This document provides an overview of the operational environment and organizations of reconnaissance troops. It describes the six dimensions that comprise the operational environment - threat, political, unified action, land combat operations, information, and technology. It then outlines the two types of reconnaissance troops - the Recce Troop of the RSTA squadron and the Brigade Reconnaissance Troop. Their primary missions involve conducting reconnaissance and security operations.

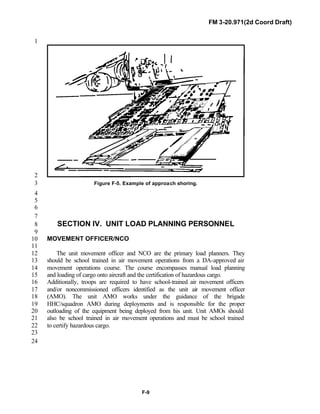

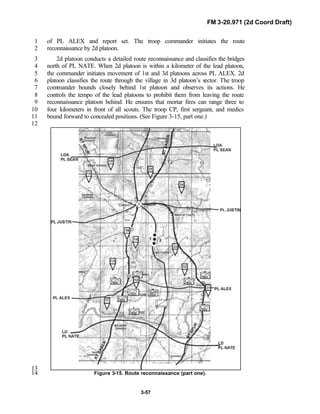

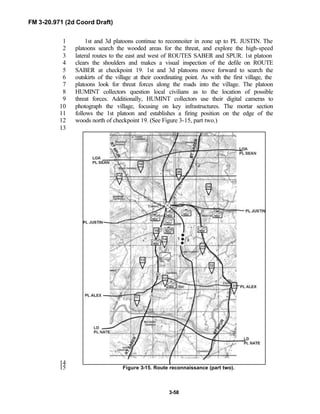

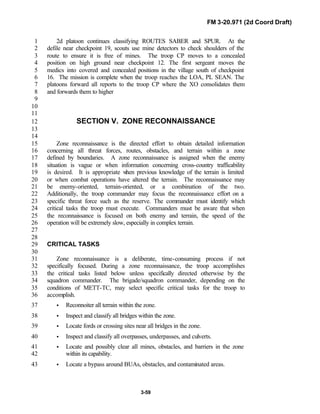

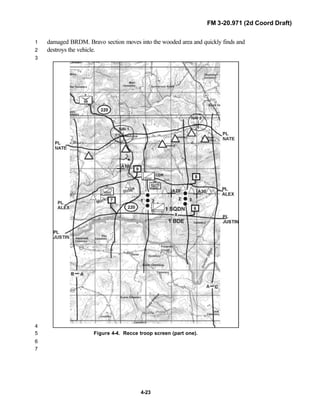

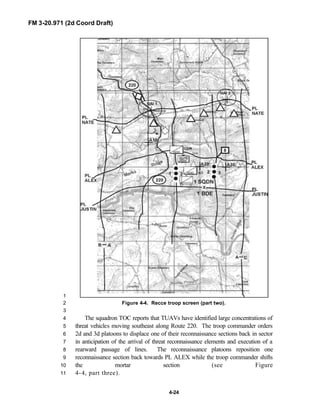

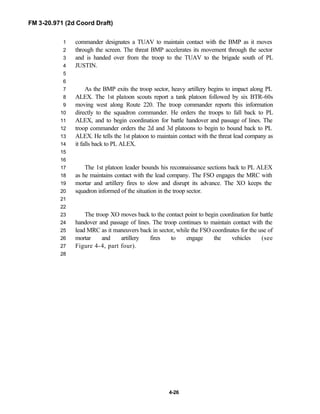

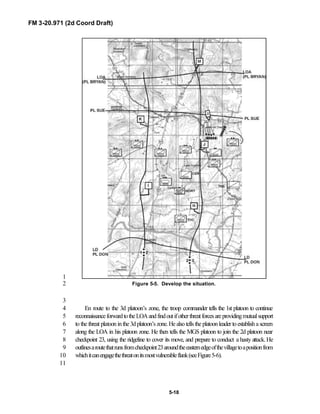

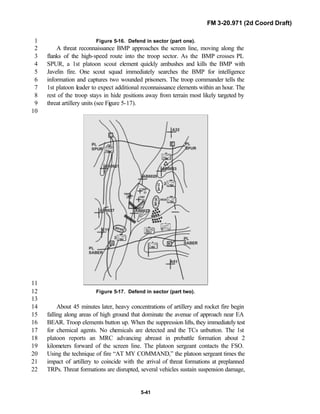

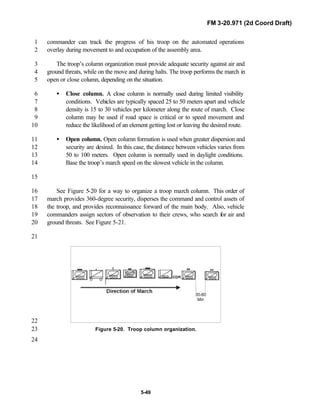

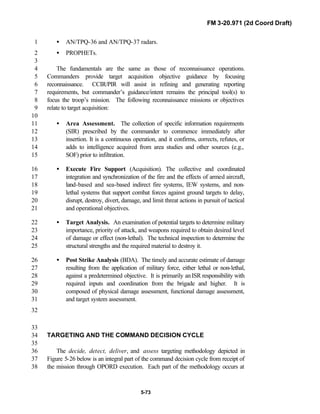

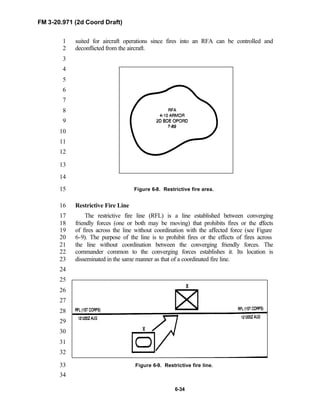

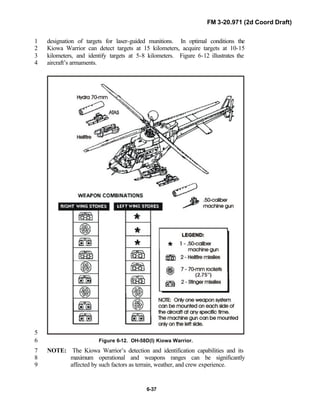

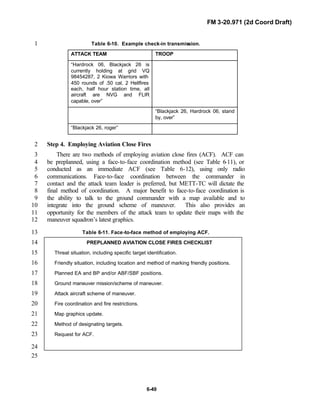

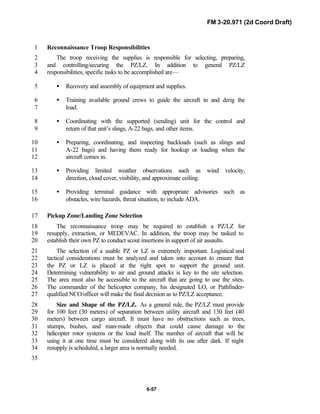

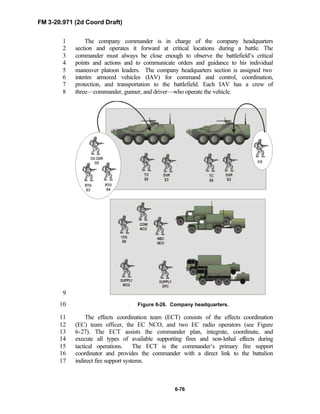

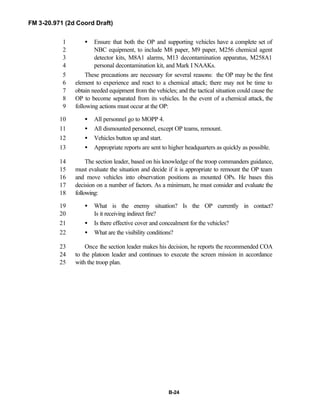

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

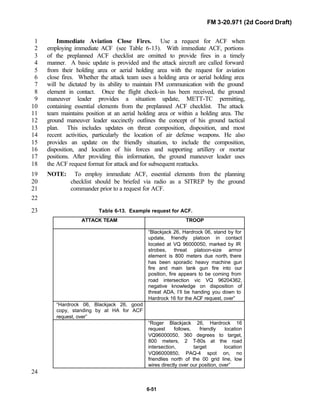

iii

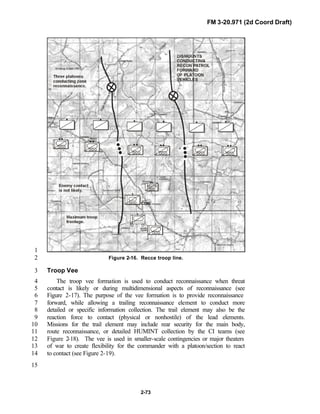

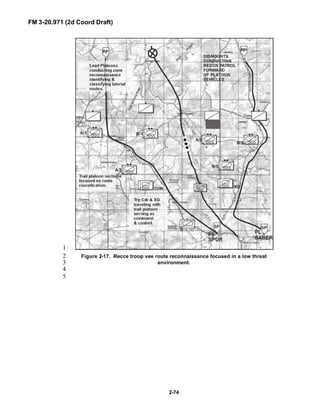

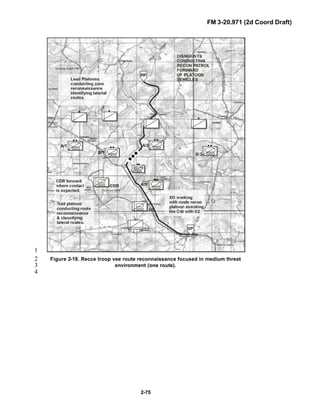

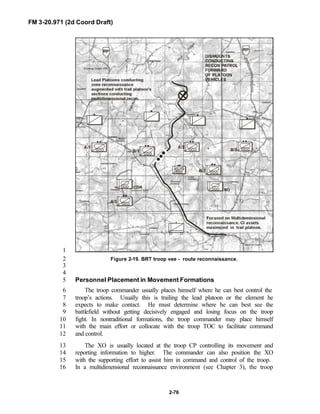

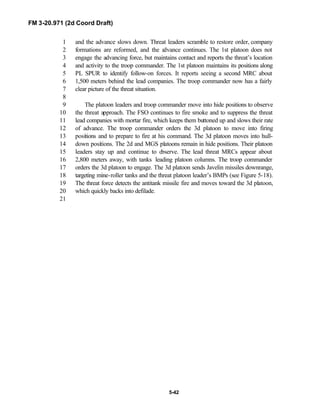

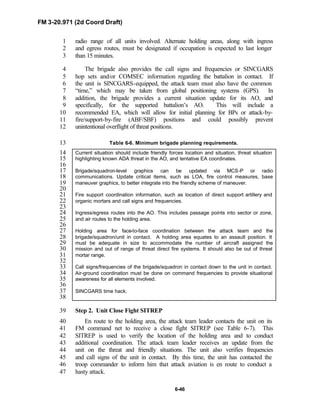

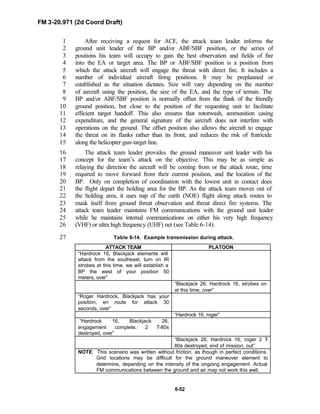

PREFACE1

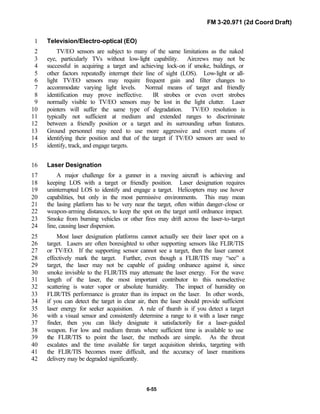

2

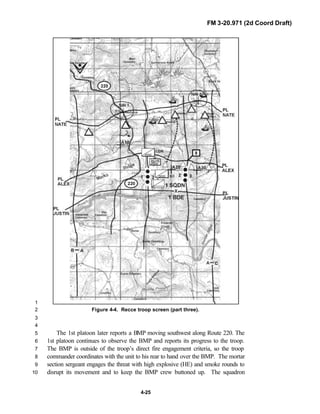

3

FM 3-20.971 describes the tactical employment and operations of4

