components necessitates a way to glue these com-

ponents into applications. This glue is called a business process, and is written

in a language in which, besides the usual assignments, conditionals, and loops

constructs, there exists basic constructs to invoke a remote service. Some of

these languages are scripting languages such as python or Ruby, but we have

chosen to focus on BPEL [128] Business Process Execution Language because

of its natural integration in the WSDL description of a service: services in-

voked are referenced using their WSDL description, and the process itself can

be advertised by publishing a WSDL description of it.

A current trend is also to employ Web Services to outsource the computers in

which a corporation’s applications are executed. I.e. the services are not hosted

on a computer belonging to the corporation but on computers provided by a

third party, who in returns perceives some payment according to the resources

used by the applications. A merit of this cloud computing approach is the

low initial cost of deployment of services as well as the reduced uncertainty

on the running cost/customer ratio, a crucial benefit in nowadays economic

environment.

Model. When analyzing the security of a Web Service, we simply model Busi-

ness Processes with an ordering on the possible input and output messages. But

when considering the access control policy of services we introduce a process de-

scription language which is a simplified version of BPEL, see Chapter 7.

3.1.3 Security Policies

In general terms, a policy controls the possible invocation of the operations of

a service, such as its Quality of Service, or its business logic. In a framework

such as JBOSS, even the business process can be encoded as a policy over the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-29-320.jpg)

![30 CHAPTER 3. WEB SERVICES

acceptable requests. Instead of analyzing policies in general, we focus on two

types of security-related policies:

• the message-level security policy, which expresses how the data transmit-

ted to and from the service has to be cryptographically secured;

• the access control policy, which is expressed at the level of the application

and expresses when an invocation is legitimate.

Message Protection

There are two main ways to secure the communications of a service with its

partners: a) to impose that the transport protocol must be secured, and b) to

impose the usage of cryptographic primitives to protect the sensitive parts of

the transmitted messages.

Given that there exists secure transport protocols such as TLS, one could

wonder why one would need to further protect the messages. The main moti-

vation for this extra protection is the fact that the protection provided by TLS

is a point-to-point one, whereas complex service interactions depend upon end-

to-end security. A simple example would be the payment of an item purchased

on Internet. One does not necessarily trust the e-commerce web site enough to

send it one’s credit card information, even though they have to be transmitted

to the bank to complete the transaction. Thus the client has to send to the

e-commerce web site her credit card information cryptographically protected in

such a way that: a) this web site will be able to employ the protected data to

complete the transaction with the bank, but also b) this web site will not be

able to derive the credit information from the data. Other applications include

digital contract signing, electronics bidding, etc.

Model. Cryptographically protected messages are simply cryptographic pro-

tocol messages. When analyzing access control policies, which rely on the pay-

load of messages rather than on the cryptography employed to secure the mes-

sages, we partially abstract the message layer by simply assuming that the

payload is either signed, encrypted, or both, or none, by a user and that the

transport protocol is either secured or not. See Chapter 7.

Authentication–Assertion–Authorization

Access control consists in determining whether a given entity has the right,

under the actual known circumstances, to perform a given action on a protected

object. Access control rules emit opinions on whether the access should be

granted or denied, and an access control policy gathers these opinions and uses

a policy combination algorithm to grant or deny the access to the resource. A

rule is said to be applicable on a request if it emits a grant or deny opinion.

In the most simple form rules are totally ordered, and the opinion of the first

applicable rule is the resulting opinion of the set of rules, but other combinations

algorithms can be found e.g. in [173].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-30-320.jpg)

![3.1. WEB SERVICES 31

Expressibility. Just as Object Oriented programming simplifies the manage-

ment of objects by organizing them in a hierarchy, a lot of research on access

control is focused on the simplest ways to write rules that are both sound w.r.t.

