This document provides a summary of a book on statistical signal processing and estimation theory. It discusses key topics covered in the book including minimum variance unbiased estimation, the Cramer-Rao lower bound, linear models, general minimum variance unbiased estimation, best linear unbiased estimation, maximum likelihood estimation, least squares estimation, the method of moments, Bayesian estimation approaches, linear Bayesian estimators such as Wiener filtering, Kalman filtering, and extensions for complex data and parameters. The book is intended as a textbook for graduate students in signal processing and provides both theoretical background and practical examples of parameter estimation techniques.

![xii PREFACE

and matrix algebra. This book can also be used for self-study and so should be useful

to the practicing engin.eer as well as the student.

The author would like to acknowledge the contributions of the many people who

over the years have provided stimulating discussions of research problems, opportuni-

ties to apply the results of that research, and support for conducting research. Thanks

are due to my colleagues L. Jackson, R. Kumaresan, L. Pakula, and D. Tufts of the

University of Rhode Island, and 1. Scharf of the University of Colorado. Exposure to

practical problems, leading to new research directions, has been provided by H. Wood-

sum of Sonetech, Bedford, New Hampshire, and by D. Mook, S. Lang, C. Myers, and

D. Morgan of Lockheed-Sanders, Nashua, New Hampshire. The opportunity to apply

estimation theory to sonar and the research support of J. Kelly of the Naval Under-

sea Warfare Center, Newport, Rhode Island, J. Salisbury of Analysis and Technology,

Middletown, Rhode Island (formerly of the Naval Undersea Warfare Center), and D.

Sheldon of th.e Naval Undersea Warfare Center, New London, Connecticut, are also

greatly appreciated. Thanks are due to J. Sjogren of the Air Force Office of Scientific

Research, whose continued support has allowed the author to investigate the field of

statistical estimation. A debt of gratitude is owed to all my current and former grad-

uate students. They have contributed to the final manuscript through many hours of

pedagogical and research discussions as well as by their specific comments and ques-

tions. In particular, P. Djuric of the State University of New York proofread much

of the manuscript, and V. Nagesha of the University of Rhode Island proofread the

manuscript and helped with the problem solutions.

Steven M. Kay

University of Rhode Island

Kingston, RI 02881

r

t

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 Estimation in Signal Processing

Modern estimation theory can be found at the heart of many electronic signal processing

systems designed to extract information. These systems include

1. Radar

2. Sonar

3. Speech

4. Image analysis

5. Biomedicine

6. Communications

7. Control

8. Seismology,

and all share the common problem of needing to estimate the values of a group of pa-

rameters. We briefly describe the first three of these systems. In radar we are mterested

in determining the position of an aircraft, as for example, in airport surveillance radar

[Skolnik 1980]. To determine the range R we transmit an electromagnetic pulse that is

reflected by the aircraft, causin an echo to be received b the antenna To seconds later~

as shown in igure 1.1a. The range is determined by the equation TO = 2R/c, where

c is the speed of electromagnetic propagation. Clearly, if the round trip delay To can

be measured, then so can the range. A typical transmit pulse and received waveform

a:e shown in Figure 1.1b. The received echo is decreased in amplitude due to propaga-

tIon losses and hence may be obscured by environmental nois~. Its onset may also be

perturbed by time delays introduced by the electronics of the receiver. Determination

of the round trip delay can therefore require more than just a means of detecting a

jump in the power level at the receiver. It is important to note that a typical modern

l](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-5-2048.jpg)

![2

Transmit/

receive

antenna

Transmit pulse

'-----+01 Radar processing

system

(a) Radar

....................... - - .................... -- ... -1

Received waveform

:---------_ ... -_... _-------,

TO ~--------- ... ------ .. -- __ ..!

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

Time

Time

(b) Transmit and received waveforms

Figure 1.1 Radar system

radar s!,stem will input the received continuous-time waveform into a digital computer

by takmg samples via an analog-to-digital convertor. Once the waveform has been

sampled, the data compose a time series. (See also Examples 3.13 and 7.15 for a more

detailed description of this problem and optimal estimation procedures.)

Another common application is in sonar, in which we are also interested in the

posi~ion of a target, such as a submarine [Knight et al. 1981, Burdic 1984] . A typical

passive sonar is shown in Figure 1.2a. The target radiates noise due to machiner:y

on board, propellor action, etc. This noise, which is actually the signal of interest,

propagates through the water and is received by an array of sensors. The sensor outputs

1.1. ESTIMATION IN SIGNAL PROCESSING 3

Sea surface

Towed array

Sea bottom

---------------~~---------------------------~

(a) Passive sonar

Sensor 1 output

~ Time

~'C7~ Time

Sensor 3 output

f ~ ~ / Time

(b) Received signals at array sensors

Figure 1.2 Passive sonar system

are then transmitted to a tow ship for input to a digital computer. Because of the

positions of the sensors relative to the arrival angle of the target signal, we receive

the signals shown in Figure 1.2b. By measuring TO, the delay between sensors, we can

determine the bearing f3 Z<!T t~e ~~ress.!.o~

(

eTO)

f3 = arccos d (1.1)

where c is the speed of sound in water and d is the distance between sensors (see

Examples 3.15 and 7.17 for a more detailed description). Again, however, the received](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-6-2048.jpg)

![4 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

-..... :~

<0

-.....

"&

0

.;, -1

-2

-3

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20

Time (ms)

o 8 10 14

Time (ms)

Figure 1.3 Examples of speech sounds

waveforms are not "clean" as shown in Figure 1.2b but are embedded in noise, making,

the determination of To more difficult. The value of (3 obtained from (1.1) is then onli(

an estimate.

- Another application is in speech processing systems [Rabiner and Schafer 1978].

A particularly important problem is speech recognition, which is the recognition of

speech by a machine (digital computer). The simplest example of this is in recognizing

individual speech sounds or phonemes. Phonemes are the vowels, consonants, etc., or

the fundamental sounds of speech. As an example, the vowels /al and /e/ are shown

in Figure 1.3. Note that they are eriodic waveforms whose eriod is called the pitch.

To recognize whether a sound is an la or an lei the following simple strategy might

be employed. Have the person whose speech is to be recognized say each vowel three

times and store the waveforms. To reco nize the s oken vowel com are it to the

stored vowe s and choose the one that is closest to the spoken vowel or the one that

1.1. ESTIMATION IN SIGNAL PROCESSING

S

:s

-.....

<0

-.....

<0

....

.,

u

"

C.

"'

u.

p.. -10

...:l

"'0 -20

<=

:d

-30~

S

E !

!?!' -40-+

-0 !

c -50 I

.;::

" 0

p..

S

::=.. 30

1

-.....

'" 2°i

-.....

<0

t 10-+

u

::;

C.

0

'"

U

"- -10

...:l

"2 -20

id I

~ -30

1

i

500 1000 1500

Frequency (Hz)

2000

I

2500

~ -40-+

~ -50il--------~I--------_r1--------TI--------T-------~----

0:: 0 500 1000 1500 2000 2500

Frequency (Hz)

Figure 1.4 LPC spectral modeling

5

minimizes some distance measure. Difficulties arise if the itch of the speaker's voice

c anges from the time he or s e recor s the sounds (the training session) to the time

when the speech recognizer is used. This is a natural variability due to the nature of

human speech. In practice, attributes, other than the waveforms themselves, are used

to measure distance. Attributes are chosen that are less sllsceptible to variation. For

example, the spectral envelope will not change with pitch since the Fourier transform

of a periodic signal is a sampled version of the Fourier transform of one period of the

signal. The period affects only the spacing between frequency samples, not the values.

To extract the s ectral envelo e we em 10 a model of s eech called linear predictive

coding LPC). The parameters of the model determine the s ectral envelope. For the

speec soun SIll 19ure 1.3 the power spectrum (magnitude-squared Fourier transform

divided by the number of time samples) or periodogram and the estimated LPC spectral

envelope are shown in Figure 1.4. (See Examples 3.16 and 7.18 for a description of how](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-7-2048.jpg)

![6 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

the parameters of the model are estimated and used to find the spectral envelope.) It

is interesting that in this example a human interpreter can easily discern the spoken

vowel. The real problem then is to design a machine that is able to do the same. In

the radar/sonar problem a human interpreter would be unable to determine the target

position from the received waveforms, so that the machine acts as an indispensable

tool.

In all these systems we are faced with the problem of extracting values of parameters

bas~ on continuous-time waveforms. Due to the use of di ital com uters to sample

and store e contmuous-time wave orm, we have the equivalent problem of extractin

parameter values from a discrete-time waveform or a data set. at ematically, we have

the N-point data set {x[O], x[I], ... ,x[N -In which depends on an unknown parameter

(). We wish to determine () based on the data or to define an estimator

{J = g(x[O],x[I], ... ,x[N - 1]) (1.2)

where 9 is some function. This is the problem of pammeter estimation, which is the

subject of this book. Although electrical engineers at one time designed systems based

on analog signals and analog circuits, the current and future trend is based on discrete-

time signals or sequences and digital circuitry. With this transition the estimation

problem has evolved into one of estimating a parameter based on a time series, which

is just a discrete-time process. Furthermore, because the amount of data is necessarily

finite, we are faced with the determination of 9 as in (1.2). Therefore, our problem has

now evolved into one which has a long and glorious history, dating back to Gauss who

in 1795 used least squares data analysis to predict planetary m(Wements [Gauss 1963

(English translation)]. All the theory and techniques of statisti~al estimation are at

our disposal [Cox and Hinkley 1974, Kendall and Stuart 1976-1979, Rao 1973, Zacks

1981].

Before concluding our discussion of application areas we complete the previous list.

4. Image analysis - Elstimate the position and orientation of an object from a camera

image, necessary when using a robot to pick up an object [Jain 1989]

5. Biomedicine - estimate the heart rate of a fetu~ [Widrow and Stearns 1985]

6. Communications - estimate the carrier frequency of a signal so that the signal can

be demodulated to baseband [Proakis 1983]

1. Control - estimate the position of a powerboat so that corrective navigational

action can be taken, as in a LORAN system [Dabbous 1988]

8. Seismology - estimate the underground distance of an oil deposit based on SOUD&

reflections dueto the different densities of oil and rock layers [Justice 1985].

Finally, the multitude of applications stemming from analysis of data from physical

experiments, economics, etc., should also be mentioned [Box and Jenkins 1970, Holm

and Hovem 1979, Schuster 1898, Taylor 1986].

1.2. THE MATHEMATICAL ESTIMATION PROBLEM 7

x[O]

Figure 1.5 Dependence of PDF on unknown parameter

1.2 The Mathematical Estimation Problem

In determining good .estimators the first step is to mathematically model the data.

~ecause the data are mherently random, we describe it by it§, probability density func-

tion (PDF) 01:" p(x[O], x[I], ... ,x[N - 1]; ()). The PDF is parameterized by the unknown

l2arameter ()J I.e., we have a class of PDFs where each one is different due to a different

value of (). We will use a semicolon to denote this dependence. As an example, if N = 1

and () denotes the mean, then the PDF of the data might be

p(x[O]; ()) = .:-." exp [__I_(x[O] _ ())2]

v 27rO'2 20'2

which is shown in Figure 1.5 for various values of (). It should be intuitively clear that

because the value of () affects the probability of xiO], we should be able to infer the value

of () from the observed value of x[OL For example, if the value of x[O] is negative, it is

doubtful tha~ () =:'.()2' :rhe value. (). = ()l might be more reasonable, This specification

of th~ PDF IS cntlcal m determmmg a good estima~. In an actual problem we are

not glv~n a PDF but .must choose one that is not only consistent with the problem

~onstramts and any pnor knowledge, but one that is also mathematically tractable. To

~llus~rate the appr~ach consider the hypothetical Dow-Jones industrial average shown

IP. FIgure 1.6. It. mIght be conjectured that this data, although appearing to fluctuate

WIldly, actually IS "on the average" increasing. To determine if this is true we could

assume that the data actually consist of a straight line embedded in random noise or

x[n] =A+Bn+w[n] n = 0, 1, ... ,N - 1.