reconnaissance troops of armored and mechanized infantry brigades (BRTs)5

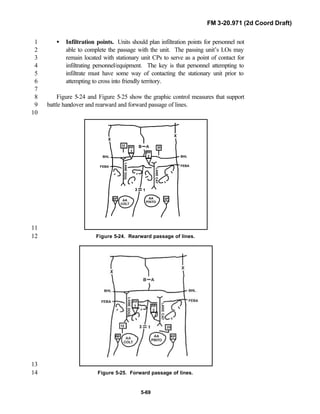

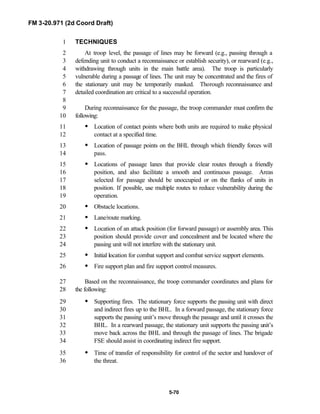

and the recce troops of the Reconnaissance Surveillance and Target6

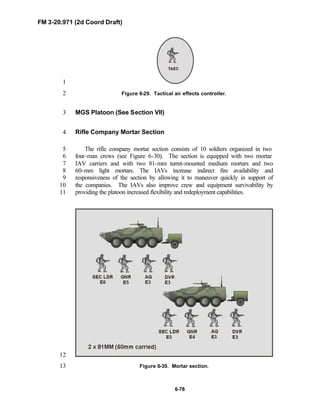

Acquisition (RSTA) squadrons. It specifically addresses operations for7

brigades organized under the Army of Excellence, the Limited Conversion8

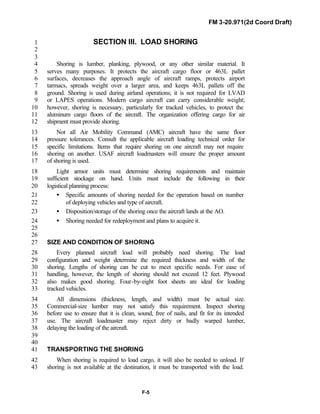

Division force designs, and the Interim Brigade Combat Team (IBCT). FM 3-9

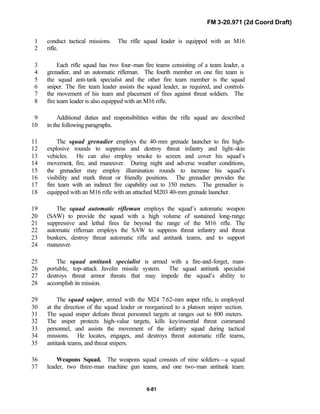

20.971 is the doctrinal foundation that governs the development of equipment,10

training, and structure for both types of reconnaissance troops.11

12

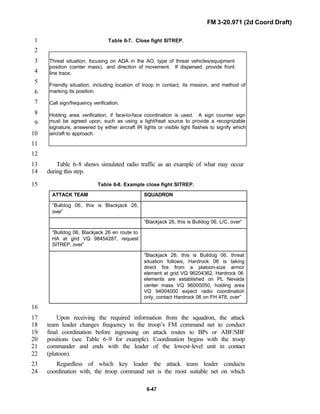

Because not all units are digitally equipped, this manual addresses analog13

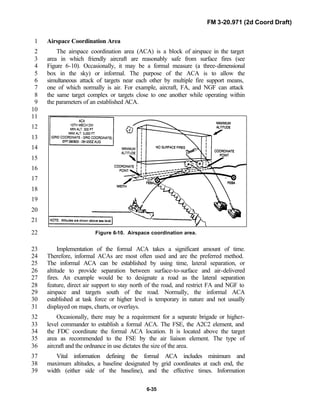

and digital operations, technology applications, and equipment. Tactical14

fundamentals do not change with the fielding of new equipment; however, the15

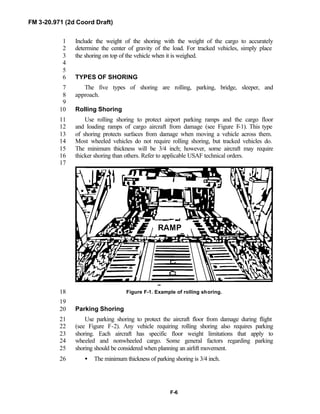

integration of new equipment and organizations may require changes in16

related techniques and procedures. This manual provides guidance in the17

form of combat-tested concepts and ideas modified to exploit emerging Army18

and Joint capabilities.19

20

FM 3-20.971 is written for the recon troop commander and his key leaders21

within the troop. The manual reflects and supports the Army operations22

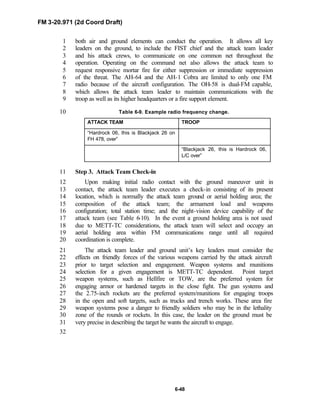

doctrine as stated in FM 3-0. Readers should be familiar with FM 3-91.3 [FM23

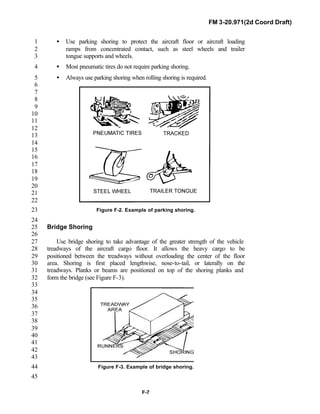

71-3], FM 3-20-97 [FM 17-97], FM 3-100.40 [FM 100-40], FM 3-71 [FM 71-24