desired policies and easily writable and understandable. In this line we note

the RBAC (Role Based Access Control ) framework proposed by Ferraiolo and

Kuhn [113] that organizes individuals according to the administrative role they

have (doctor, visitor, etc.) together with a role hierarchy that defines the inher-

itance of permissions of junior role r to a senior role r . Access control decisions

are based uniquely on the role played by the requester, on the action, and on

the object in the request. OrBAC [129] refines this model by introducing a hi-

erarchy of contexts in which a request has to be analyzed as well as a hierarchy

on objects. These models often yield very simple policies but at the expense of

expressibility. For example in pure RBAC it is not possible to express that the

same individual, regardless of her role, shall not perform two different actions in

the same execution context (this is called dynamic separation of duty). On the

other side of the spectrum, ABAC (Attribute-Based Access Control ) provides

no hierarchy, and the decision is based solely on the values of a set of attributes

extracted from the request and from the environment. This implies that every

aspect that can influence an access control decision has to be modeled by a

valued attribute, and thus that this type of access control system, while being

able to express any kind of policy, is hard to deploy and manage. Its versa-

tility nonetheless made it the system of choice for Web Service access control

systems such as XACML [173], especially in the currently developed XACML

3.0 version, with its WS profile [9].

Layered model of Access Control. A layered model has emerged over the

years from the industry best practices as well as from the availability of dedicated

systems. Access control in distributed systems is now viewed as consisting in

three interacting components:

Authentication: the first phase is implemented in applications such as Shib-

boleth and consists in the authentication of users. I.e., a user has to

authenticate to one such server using e.g. his login and password or a

more complex authentication protocol, and once the authentication con-

straints imposed on the server are satisfied (e.g. the user has provided a

valid certificate authenticating his signature verification key and has re-

sponded successfully to a challenge-response protocol) the server issues

a token that can be employed by the user to prove his identity to other

services. Alternatively, in the case of SAML Single Sign-On, the server

will authenticate the user to other services.

Assertions: once the user is identified he can negotiate with security services to

obtain assertions that qualify him. For example a user can use his identity

to activate a role and thereby obtain a role membership credential. This

credential can then be employed to gain new ones expressing permissions

associated with this role.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-31-320.jpg)

![32 CHAPTER 3. WEB SERVICES

Authorization: Finally, when trying to execute an action on a resource, the

user decorates his request with the necessary credentials, and an autho-

rization decision is taken based on the value and origin of the provided

attributes.

Model. Given that we are less interested in a user-friendly access control

system than in the analysis of the access control policy of a set of Web Services

we have adopted a formal model of attribute-based access control. We have

abstracted away the authentication phase by using secure channels providing

authentication, and are left with the modeling of the assertion collection part

and of the authorization part of access control. We present in Chapter 7 a

comprehensive model of a distributed access control system for Web Services

where the rules are furthermore modeled as Horn clauses.

3.2 Results achieved in the domain of Web Ser-

vices

I have collaborated with Marwa El Houri, a PhD student I supervised, and

Philippe Balbiani on the definition of a formal model for the analysis of Web

Services [110]. Our final proposal consists in modeling each component in a

Web Service infrastructure by a communicating entity, i.e. an agent that has:

• a store that permits to model a memory, a database, the history of the

service, etc.;

• a trust negotiation policy that indicates which credentials the entity is

ready to share with which other entities on which kind of channel;

• A workflow which consists in a set of tasks. Tasks are recursively defined,

and an authorization rule controls each invocation of a task.

Given the part of an infrastructure (a database system, a human agent, a trust

negotiation engine or a Business Process Engine) modeled by an entity some of

the above parts may be empty.

This model permits us to seamlessly encode Role Based Access Control with

(dynamic) separation or binding of duties constraints as well as advanced fea-

tures such as all surveyed kinds of delegation [110]. We have also enriched it

with cryptographic primitives and secure channels to enable the validation of a

given set of entities w.r.t. untrusted users [110].