~ reasonable model for the noise is that win] is white Gaussian noise (WGN) or each

sample of win] has the PDF N(0,O'2

) (denotes a Gaussian distribution with a mean

of 0 and a variance of 0'2) and is uncorrelated with all the other samples. Then, the

unknown parameters are A and B, which arranged as a vector become the vector

parameter 9 = [A Bf. Letting x = [x[O] x[I] ... x[N - lW, the PDF is

1 [1 N-l ]

p(x; 9) = (27rO'2)~ exp - 20'2 ~ (x[n]- A - Bn)2 . (1.3)

The choice of a straight line for the signal component is consistent with the knowledge

that the Dow-Jones average is hovering around 3000 (A models this) and the conjecture](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-8-2048.jpg)

![8 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

3200

3150

~

<'$

3100

...

" 3050

~

'Il

3000

"

~

0

.-, 2950

~

0

2900

0

2850

2800

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Day number

Figure 1.6 Hypothetical Dow-Jones average

that it is increasing (B > 0 models this). The assumption of WGN is justified by the

need to formulate a mathematically tractable model so that closed form estimators can

be found. Also, it is reasonable unless there is strong evidence to the contrary, such as

highly correlated noise. Of course, the performance of any estimator obtained will be

critically dependent on the PDF assum tions. We can onl hope the estimator obtained

is robust, in that slight changes in the PDF do not severely affect t per ormance of the

estimator. More conservative approaches utilize robust statistical procedures [Huber

1981J.

Estimation based on PDFs such as (1.3) is termed classical estimation in that the

parameters of interest are assumed to be deterministic but unknown. In the Dow-Jo~

average example we know a priori that the mean is somewhere around 3000. It seems

inconsistent with reality, then, to choose an estimator of A that can result in values as

low as 2000 or as high as 4000. We might be more willing to constrain the estimator

to produce values of A in the range [2800, 3200J. To incorporate this prior knowledge

we can assume that A is no Ion er deterministic but a random variable and assign it a

DF, possibly uni orm over the [2800, 3200J interval. Then, any subsequent estImator

will yield values in this range. Such an approach is termed Bayesian estimation. The

parameter we are attem tin to estimate is then viewed as a realization of the randQ;

, the data are described by the joint PDF

p(x,9) =p(xI9)p(9)

1.3. ASSESSING ESTIMATOR PERFORMANCE

3.0

i

2.5-+

1.0

"F.

fl 0.5

0.0

-1.0

-1.5

-{)'5~

-2.0-r--'I--il--il--il--il--II--II__"1'I__-+1----<1

o ill W ~ ~ M W m W 00 ~

n

Figure 1.7 Realization of DC level in noise

Once the PDF has been specified the problem becomes one f d t ..

" . ' 0 e ermmmg an

optImal estImator or functlOn of the data as in (1 2) Note that t' t

' . . an es Ima or may

depend on other par~meters, but only if they are known. An estimator may be thought

of as a rule that ~Sl ns a value to 9 for each realization of x. The estimate of 9 is

the va ue o. 9 obtal~ed .for a given realization of x. This distinction is analogous to a

random vanable (whIch IS a f~nction defined on the sample space) and the value it takes

on. Althoug~ some authors dIstinguish between the two by using capital and lowercase

letters, we WIll not do so. The meaning will, hopefully, be clear from the context.

1.3 Assessing Estimator Performance

Consider.the data set shown in Figure 1.7. From a cursory inspection it appears that

x[n] conslst~ of.a DC.level A in noise. (The use of the term DC is in reference to direct

current, whIch IS eqUlvalent to the constant function.) We could model the data as

x[nJ =A +wIn]

;~re w n denotes so~e zero ~ean noise ro~~ss. B~ed on the data set {x[O], x[1], .. .,

(

[[ .l]), we would .hke to estImate A. IntUltlvely, smce A is the average level of x[nJ

w nJ IS zero mean), It would be reasonable to estimate A as

I N-l

.4= N Lx[nJ

n=O

or by the sample mean of the data. Several questions come to mind:

I 1. How close will .4 be to A?

' 2. Are there better estimators than the sample mean?

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-9-2048.jpg)

![10 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

For the data set in Figure 1.7 it turns out that .1= 0.9, which is close to the true value

of A = 1. Another estimator might be

A=x[o].

Intuitively, we would not expect this estimator to perform as well since it does not

make use of all the data. There is no averaging to reduce the noise effects. However,

for the data set in Figure 1.7, A = 0.95, which is closer to the true value of A than

the sample mean estimate. Can we conclude that A is a better estimator than A?

The answer is of course no. Because an estimator is a function of the data, which

are random variables, it too is a random variable, subject to many possible outcomes.

The fact that A is closer to the true value only means that for the given realization of

data, as shown in Figure 1.7, the estimate A = 0.95 (or realization of A) is closer to

the true value than the estimate .1= 0.9 (or realization of A). To assess performance

we must do so statistically. One possibility would be to repeat the experiment that

generated the data and apply each estimator to every data set. Then, we could ask

which estimator produces a better estimate in the majority of the cases. Suppose we

repeat the experiment by fixing A =1 and adding different noise realizations of win] to

generate an ensemble of realizations of x[n]. Then, we determine the values of the two

estimators for each data set and finally plot the histograms. (A histogram describes the

number of times the estimator produces a given range of values and is an approximation

to the PDF.) For 100 realizations the histograms are shown in Figure 1.8. It should

now be evident that A is a better estimator than A because the values obtained are

more concentrated about the true value of A =1. Hence, Awill uliWl-lly produce a value

closer to the true one than A. The skeptic, however, might argue-that if we repeat the

experiment 1000 times instead, then the histogram of A will be more concentrated. To

dispel this notion, we cannot repeat the experiment 1000 times, for surely the skeptic

would then reassert his or her conjecture for 10,000 experiments. To prove that A is

better we could establish that the variance is less. The modeling assumptions that we

must employ are that the w[n]'s, in addition to being zero mean, are uncorrelated and

have equal variance u 2

. Then, we first show that the mean of each estimator is the true

value or

(

1 N-l )

E(A) E N ~ x[nJ

1 N-l

= N L E(x[n])

n=O

A

E(A) E(x[O])

A

so that on the average the estimators produce the true value. Second, the variances are

(

1 N-l )

var(A) = var N ~ x[nJ

1.3. ASSESSING ESTIMATOR PERFORMANCE

30

r

'" 25j

'0 15

lil

1

20

j

r:~i------rl- r - I------;--------1~JI~m---r---I_

-3 -2 -1 0 2 ~

-1

Sample mean value, A

o

'I

1

i

I

First sample value, A

2 3

Figure 1.8 Histograms for sample mean and first sample estimator

1 N-l

N2 L var(x[nJ)

n=O

1 2

N2

Nu

u2

N

since the w[nJ's are uncorrelated and thus

var(A) var(x[OJ)

u2

> var(A).

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-10-2048.jpg)

![12 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

Furthermore, if we could assume that w[n] is Gaussian, we could also conclude that the

probability of a given magnitude error is less for A. than for A (see Problem 2.7).

ISeveral important points are illustrated by the previous example, which should

always be ept in mind.

1. An estimator is a random variable. As such, its erformance can onl be com-

pletely descri e statistical y or by its PDF.

2. The use of computer simulations for assessing estimation performance, although

quite valuable for gaiiiing insight and motivating conjectures, is never conclusive.

At best, the true performance may be obtained to the desired degree of accuracy.

At worst, for an insufficient number of experiments and/or errors in the simulation

techniques employed, erroneous results may be obtained (see Appendix 7A for a

further discussion of Monte Carlo computer techniques).

Another theme that we will repeatedly encounter is the tradeoff between perfor:

mance and computational complexity. As in the previous example, even though A

has better performance, it also requires more computation. We will see that QPtimal

estimators can sometimes be difficult to implement, requiring a multidimensional opti-

mization or inte ration. In these situations, alternative estimators that are suboptimal,

but which can be implemented on a igita computer, may be preferred. For any par-

ticular application, the user must determine whether the loss in performance is offset

by the reduced computational complexity of a suboptimal estimator.

1.4 Some Notes to the Reader

Our philosophy in presenting a theory of estimation is to provide the user with the

main ideas necessary for determining optimal estimator.§. We have included results

that we deem to be most useful in practice, omitting some important theoretical issues.

The latter can be found in many books on statistical estimation theory which have

been written from a more theoretical viewpoint [Cox and Hinkley 1974, Kendall and

Stuart 1976--1979, Rao 1973, Zacks 1981]. As mentioned previously, our goal is t<;)

obtain an 0 timal estimator, and we resort to a subo timal one if the former cannot

be found or is not implementa ~. The sequence of chapters in this book follows this

approach, so that optimal estimators are discussed first, followed by approximately

optimal estimators, and finally suboptimal estimators. In Chapter 14 a "road map" for

finding a good estimator is presented along with a summary of the various estimators

and their properties. The reader may wish to read this chapter first to obtain an

overview.

We have tried to maximize insight by including many examples and minimizing

long mathematical expositions, although much of the tedious algebra and proofs have

been included as appendices. The DC level in noise described earlier will serve as a

standard example in introducing almost all the estimation approaches. It is hoped

that in doing so the reader will be able to develop his or her own intuition by building

upon previously assimilated concepts. Also, where possible, the scalar estimator is

REFERENCES 13

presented first followed by the vector estimator. This approach reduces the tendency

of vector/matrix algebra to obscure the main ideas. Finally, classical estimation is

described first, followed by Bayesian estimation, again in the interest of not obscuring

the main issues. The estimators obtained using the two approaches, although similar

in appearance, are fundamentally different.

The mathematical notation for all common symbols is summarized in Appendix 2.

The distinction between a continuous-time waveform and a discrete-time waveform or

sequence is made through the symbolism x(t) for continuous-time and x[n] for discrete-

time. Plots of x[n], however, appear continuous in time, the points having been con-

nected by straight lines for easier viewing. All vectors and matrices are boldface with

all vectors being column vectors. All other symbolism is defined within the context of

the discussion.

References

Box, G.E.P., G.M. Jenkins, Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Contro~ Holden-Day, San

Francisco, 1970.

Burdic, W.S., Underwater Acoustic System Analysis, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1984.

Cox, D.R., D.V. Hinkley, Theoretical Statistics, Chapman and Hall, New York, 1974.

Dabbous, T.E., N.U. Ahmed. J.C. McMillan, D.F. Liang, "Filtering of Discontinuous Processes

Arising in Marine Integrated Navigation," IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst., Vol. 24,

pp. 85-100, 1988.

Gauss, K.G., Theory of Motion of Heavenly Bodies, Dover, New York, 1963.

Holm, S., J.M. Hovem, "Estimation of Scalar Ocean Wave Spectra by the Maximum Entropy

Method," IEEE J. Ocean Eng., Vol. 4, pp. 76-83, 1979.

Huber, P.J., Robust Statistics, J. Wiley, ~ew York, 1981.

Jain, A.K., Fundamentals of Digital Image ProceSSing, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1989.