100], FM 3-55 [FM 100-55], FM 102 [FM 101-5-1], and FM 3-20.98 [FM 17-25

98]. Examples and graphics are provided to illustrate principles and concepts,26

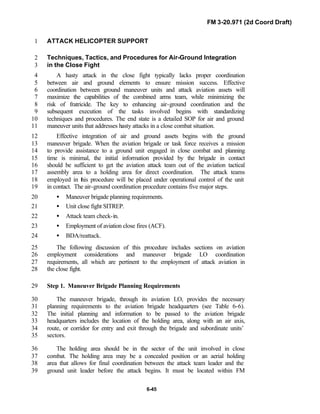

not to serve as prescriptive responses to tactical situations. This publication27

provides units with the doctrinal foundation to train leaders, guide tactical28

planning, and develop standing operating procedures (SOP). The publication29

applies to all reconnaissance troops in the active component (AC) and reserve30

component (NG/RC) force.31

32

Unless otherwise stated, masculine nouns and pronouns do not refer33

exclusively to men.34

35

US Army Armor Center is the proponent for this publication. Submit36

comments and recommended changes and the rational for those changes on37

DA Form 2028 (Recommended Changes to Publications and Blank Forms) to:38

Commander, US Army Armor Center, ATTN: ATZK-TDD-C, Fort Knox, KY39

40121-5000, or e-mail the DA Form 2028 to Chief, Cavalry Branch, from the40

Doctrine Division web site at41

http://147.238.100.101/center/dtdd/doctrine/armordoc.htm. (After accessing42

the web site, select “Organization” from the menu on the left side of the43

screen to reach the Cavalry Branch site.)44

45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-4-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

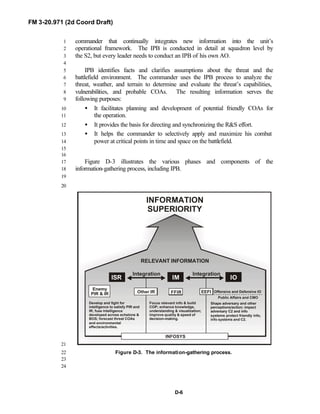

1-13

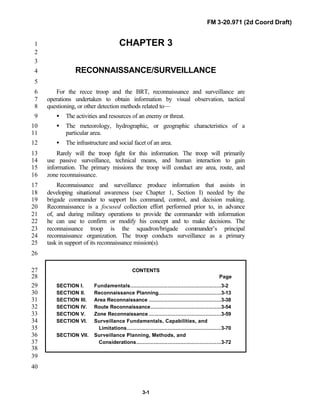

Information superiority is a

significant information advantage

gained by collecting, processing, and

disseminating an uninterrupted flow

of relevant information in support of

military operations while exploiting or

denying a threat or adversary the

ability to do the same.