In collaboration with Mohammed Anis Mekki—a PhD student I co-supervise

with M. Rusinowitch—and M. Rusinowitch we have considered the choreogra-

phy problem for a set of services. This problem consists in building, given a

finite set of available services, an orchestrator that communicates with these

services to achieve a given goal. I detail this work in Chapter 9. Also presented

in that chapter is the work in collaboration with Tigran Avanesov, M. Rusi-

nowitch and Mathieu Turuani on the choreography problem for services which](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-32-320.jpg)

![Chapter 4

Fundamentals of

First-Order Logic

We introduce in this chapter the formalism and notions that will

be employed in the rest of this document. This chapter is aimed

at presenting first-order logic with an emphasis on resolution,

and should be read as a basis for a course on first-order logic ori-

ented towards resolution and its applications. This focus means

that significant though unrelated notions are lacking. The in-

terested reader can find in particular complements on sequent

calculus and semantic tableaux in [94].

This chapter ends with the definition of equational theories, a

more advanced concept that we need to analyze cryptographic

protocols. In particular we extend the unification notions intro-

duced together with resolution to unification modulo an equa-

tional theory. We also prove a few important facts on equational

unification.

4.1 Facts, sentences, and truth

4.1.1 Reasoning on facts

Consider the following sentences:

• It is summer or the temperature is cold;

• It is not summer or the weather is rainy.

We rely on the excluded-middle law 1 which states that a fact can only be true or

false. As a consequence we can reason on the possible truth value of the fact “It

1 In Scottish courts the result of a criminal prosecution can be either proven (meaning

guilty), not proven, or not guilty. In this case we can have at the same time that the result

of the prosecution is not “proven” and is not “not proven”. Beyond the anecdote logic with

no excluded-middle law (intuitionistic logic, linear logic, . . . ) have been employed fruitfully

37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-37-320.jpg)

![38 CHAPTER 4. FUNDAMENTALS OF FIRST-ORDER LOGIC

is summer”. If it is true then the fact “It is not summer” must be false. Since

the second sentence is true one can deduce that the weather is rainy. But it may

also be the case that the fact “It is summer” is false. Since the first sentence is

true we must then have that the temperature is cold. As a conclusion of these

two sentences, either the temperature is cold or the weather is rainy.

Generally speaking, if A, B1 , . . . , Bn , C1 , . . . , Ck are facts, and the sentences:

• A or B1 or . . . or Bn ;

• not(A) or C1 or . . . or Ck .

are true, then if A is true, not(A) must be false, and thus C1 or . . . or Ck is

true since the second sentence is. Symmetrically if A is false we must have B1

or . . . or Bn because the first sentence is true. This reasoning is sound since if

the assumptions are true then the conclusion must be true.

This reasoning can also be conducted if there is no alternative in one of the

sentences. Assume the following two sentences are true:

• It is day or it is night;

• It is not day.

One ought to conclude that it is night. Another special case is when there is no

alternative in both sentences. For instance assume the following two sentences

are true:

• It is day;

• It is not day.

By following the general scheme given above we deduce that a sentence with

no facts must be true. But the common sense also tells us that the assumption

that both sentences are true does not hold: a fact and its negation cannot be

both true. We reconcile these two conclusions by imposing that a sentence

with no facts must always be false, and rely on the soundness of our deduction

mechanism to deduce (by contrapositive reasoning) that if the conclusion is

false then one of the premises must be false. In this case, i.e. when in a set of

sentences at least one must be false whatever truth value is chosen on the facts,

we say that this set is inconsistent.

The case-based reasoning on sentences illustrated above is called resolution.

It was introduced by Robinson [3] as a reasoning mechanism for the whole of

first-order logic, in which one can e.g. axiomatize Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory.

Outline of this chapter. We begin this chapter with a section on orders,

and review some definitions and properties. Then we define in Section 4.3 the

language employed to describe sentences. We give a semantics to first-order

to reason about the existence of a proof of a theorem, a proof of the negation of a theorem,

and the absence of proof for both a theorem and its negation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-38-320.jpg)

![44 CHAPTER 4. FUNDAMENTALS OF FIRST-ORDER LOGIC

• a (β, α)-atom is a (β, α)-formula;

• if f1 , f2 are (β, α)-formulas then f1 ∨ f2 and f1 ∧ f2 are (β, α)-formulas;

• if f is a (β, α)-formula then ¬f is a (β, α)-formula.