Justice, J.H.. "Array Processing in Exploration Seismology," in Array Signal Processing, S. Haykin,

ed., Prentice-HaU, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1985.

Kendall, Sir M., A. Stuart, The Advanced Theory of Statistics, Vols. 1-3, Macmillan, New York,

1976--1979.

Knight, W.S., RG. Pridham, S.M. Kay, "Digital Signal Processing for Sonar," Proc. IEEE, Vol.

69, pp. 1451-1506. Nov. 1981.

Proakis, J.G., Digital Communications, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1983.

Rabiner, L.R., RW. Schafer, Digital Processing of Speech Signals, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs,

N.J., 1978.

Rao, C.R, Linear Statistical Inference and Its Applications, J. Wiley, New York, 1973.

Schuster, !," "On the Investigation of Hidden Periodicities with Application to a Supposed 26 Day

.PerIod of Meterological Phenomena," Terrestrial Magnetism, Vol. 3, pp. 13-41, March 1898.

Skolmk, M.L, Introduction to Radar Systems, McGraw-Hill, ~ew York, 1980.

Taylor, S., Modeling Financial Time Series, J. Wiley, New York, 1986.

Widrow, B., Stearns, S.D., Adaptive Signal Processing, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1985.

Zacks, S., Parametric Statistical Inference, Pergamon, New York, 1981.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-11-2048.jpg)

![14

Problems

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

1. In a radar system an estimator of round trip delay To has the PDF To ~ N(To, (J~a)"

where 7< is the true value. If the range is to be estimated, propose an estimator R

and find its PDF. Next determine the standard deviation (J-ra so that 99% of th~

time the range estimate will be within 100 m of the true value. Use c = 3 x 10

mls for the speed of electromagnetic propagation.

2. An unknown parameter fJ influences the outcome of an experiment which is mod-

eled by the random variable x. The PDF of x is

p(x; fJ) = vkexp [-~(X -fJ?) .

A series of experiments is performed, and x is found to always be in the interval

[97, 103]. As a result, the investigator concludes that fJ must have been 100. Is

this assertion correct?

3. Let x = fJ +w, where w is a random variable with PDF Pw(w)..IfbfJ is (a dfJet)er~in~

istic parameter, find the PDF of x in terms of pw and denote It y P x; ... ex

assume that fJ is a random variable independent of wand find the condltlO?al

PDF p(xlfJ). Finally, do not assume that eand ware independent and determme

p(xlfJ). What can you say about p(x; fJ) versus p(xlfJ)?

4. It is desired to estimate the value of a DC level A in WGN or

x[n] = A +w[n] n = 0,1, ... , N - C

where w[n] is zero mean and uncorrelated, and each sample has variance (J2 = l.

Consider the two estimators

1 N-I

N 2:: x[n]

n=O

A =

A _1_ (2X[0] +~ x[n] +2x[N - 1]) .

N + 2 n=1

Which one is better? Does it depend on the value of A?

5. For the same data set as in Problem 1.4 the following estimator is proposed:

{

x [0]

A= ~'~x[n] A2 = A2 < 1000.

.,.2 -

The rationale for this estimator is that for a high enough signal-to-noise ratio

(SNR) or A2/(J2, we do not need to reduce the effect of.noise by averaging and

hence can avoid the added computation. Comment on thiS approach.

Chapter 2

Minimum Variance Unbiased

Estimation

2.1 Introduction

In this chapter we will be in our search for good estimators of unknown deterministic

parame ers. e will restrict our attention to estimators which on the average yield

the true parameter value. Then, within this class of estimators the goal will be to find

the one that exhibits the least variability. Hopefully, the estimator thus obtained will

produce values close to the true value most of the time. The notion of a minimum

variance unbiased estimator is examined within this chapter, but the means to find it

will require some more theory. Succeeding chapters will provide that theory as well as

apply it to many of the typical problems encountered in signal processing.

2.2 Summary

An unbiased estimator is defined by (2.1), with the important proviso that this holds for

all possible values of the unknown parameter. Within this class of estimators the one

with the minimum variance is sought. The unbiased constraint is shown by example

to be desirable from a practical viewpoint since the more natural error criterion, the

minimum mean square error, defined in (2.5), generally leads to unrealizable estimators.

Minimum variance unbiased estimators do not, in eneral, exist. When they do, several

methods can be used to find them. The methods reI on the Cramer-Rao ower oun

and the concept of a sufficient statistic. If a minimum variance unbiase estimator

does not exist or if both of the previous two approaches fail, a further constraint on the

estimator, to being linear in the data, leads to an easily implemented, but suboptimal,

estimato!,;

15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-12-2048.jpg)

![16 CHAPTER 2. MINIMUM VARIANCE UNBIASED ESTIMATION

2.3 Unbiased Estimators

For an estimator to be unbiased we mean that on the average the estimator will yield

the true value of the unknown parameter. Since the parameter value may in general be

anywhere in the interval a < 8 < b, unbiasedness asserts that no matter what the true