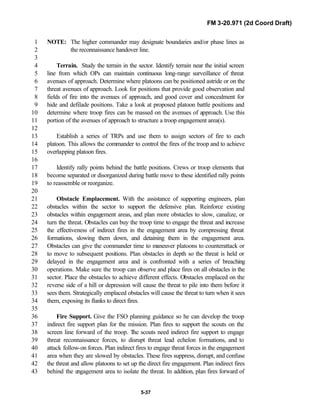

1

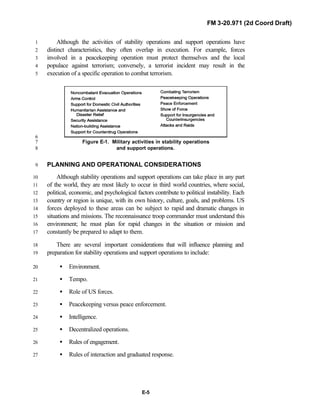

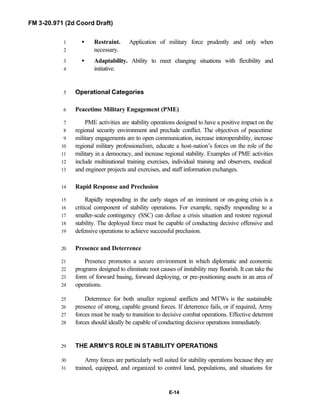

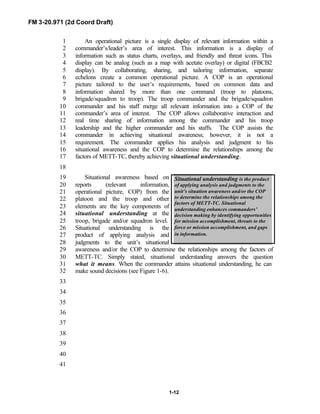

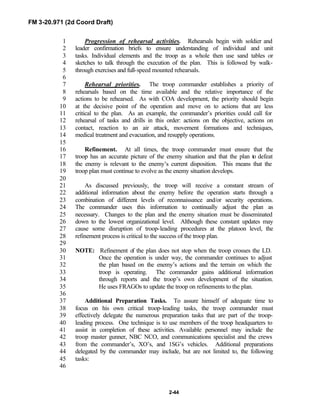

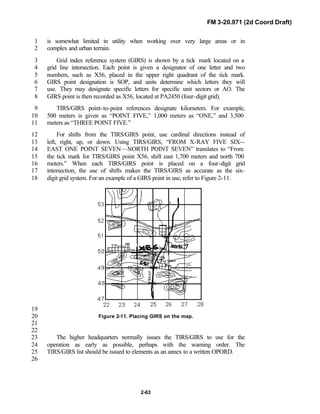

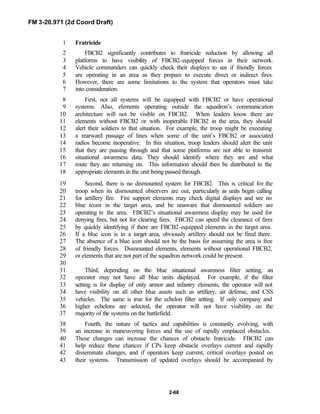

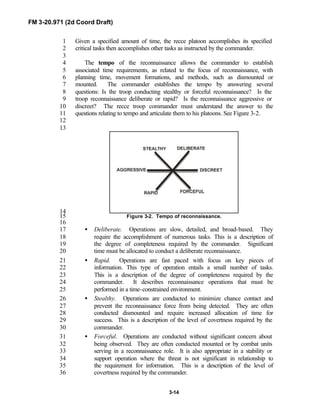

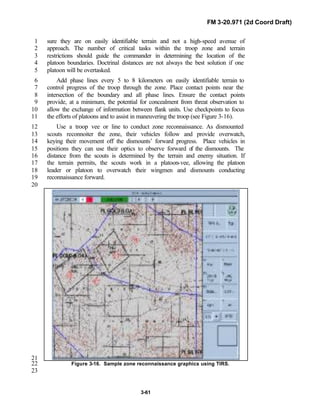

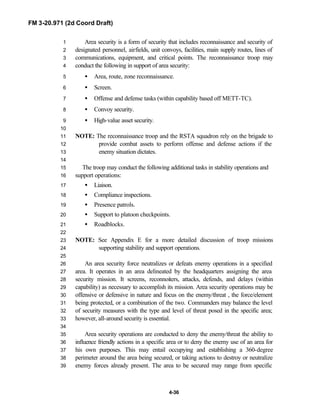

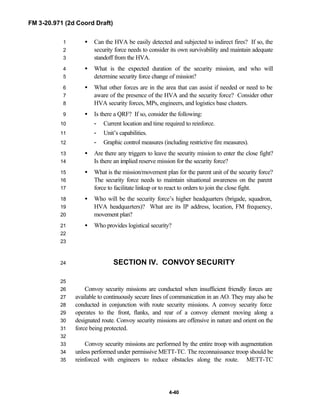

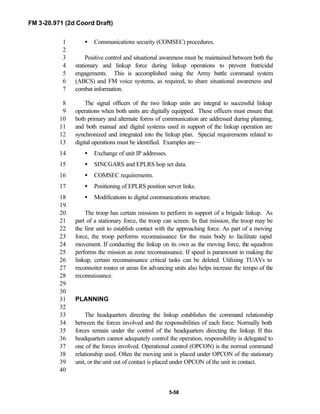

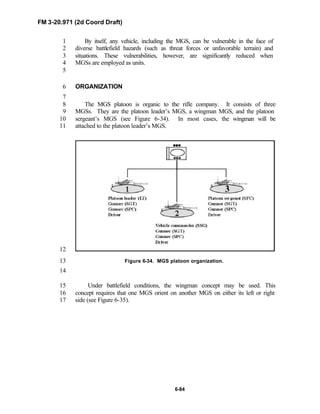

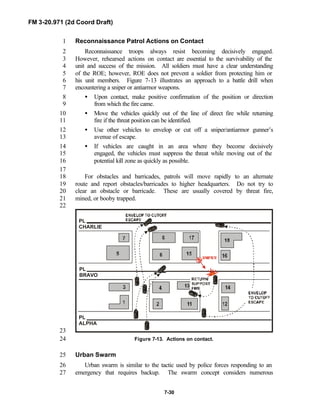

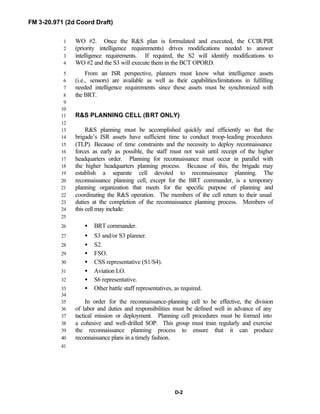

Figure 1-6. Flow of relevant information into2

situational understanding.3

4

Information superiority is the5

operational advantage derived from the6

ability to collect, process, and disseminate7

an uninterrupted flow of information8

while exploiting or denying an adversary’s9

ability to do the same. Commanders10

exploit information superiority to impact11

threat perceptions, attitudes, decisions,12

and actions to accomplish mission objectives. During the course of13

operations, all sides attempt to gain information superiority to secure an14

operational advantage while denying it to adversaries. (NOTE: See FM 3-015

[FM 100-5] for more information on information superiority.)16

17

Visualizing the Battlefield18

The greatest challenge leaders face during operations is seeing, or more19

accurately, “visualizing” the battlefield in both real time and in the future.20

Normally their physical view is limited to brief segments of the battlefield.21

They must develop an art of visualizing what is occurring or might occur22

within their area of interest. For some, this comes almost naturally. For most,23

however, it requires a great deal of experience to adequately visualize the24

complexities of the battlefield. Enhanced analog and digital communications25

(FBCB2), computers, and command/control (C4) systems in the troop portray26

key relevant threat information so that commanders and staffs can better27

visualize the battlefield and be situationally aware. Not only will these28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-17-320.jpg)

