The document discusses advanced concepts in functional programming using Scala, focusing on monads, error handling, and laziness versus strictness. It explains how monadic types like Option, Try, and Either can handle errors and propagate them through computations without breaking the flow. Additionally, it introduces constructs for lazy evaluation and showcases how to create and manipulate streams, futures, promises, and state monads, emphasizing purity and referential transparency.

![for comprehension (review)

Use the OO/FP hybrid style List code

we can do

def test = {

val a = List(1,2)

val b = List(3,4)

for {

t1 <- a

t2 <- b

} yield ((t1,t2))

}

We get

[ (1,3) (1,4) (2,3) (2,4) ]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart2-140918135038-phpapp02/85/Fp-in-scala-part-2-2-320.jpg)

![Error Handling

This can cause ArithmeticException

def mean(xs: Seq[Double]): Double =

xs.sum / xs.length

Explicitly throw it, this is not pure (does not always return)

def mean(xs: Seq[Double]): Double =

if (xs.isEmpty)

throw new ArithmeticException("mean of empty list!")

else xs.sum / xs.length

Have default number instead of throw exception,this is pure as it return Double

all the time. But still bad for using a Double to represent empty List

def mean_1(xs: IndexedSeq[Double], onEmpty: Double): Double =

if (xs.isEmpty) onEmpty

else xs.sum / xs.length

All What else can we do?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart2-140918135038-phpapp02/85/Fp-in-scala-part-2-4-320.jpg)

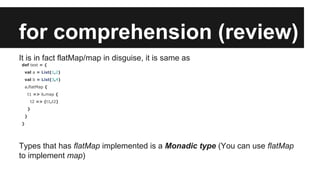

![Option/Try/Either

sealed trait Option[+A]

case object None extends Option[Nothing]

case class Some[+A](get: A) extends Option[A]

def mean_option(xs: Seq[Double]): Option[Double] =

if (xs.isEmpty) None

else Some(xs.sum / xs.length)

sealed trait Try[+T]

case class Failure[+T](exception: Throwable) extends Try[T]

case class Success[+T](value: T) extends Try[T]

def mean_try(xs: Seq[Double]): Try[Double] =

if (xs.isEmpty) Failure(new ArithmeticException("mean of

empty list!"))

else Success(xs.sum / xs.length)

sealed trait Either[+E,+A]

case class Left[+E](get: E) extends Either[E,Nothing]

case class Right[+A](get: A) extends Either[Nothing,A]

def mean_either(xs: Seq[Double]): Either[String, Double] =

if (xs.isEmpty) Left("Why gave me a empty Seq and ask me to

get mean?")

else Right(xs.sum / xs.length)

Now we return a richer type that can represent

correct value and a wrong value, Option represent

wrong value as None (Nothing), Try represent with

wrong value as Failure (Throwable), Either

represent wrong value as some type you specified.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart2-140918135038-phpapp02/85/Fp-in-scala-part-2-5-320.jpg)

: A =

if (cond) onTrue else onFalse

=> A here means lazy evaluate the passed in parameter,

by not evaluating them until they are used.

if2(false, sys.error("fail"), 3)

get 3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart2-140918135038-phpapp02/85/Fp-in-scala-part-2-10-320.jpg)

![Stream (Lazy List)

sealed abstract class Stream[+A]

object Empty extends Stream[Nothing]

sealed abstract class Cons[+A] extends Stream[A]

def empty[A]: Stream[A] = Empty // A "smart constructor" for creating an empty stream of a particular type.

def cons[A](hd: => A, tl: => Stream[A]): Stream[A] = new Cons[A] { // A "smart constructor" for creating a nonempty stream.

lazy val head = hd // The head and tail are implemented by lazy vals.

lazy val tail = tl

}

By carefully using lazy val and => in parameter list, we can

achieve the lazy List: Stream, whose data member will not

be evaluated before get used.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart2-140918135038-phpapp02/85/Fp-in-scala-part-2-12-320.jpg)

(f: S => Option[(A, S)]): Stream[A] =

f(z) match {

case Some((h,s)) => cons(h, unfold(s)(f))

case None => empty

}

unfold is a generic powerful

combinator to generate infinite

Stream.

val fibsViaUnfold: Stream[Int] = cons(0,

unfold((0,1)) { case (f0,f1) => Some((f1,(f1,f0+f1))) })

def test6 = fibsViaUnfold.take(5).toList

get

List(0, 1, 1, 2, 3)

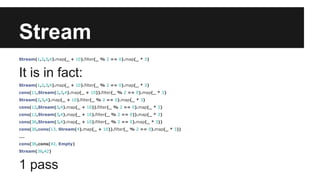

Stream is also a monadic type like

List, and can use for comprehension:

def test = {

val a = Stream(1,2)

val b = Stream(3,4)

for {

t1 <- a

t2 <- b

} yield ((t1,t2))

}

get

Stream((1,3), ?)