value of 8, our estimator will yield it on the average. Mathematically, an estimator i~

~~~il •

E(iJ) = 8 (2.1)

where (a,b) denotes the range of possible values of 8.

Example 2.1 - Unbiased Estimator for DC Level in White Gaussian Noise

Consider the observatioJ!s

x[n) = A +w[n) n = 0, 1, ... ,N - 1

where A is the parameter to be estimated and w[n] is WGN. The parameter A can

take on any value in the interval -00 < A < 00. Then, a reasonable estimator for the

average value of x[n] is

or the sample mean. Due to the linearity properties of the expectation operator

[

1 N-1 ]

E(A.) = E N ~ x[n)

1 N-1

N L E(x[nJ)

n=O

N-1

~LA

n=O

= A

for all A. The sample mean estimator is therefore unbiased.

(2.2)

<>

In this example A can take on any value, although in general the values of an unknown

parameter may be restricted by physical considerations. Estimating the resistance R

of an unknown resistor, for example, would necessitate an interval 0 < R < 00.

Unbiased estimators tend to have symmetric PDFs centered about the true value of

8, although this is not necessary (see Problem 2.5). For Example 2.1 the PDF is shown

in Figure 2.1 and is easily shown to be N(A, (72/N) (see Problem 2.3).

The restriction that E(iJ) =8 for all 8 is an important one. Lettin iJ =

x = [x 0 x , it asserts that

E(iJ) = Jg(x)p(x; 8) dx = 8 for all 8. (2.3)

2.3. UNBIASED ESTIMATORS 17

A

Figure 2.1 Probability density function for sample mean estimator

It is possible, however, that (2.3) may hold for some values of 8 and not others as the

next example illustrates. '

Example 2.2 - Biased Estimator for DC Level in White Noise

Consider again Example 2.1 but with the modified sample mean estimator

Then,

_ 1 N-1

A= 2N Lx[n].

E(A)

n=O

~A

2

A if A=O

# A if A # o.

It is seen that (2.3) holds for the modified estimator only for A = o. Clearly, A is a

biased estimator. <>

That an estimator is unbiased does not necessarily mean that it is a good estimator.

It only guarantees that on the average it will attain the true value. On the other hand

biased estimators are ones that are characterized by a systematic error, which presum~

ably should not be present. A persistent bias will always result in a poor estimator.

As an example, the unbiased property has an important implication when several es-

timators are combined (see Problem 2.4). ~t s?metimes occurs that multiple estimates

~th~ same paran:eter ar.e available, i.e., {81, 82 , •.. , 8n }. A reasonable procedure is to

combme these estimates mto, hopefully, a better one by averaging them to form

. 1 ~.

8=- ~8i.

n i=l

(2.4)

Assuming the estimators are unbiased, with the same variance, and uncorrelated with

each other,

E(iJ) = 8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-13-2048.jpg)

![X[~] ~ N (f)/ 1 )

X [1] -'?- f'I C~, 1) , &;; 0 I

') N (f), 2) ) 9-.( 0 (

i1" ~ [X[,1+ x[l] )

'2

O

2 > !.. ('2. Xfr,J + X[11)

q,

ry 1"

tt;:; [~1 ~2 ~ -- &p 1

~= [9~~~.~Sp]" I

-----.• _-_........_. ..

f. (~);: @'1' Qi 1. ~. <(. J L i £. p -=>

' 1 '9t I - t

GJ-~')~D-.-----:-===:====---:::::--~-...------:;-----====--

'- tlt¥;0: 0'"" J:, ~ e, l : r I (!. ~~,_

f J.!.*

~il ;! ,1

-I '" '>1 ( 1 'v H 1

'" ,". [J

!:'

tJ )"7. "'A J IJ ~~ Ju Z.

~ k<(-' :r&; - ~ ?: t .1

1; ~ 9. .f C J~ L~( I

N ,=, tV '>1 1~' )/'J 1:" 1

~@( ' ")2 .. Q. ~ ~ '" ~ ("'--1 .J -1 1 J 1~ ~ ~I-

" 1: -=., i ~i - -::; E Z&i . t :c9i i- -; to ?:Sr: .

~ '<I N '''-' ,tl IJ ,.,

~ .(}oJ A)1 ~ (t ) IV A ~Z r ~ 1fI A ~ ). JJ ;

;, -;- t "[: @,: - - E. L 1)1 = - t (L" e

i

_ E [~

IV ,. I /VZ ,-., N' ;., I ,<I

~ ~~9~~: _t f-(e~-E~e~n ;t(l;~e/~_E1S

i ~2)

q ~ I ,., .... I .. -.~~ 1 .=: I

/ ~ ')

i; ~~6/(..(li~/~ E

~t~~i~ f~~J'1?~it~914

tl"~tt~&.~ i~-ks--J> 1~0; ~~C ~&j ~"t, { G1 ~_](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-14-2048.jpg)

![20 CHAPTER 2. MINIMUM VARIANCE UNBIASED ESTIMATION

var(8)

_ iii

-+-----

-4-------- 8

2

-1_____--- 83 = MVU estimator

--~------------------- 9

(a)

var(8)

_+-__----- 81

- - 82

03

NoMVU

estimator

--+-----~~----------- 9

90

(b)

Figure 2.3 Possible dependence of estimator variance with (J

From a practical view oint the minimum MSE estimator needs to be abandoned.

An alternative approach is to constrain t e bias to be zero and find the estimator which

minimizes the variance. Such an estimator is termed the minimum variance unbiased

(MVU) estimator. Note that from (2.6) that the MSE of an unbiased estimator is just

the variance.

Minimizing the variance of an unbiased estimator also has the effect of concentrating

the PDF of the estimation error, 0- B, about zero (see Problem 2.7). The estimatiw

error Will therefore be less likely to be large.

2.5 Existence of the Minimum Variance Unbiased

Estimator

The uestion arises as to whether a MVU estimator exists Le., an unbiased estimator

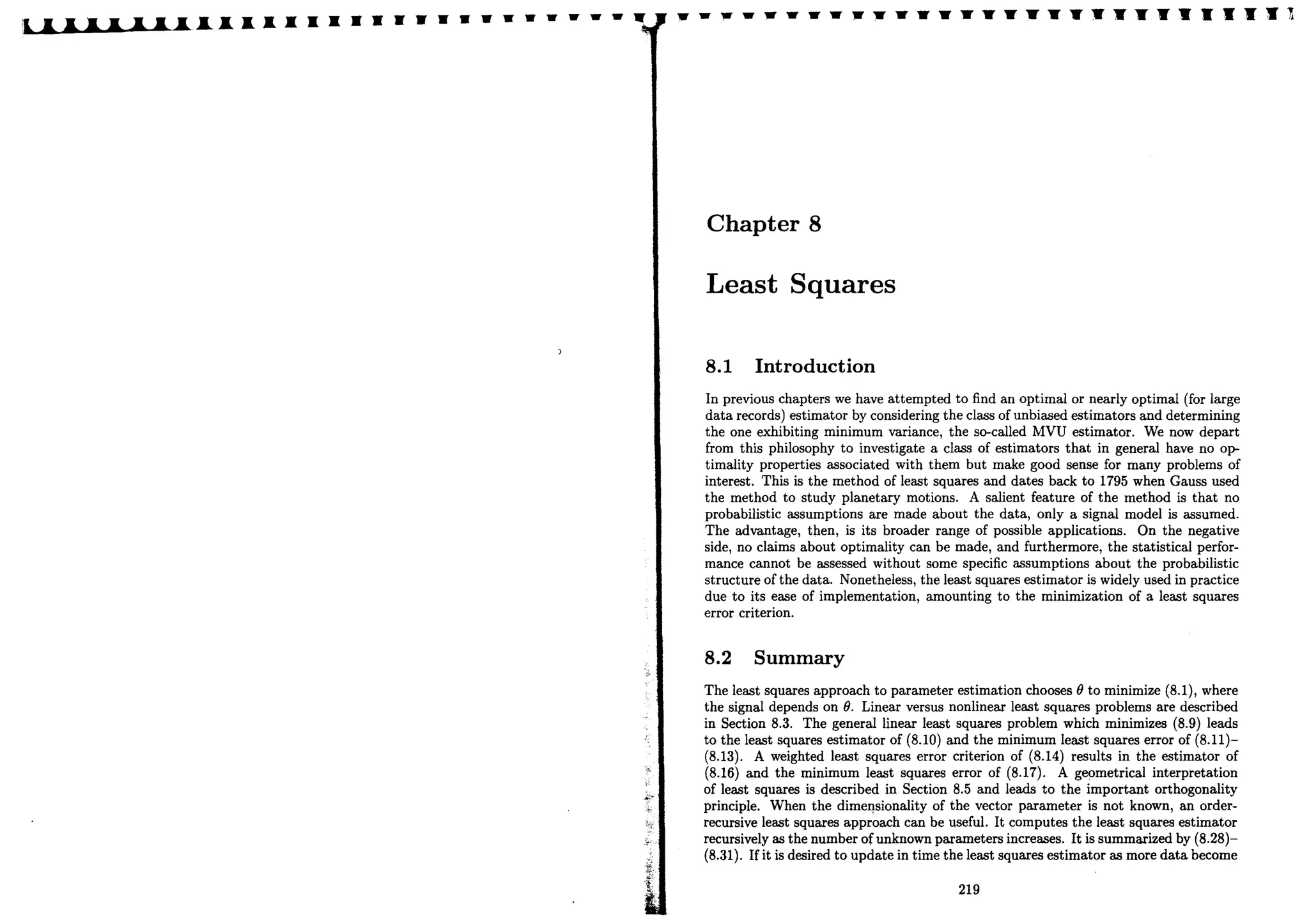

wit minimum variance for all B. Two possible situations are describe in Figure ..

If there are three unbiased estimators that exist and whose variances are shown in

Figure 2.3a, then clearly 03 is the MVU estimator. If the situation in Figure 2.3b

exists, however, then there is no MVU estimator since for B < Bo, O

2 is better, while

for iJ > Bo, 03 is better. In the former case 03 is sometimes referred to as the uniformly

minimum variance unbiased estimator to emphasize that the variance is smallest for

all B. In general, the MVU estimator does not always exist, as the following example

illustrates. .

Example 2.3 - Counterexample to Existence of MVU Estimator

Ifthe form ofthe PDF changes with B, then it would be expected that the best estimator

would also change with B. Assume that we have two independent observations x[Q] and

x[l] with PDF

x [0]

x[l]

N(B,l)

{

N(B,l)

N(B,2)

if B~ Q

if B< O.

••7F."'F'~· __ ·_ _

' ' ' ' '. . . . ._ _ _ _- _ _

:"'$

FINDING THE MVU ESTIMATOR

2.6.

var(ii)

_------"127

/

36

•••••••••.••.•.••••·2·ciiji :~!~?.................. ii2

21

18/36 01

__---------t--------------- 9

Figure 2.4 Illustration of nonex-

istence of minimum variance unbi-

ased estimator

The two estimators

1

- (x[Q] + x[l])

2

2 1

-x[Q] + -x[l]

3 3

can easily be shown to be unbiased. To compute the variances we have that

so that

and

1

- (var(x[O]) +var(x[l]))

4

4 1

-var(x[O]) + -var(x[l])

9 9

¥s if B< O.

The variances are shown in Figure 2.4. Clearly, between these two esti~~tors no M:'U

estimator exists. It is shown in Problem 3.6 that for B ~ 0 the mInimum possible

variance of an unbiased estimator is 18/36, while that for B < 0 is 24/36. Hence, no

single estimator can have a variance uniformly less than or equal to the minima shown

in Figure 2.4. 0

To conclude our discussion of existence we should note that it is also possible that there

may not exist even a single unbiased estima.!2E (see Problem 2.11). In this case any

search for a MVU estimator is fruitless.

2.6 Finding the Minimum Variance

Unbiased Estimator

Even if a MVU estimator exists, we may not be able to find it.

urn-t e-crank" procedure which will always produce the estimator.

chapters we shall discuss several possible approaches. They are:

is no known

In the next few](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-16-2048.jpg)

![22 CHAPTER 2. MINIMUM VARIANCE UNBIASED ESTIMATION

var(O)

............ •••••••••••••••····CRLB Figure 2.5 Cramer-Rao

----------------r-------------------- 9 lower bound on variance of unbiased

estimator

1. Determine the Cramer-Rao lower bound CRLB and check to see if some estimator