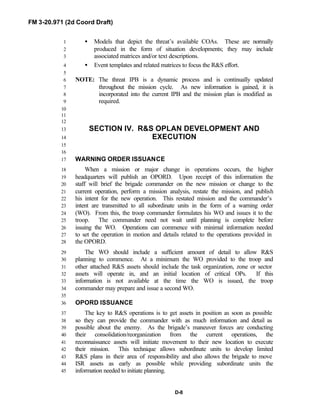

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

2-6

• To preserve the reconnaissance capability of the platoon, and inform1

the commander and XO of the tactical situation via FM and digitized2

contact and spot reports.3

• To lead an integrated scout/STRIKER platoon in executing both fire4

support and R&S missions.5

Reconnaissance Platoon Sergeant6

The platoon sergeant is the senior NCO in the platoon. He leads elements7

of the platoon as directed by the platoon leader and assumes command of the8

platoon in the platoon leader’s absence. He assists the platoon leader in9

maintaining discipline and exercising control. He supervises platoon CSS, to10

include supply requirements and equipment maintenance, and monitors the11

platoon’s logistics status and submits FBCB2 LOGSTAT reports.12

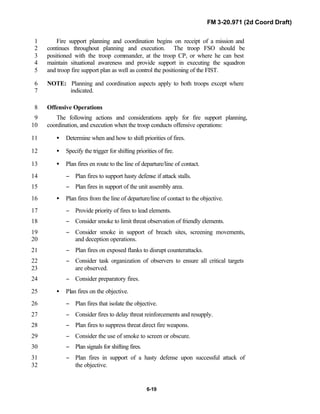

Fire Support Team13

The fire support team (FIST) is the critical link with the supporting14

artillery and is responsible for coordinating indirect fires (mortar, field15

artillery [FA], close air support [CAS]) for the troop. The team processes16

calls for fire from the platoons and allocates the appropriate indirect-fire17

system based on the commander’s guidance for fire support. The FIST can18

also assist the brigade/squadron with the employment of joint fires.19

NOTE: In the brigade reconnaissance troop (BRT), the STRIKER platoon20

leader may fill the role of the FIST.21

The FIST operates on three radio nets:22

• Troop command.23

• Troop fire direction.24

• Squadron fire support element digital/voice.25

26

The FIST monitors at least one of the following nets:27

• Squadron command.28

• Squadron operations and intelligence (OI).29

• Firing battery (supporting artillery headquarters in the heavy and light30

division).31

32

The fire support team vehicle also may serve as the alternate troop CP.33

The fire support officer has ready access to the higher-level situation and the34

radio systems to replicate the troop CP if it becomes damaged or destroyed.35

36

Command guidance to the FIST should include the following:37

• Purpose of indirect fires. How does the commander intend to use FA38

and mortar fires to support his maneuver?39](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-38-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

2-54

Automated Nuclear, Biological and Chemical Information System1

(ANBACIS) (Chemical [NBC] Functions)2

This software is used to report NBC strikes/warnings and to predict the3

contamination areas associated with such strikes. The software is loaded on4

select MCS computers.5

6

Digital Topographic Support System (Engineer Functions)7

This system is used by the division engineer to create topographic and8

terrain analysis products that can easily be accessed via the MCS.9

CHATS (HUMINT Collector Functions)10

This system is a portable or vehicle mounted computer system used by the11

HUMINT intelligence collectors assigned throughout the squadron to report12

HUMINT operations and maintain an operational database.13

Army Battle Command System Communications Links14

While each component of the ABCS is a powerful C2 tools individually,15

they reach their full potential when linked by a local area network (LAN), a16

wide area network (WAN), or the TI.17

Local Area Network18

A LAN network is a data communications network that interconnects19

digital devices and other peripherals. Individual systems are linked and20

distributed over a localized area to allow communication between computers21

and sharing resources. Two or more computers linked by software and22

connected by cable are considered a LAN. A LAN includes—23

• Digital devices (computers, scanners, printers, and other peripherals).24

• A communications medium that exchanges data from one device to25

another.26

• Network adapters that provide devices with an interface to the27

communications medium.28

Digital systems within a CP are normally connected on a LAN. However,29

routers on the LAN allow addressees to change as needed for jump and/or30

split operations. A tactical LAN is configured to interconnect various main CP31

shelters. Staff leaders must ensure the LAN cables are properly connected to32

their shelter/system and to the previous and next shelter/system. The S6 is the33

LAN manager for the squadron and has approval authority over all systems34

connected to the LAN. The LAN manager is responsible for physically35

establishing, connecting, and maintaining the operation and for36

troubleshooting the LAN. He is also responsible for ensuring the LAN is37

connected to the WAN. See FM 6-24.7 [FM 24-7] for additional information.38](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-86-320.jpg)

