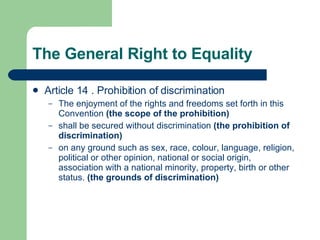

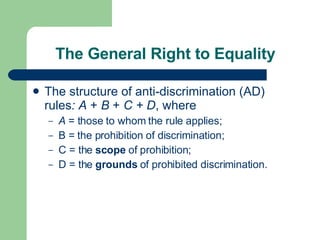

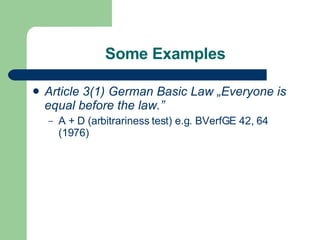

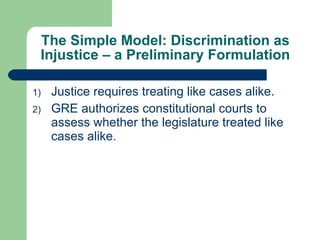

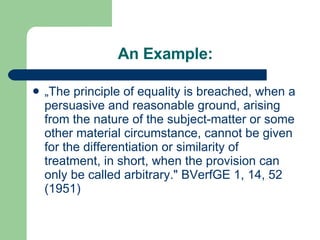

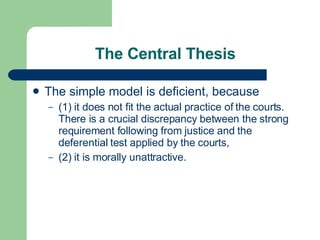

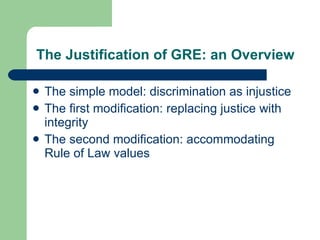

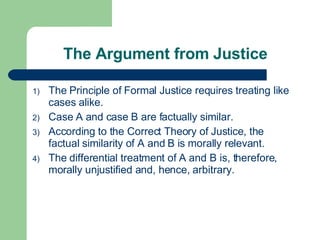

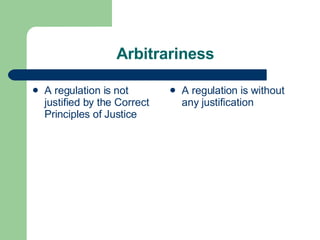

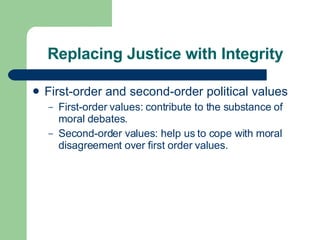

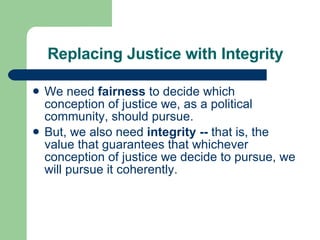

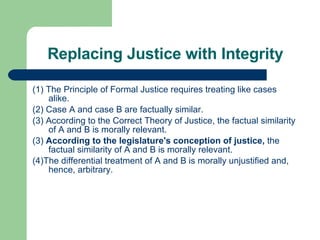

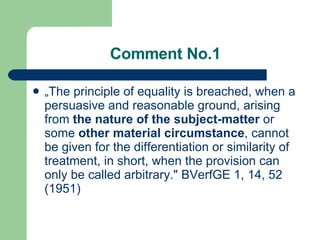

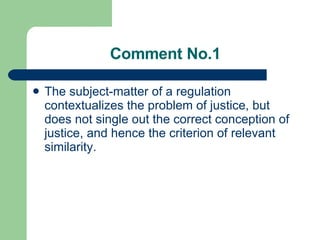

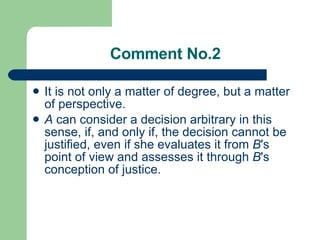

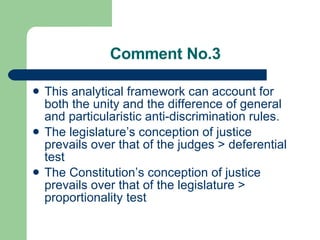

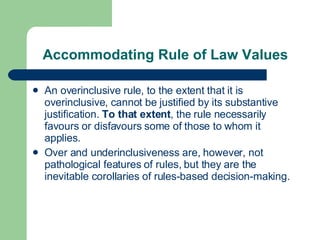

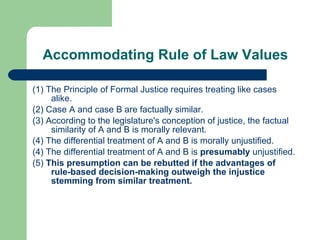

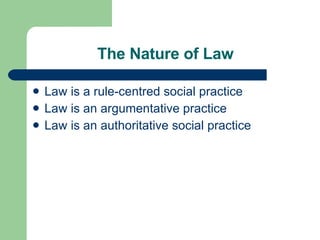

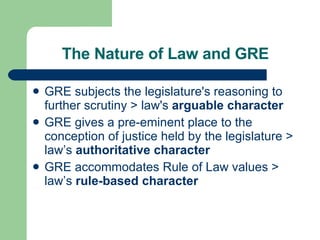

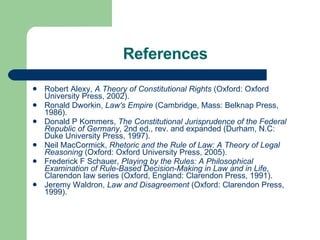

The document discusses the philosophical foundations of the general right to equality. It argues that the simple model of discrimination as injustice is deficient because it does not fit with how courts actually apply anti-discrimination rules in practice and is morally unattractive. The document proposes replacing the concept of justice with integrity and accommodating rule of law values to better justify the general right to equality in both theory and practice.