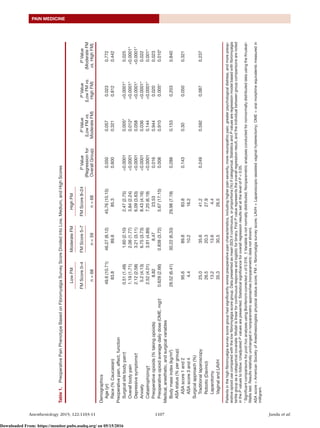

This study examined whether higher scores on a fibromyalgia survey were associated with increased opioid consumption after hysterectomy, while accounting for known risk factors. The study found:

1) Higher scores on the fibromyalgia survey were independently associated with greater postoperative opioid use, with opioid consumption increasing by 7 mg of oral morphine equivalents for every 1-point increase on the 31-point survey scale.

2) In addition to fibromyalgia survey scores, factors like more severe medical comorbidities, greater catastrophizing, laparotomy surgical approach, and preoperative opioid use predicted increased postoperative opioid needs.

3) These results suggest that the fibromyalgia survey may help identify patients at high risk for needing more opioids after surgery, and that