Example 5. Continuing the examples 3 and 4 a formula is an expression like:

¬(inf(abs(minus(x, x )), λ)) ∨ inf(abs(minus(f (x), f (x ))), ε)

Given a formula ϕ where the atoms a1 , . . . , an occur we denote Var(ϕ) (resp.

Const(ϕ)) the set ∪n Var(ai ) (resp. ∪n Const(ai )).

i=1 i=1

4.3.5 Quantifiers

The definition of (β, α)-formulas is still ambiguous. When one writes a(x) ∨ b(x)

it is not clear one means that for some value c of x it is true that a(c) ∨ b(c),

or one means that whatever the value c of x is it is true that a(c) ∨ b(c). In

order to precise the meaning of the variables in the formulas one introduces

existential (for some value of) and universal (for all values of) quantifiers denoted

respectively ∃ and ∀. Formally,

• A (β, α)-formula is a (β, α)-quantified formula with an empty set of quan-

tified variable;

• If ϕ is a (β, α)-quantified formula with a set of quantified variables Q

and x ∈ Var(ϕ) Q then ∃xϕ is a (β, α)-quantified formula with a set of

quantified variables Q ∪ {x};

• If ϕ is a (β, α)-quantified formula with a set of quantified variables Q

and x ∈ Var(ϕ) Q then ∀xϕ is a (β, α)-quantified formula with a set of

quantified variables Q ∪ {x}.

A (β, α)-quantified formula in which every variable is quantified is called a

(β, α)-sentence. Note that in the traditional presentation of sentences in first-

order logic the quantifiers may be interleaved with the logical connectives. The

price of the added complexity (in terms of defining the semantics, the quantified

variables, the handling of variable names clash, etc.) is however paid for nothing:

any (β, α)-sentence in the standard setting is logically equivalent to a formula in

the simpler language described above. An equivalent formula can be effectively

computed by algorithms that rewrite sentences in prenex normal form (see [146,

151, 94], for example).

Example 6. We complete the formula in the preceding example by quantifying

the variables occurring in two different ways, thereby obtaining two different

sentences:

∀x∀ε∃λ∀x , ¬(inf(abs(minus(x, x )), λ)) ∨ inf(abs(minus(f (x), f (x ))), ε)

∀ε∃λ∀x∀x , ¬(inf(abs(minus(x, x )), λ)) ∨ inf(abs(minus(f (x), f (x ))), ε)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-44-320.jpg)

![4.4. SEMANTICS OF FIRST-ORDER LOGIC 45

The educated reader should by now have noticed that we have given the usual

definitions of continuity and uniform continuity in a normed space. We leave as

an exercise the determination of an arrangement of quantifiers expressing that

the function f is a) bounded, or b) constant.

4.4 Semantics of First-Order Logic

4.4.1 Interpretation

Giving a semantics to a logic means defining when a formula is true. Since the

meaning of quantifiers and logical connectives is fixed, it suffices to define when

an atom is true. This is achieved by interpreting the symbols occurring in a

formula.

Definition 3. (Interpretation) Let α (resp. β) be a functional (resp. relational)

signature, and X be a set of variables. A (α, β)-interpretation I is defined by2 :

• A non-empty set DI , called the domain of the interpretation;

β(p)

• For each predicate symbol p in the domain of β a function I(p) : DI →

{ , ⊥};

α(f )

• For each function symbol f in the domain of α a function I(f ) : DI →

DI .

Given an interpretation I of domain DI a valuation v is a mapping from the

set of variables to elements in DI . Valuations are extended homomorphically

on terms, atoms, and formulas as expected.

