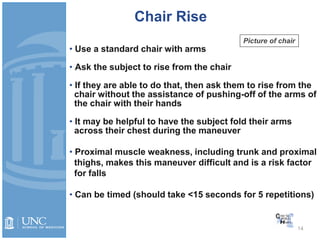

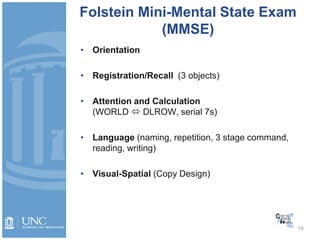

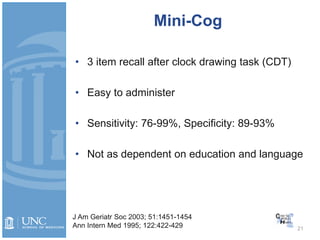

The document provides an overview of geriatric assessment techniques. It describes how to evaluate older adults' physical, cognitive, and psychosocial functioning. Key areas of assessment include activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, gait and falls risk, cognitive screening tools like the Mini-Mental State Exam and Mini-Cog, and depression screening scales. The document demonstrates these assessment techniques through examples and videos. It also provides cases to demonstrate how assessments inform care for older patients.