satisfies it Chapters 3 and 4).

2. Apply the Rao-Blackwell-Lehmann-Scheffe (RBLS) theorem (Chapter 5).

3. Further restrict the class of estimators to be not only unbiased but also linear. Then,

find the minimum variance estimator within this restricted class (Chapte~ 6).

Approaches 1 and 2 may produce the MVU estimator, while 3 will yield it only if the

MVU estimator is linear III the data.

The CRLB allows us to determine that for any unbiased estimator the variance

must be greater than or equal to a given value, as shown in Figure 2.5. If an estimator

exists whose variance equals the CRLB for each value of (), then it must be the MVU

estimator. In this case, the theory of the CRLB immediately yields the estimator. It

may happen that no estimator exists whose variance equals the bound. Yet, a MV~

estimator may still exist, as for instance in the case of ()! in Figure 2.5. Then, we

must resort to the Rao-Blackwell-Lehmann-Scheffe theorem. Thts procedure first find;

a su czen s atistic, one whic uses a the data efficient! and then nds a unction

of the su dent statistic which is an unbiased estimator oL(}. With a slight restriction

of the PDF of the data this procedure will then be guaranteed to produce the MVU

estimator. The third approach requires the estimator to be linear, a sometimes severe

restriction, and chooses the best linear estimator. Of course, only for particular data

sets can this approach produce the MVU estimator.

.

2.7 Extension to a Vector Parameter

If 8 = [(}l (}2 •.. (}"jT is a vector of unknown parameter~, then we say that an estimator

, A A 'T •

8 = [(}1 (}2 •.• (},,] is unbiase~j,f

ai < (}i < b; (2.7)

for i = 1,2, ... ,p. By defining

REFERENCES 23

we can equivalently define an unbiased estimator to have the property

E(8) = 8

for every 8 contained wjthjn the space defined in (2.7). A MVU estimator has the

~ditional property that var(Bi) for i = 1,2, ... ,p is minimum among all unbiased

estimators.

References

Bibbv, J .. H. Toutenburg, Prediction and Improved Estimation in Linear Models, J. Wiley, New

. York, 1977.

Rao, C.R., Linear Statistical Inference and Its Applications, J. Wiley, New York, 1973.

Stoica, P., R. Moses, "On Biased Estimators and the Unbiased Cramer-Rao Lower Bound," Signal

Process., Vol. 21, pp. 349-350, 1990.

Problems

2.1 The data {x[O], x[I], ... ,x[N - I]} are observed where the x[n]'s are independent

and identically distributed (lID) as N(0,a2

). We wish to estimate the variance

a2

as

Is this an unbiased estimator? Find the variance of ;2 and examine what happens

as N -t 00.

2.2 Consider the data {x[O],x[I], ... ,x[N -l]}, where each sample is distributed as

U[O, ()] and the samples are lID. Can you find an unbiased estimator for ()? The

range of () is 0 < () < 00.

2.3 Prove that the PDF of Agiven in Example 2.1 is N(A, a2

IN).

2.4 The heart rate h of a patient is automatically recorded by a computer every 100 ms.

In 1 s the measurements {hI, h2 , ••• , hlO } are averaged to obtain h. If E(h;) = ah

for some constant a and var(hi) = 1 for each i, determine whether averaging

improves the estimator if a = 1 and a = 1/2. Assume each measurement is

uncorrelated.

2.5 Two samples {x[0], x[l]} are independently observed from a N(O, a2 ) distribution.

The estimator

A 1

a2

= 2'(x2

[0] + x2

[1])

is unbiased. Find the PDF of ;2 to determine if it is symmetric about a2 •](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-17-2048.jpg)

![24

CHAPTER 2. MINIMUM VARIANCE UNBIASED ESTIMATION

2.6 For the problem described in Example 2.1 the more general estimator

.v-I

A = L anx[n]

n=O

is proposed. Find the an's so that the estimator is unbiased and the variance is

minimized. Hint: Use Lagrangian mUltipliers with unbiasedness as the constraint

equation.

2.7 Two unbiased estimators are proposed whose variances satisfy var(O) < var(B). If

both estimators are Gaussian, prove that

for any f: > O. This says that the estimator with less variance is to be preferred

since its PDF is more concentrated about the true value.

2.8 For the problem described in Example 2.1 show that as N -t 00, A-t A by using

the results of Problem 2.3. To do so prove that

lim Pr {IA - AI> f:} = 0

N-+oo

for any f: > O. In this case the estimator A is said to be consistent. Investigate

what happens if the alternative estimator A = 2~ L::OI x[n] is used instead.

2.9 This problem illustrates what happens to an unbiased est!1nator when it undergoes

a nonlinear transformation. In Example 2.1, if we choose to estimate the unknown

parameter () = A2 by

0= (~ ~Ix[n]r,

can we say that the estimator is unbiased? What happens as N -t oo?

2.10 In Example 2.1 assume now that in addition to A, the value of 172 is also unknown.

We wish to estimate the vector parameter

Is the estimator

, N Lx[n]

A n=O

[

1 N-I ]

[,;,1~ N ~1 ~(x[n] - A)'

unbiased?

PROBLEMS 25

. I bservation x[O] from the distribution Ufo, 1/(}], it is desired to

2.11 Given a sm

g

r e. 0 d that () > O. Show that for an estimator 0= g(x[O]) to

estimate (). t IS assume

be unbiased we must have

1#g(u)du = l.

. that a function 9 cannot be found to satisfy this condition for all () > O.

Next prove](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-18-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 3

Cramer-Rao Lower Bound

3.1 Introduction

Being able to place a lower bound on the variance of any unbiased estimator proves

to be extremely useful in practice. At best, it allows us to assert that an estimator is

the MVU estimator. This will be the case if the estimator attains the bound for all

values of the unknown parameter. At worst, it provides a benchmark against which we

can compare the performance of any unbiased estimator. Furthermore, it alerts us to

the physical impossibility of finding an unbiased estimator whose variance is less than

the bound. The latter is often useful in signal processing feasibility studies. Although

many such variance bounds exist [McAulay and Hofstetter 1971, Kendall and Stuart

1979, Seidman 1970, Ziv and Zakai 1969], the Cramer-Rao lower bound (CRLB) is by

far the easiest to determine. Also, the theory allows us to immediately determine if

an estimator exists that attains the bound. If no such estimator exists, then all is not

lost since estimators can be found that attain the bound in an approximate sense, as

described in Chapter 7. For these reasons we restrict our discussion to the CRLB.

3.2 Summary

The CRLB for a scalar parameter is given by (3.6). If the condition (3.7) is satisfied,

then the bound will be attained and the estimator that attains it is readily found.

An alternative means of determining the CRLB is given by (3.12). For a signal with

an unknown parameter in WGN, (3.14) provides a convenient means to evaluate the

bound. When a function of a parameter is to be estimated, the CRLB is given by

(3.16). Even though an efficient estimator may exist for (), in general there will not be

one for a function of () (unless the function is linear). For a vector parameter the CRLB

is determined using (3.20) and (3.21). As in the scalar parameter case, if condition

(3.25) holds, then the bound is attained and the estimator that attains the bound is

easily found. For a function of a vector parameter (3.30) provides the bound. A general

formula for the Fisher information matrix (used to determine the vector CRLB) for a

multivariate Gaussian PDF is given by (3.31). Finally, if the data set comes from a

