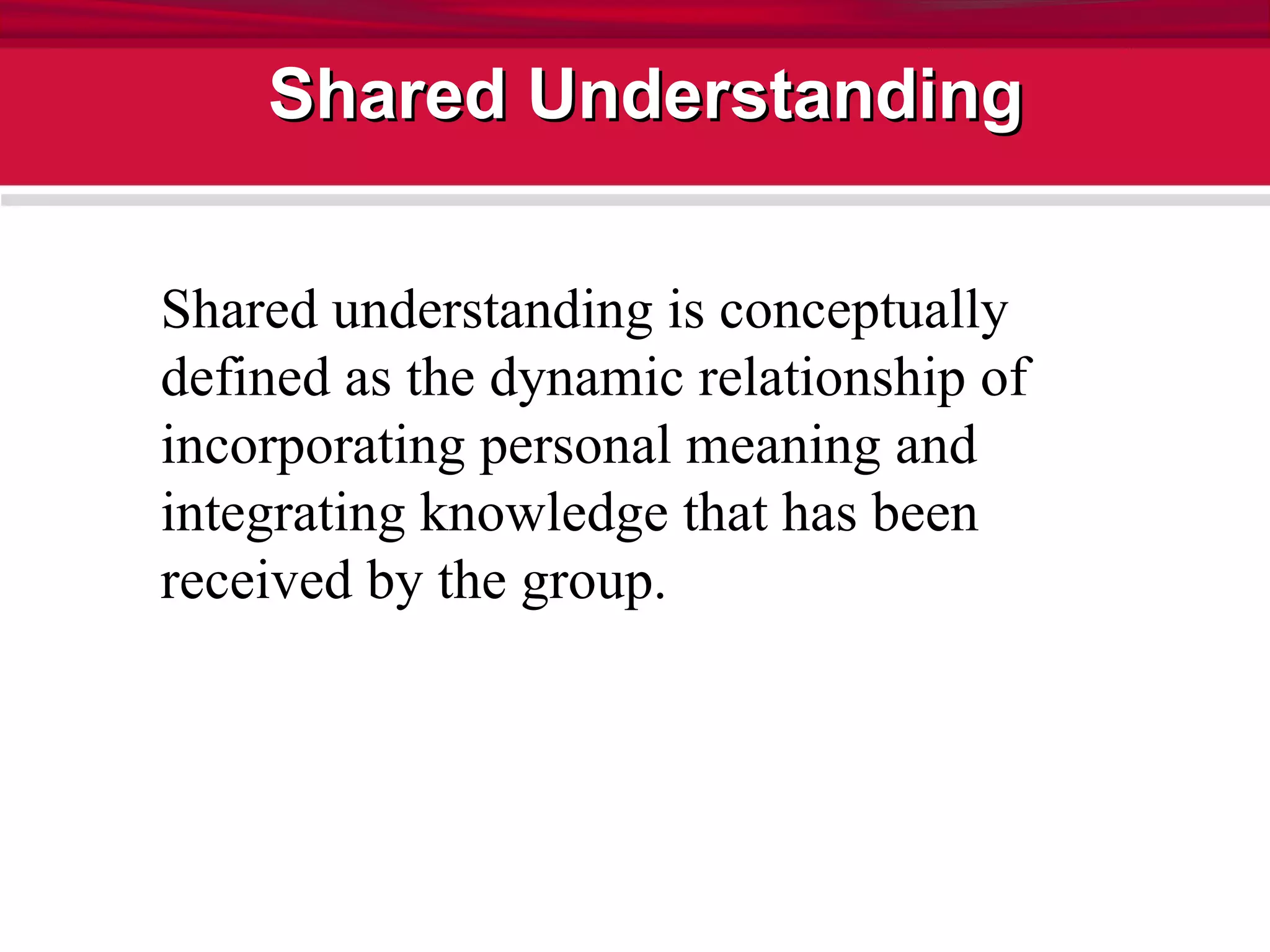

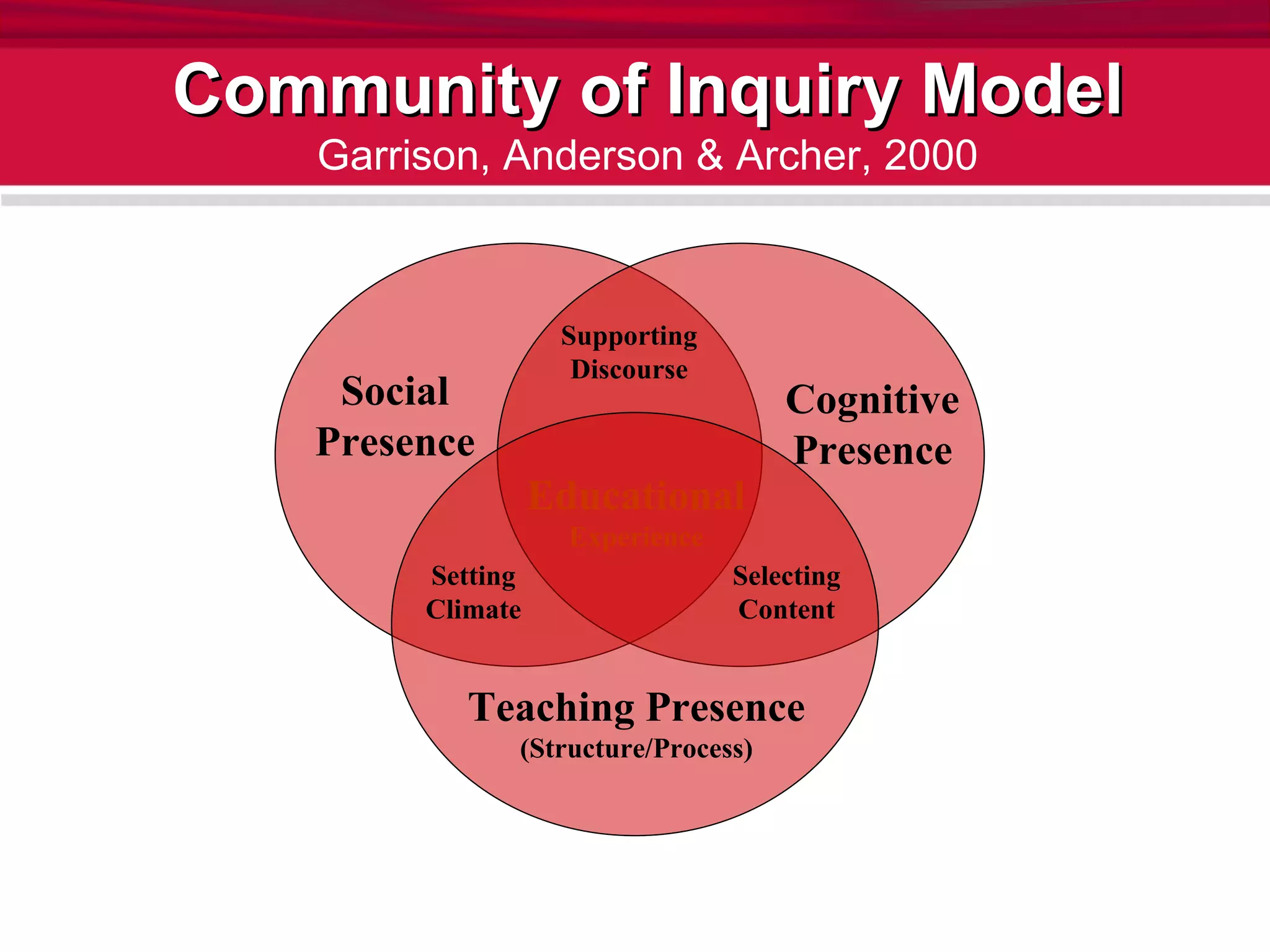

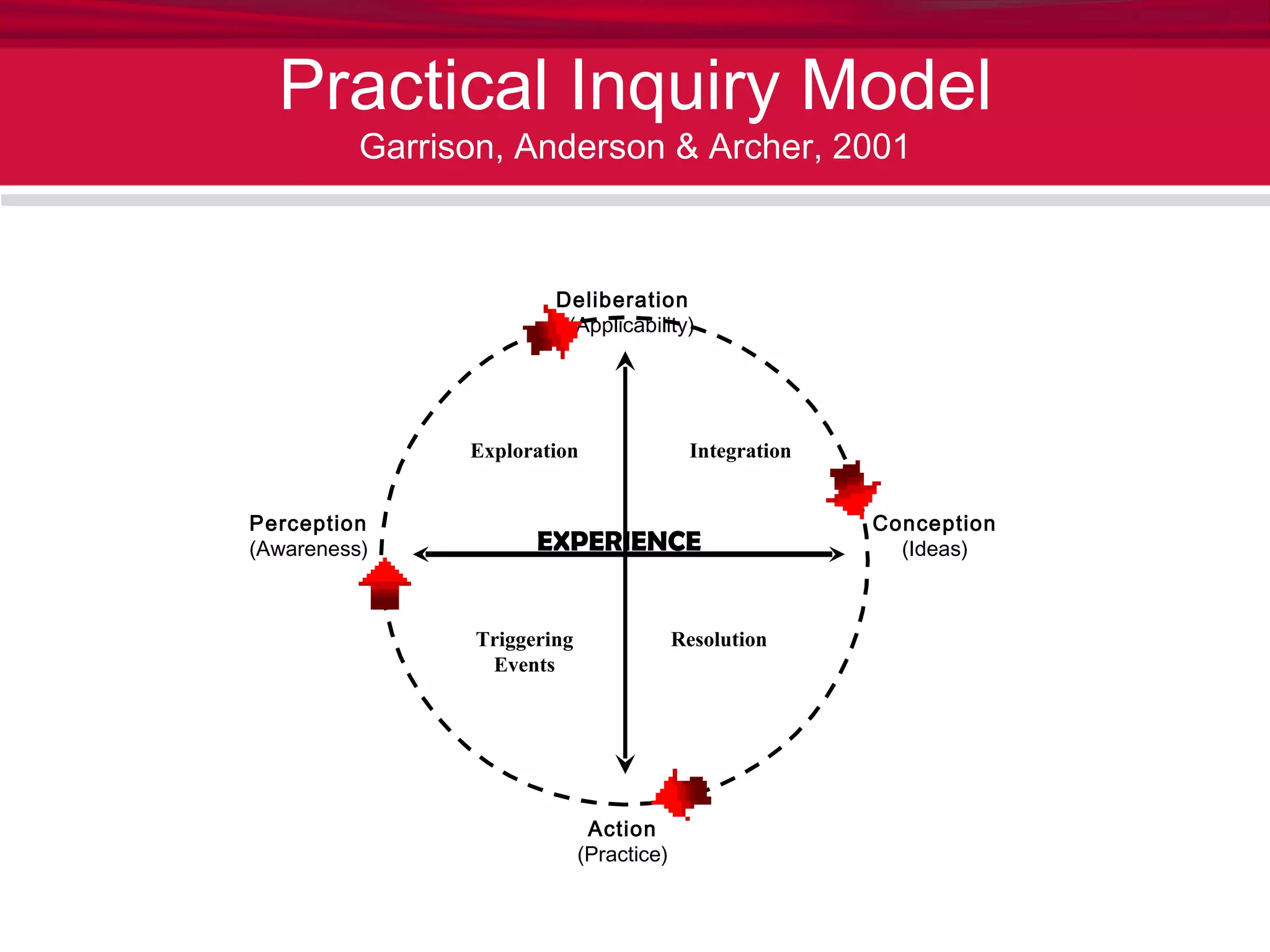

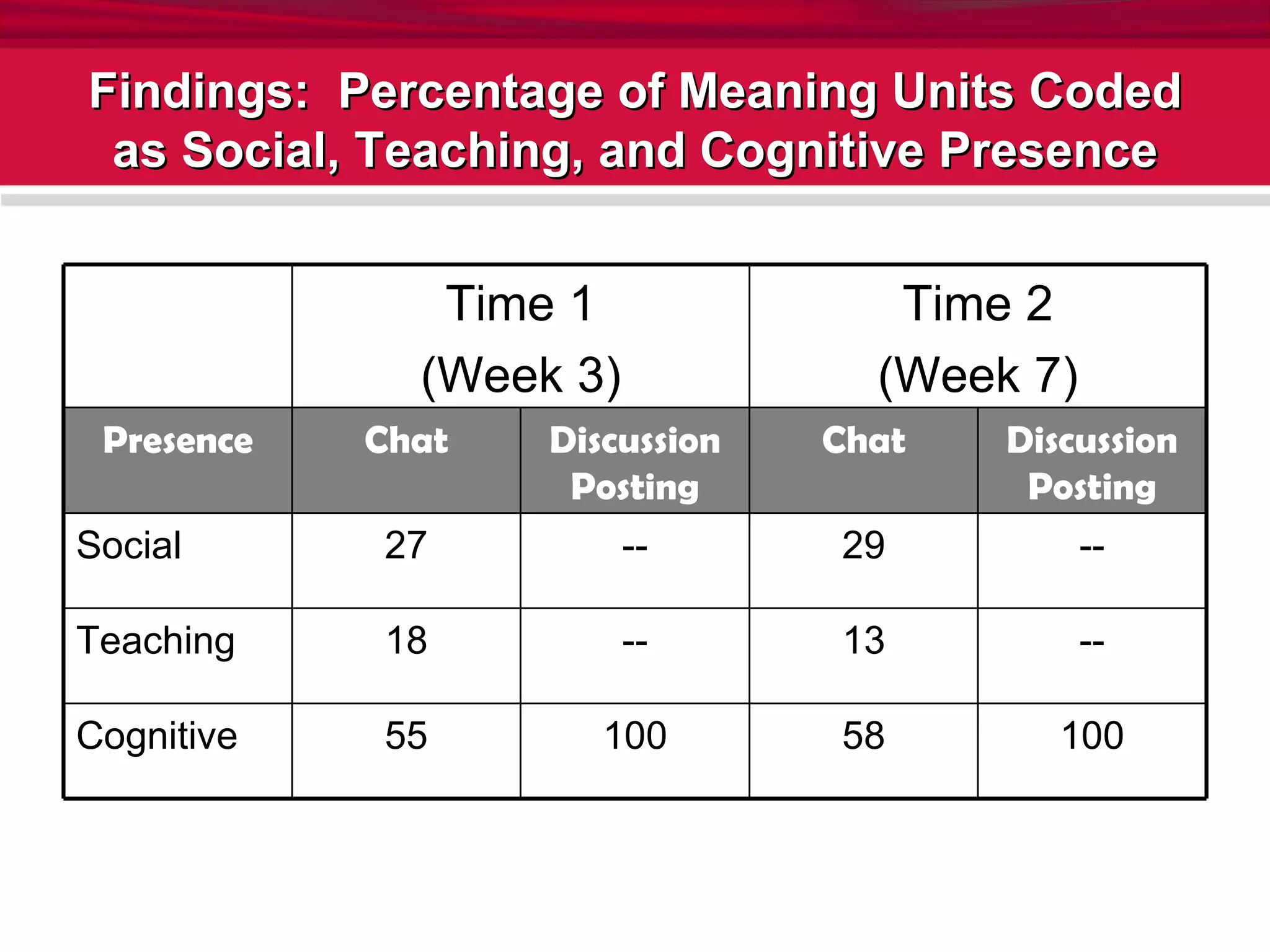