The truth value of a sentence ϕ in an interpretation I of domain DI is

denoted [[ϕ]]I is determined as follows:

• If ϕ = ∃xψ(x) then [[ϕ]]I = if, and only if, there exists a valuation v of

domain x such that [[v(ψ(x))]]I = ;

• If ϕ = ∀xψ(x) then [[ϕ]]I = if, and only if, for all c ∈ DI we have

[[vc (ψ(x))]]I = with vc is the valuation mapping x to c;

• If ϕ = ϕ1 ∧ ϕ2 then [[ϕ]]I is if, and only if, [[ϕ1 ]]I = and [[ϕ2 ]]I = ;

• If ϕ = ϕ1 ∨ ϕ2 then [[ϕ]]I = if, and only if, [[ϕ1 ]]I = or [[ϕ2 ]]I = ;

• If ϕ = ¬ϕ1 then [[ϕ]]I = if, and only if, [[ϕ1 ]]I = ⊥;

• If ϕ = p(t1 , . . . , tn ) then [[ϕ]]I = I(p)(I(t1 ), . . . , I(tn ));

2 We note that the interpretation of a variable is not defined. While usually interpretations

are extended over variables with valuations—functions mapping variables in the formula to

elements in the domain of the interpretation—we have chosen to instantiate in the formulas the

variables by the elements of the domain. Given that this interleaving is not defined formally,

this instantiation should be thought of as syntactic sugar.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-45-320.jpg)

![46 CHAPTER 4. FUNDAMENTALS OF FIRST-ORDER LOGIC

• Given a valuation v we have [[x]]I = v(x) if x is a variable. Otherwise we

must have t = f (t1 , . . . , tn ), and we define [[t]]I = I(f )([[t1 ]]I , . . . , [[tn ]]I ).

Note that since all the variables in a sentence are bound by a quantifier and

all quantifiers appear first every variable in the formula is in the domain of a

valuation when evaluating an atom. An interpretation that makes a sentence

true is called a model of this sentence.

Definition 4. (Model) Let ϕ be a first-order sentence and I be an interpretation

with [[ϕ]]I = . We say that I is a model of ϕ, and denote I |= ϕ.

Given two formulas ϕ and ψ we also denote ϕ |= ψ the fact that for every

model I of ϕ we have I |= ψ.

Example 7. For instance, consider the following exercise:

Prove that the function f : I → I defined by f : x →

R R

x2 is continuous.

As it was already noted the first formula of Example 6 is the definition of

continuity if one considers the interpretation I:

• with a domain I

R;

• I(inf) =<, the usual order on I

R;

• I(abs) = x → |x|, the function that associates to an element of I its

R

absolute value;

• I(minus) = (x, y) → x − y, the usual subtraction in I

R.

This interpretation is not complete as it lacks the interpretation of the function

symbol f . This last part is contained in the statement of the exercise, with

I(f ) = x → x2 .

4.4.2 Satisfiability, validity

It is clear that the truth of a formula depends on the chosen interpretation. For

instance the first (resp. second) formula of Example 6 is true in the interpre-

tation I of Example 7 if, and only if, f is interpreted by a continuous (resp.

uniformly continuous) function. The goal of automated reasoning techniques

for first-order logic is to decide, given a sentence ϕ, whether:

• there exists at least one interpretation in which ϕ is true;

• or if for all interpretations ϕ is true.

In the former case we say the sentence is satisfiable, and in the latter case that

it is valid.

Definition 5. (Satisfiability, validity) A sentence ϕ is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-46-320.jpg)

![4.5. FOUNDATIONS OF RESOLUTION 47

• satisfiable if there exists one interpretation in which ϕ is true;

• valid if it is true in any interpretation.

Example 8. The definition of continuity is certainly satisfiable since it is true

in every interpretation I in which I(f ) is a continuous function, but is not valid

since it will be false if one interprets f with a non-continuous function.

For the sake of completeness we also say that a sentence is unsatisfiable if

it is not satisfiable—i.e. is false in every interpretation—, and falsifiable if it is

not valid—i.e. is false in some interpretation.