? means it is lazy evaluated, you need

to use toList/foreach to get the real

value](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart2-140918135038-phpapp02/85/Fp-in-scala-part-2-14-320.jpg)

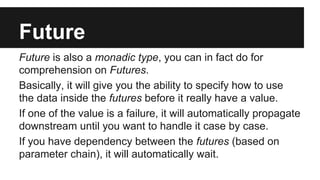

![Future

trait Future[+T]

when complete return a Try[T]

trait Promise[T]

It wraps in a future result of type T which can be a Failure

It is closely related to Promise, Promise is one way to

generate a Future. Promise generate a Future and later

fulfill it.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart2-140918135038-phpapp02/85/Fp-in-scala-part-2-15-320.jpg)

![Future/Promise

val p = promise[Int]

val f = p.future

def producer = {

println("Begin producer")

Thread.sleep(3000)

val r = 100 //produce an Int

p success r

println("end producer")

}

def consumer = {

println("Begin consumer")

f onSuccess {

case r => println("receive product: " + r.toString)

}

println("end consumer")

}

def test2 = {

consumer

producer

}

get result as:

Begin consumer

end consumer

Begin producer

(after 3 secs)

end producer

receive product: 100](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart2-140918135038-phpapp02/85/Fp-in-scala-part-2-16-320.jpg)

![Future

def xFut: Future[Int] = future {

Thread.sleep(10000);

println("x happened");

10

}.flatMap(i => Future.successful(i + 1))

def yFut(a: Int) : Future[Int] = future {

println("y begin")

Thread.sleep(6000);

println("y happened " + a);

20

}

def zFut(a: Int): Future[Int] = future {

println("z begin")

Thread.sleep(5000);

println("z hapenned " + a);

30

}

result is:

(after 10 secs) x happened

(immediately after) y begin

(immediately after) z begin

(after 5 secs) z hapenned 11

(after 1 secs) y happened 11

(after 4 secs)

The end

def test = {

val xf = xFut

val result: Future[(Int, (Int, Int))] =

for {

x <- xf

a <- af(x)

} yield (x, a)

Thread.sleep(20000)

println("nThe end")

}

def af: Int => Future[(Int, Int)] = a =>

{

val yf = yFut(a)

val zf = zFut(a)

for {

y <- yf

z <- zf

} yield ((y,z))

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart2-140918135038-phpapp02/85/Fp-in-scala-part-2-18-320.jpg)

![IO monad

wrap in the IO side effect and

produces description of the IO

effect (without executing), and

then at the end, let some

interpreter do the job based on

the description.

So you have a pure core, and a

non pure shell for you program.

trait IO[+A] {

self =>

def run: A

def map[B](f: A => B): IO[B] =

new IO[B] { def run = f(self.run) }

def flatMap[B](f: A => IO[B]): IO[B] =

new IO[B] { def run = f(self.run).run }

}

object IO {

def unit[A](a: => A): IO[A] = new IO[A] { def run = a }

def flatMap[A,B](fa: IO[A])(f: A => IO[B]) = fa flatMap f

def apply[A](a: => A): IO[A] = unit(a)

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart2-140918135038-phpapp02/85/Fp-in-scala-part-2-20-320.jpg)

![IO monad in action

def ReadLine: IO[String] = IO { readLine }

def PrintLine(msg: String): IO[Unit] = IO { println(msg) }

def fahrenheitToCelsius(f: Double): Double =

(f - 32) * 5.0/9.0

def converter: IO[Unit] = for {

_ <- PrintLine("Enter a temperature in degrees fahrenheit: ")

d <- ReadLine.map(_.toDouble)

_ <- PrintLine(fahrenheitToCelsius(d).toString)

} yield ()

get

IO[Unit] = IO$$anon$2@2a9d61bf

converter.run

This will really run it.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart2-140918135038-phpapp02/85/Fp-in-scala-part-2-21-320.jpg)

![State monad

sealed trait State[S,A] { self =>

def run(s: S): (A,S)

def map[B](f: A => B): State[S,B] = new State[S,B] {

def run(s: S) = {

val (a, s1) = self.run(s)

(f(a), s1)