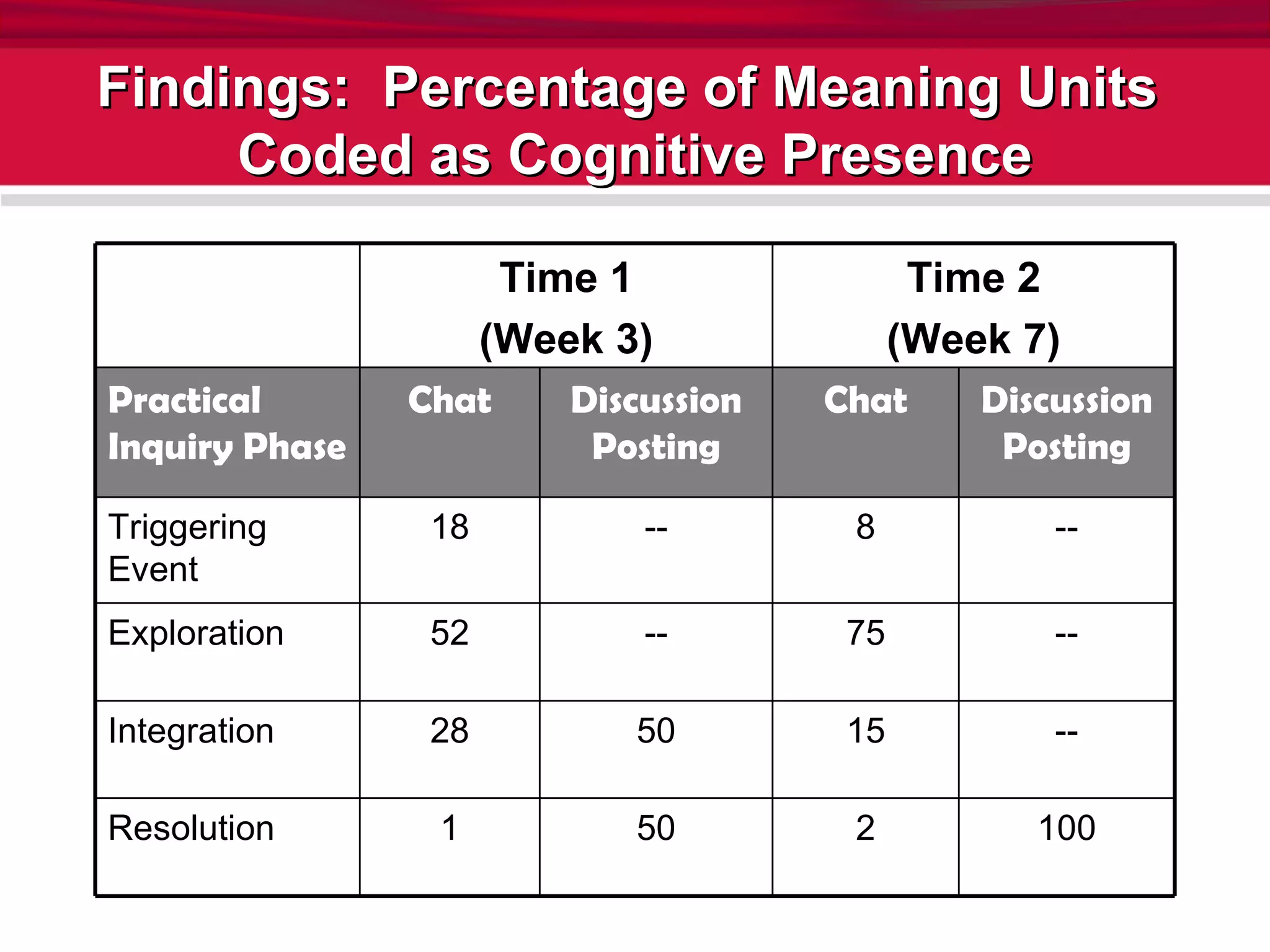

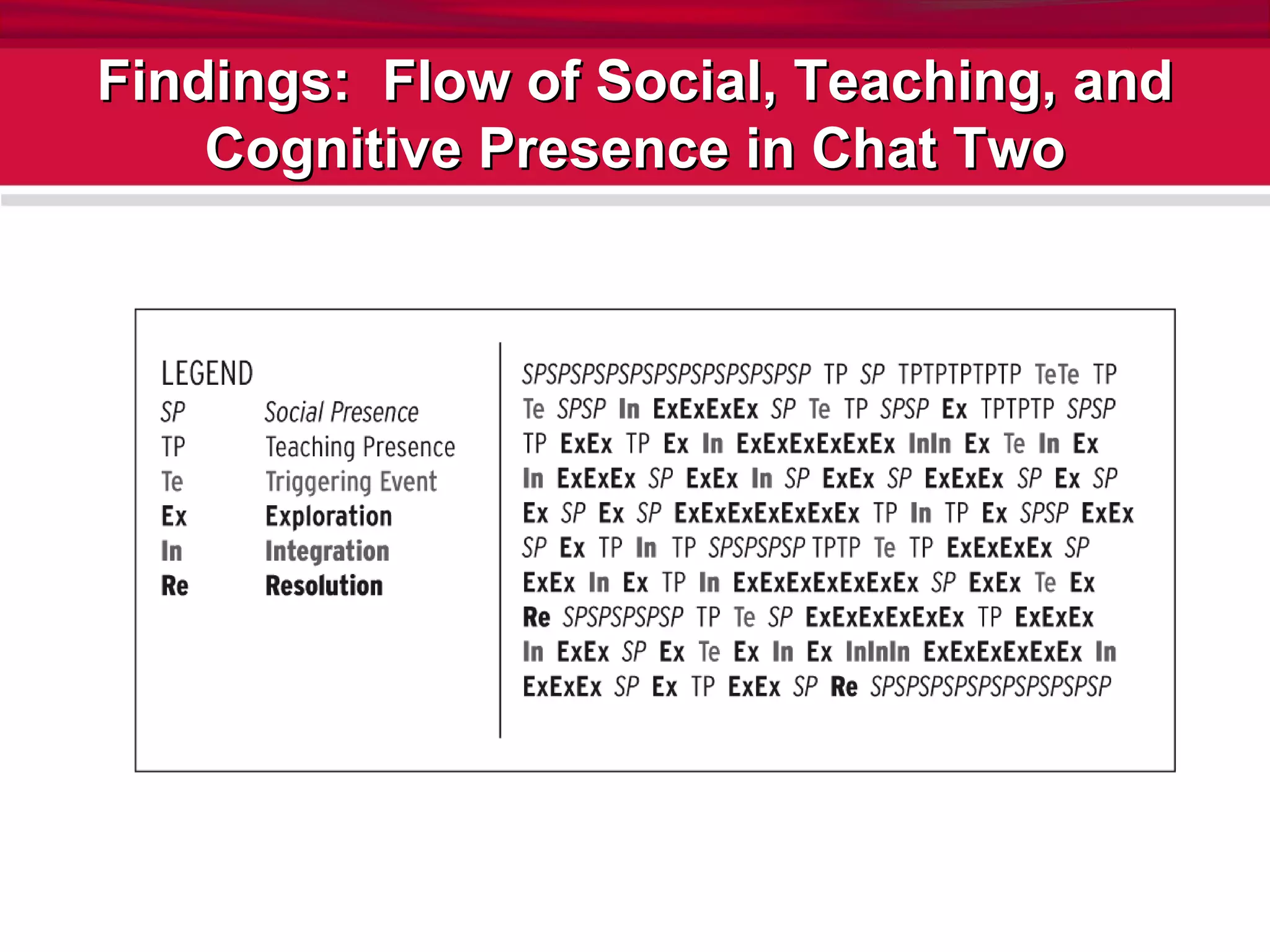

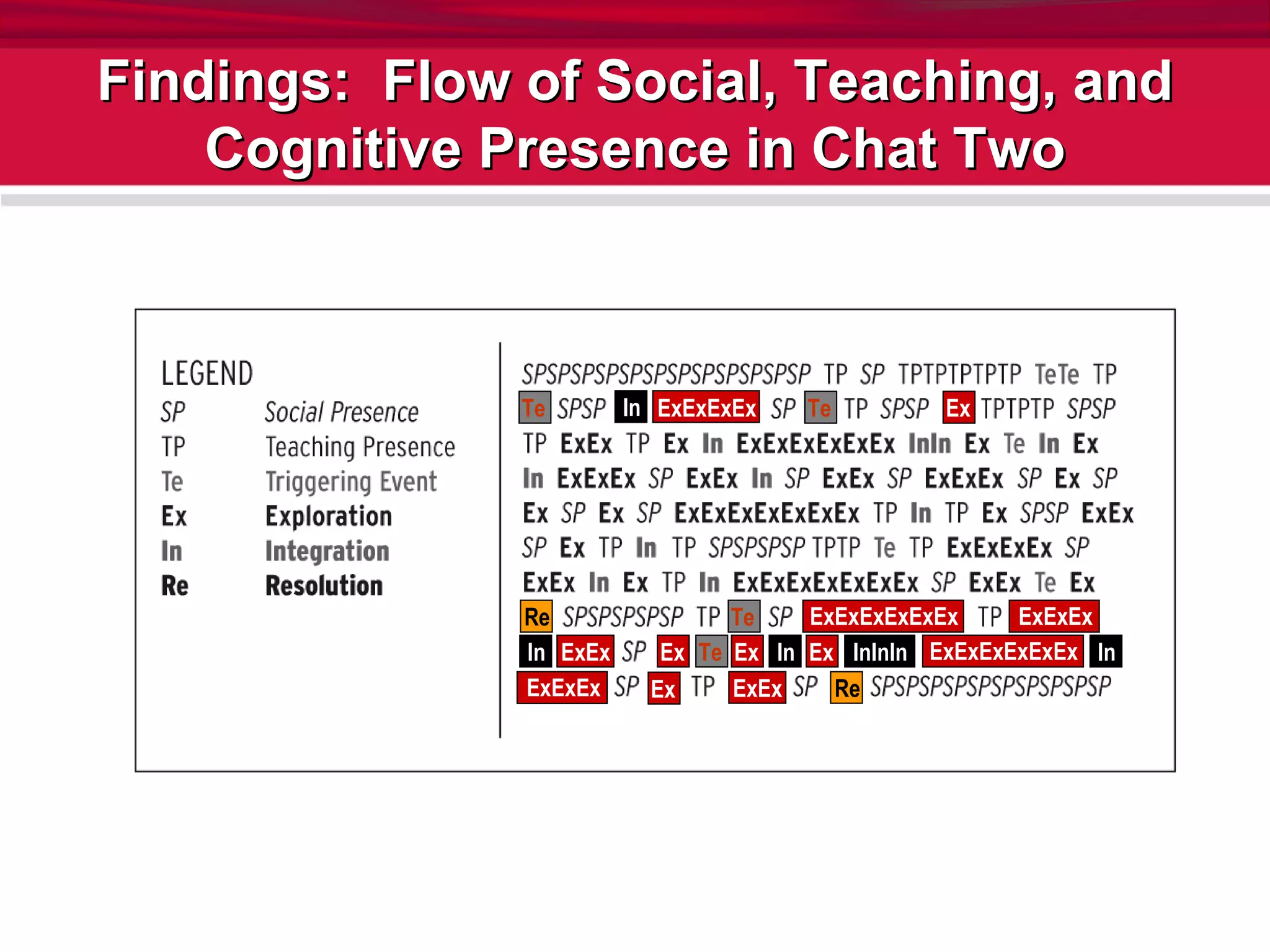