Logical equivalence. Let us now define the notion of logical equivalence that

we have employed in Section 4.3.5 when stating that every first-order sentence

in which the quantifiers are scattered in the formula, such as ∀x((∃yp(x, y)) ∨

(∀zp(y, z))) is logically equivalent to a sentence in which all the quantifiers ap-

pear in sequence at the beginning of the formula, e.g. ∀x∃y∀z(p(x, y) ∨ p(y, z)).

Definition 6. (Logical equivalence) Two first-order logic sentences ϕ and ψ

are logically equivalent if, and only if, for every interpretation I we have:

[[ϕ]]I = [[ψ]]I

4.5 Foundations of Resolution

The logical equivalence between two first-order sentences means that they have

exactly the same set of models. However as long as one is concerned with sat-

isfiability or validity (by considering the negation of the formula), the relevant

notion is the one of having or not a model. A second equivalence between

first-order sentences, called equisatisfiability, reflects this importance. Two for-

mulas ϕ and ψ are equisatisfiable when ϕ is satisfiable if, and only if, ψ is

satisfiable. This equivalence relation is very coarse since it defines only two

equivalence classes. It is however very useful when considering algorithms that

have to decide whether a given formula is satisfiable. Indeed, this notion al-

lows such algorithms to transform sentences into non-logically equivalent one as

long as the transformations performed change a sentence into an equisatisfiable

one. In particular skolemization first brick of automated reasoning techniques

in first-order logic—transforms any first-order sentence into an equisatisfiable

first-order sentence with no existential quantification. We then prove that when

considering their satisfiability it suffices to interpret these sets of universally

quantified clauses in Herbrand’s interpretations, i.e. interpretations that equal-

ize the functions in the domain with the function symbols in the formula. Then

we prove that to prove the unsatisfiability of a finite set of clauses it suffices to

prove the unsatisfiability of a finite set of instances of these clauses.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-47-320.jpg)

![4.5. FOUNDATIONS OF RESOLUTION 49

domain D as I, equal to I on the symbols in the domains of the signatures α

and β, and such that I (f ) = f I . By construction I is a model of ϕ .

⇐ Let I be a model of ϕ , and let f I = I (f ). By definition every

occurrence of f in ϕ is in the term f (x1 , . . . , xn ). Thus there exists in D an

element b = f (a1 , . . . , an ) such that in ϕ(a1 , . . . , an , b) evaluates to in I .

Thus I’ is an interpretation that satisfies ϕ.

The skolemization lemma can be iterated on a sentence to remove every

existential quantifier from the left to the right. Since each iteration transforms

a sentence into an equisatisfiable one we obtain the following theorem.

Theorem 4.1. (Skolem, [198]) Every first-order sentence ϕ is equivalent with

respect to satisfiability to a universally quantified sentence.

Since the variables in a universally quantified sentence are all bound by

the same quantifier we will often, in the rest of this document and when this

introduces no ambiguity, write sentences without the quantifiers.

4.5.2 Clauses

The logical connectives we have employed to relate the atoms one with another

in a formula share some properties known as de Morgan laws. Among these we

note especially the following ones:

Laws that move the negation down:

¬ ∧ ¬ ∨

∨ ≡ ¬ ¬ ∧ ≡ ¬ ¬

a b a b a b a b

Laws that move the disjunction down:

∨ ∧ ∨ ∧

a ∧ ≡ ∨ ∨ ∧ a ≡ ∨ ∨

b c a b a c b c b a c a

It is clear that using these laws and the fact that ¬¬x ≡ x it is possible to:

• First push the negation downward so that a formula is written as disjunc-

tions and conjunctions of atoms or negation of atoms. We call literals the

formulas that are either atoms or the negation of an atom;

• Then push the disjunction downward, resulting in a formula which is a

conjunction of disjunctions of literals.