27](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-19-2048.jpg)

![28

CHAPTER 3. CRAMER-RAO LOWER BOUND

PI (x[0] =3; A)

p2(X[0] = 3; A)

__r--r__~-r--~-r--r-------- A

2 3 4 5 6

2 3 4 5 6

(a) <11 = 1/3 (b) <12 = 1

Figure 3.1 PDF dependence on unknown parameter

WSS Gaussian random process, then an approximate CRLB, that depends on the PSD,

is given by (3.34). It is valid asymptotically or as the data record length becomes large.

3.3 Estimator Accuracy Considerations

Before stating the CRLB theorem, it is worthwhile to expose the hidden factors that

determine how well we can estimate a parameter. Since all our information is embodied

in the observed data and the underlying PDF for that data it is not sur risin that the

estimation accuracy depen s uect Yon the PDF. For instance, we should not expect

to be able to estimate a parameter with any degree of accuracy if the PDF depends

only weakly upon that parameter, or in the extreme case, i!.the PDF does not depend

on it at all. In general, the more the PDF is influenced by the unknown parameter, the

better we shou e a e to estimate it.

Example 3.1 _ PDF Dependence on Unknown Parameter

If a single sample is observed as

x[O] = A + w[O]

where w[O] '" N(O, 0-2 ), and it is desired to estimate A, then we expect a better estimate

if 0-2 is small. Indeed, a good unbiased estimator is A. = x[O]. The variance is, of course,

just 0-2, so that the estimator accuracy improves as 0-

2

decreases. An alternative way

of viewing this is shown in Figure 3.1, where the PDFs for two different variances are

shown. They are

Pi(X[O]; A) =.)21 2 exp r- 21 2 (x[O] - A)21

21rO-i l o-i

for i = 1,2. The PDF has been plotted versus the unknown parameter A for a given

value of x[O]. If o-~ < o-~, then we should be able to estimate A more accurately based

on PI (x[O]; A). We may interpret this result by referring to Figure 3.1. If x[O] = 3 and

al = 1/3, then as shown in Figure 3.1a, the values of A> 4 are highly unlikely. To see

3.3. ESTIMATOR ACCURACY CONSIDERATIONS 29

this we determine the probability of observing x[O] in the interval [ [ ]-

[3 _ J/2, 3 +J/2] when A takes on a given value or x 0 J/2, x[0]+J/2] =

{ J J} r3+~

Pr 3 - 2" :::; x[O] :::; 3 + 2" = J3-~ Pi(U; A) du

2

which for J small is Pi (x[O] = 3; A)J. But PI (x[O] = 3' A = 4)J - .

3; A = 3)J = 1.20J. The probability of observing x[O] 'in a l~ O.OlJ, while PI (x [0] =

x[O] = 3 when A = 4 is small with respect to that h S;=- ~nterval centered about

A > 4 can be eliminated from consideration. It mthte~ - . Hence, the values ?f

the interval 3 ± 3a l = [2,4] are viable candidates ~or t~ea~~ed. tha~ values of A III

is a much weaker dependence on A. Here our . b'l d'd Fill. Figure 3.1b there

interval 3 ± 3a2 = [0,6]. via e can I ates are III the much wider

o

When the PDF is viewed as a function of th k

it is termed the likelihood function. Two exam l:su~f ~~w~ paramete: (with x fixed),

in Figure 3.1. Intuitively, the "sharpness" of &e likelih~h~o~d fu.nctlOns we:e shown

accurately we can estimate the unknown t T 0 unctIOn determllles how

ha h parame er 0 quantify thi f b

t t t e sharpness is effectively measured b th . . s no Ion 0 serve

the logarithm of the likelihood function at i~s :a~eg;t~~e .of the second derivative of

likelihood function. In Example 3 1 if .P

d ·h IS IS the curvature of the log-

., we consI er t e natural logarithm of the PDF

Inp(x[O]; A) = -In v'21ra2 - _l_(x[O]_ A)2

2a2

then the first derivative is

81np(x[0]; A) 1

8A = 0-2 (x[O] - A) (3.2)

and the negative of the second derivative becomes

_ 82

1np(x[0];A) 1

8A2 -a2 '

(3.3)

'1;.'he curvature increases as a2

decreases Since

A =x[O] has variance a2 then cor thO . 1 we already know that the estimator

, l' IS examp e

var(A.) = 1

82lnp(x[0]; A) (3.4)

8A2

and the variance decreases as the curvat .

second derivative does not depend on x[O u~~ Illcrease~. ~lthough in this example the

~easure of curvature is ], general It Will. Thus, a more appropriate

_ E [82

1np(x[O]; A)]

8A2 (3.5)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-20-2048.jpg)

![30 CHAPTER 3. CRAMER-RAO LOWER BOUND

which measures the avemge curvature of the log-likelihood function. The expectation

is taken with respect to p(x[O]; A), resultin in a function of A onl . The expectation

ac nowe ges the fact that t e i elihood function, which depends on x[O], is itself a

random variable. The larger the quantity in (3.5), the smaller the variance of the

estimator.

3.4 Cramer-Rao Lower Bound

We are now ready to state the CRLB theorem.

Theorem 3.1 (Cramer-Rao Lower Bound - Scalar Parameter) It is assumed

that the PDF p(x; 9) satisfies the "regularity" condition

E[81n~~X;9)] =0 for all 9

where the expectation is taken with respect to p(X; 9). Then, the variance of any unbiased

estimator {) must satisfy

var(8) > _~,.....1---:-~-=

-_ [82

Inp(X;9)]

E 892

(3.6)

where the derivative is evaluated at the true value of 9 and the expectation is taken with

respect to p(X; 9). Furthermore, an unbiased estimator may be found that attains the

bound for all 9 if and only if •

8Inp(x;6} =I(9)(g(x) _ 9}

89

(3.7)

for some functions 9 and I. That estimator which is the MVU estimator is {) = x),

and the minimum variance is 1 1(9).

The expectation in (3.6) is explicitly given by

E [8

2

1n p(X; 9}] = J8

2

1np(x; 9) ( . 9) d

892 892 P X, X

since the second derivative is a random variable dependent on x. Also, the bound will

depend on 9 in general, so that it is displayed as in Figure 2.5 (dashed curve). An

example of a PDF that does not satisfy the regularity condition is given in Problem

3.1. For a proof of the theorem see Appendix 3A.

Some examples are now given to illustrate the evaluation of the CRLB.

Example 3.2 - CRLB for Example 3.1

For Example 3.1 we see that from (3.3) and (3.6)

for all A.

3.4. CRAMER-RAO LOWER BOUND 31

Thus, no unbiased estimator can exist wpose variance is lower than a2 for even a single

value of A. But III fa~t we know tha~ if A - x[O], then var(A} = a2 for all A. Since x[O]

is unbiasea and attaIns the CRLB, It must therefore be the MVU estimator. Had we

been unable to guess that x[O] would be a good estimator, we could have used (3.7).

From (3.2) and (3.7) we make the identification

9

I(9}

g(x[O])

A

1

a2

= x[O)

so that (3.7) is satisfied. Hence, A= g(x[O]) = x[O] is the MVU estimator. Also, note

that var(A) = a2

= 1/1(9), so that according to (3.6) we must have

We will return to this after the next example. See also Problem 3.2 for a generalization

to the non-Gaussian case. <>

Example 3.3 - DC Level in White Gaussian Noise

Generalizing Example 3.1, consider the multiple observations

x[n) = A +w[n) n = 0, 1, ... ,N - 1

where w[n] is WGN with variance a2

. To determine the CRLB for A

p(x; A)

Taking the first derivative

8lnp(x;A)

8A

N-l 1 [1 ]

11V2rra2 exp - 2a2 (x[n]- A?

1 [1 N-l ]

(2rra2)~ exp - 2a2 ~ (x[n]- A)2 .

8 [ 1 N-l ]

- -In[(2rra2)~]- - "(x[n]- A)2

8A 2a2 L..

n=O

1 N-l

2' L(x[n]- A)

a n=O

N

= -(x-A)

a2 (3.8)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-21-2048.jpg)

![32 CHAPTER 3. CRAMER-RAO LOWER BOUND

where x is the sample mean. Differentiating again

82

Inp(x;A) N

8A2 =- q2

and noting that the second derivative is a constant, ~ from (3.6)

(3.9)

as the CRLB. Also, by comparing (3.7) and (3.8) we see that the sample mean estimator

attains the bound and must therefore be the MVU estimator. Also, once again the