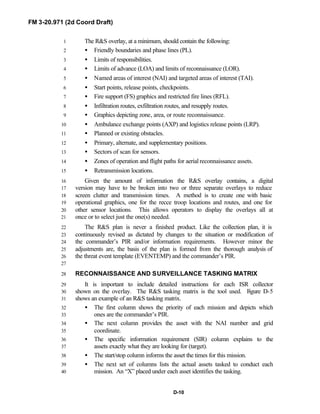

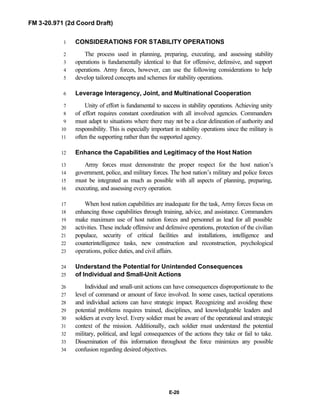

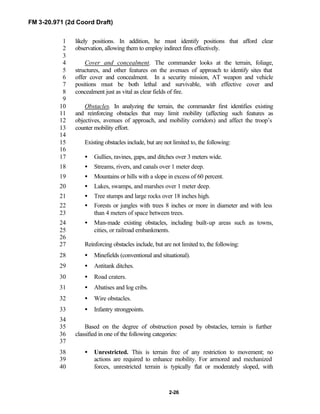

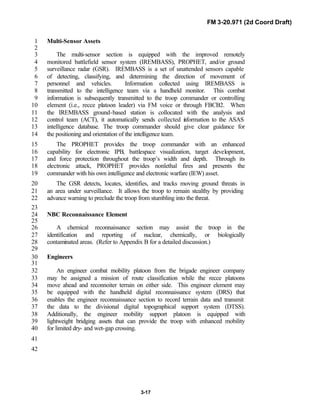

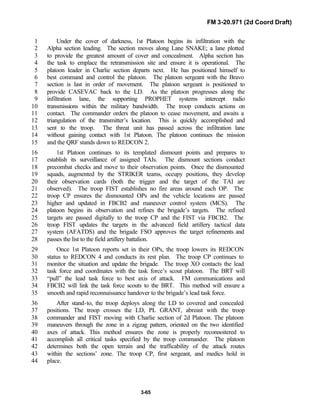

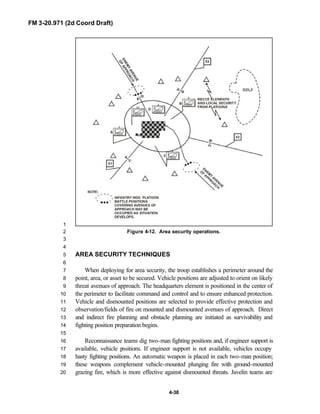

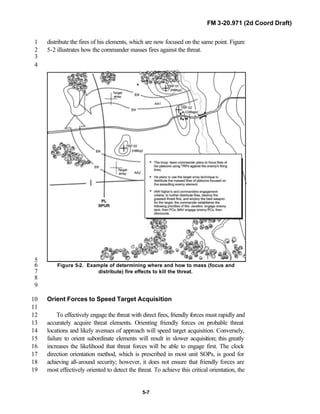

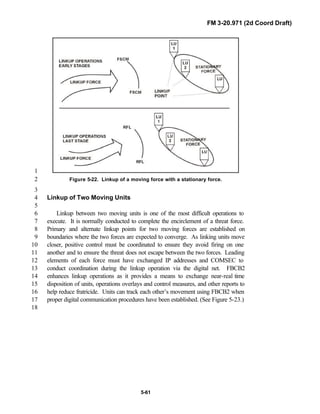

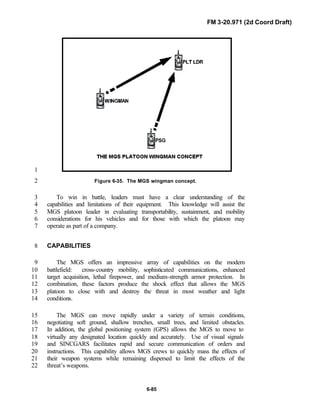

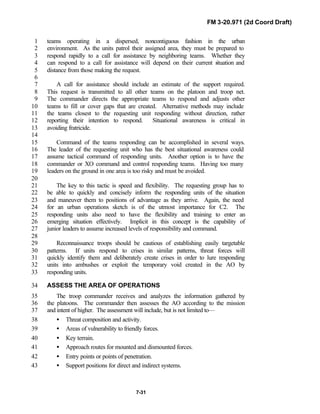

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

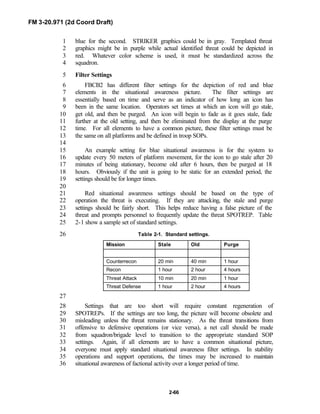

2-56

1

Figure 2-10. Lower tactical internet.2

3

4

Upper Tactical Internet. The upper TI (or WIN-T [Warfighter5

Information Network-Terrestrial]) provides SA and C2 dissemination between6

brigade and squadron CPs and echelons above brigade CPs.7

8

9

Security10

The information architecture on the battlefield contributes significantly to11

the warfighting capabilities of units on the battlefield. The digitized12

battlefield brings a new threat—computer network attack (CNA). CNA13

includes operations the threat undertakes to disrupt, deny, degrade, or destroy14

information resident in computers and networks. To protect against CNA,15

security architecture is being developed which will involve security16

technologies, such as firewalls, intrusion detection systems, in-line network17

encryptors, and host security. The digital security requirements are defined in18

AR 380-19 and the PEO Command, Control and Communications Systems19

(PEO C3S) Security Policy.20

21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-88-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

3-5

more detailed, comprehensive reconnaissance and surveillance mission.1

Understanding the multiple dimensions of the focus of reconnaissance is2

paramount in the troop’s understanding of the operational environment.3

Reconnaissance focus should be centered on reducing the unknowns of the4

environment based on the intelligence preparation of the battlefield (IPB)5

process and integrally connected to and fulfilling the commander’s CCIR. The6

focus of reconnaissance is characterized in these broader terms: enemy/threat,7

social/human (demographics), infrastructure, and terrain.8

9

Enemy/Threat10

11

The troop no longer faces a single, monolithic, or well-defined threat.12

During the cold war, planning centered on confronting numerically superior13

armored opposing forces in Europe, the Far East, or Southwest Asia. Today’s14

reconnaissance units must be able to conduct operations across the range of15

military operations (major theater of war [MTW], smaller-scale contingencies16

[SSC], and stability operations and support operations) against threats ranging17

in size from major regional powers to asymmetric threats. These may include18

conventional threat forces, insurgents, paramilitary forces, guerrillas, criminal19

groups, and certain civilian groups and individuals. Because of the diversity of20

the threat, the IPB process becomes even more important at the brigade,21

squadron, and troop levels. No longer will the threat always fit into a neat22

time-distance scenario. Potential adversaries may use a variety of doctrine,23

tactics, and equipment. It is extremely important to quickly identify who the24

enemy/threat is in an operational area. This will continually be the major25

focus of reconnaissance for the troop. However, reconnaissance focus may be26

the identification of the unknown threat as well. That is why the27

understanding of the society and infrastructures of an area are also an28

important focus for reconnaissance.29

30

Society (Social/Human Demographics)31

32

The focus of reconnaissance may be the society of a given area. Gaining33

an awareness of how the society impacts military operations and how military34

operations impact the local society may be critical to the commander in order35

for him and his stuff to make decisions.36

37

The center of gravity during operations may be the civilian inhabitants38

themselves. To gain and/or retain the support of the population, commanders39

must first understand the complex nature and character of the society. Second,40

they must understand and accept that every military action (or inaction) may41

influence, positively or negatively, the relationship between the urban42

population and Army forces, and by extension, mission success. Without the43

support of the society or understanding its needs, the society may become a44

threat to the brigade/military operations. With this awareness, commanders45

can plan operations, implement programs, and/or take immediate action to46](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-114-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

3-7

- Local police chief.1

- Local political leaders.2

- Local military commanders.3

- Local religious leaders.4

• Nongovernmental organization.5

• Economy.6

• Media.7

- Organizations.8

- Reporters.9

- Publications.10

- Broadcasts.11

Infrastructure12

The infrastructures are those systems that support the inhabitants and their13

economy and government. Destroying, controlling, or protecting vital parts of14

the infrastructure can isolate the threat from potential sources of support.15

Because these systems are inextricably linked, destroying or disrupting any16

portion of the urban infrastructure can have a cascading effect (either17

intentional or unintentional) on the other elements of the infrastructure.18

To successfully operate in an area, the troop must understand the local19

infrastructure. The troop must understand it physically in terms of utilities,20

transportation, and food availability as well as the many other products that21

make a community run. The troop must understand the infrastructure22

financially. What is the monetary base of the different communities, the23

income demographics, and the black market trade? Additionally, who can24

provide the friendly force with CSS needs? The troop must also understand25

the local community, political, and governmental structure. This includes26

religious, military, and paramilitary, such as local security and police forces27

that work independently from one another. The troop must develop a general28

understanding of these organizations—how they fit into the community at29

large and how they relate to one another. A reconnaissance mission focused30

on infrastructure might look at these dimensions—31

• Communications. (Wireless, telegraphs, radios, television, computers,32

newspapers, magazines, etc.)33

• Transportation and distribution. (Highways and railways [to include34

bridges, tunnels, ferries, and fords]; cableways and tramways; ports,35

harbors, and inland waterways; airports, seaplane stations, and36

heliports; mass transit; and the trucking companies and delivery37

services that facilitate the movement of supplies, equipment, and38

people.)39

• Energy. (System that provides the power to run the urban area and40

consists of the industries that produce, store, and distribute electricity,41](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-116-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