In order to complete our transformation of sentences we need another lemma

that permits us to push quantifications downwards.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-49-320.jpg)

![50 CHAPTER 4. FUNDAMENTALS OF FIRST-ORDER LOGIC

Lemma 4.3. The formulas ∀x(ϕ(x) ∧ ψ(x)) and (∀xϕ(x)) ∧ (∀xψ(x)) are logi-

cally equivalent.

Proof. We prove only that every model of ∀x(ϕ(x)∧ψ(x)) is a model of (∀xϕ(x))∧

(∀xψ(x)), the converse being similar.

Let I be a model of ∀x(ϕ(x) ∧ ψ(x)) with a domain D = ∅. By definition for

all a ∈ D we have [[ϕ(a) ∧ ψ(a)]]I = , and thus by definition of the evaluation

of ∧, for all a ∈ D we have [[ϕ(a)]]I = and [[ψ(a)]]I = . Thus,

• For every a ∈ D we have [[ψ(a)]]I = , and thus I |= ∀xψ(x);

• For every a ∈ D we have [[ϕ(a)]]I = , and thus I |= ∀xϕ(x);

Thus by definition of the evaluation of the ∧ connective we have I |= (∀xψ(x))∧

(∀xϕ(x)).

We are now ready to sum up the transformations applied. First, we define

a clause as a universally quantified disjunction of literals, i.e. a formula of the

type:

∀x1 , . . . , ∀xn , l1 ∨ . . . ∨ lk

were each literal li is either an atom p(t1 , . . . , tm ) or its negation ¬p(t1 , . . . , tm ).

Defining a first-order theory as a conjunction of clauses, the transformations

described in this section imply the following theorem. Given that a theory is

always a conjunction of clauses it is also viewed as a finite set of clauses.

Theorem 4.2. Every first-order sentence can be effectively transformed into an

equisatisfiable first-order theory.

4.5.3 Herbrand’s theorem

We have seen that there are two distinct levels to first-order logic: a) the lan-

guage level in which formulas are defined; and b) the interpretation level in

which the symbols of a formula are interpreted as functions on a non-empty

domain. In order to avoid heavy notations we have already mixed both levels

when proving the correctness of skolemization, noting that it is possible to avoid

this interleaving of notations by completing the interpretation with an explicit

function that maps every variable to an element of the domain. The question

then arises as to whether one could go further and equate the symbols of the

language with those of the interpretation, or if a strict separation should be

kept.

To answer this question we first introduce a special domain, called the Her-

brand’s domain of a theory T , constructed as follows.

The functional signature of a first-order theory T is denoted αT and is a

function mapping every function symbol appearing in T to its arity. Addition-

ally, if no constant (i.e. symbols of arity 0) occurs in a formula of T we extend

αT on a symbol a not occurring in T with α(a) = 0.

This construction permits one to define the Herbrand’s domain HT of a

theory T as the set of terms T (α). In particular we note that this domain is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-50-320.jpg)

![4.5. FOUNDATIONS OF RESOLUTION 51

never empty, and is finite if, and only if, every function symbol occurring in T

is of arity 0.

Example 10. Assume:

T = ∀x∀ε∀x ¬(|x − x | < g(x, ε)) ∨ |f (x) − f (x )| < ε

Since T does not contain any constant its functional signature is the function

α:

α = {a → 0, | | → 1, f → 1, − → 2, g → 2}

The Herbrand’s domain HT is the set of terms:

a, |a|, f (a), a − a, g(a, a), ||a||, f (|a|), . . .

One easily sees that the Herbrand’s domain of a first-order theory is denumer-

able, the proof being left as an exercise to the reader.

Given a relational signature βT describing the arity of the predicate symbols

occurring in the clauses of T and the Herbrand’s domain HT we define the

Herbrand’s universe to be the set of atoms p(t1 , . . . , tn ) where β(p) = n and

t1 , . . . , tn ∈ HT . A term in HT or an atom in UT is said to be ground.