}

}

def flatMap[B](f: A => State[S,B]): State[S,B] = new

State[S,B] {

def run(s: S) = {

val (a, s1) = self.run(s)

f(a).run(s1)

}

}

}

object State {

def apply[S,A](f: S => (A,S) ) = {

new State[S,A] {

def run(s: S): (A,S) = f(s)

}

}

def unit[S, A](a: A): State[S, A] =

State(s => (a, s))

def get[S]: State[S, S] = State(s => (s, s))

def set[S](s: S): State[S, Unit] = State(_ => ((), s))

def modify[S](f: S => S): State[S, Unit] = for {

s <- get

_ <- set(f(s))

} yield ()

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart2-140918135038-phpapp02/85/Fp-in-scala-part-2-24-320.jpg)

![State monad in action

trait RNG {

def nextInt: (Int, RNG)

}

case class Simple(seed: Long) extends RNG{

def nextInt: (Int, RNG) = {

val newSeed = (seed * 0x5DEECE66DL + 0xBL) & 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFL

val nextRNG = Simple(newSeed)

val n = (newSeed >>> 16).toInt

(n, nextRNG)

}

}

type Rand[A] = State[RNG, A]

val int: Rand[Int] = State(_.nextInt)

generate new random generators:

val posInt = int.map[Int]{ i:Int => if (i < 0) -(i + 1) else i }

def positiveLessThan(n: Int): Rand[Int] = posInt.flatMap {

i => {

val mod = i % n

if (i + (n-1) - mod > 0) State.unit(mod) else positiveLessThan(n)

}}

positiveLessThan(6).run(Simple(5))

produce: 0 (now we can test it)

chain of state transitions: produce 3 result from one initial state

def test4 =

for {

x <- int

y <- int

z <- posInt

} yield ((x , y , z))

test4.run(Simple(1)) produce ((384748,-1151252339,549383846),

Simple(245470556921330))](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart2-140918135038-phpapp02/85/Fp-in-scala-part-2-26-320.jpg)

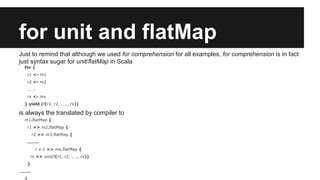

: A = a

// compose function:

// def compose[A,B,C](f: B => C, g: A => B): A => C =

// a => f(g(a))

trait Functor[F[_]] {

def map[A,B](fa: F[A])(f: A => B): F[B]

}

// Functor Law

// identity: map(x)(id) == x

// composition: map(a)(compose(f, g)) == map(map(a,g), f)

trait Monad[F[_]] extends Functor[F] {

def unit[A](a: => A): F[A]

def flatMap[A,B](ma: F[A])(f: A => F[B]): F[B]

override def map[A,B](ma: F[A])(f: A => B): F[B] =

flatMap(ma)(a => unit(f(a)))

}

// Monad Law

// left identity: f(a) == flatmap(unit(a), f)

// right identity: a == flatMap(a, x => unit(x))

// associativity: flatMap(a, x => flatMap(f(x), g)) == flatMap(flatMap(a, f), g)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart2-140918135038-phpapp02/85/Fp-in-scala-part-2-30-320.jpg)

![Higher Kinded Type

[F[ _ ]] is called Higher Kinded Type in Scala, basically a type of types.

Compare to normal [A], this basically says we have a type F that will be used in

code, and F itself is a type that can use F[A], where A is a value type.

Use the value constructor to make a comparison:

proper first-order higher-order

value 10 (x: Int) => x (f(Int => Int)) => f(10)

type String List Monad](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart2-140918135038-phpapp02/85/Fp-in-scala-part-2-31-320.jpg)

: M[A]

def flatMap[A,B](ma: M[A])(f: A => M[B]): M[B]

A bit long explanation here:

Monad seems just like a wrapper, it wraps in a basic type (A here), and put into a context M, generate

a richer type (M[A] here). unit function does this.

We care about the value of type A in context M, but we hate part of the context that is troublesome.

The troublesome part in the context M make us lose the composability for values of type A in

context M (make us not be able to combine functions generate value of type A). So we wrap in the

value and troublesome part together into context M, and now we can combine functions that generate

M[A], just as if the troublesome part is gone. That is what flatMap does.

Using unit and flatMap, we regain the composability for values of type A in context M, which is

kind of what monad brings us, and it specifically useful in pure FP as side effect are the things prevent

clean combination of functions.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fpinscalapart2-140918135038-phpapp02/85/Fp-in-scala-part-2-34-320.jpg)