3-8

coal, oil, and natural gas. This area also encompasses alternate energy1

sources such as nuclear, solar, hydroelectric, and geothermal.)2

• Commerce. (Area includes business and financial centers [stores,3

shops, restaurants, marketplaces, banks, trading centers, and business4

offices] and outlying industrial/agricultural features [strip malls, farms,5

food storage centers, and mills] as well as environmentally sensitive6

areas [mineral extraction areas and chemical/biological facilities].)7

• Human services. (Includes hospitals, water supply systems, waste and8

hazardous material storage and processing, emergency services9

[police, fire, rescue, and emergency medical services], and10

governmental services [embassies, diplomatic organizations,11

management of vital records, welfare systems, and the judicial12

system]. The loss of any of these often has an immediate,13

destabilizing, and life-threatening impact on the inhabitants.)14

Terrain15

16

The best terrain analysis is based on a focused reconnaissance of the area17

of operation. Identifying the gaps in knowledge of the terrain that a map18

analysis cannot satisfy is the first step in terrain-focused reconnaissance. The19

troop must see the terrain as it pertains to friendly forces as well as threat20

military operations. Terrain reconnaissance includes the effect of weather on21

the military aspects of the terrain. Terrain-focused reconnaissance evaluates22

the military aspects of the terrain (OCOKA) and provides valuable23

information back to the commander to support his decisions. The side that can24

best understand and exploit the effects of terrain has the best chance of25

success.26

27

To date, cavalry and reconnaissance forces have not focused on urban28

terrain. In fact, doctrine has supported and focused on the identification of29

bypasses around urban terrain. Because of the nature of asymmetric warfare,30

threat elements will further exploit terrain to try and gain an advantage over31

US forces. In the future the troop must become more familiar with the aspects32

of complex and urban terrain. The troop must also see terrain not only in its33

traditional role but also as it might apply in a stability, support, and SSC34

environment. In a stability, support, or SSC environment, key terrain may be35

a religious or cultural monument, or an historic geographical boundary or36

town.37

38

Urban areas include some of the world's most difficult terrain in which to39

conduct military operations. Unlike deserts, forests, and jungles, which40

confront the commander with a limited variety of uniform, recurring terrain41

features, urban operations are conducted within an ever-changing mix of42

natural and manmade features. Urban areas vary immensely depending on43

their history, the cultures of their inhabitants, their economic development, the44

local climate, available building materials, and many other factors. This45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-117-320.jpg)

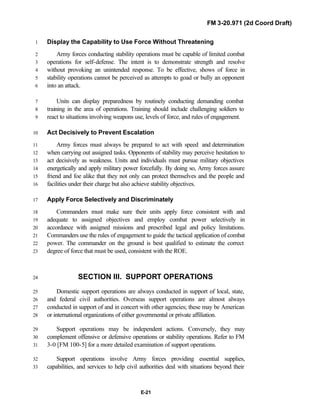

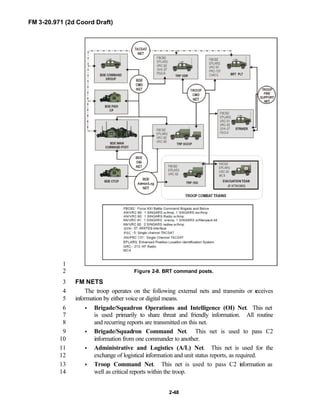

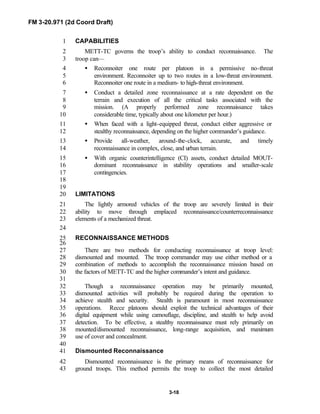

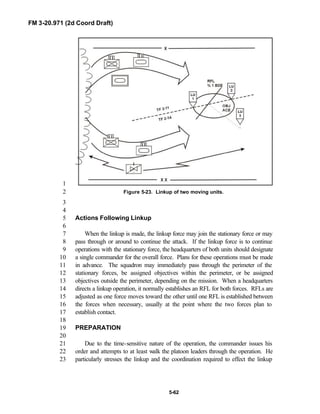

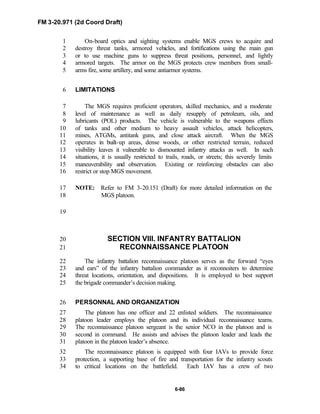

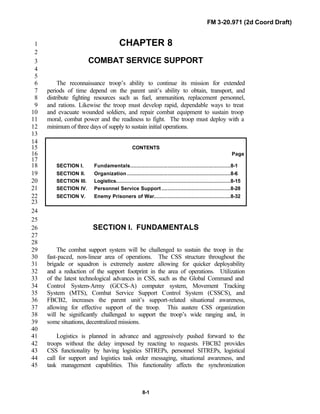

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

3-9

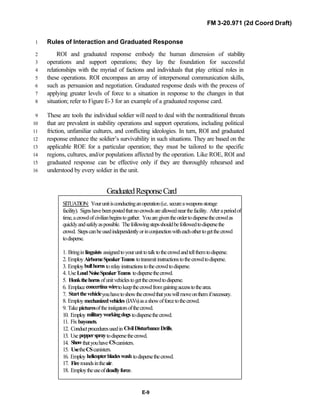

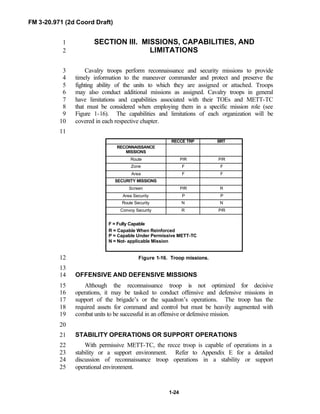

The reconnaissance objective must be

focused at a minimum on:

• Enemy/threat.

• Society.

• Infrastructure.

• And/or Terrain feature.

• Control measure.

The troop and higher headquarter must

endeavor to link the reconnaissance

object and the focus of reconnaissance

to:

• Commander’s critical

information requirements.

• And/or filling voids in the IPB.