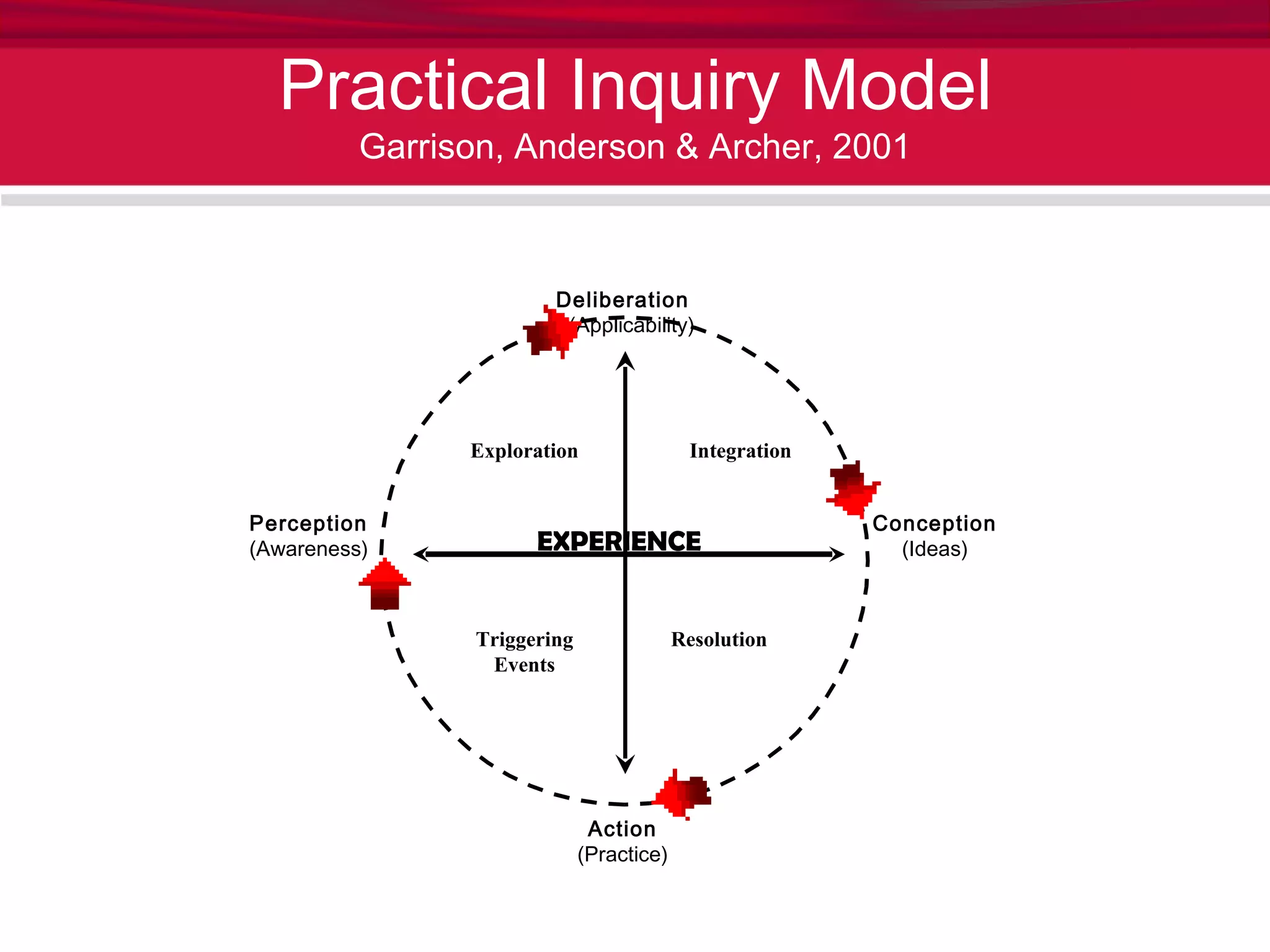

The study investigates how shared understanding develops in chat learning environments, focusing on the dynamic interplay between personal meaning and shared knowledge. Through quantitative content analysis of chat transcripts, it finds that social and teaching presence enhance cognitive presence, facilitating a non-linear progression through the practical inquiry model. Recommendations suggest that chat spaces may foster higher-order thinking in a community of inquiry context.

![For More Information Contact David S. Stein, Ph.D. stein.1@osu.edu Ruth A. Harris [email_address] Lynn A. Trinko [email_address]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/midwest-conference-pwrpt-presentation10-final-show-1232464367087584-1/75/From-Personal-Meaning-to-Shared-Understanding-The-Nature-of-Discussion-in-a-Community-of-Inquiry-25-2048.jpg)