Definition 7. (Herbrand’s interpretation) A Herbrand’s interpretation of a

first-order theory T is an interpretation I in which the domain is the Herbrand’s

domain HT of T and such that, for every function symbol f occurring in T we

n

have I(f ) = (t1 , . . . , tn ) ∈ HT → f (t1 , . . . , tn ) ∈ HT .

Thus in a Herbrand’s interpretation the terms are both syntax and semantics

as they occur in the domain and in the formula. We note that since every

interpretation of T must interpret the function symbols occurring in T , the

Herbrand’s domain can be viewed as the set of all the expressions definable

in all interpretations of T . Accordingly given an interpretation I there exists

an embedding ΘI of the Herbrand’s universe into the set of distinct atoms in

I. Sinnce ΘI is a mapping the preimages of the atoms of the interpretation

are disjoints. Thus the truth value of an atom in the interpretation I can be

mapped to the truth value of the atoms in a Herbrand’s interpretation which are

in its preimage. For these reasons Herbrand’s universes are called the Canonical

models of first-order logic.

Given a clause C = ∀x1 . . . ∀xn l1 ∨ . . . ∨ lk of T a ground instance of C is a

clause l1 σ ∨ . . . ∨ lk σ where σ is a substitution mapping the variables x1 , . . . , xn

to ground terms t1 , . . . , tn of the Herbrand’s domain. We let T HT be the set of

all ground instances of all clauses in T .

Lemma 4.4. (Lemma 1.6.1 in [146]) A theory T is satisfiable if, and only if,

T HT is satisfied by a Herbrand’s interpretation.

Proof. ⇒ First let us prove that if T is satisfiable then T HT is satisfied by

a Herbrand’s interpretation. Let I be a model of T of domain D = ∅. If a](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/habilitation-110222100401-phpapp02/85/Habilitation-draft-51-320.jpg)

![52 CHAPTER 4. FUNDAMENTALS OF FIRST-ORDER LOGIC

constant a was added to the function symbols occurring in T , fix some c ∈ D

and set I(a) = c. Since I(f ) is defined for every function symbol occurring in

T , by structural induction on the terms, it is trivial that I can be extended

as a mapping from Θ : HT → D. We build a Herbrand’s model U of T HT as

follows:

for each predicate symbol p of arity n and for every ground terms

t1 , . . . , tn ∈ HT let

U(p(t1 , . . . , tn )) = I(p)(Θ(t1 ), . . . , Θ(tn ))

By contradiction assume that U is not a model of T HT . By definition there

exists a clause C = ∀x1 . . . ∀xn l1 ∨ . . . ∨ lk of T and a ground substitution σ

mapping the variables x1 , . . . , xn to ground terms t1 , . . . , tn of the Herbrand’s

domain such that:

U(l1 σ ∨ . . . ∨ lk σ) = ⊥

Reordering the literals if necessary let us fix the notations with atoms a1 , . . . , ak , bk +1 , . . . , bk

such that:

ai If i ≤ k

li σ =

¬bi If i > k

We have U(a1 ) = . . . = U(ak ) = ⊥ and U(bk +1 ) = . . . = U(bk ) = . By

construction every atom ai , bi has an image by Θ. By definition of U we have:

I(Θ(ai )) = ⊥

I(Θ(bi )) =

and thus I(l1 σ ∨ . . . ∨ lk σ) = ⊥. There is an instance of a clause of T which is

not evaluated to true by I, which contradicts the fact that I is an interpretation

of T . Thus U is a Herbrand’s model of T HT .

⇐ Trivial, since assume the existence of an interpretation in which all

instances of all clauses in T are satisfied.

Lemma 4.4 reduces the general problem of the (un)satisfiability of a first-

order theory to the particular case of the existence of a Herbrand’s model.

The cost to pay for this reduction is that we are now looking for a model of an

infinite set of ground clauses. We now follow Quine [183] to prove that it actually

suffices to consider finite sets of ground instances to derive the (un)satisfiability

of this infinite set of ground clauses. The proof relies depends on the notion of

condemnation.

Definition 8. (Condemnation) Let S be a finite set of ground clauses where