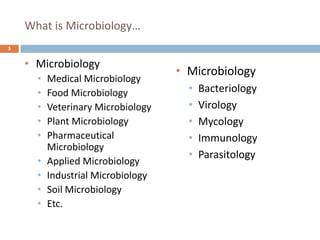

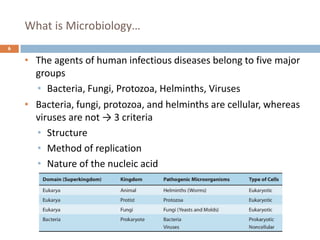

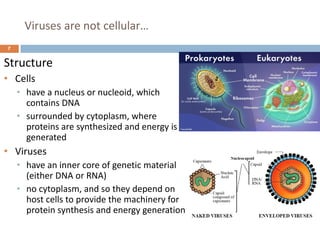

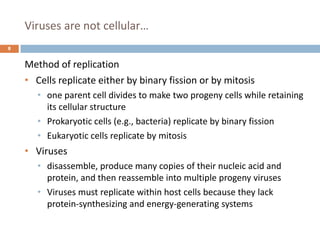

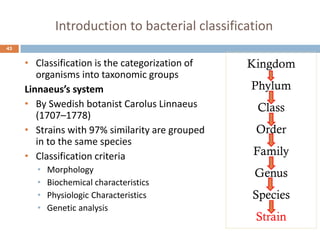

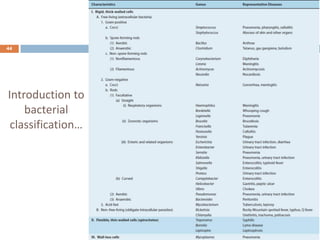

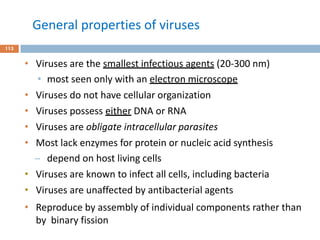

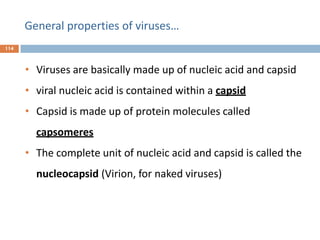

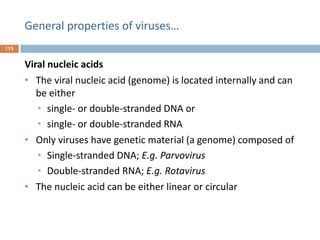

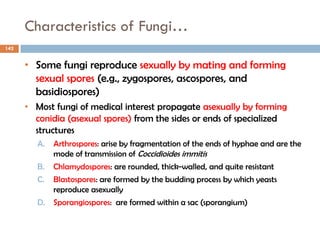

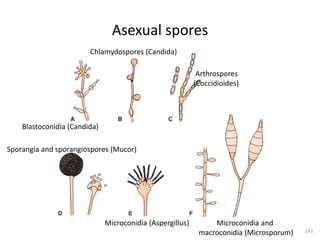

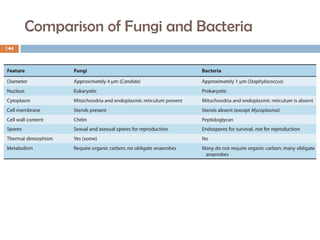

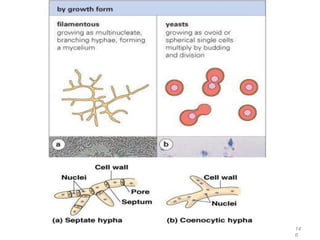

The document is a course outline for a microbiology program at Africa Medical College, focusing on various aspects of microbiology including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and their classifications. It covers topics such as general microbiology, systematic bacteriology, medical microbiology, and the germ theory of disease, along with assessment methods for students. Additionally, it outlines the structures and functions of microorganisms, providing foundational knowledge for medical microbiology students.

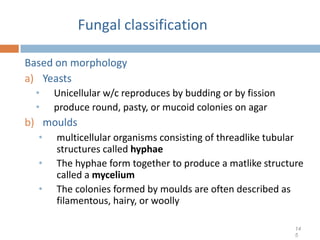

![Fungal classification…

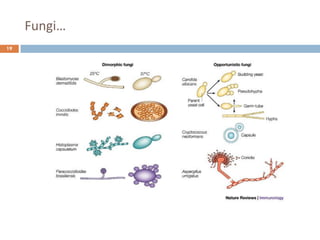

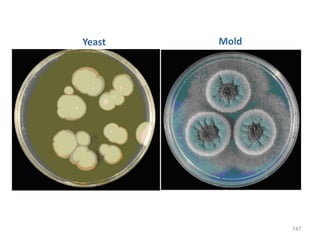

c. Dimorphic fungi

• exhibit thermal dimorphism (i.e., exist as yeast

at body temperature [37°C] and mould at room

temperature [25°C])

• Example

o Histoplasma capsulatum

o Blastomyces dermatitidis

o Coccidioides immitis

o Paracoccidioides brasiliensis

14

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/generalmicrobiology-amc-2024complete-250123143432-b2d9fe6c/85/General-Microbiology-AMC-2024_Complete-pdf-148-320.jpg)