minimum variance is given by the reciprocal of the constant N/q2 in (3.8). (See also

Problems 3.3-3.5 for variations on this example.) <>

We now prove that when the CRLB is attained

where

. 1

var(8) = /(8)

From (3.6) and (3.7)

and

var(9) __-..".-."...,--1-,..---:-:-:-

-_ [82Inp(X; 0)]

E 802

8Inp(x; 0) = /(0)(9 _ 0).

88

Differentiating the latter produces

8

2

Inp(x; 0) = 8/(0) ({) _ 0) _ /(0)

802

80

and taking the negative expected value yields

and therefore

-E [82

In p(X; 0)]

802

- 8/(0) [E(9) - 0] + /(0)

80

/(0)

A 1

var(O) = /(0)'

In the next example we will see that the CRLB is not always satisfied.

(3.10)

3.4. CRAMER-RAO LOWER BOUND

Example 3.4 - Phase Estimation

Assume that we wish to estimate the phase ¢ of a sinusoid embedded in WGN or

x[n] =Acos(21lJon +¢) + wIn] n = 0, 1, ... , N - 1.

33

The ampiitude A and fre uenc 0 are assumed known (see Example 3.14 for the case

when t ey are unknown). The PDF is

1 {I N-l }

p(x; ¢) = Ii. exp --2

2 E [x[n]- Acos(21lJon +4»f .

(27rq2) 2 q n=O

Differentiating the log-likelihood function produces

and

-

8Inp(x; ¢)

84>

1 .'-1

-2 E [x[n]- Acos(27rfon + cP)]Asin(27rfon +¢)

q n=O

A N-l A

- q2 E [x[n]sin(27rfon +4» - "2 sin(47rfon + 24»]

n=O

821 (¢) A N-l

n;2

X

; = -2 E [x[n] cos(27rfon +¢) - Acos(47rfon + 2¢)].

¢ q n=O

Upon taking the negative expected value we have

A N-l

2 E [Acos2

(27rfon + ¢) - A cos(47rfon + 2¢)]

q n=O

A2N-l[11 ]

2" E -+ - cos(47rfon + 2¢) - cos(47rfon +2¢)

q n=O 2 2

NA2

2q2

since

1 N-l

N E cos(47rfon + 2¢) ~ 0

n=O

for 10 not near 0 or 1/2 (see Problem 3.7). Therefore,

In this example the condition for the bound to hold is not satisfied. Hence, a phase

estimator does not eXIst whIch IS unbiased and attains the CRLB. It is still possible,

however, that an MVU estimator may exist. At this point we do not know how to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-22-2048.jpg)

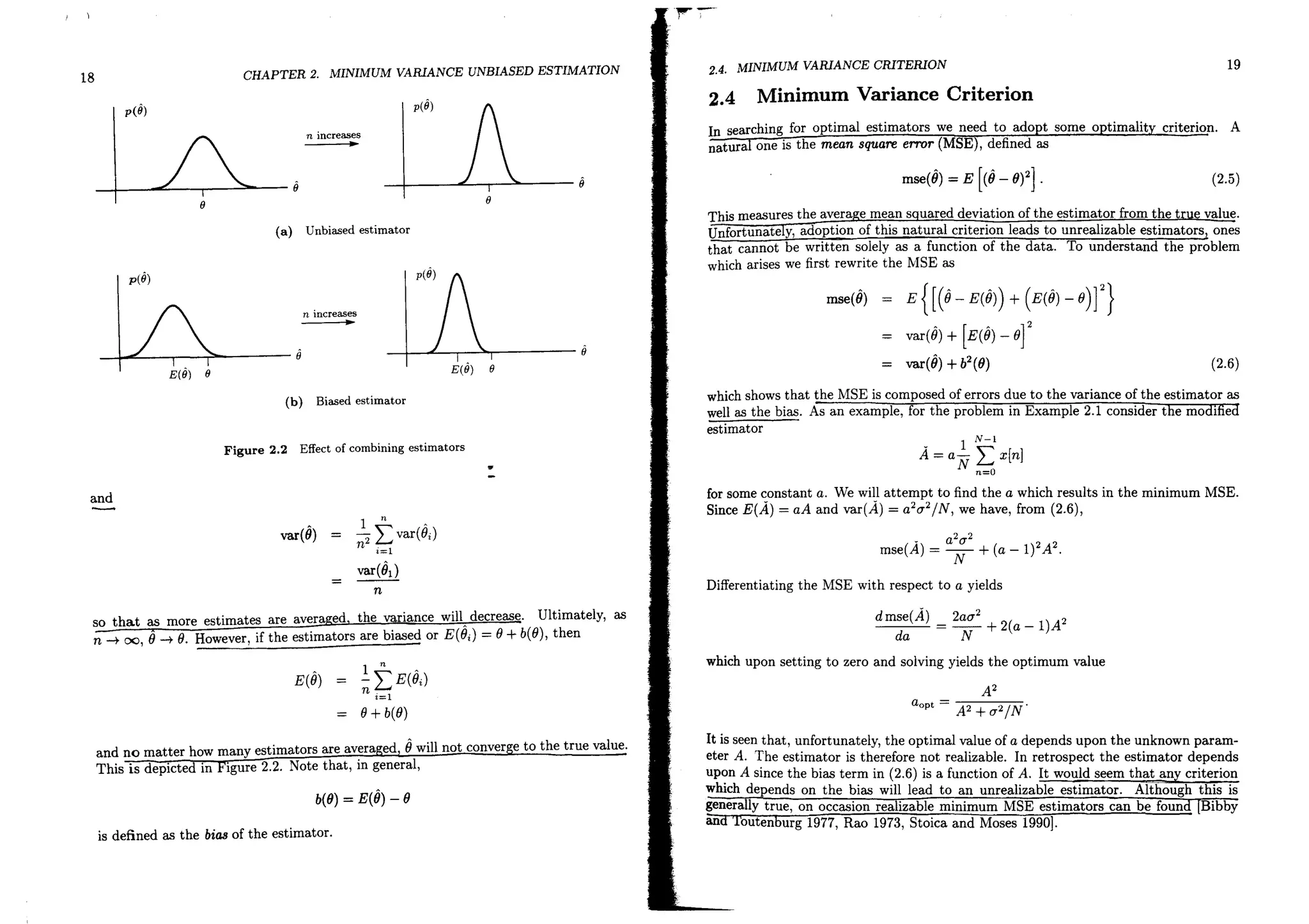

![34

................ _...........

93

................

•• 91 and CRLB

-------4--------------------- 0

(a) (h efficient and MVU

CHAPTER 3. CRAMER-RAO LOWER BOUND

var(9)

..............................

-------+-------------------- e

(b) 81 MVU but not efficient

Figure 3.2 Efficiency VB. minimum variance

determine whether an MVU estimator exists, and if it does, how to find it. The theory

of sufficient statistics presented in Chapter 5 will allow us to answer these questions.

o

An estimator which is unbiased and attains the CRLB, as the sample mean estimator

in Example 3.3 does, IS said to be efficient in that it efficiently uses the data. An MVU

estimator rna or may not be efficient. For instance, in Figure 3.2 the variances of all

possible estimators or purposes of illustration there are three unbiased estimators)

are displayed. In Figure 3.2a, 81 is efficient in that it attains the CRLB. Therefore, it

is also the MVU estimator. On the other hand, in Figure 3.2b, 81 does not attain the

CRLB, and hence it is not efficient. However, since its varianoe is uniformly less than

that of all other unbiased estimators, it is the MVU estimator.-

The CRLB given by (3.6) may also be expressed in a slightly different form. Al-

though (3.6) is usually more convenient for evaluation, the alternative form is sometimes

useful for theoretical work. It follows from the identity (see Appendix 3A)

(3.11)

so that

(3.12)

(see Problem 3.8).

The denominator in (3.6) is referred to as the Fisher information /(8) for the data

x or

(3.13)

As we saw previously, when the CRLB is attained, the variance is the reciprocal of the

Fisher information. Int"iirtrvely, the more information, the lower the bound. It has the

essentiaI properties of an information measure in that it is

3.5. GENERAL CRLB FOR SIGNALS IN WGN 35

1. nonnegative due to (3.11)

2. additive for independent observations.

The latter property leads to the result that the CRLB for N lID observations is 1 N

times t a, or one 0 servation. To verify this, note that for independent observations

N-I

lnp(x; 8) = L lnp(x[n]; 8).

n==O

This results in

-E [fJ2 lnp(x; 8)] = _ .~I E [fJ2ln p(x[n];8)]

[)82 L., [)82

n=O

and finally for identically distributed observations

/(8) = Ni(8)

where

i(8) = -E [[)2In~~[n];8)]

is the Fisher information for one sam Ie. For nonindependent samples we might expect

!!J.at the in ormation will be less than Ni(8), as Problem 3.9 illustrates. For completely

dependent samples, as for example, x[O] = x[l] = ... = x[N-1], we will have /(8) = i(8)

(see also Problem 3.9). Therefore, additional observations carry no information, and

the CRLB will not decrease with increasing data record length.

3.5 General CRLB for Signals

in White Gaussian Noise

Since it is common to assume white Gaussian noise, it is worthwhile to derive the

CRLB for this case. Later, we will extend this to nonwhite Gaussian noise and a vector

parameter as given by (3.31). Assume that a deterministic signal with an unknown

p'arameter 8 is observed in WGN as

x[n] = s[nj 8] +w[n] n = 0, 1, ... ,N - 1.

The dependence of the signal on 8 is explicitly noted. The likelihood function is

p(x; 8) = N exp - - L (x[n] - s[nj 8])2 .

1 {I N-I }

(211"172).. 2172 n=O

Differentiating once produces

[)lnp(xj8) = ~ ~I( [ ]_ [ . ll]) [)s[nj 8]

[)8 172 L., X n s n, u [)8

n=O](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-23-2048.jpg)

![36 CHAPTER 3. CRAMER-RAO LOWER BOUND

and a second differentiation results in

02lnp(x;(J) =2- ~l{( []_ [.(J])8

2

s[n;(J]_ (8S[n;(J])2}.

8(J2 (12 L...J x n s n, 8(J2 8(J

n=O

Taking the expected value yields

E (82

Inp(x; (J)) = _2- ~ (8s[n; 0]) 2

802 (12 L...J 80

n=O

so that finally

(3.14)

The form of the bound demonstrates the importance of the si nal de endence on O.

Signals that c ange rapidly as t e un nown parameter changes result in accurate esti-

mators. A simple application of (3.14) to Example 3.3, in which s[n; 0] = 0, produces

a CRLB of (12/N. The reader should also verify the results of Example 3.4. As a final

example we examine the problem of frequency estimation.

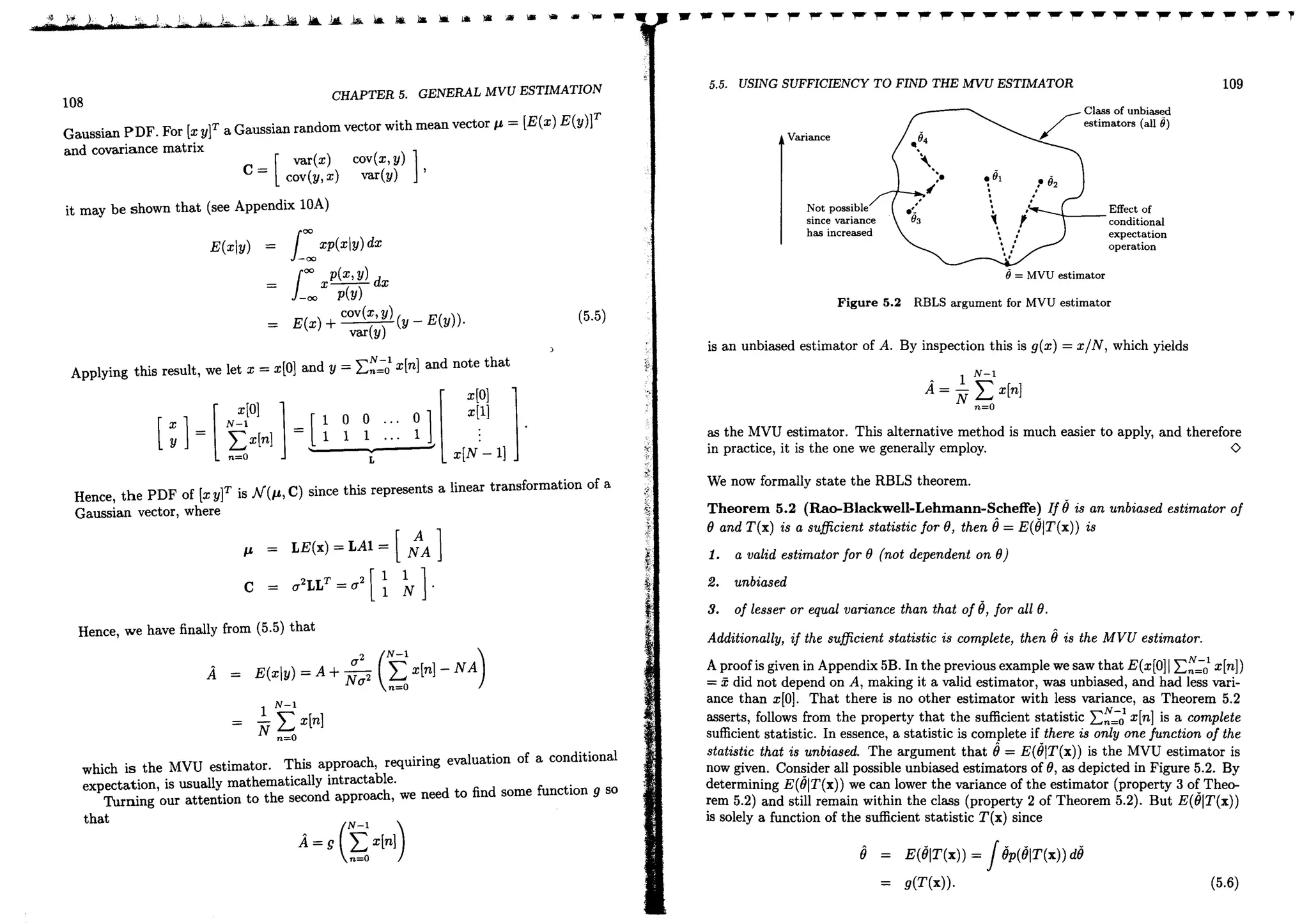

Example 3.5 - Sinusoidal Frequency Estimation

We assume that the signal is sinusoidal and is represented as

s[n; fo] =A cos(271Ion + cP)

1

0< fo < 2

where-the amplitude and phase are known (see Example 3.14 for the case when they

are unknown). From (3.14) the CRLB becomes

(12

var(jo) ~ -N---l------- (3.15)

A2 L [21Tnsin(21Tfon + cP)]2

n=O

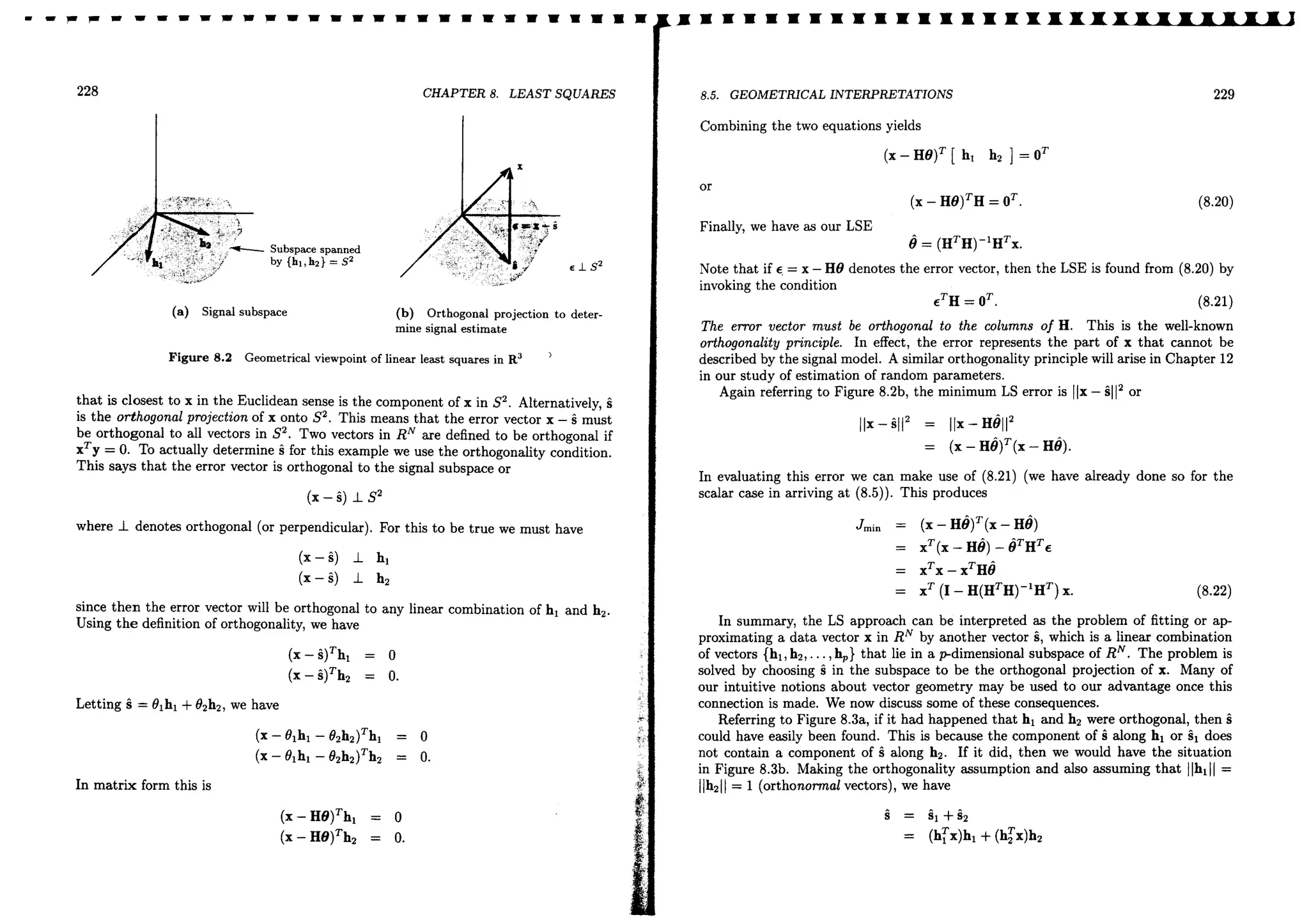

The CRLB is plotted in Figure 3.3 Vf>TSUS frequency for an SNR of A2

/(l2 = 1, a data

record length of N = 10, and a phase of cP = O. It is interesting to note that there

appea.r to be preferred frequencies (see also Example 3.14) for an approximation to

(3.15)). Also, as fo -+ 0, the CRLB goes to infinity. This is because for fo close to zero

a slight change in frequency will not alter the signal significantly. 0

3.6. TRANSFORMATION OF PARAMETERS

5.0-:-

-g 4.5-+

j 4.0~

~ 3.5~

Ja 3.0~

~ I

~ 2.5-+

~ 2.0~

'"

...

C) 1.5-+

I

1.o-l.

1

~'>Lr----r---r---r-----t----''---r---r---r:>.L----t--

0.00 0.05 0.10 0.15 0.20 0.25 0.30 0.35 0.40 0.45 0.50

Frequency

Figure 3.3 Cramer-Rao lower bound for sinusoidal frequency estimation

3.6 Transformation of Parameters

37

It fre uentl occurs in practice that the parameter we wish to estimate is a function

o some more fun amenta parameter. or mstance, in Example 3.3 we may not be

interested in the sign of A but instead may wish to estimate A2 or the power of the

signal. Knowing the CRLB for A, we can easily obtain it for A2 or in general for ~

function of A. As shown in Appendix 3A, if it is desired to estimate ex = g(0), then the

CRLBi§

(3.16)

For the present example this becomes ~ = g(A) = A2 and

(A

2) > (2A)2 = 4A2(12

var - N/(l2 N' (3.17)

Note that in using (3.16) the CRLB is expressed in terms of O.

We saw in Example 3.3 that the sample mean estimator was efficient for A. It might

be sUj)OSed that x2 is efficient for A2. To uickl dispel this notion we first show that

is not even an unbiased estimator. Since x ""' (A, (I

(12

= E2(:C) +var(x) = A2 + N

1= AZT' (3.18)

Hence, we immediately conclude that the efficiency of an estimator is destroyed by a

ftonlinear transformatioTil That it is maintained for linear (actually affine) transfor-

mations is easily verified. Assume that an efficient estimator for 0 exists and is given](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-24-2048.jpg)

![38 CHAPTER 3. CRAMER-RAO LOWER BOUND

'by O. It is desired to estimate g{O) = aO + b. As our estimator of g(O), we choose

.#) = g(0) = aO + b. Then,

E(a8 +b) = aE(8) +b= a8 +b>

= g(8} ,

so that g(O) is unbiased. The CRLB for g(O), is from (3.16),

(

8g )2

;:;;.j~

- I(O)

var(g(8))

( 8~~)) 2 var(0)

a2

var(8)O

But var{g(O)) = var(aO + b) = a2

var(O), so that the CRLB is achieved.

Althou h efficienc is reserved onl over linear transformations, it is approximatel

maintained over nonlinear transformations if the data record is large enoug. IS as

great practical significance in that we are frequently interested in estimating functions

of parameters. To see why this property holds, we return to the previous example of

estimating A2 by x2. Although x2is biased, we note from (3.18) that x2is asymptotically

unbiased or unbiased as N ~ 00. Furthermore, since x '" N(~0'2 IN), we can evaluate

tIle variance

var(x2

) =E(x4

) - E2(x2

}J

by using the result that if ~ '" N(J,L, 0'2), then

and therefore

E(e) = p.2 +q2, J

E(~4) = p.4 +6p.2q2 +3q~/

var(e) E(e) - E2

(e)

4J,L20'2 + 20'4.

For our problem we have then

-

Hence, as N ~ 00, the variance approaches 4A2

0'2 IN, the last term in (3.19) converging

to zero faster than the first, But this is just the CRLB as given by (3.17). Our assertion

that x2is an asymptotically efficient estimator of A2

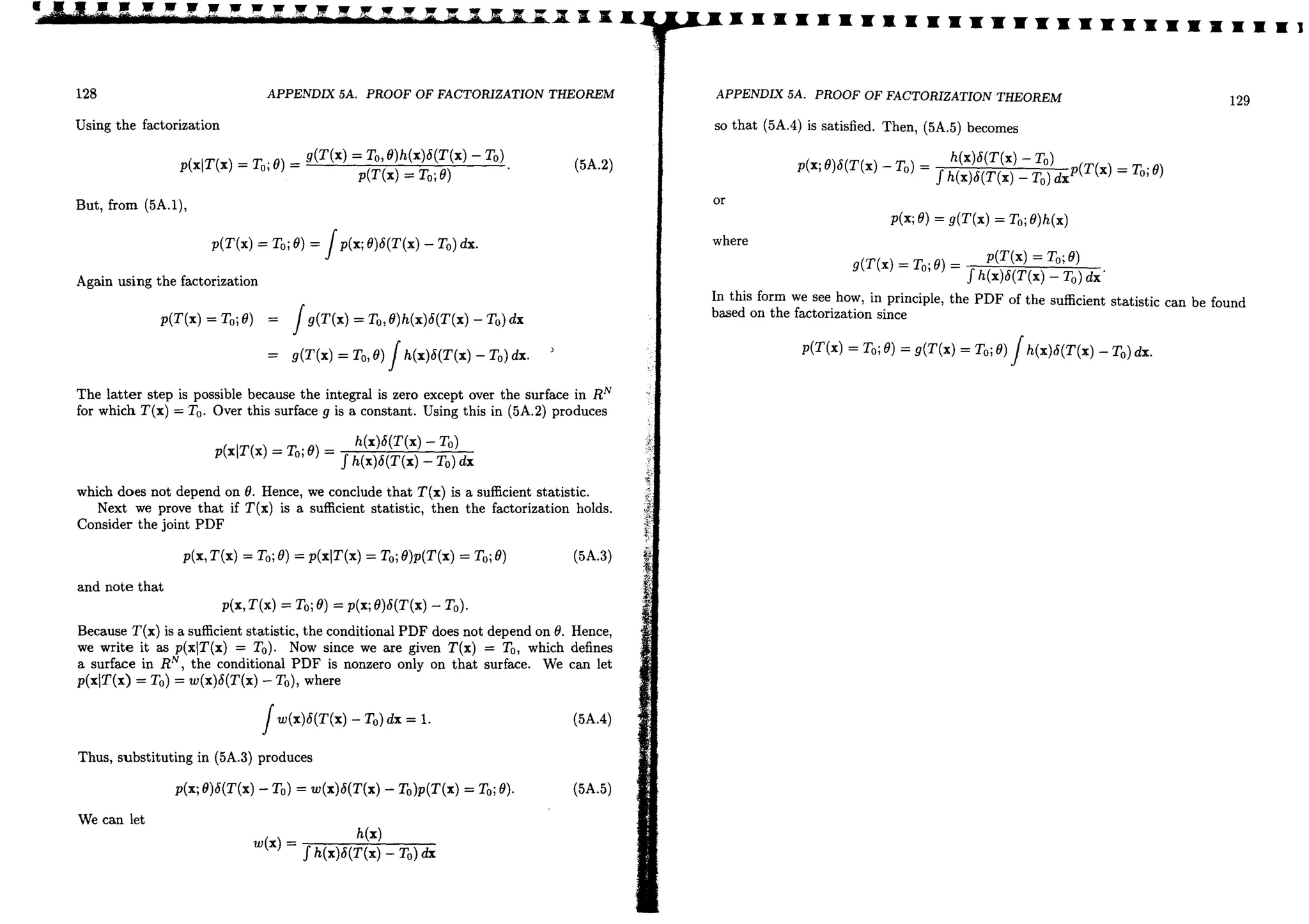

is verified. Intuitively, this situation

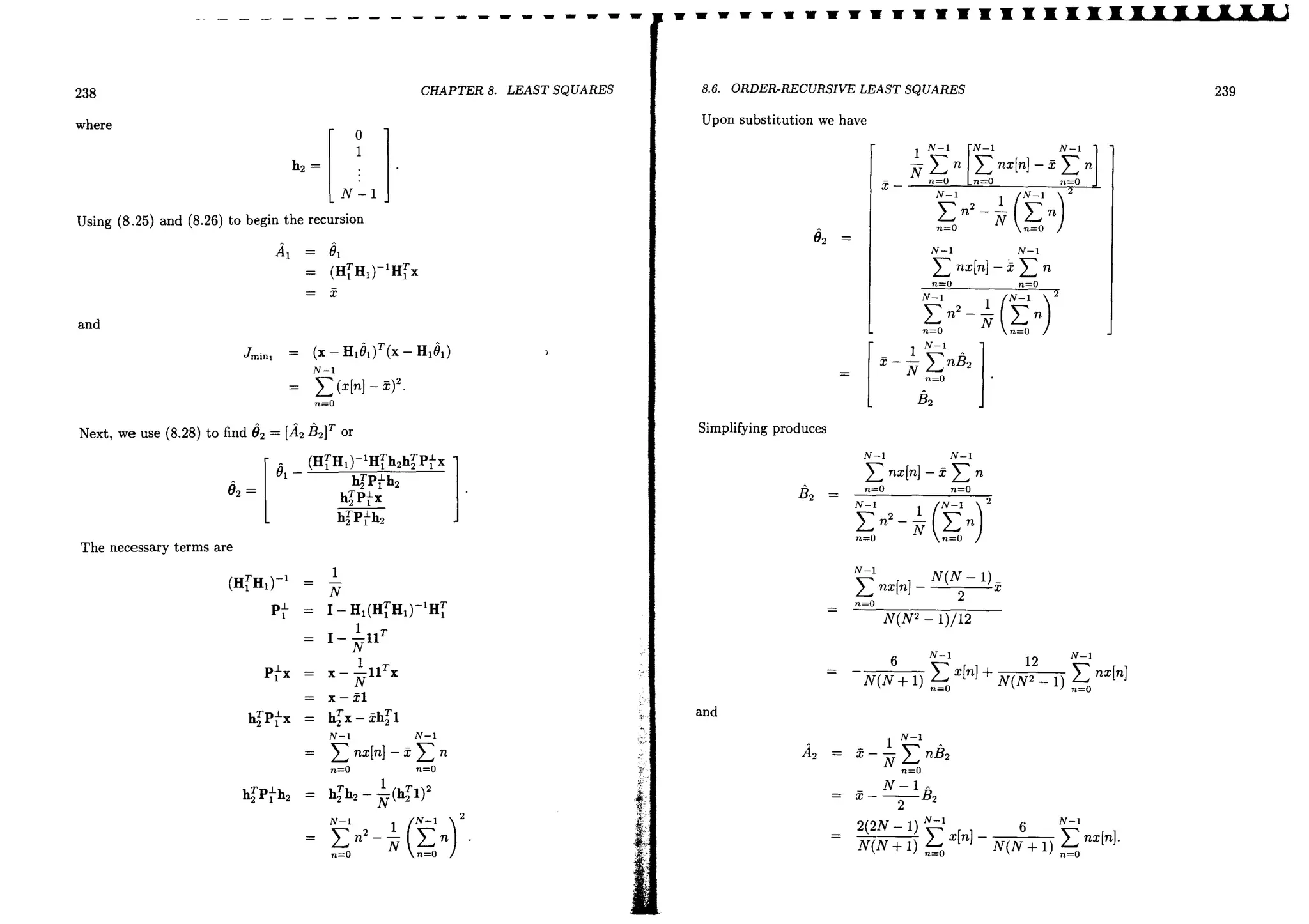

occurs due to the statistical linearity of the transformation, as illustrated in Figure 3.4,

As N increases, the PDF of xbecomes more concentrated about the mean A. Therefore,

EXTENSION TO A VECTOR PARAMETER

3.7.

39

~~----------~~--~------- x

A-~ A

-IN

(a) Small N

30"

A+-

-IN

A-~ A

-IN

(b) Large N

Figure 3.4 Statistical linearity of nonlinear transformations

30"

A+-

-IN

the values of x that are observed lie in a small interval about x = A (the ±3 standard

deviation interval is displayed). Over this small interval the nonlinear transformation

is approximately linear. Therefore, the transformation may be replaced by a linear one

since a value of x in the nonlinear region rarely occurs. In fact, if we linearize g about

A, we have the approximation

dg(A) ,",

g(x) ~ g(A) + d}i(x - A)."

It follows that, to within this approximation,

E[g(x)] = g(A) = A2

or the estimator is unbiased (asymptotically). Als<?!...

var[g(x)] [

d9(A)]2 (-)

dA var x

(2A)20'2

N

4A20'2

N

so that the estimator achieves the CRLB (asymptotically). Therefore, it is asymp-

totically efficient. This result also yields insight into the form of the CRLB given by

(3.16).

3.7 Extension to a Vector Parameter

We now extend the results of the previous sections to the case where we wish to estimate

a vector parameter (} = [01 02 " • 8p j1:: We will assume that the estimator (J is unbiased](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-25-2048.jpg)

![·w CHAPTER 3. CRAMER-RAO LOWER BOUND

:IS defined in Section 2.7. The vector parameter CRLB will allow us to place a bound

"ll the variance of each element. As derived in Appendix 3B, the CRLB is found as the

.i. i] element of the inverse of a matrix or

var(6i) ~ [rl(9)]ii . (3.20)

where 1(8) is the p x p Fisher information matrix. The latter is defined by

[1(8)] .. = -E [82

lnp(X;8)] v

" 88;l}8j it

(3.21)

f,)r 1= 1,2, ... ,p;j = 1,2, .... In evaluating (3.21) the true value of 8 is used.

'ote t at in t e scalar case (p = 1), = J(O) and we ave the scalar CRLB. Some

,'xamples follow.

Example 3.6 - DC Level in White Gaussian Noise (Revisited)

"e now extend Example 3.3 to the case where in addition to A the noise variance a 2

:~ also unknown. The parameter vector is 8 = [Aa2

f, and hence p = 2. The 2 x 2

Fisher information matrix is

_E[82

ln

p

(x;8)] 1

8A8a2

-E [82

lnp(X; 8)] .

8 22

a ..

It is clear from (3.21) that the matrix is symmetric since the order of partial differenti-

.Ilion may be interchanged and can also be shown to be positive definite (see Problem

;UO). The log-likelihood function is, from Example 3.3,

N N 1 N-l

lnp(x' 8) = --ln271" - -lna2

- - L (x[n]- A)2.

, 2 2 2a2

n=O

l'he derivatives are easily found as

8 lnp(x; 8)

8A

8 lnp(x; 8)

8a2

82 lnp(x; 8)

8A2

82

lnp(x; 8)

8A8a2

82

lnp(x;8)

8a22

1 N-l

"2 L(x[n]- A)

a n=O

N 1 N-l

-- + - "(x[n]- A)2

2a2 2a4 L

n=O

N

a2

1 N-l

-- '" (x[n]- A)

a4 L

n=O

N 1 N-l

-- - - "(x[n]- A)2.

2a~ a6 L

n=O

3.7. EXTE.VSION TO A VECTOR PARAMETER 41

Upon taking tne negative expectations, the Fisher information matrix becomes

1(8) = [~ ~] .

2a4

Although not true in general, for this example the Fisher information matrix is diagonal

and hence easily inverted to yield

0

var(A)

a-

~

N

var(d2

)

2a4

~

N

Note that the CRLB for A. is the same as for the case when a2

is known due to the

diagonal nature of the matrix. Again this is not true in general, as the next example

illustrates. 0

Example 3.7 - Line Fitting

Consider the problem of line fitting or given the observations

x[n] = A + Bn + w[n] n = 0, 1, ... , N - 1

where w[n] is WGN, determine the CRLB for the slope B and the intercept A. .The

parameter vector in this case is 8 = [AB]T. We need to first compute the 2 x 2 FIsher

information matrix,

1(8) =

[

_ [82

ln p(X;8)]

E 8A2

_ [82

ln p(x;8)]

E .8B8A

The likelihood function is

p(x; 8) = N exp --2 L (x[n] - A - Bn)2

1 {I N-l }

(271"a2

) "2 2a n=O

from which the derivatives follow as

8lnp(x;8)

8A

8lnp(x;8)

8B

1 N-l

- "(x[n]- A - Bn)

a2 L

n=O

1 N-l

- "(x[n]- A - Bn)n

a2 L

n=O](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatisticalsignalprocessing-estimationtheory-kay-230513154707-1f7652e0/75/Fundamentals-Of-Statistical-Signal-Processing-Estimation-Theory-Kay-pdf-26-2048.jpg)

![42

CHAPTER 3. CRAMER-RAO LOWER BOUND

and

o2Inp(x; 9)

OA2

o2Inp(x; 9)

oA8B

o2Inp(x; 9)

OB2

N

0'2

1 N-I

- 0'2 L n

n=O

1 N-I

- 0'2 L n

2

.

n=O

Since the second-order derivatives do not depend on x, we have immediately that

[ N~' 1

1(9)

1 N 2:>

n-O

0'2 %n ~n2

~ :'[

N

N(N -1)

2

N(N -1) N(N - 1)(2N - 1)

2 6

where we have used the identities

N-I

Ln

n=O

Inverting the matrix yields

N(N -1)

2

N(N - 1)(2N - 1)

6

[

2(2N -1)

1-1(9) = 0'2 _N(N: 1) N(:+ 1) j.

12

N(N2 - 1)

N(N + 1)

It follows from (3.20) that the CRLB is

var(A)

2 2(2N - 1)0'2

N(N + 1)

var(.8) >

N(N2 - 1)'

1

(3.22)

3.7. EXTENSION TO A VECTOR PARAMETER 43

x[nJ x[nJ

4-

3 3-

2 2-

n

1 -

1

n

2 3 4 2 3 4