• And/or supporting targeting.

variety exists not only among different urban areas but also within any1

particular area. Urban areas present an extraordinary blend of horizontal,2

vertical, interior, exterior, and subterranean forms superimposed upon the3

landscape's natural relief, drainage, and vegetation. The troop must become4

familiar with conducting terrain reconnaissance and evaluating the military5

aspects of urban terrain (OCOKA) as much as forest, desert, and jungle6

terrain. Reconnaissance leaders must become familiar with urban IPB found7

in FM 2-01.3 [FM 34-130], Intelligence Preparation of the Battlefield, and in8

FM 3-06 [FM 90-10], Urban Operations.9

10

FUNDAMENTALS OF RECONNAISSANCE11

Successful reconnaissance operations are planned and performed with the12

following six fundamentals in mind:13

• Orient on the reconnaissance objective.14

• Maximize reconnaissance assets.15

• Gain and maintain contact.16

• Develop the situation.17

• Report all information rapidly and accurately.18

• Maintain the ability to maneuver freely.19

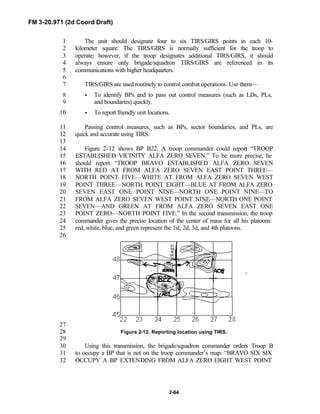

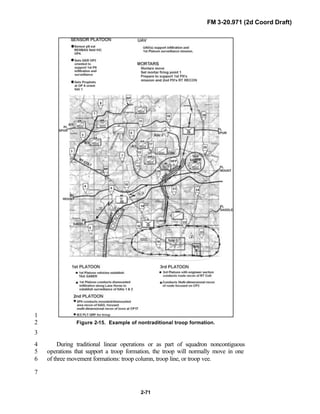

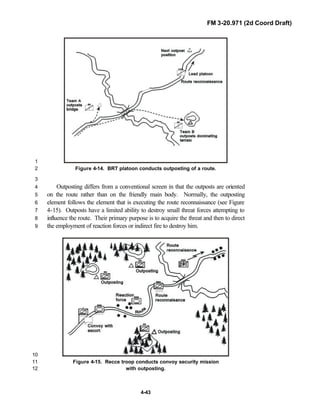

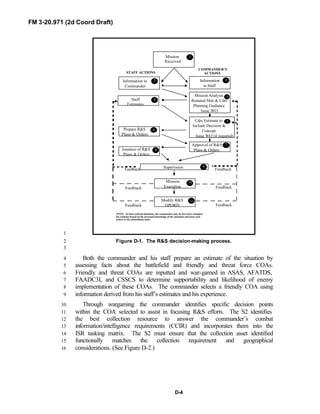

Orient on the Reconnaissance Objective20

The commander focuses the22

efforts of the unit with a24

reconnaissance objective. This26

objective may be a terrain feature,28

control measure, enemy/threat,30

society, and or the infrastructure32

within an area of operation. During34

the IPB process, the S2 will identify36

additional intelligence requirements38

related to the enemy/threat, society,40

infrastructure and terrain. These42

intelligence requirements combined44

with the commander’s critical46

information requirements48

(CCIR)/priority intelligence50

requirements (PIR) are used as tools52

to direct the reconnaissance efforts54

of the troop. This is where the focus56

of reconnaissance is addressed in order to fill in the gaps of information and57

assist in answering the CCIR. Additionally the troop may orient its58

reconnaissance to support targeting for the squadron/brigade. This is linked to59](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-118-320.jpg)

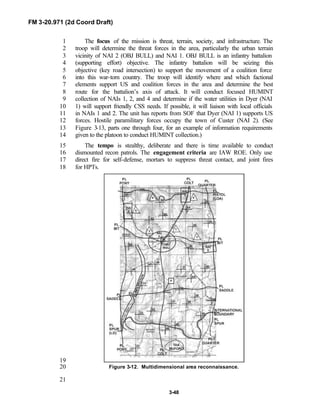

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

3-10

higher CCIR or may just support the targeting process. METT-TC, especially1

time, will influence which critical reconnaissance tasks can be executed2

during the conduct of the mission. Reconnaissance efforts may be focused on3

all multidimensional aspects (enemy/threat, society [human demographics],4

terrain, or the infrastructure) of an area. If reconnaissance efforts are oriented5

mainly on a threat force, the commander must specify the terrain and6

maneuverability data for the troop to gather as well as social and infrastructure7

aspects. In a stability or support operations environment, several things might8

reflect the multidimensional reconnaissance objective. In Bosnia, the9

reconnaissance objective was complying with the Dayton Peace Accord, as10

indicated by compliance with inspectors at weapons storage site facilities, the11

disbanding of illegal factional checkpoints, or the absence of police activity in12

the zone of separation.13

14

Maximize Reconnaissance Assets15

Scouts are the “eyes and ears” of the commander. With their digitized16

capabilities, scouts can provide the early warning the brigade commander17

needs to maneuver and apply his combat power as required at points of his18

choosing. Previous reconnaissance doctrine focused on maximum19

reconnaissance forward, which may still be appropriate in many situations;20

but with the increasing likelihood of noncontiguous operations,21

reconnaissance and security operations may be oriented in multiple directions.22

The troop must integrate a wide range of sensors, to include TUAVs and23

ground sensors, to ensure maximum effectiveness and survivability of ground24

scouts (see Figure 3-1). Other assets to assist the troop gain better situational25

awareness include JSTARS/U2 (imagery) and SOF intelligence operations,26

which are fed through the brigade/squadron’s Trojan system to the troop via27

reports on FBCB2. Maximizing reconnaissance is applying the right28

reconnaissance asset to the reconnaissance objective and providing29

redundancy when necessary as well as the ability to maintain contact30

throughout the depth of an OA. In most cases, the entire troop will be required31

to operate along a traditional linear front, but planning must consider the32

troop’s ability to conduct sustained operations in depth. Operating with two33

platoons oriented forward and one trailing platoon oriented rearward may be34

appropriate in some situations. In stability operations, an example would be35

maximum scout and HUMINT assets among the local populace to gather36

information.37

38](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-119-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

3-20

TACTICAL EMPLOYMENT1

Infiltration2

Infiltration is a form of maneuver that entails movement by small groups3

or individuals at extended or irregular intervals through or into an area4

occupied by an enemy or a friendly force in which contact with the enemy is5

avoided. The troop infiltrates through the area of operations to orient on the6

reconnaissance objective without having to engage the enemy or fight through7

prepared defenses. This form of maneuver is slow and often accomplished8

under reduced visibility conditions. Aerial reconnaissance provides additional9

security for the troop by locating enemy positions and identifying routes on10

which to vector ground elements to avoid enemy contact.11

If contact is necessary to force a gap in enemy defenses, the troop must be12

augmented by infantry forces, MGS, or AT offensive assets to force the13

opening in the threat’s security zone to allow the troop to infiltrate. Another14

technique is for a maneuver team to conduct a probe of threat positions and15

allow the troop to maneuver through the gap that is created. Still another16

technique is to have TUAVs, layered with SIGINT, GSR, and IREMBASS to17

locate openings through threat positions and assist the troop in infiltrating.18

Prior to infiltration, the troop commander will select individual zones or19

routes for the platoons. He will also specify actions on contact. Although the20

intent of the troop scouts is to avoid threat direct fire contact, they must know21

what actions to take upon being engaged. The troop commander establishes22

engagement criteria and issues them in his OPORD. If detected, an23

infiltration element should return fire, break contact, and report (IAW troop24

order, actions on contact, and SOPs). The troop commander will decide25

whether that element should continue the mission or return to friendly lines.26

NOTE: Refer to FM 3-20.98 [FM 17-98] for more detailed discussion of27

infiltration.28

29

Planning30

Infiltration is one of the most difficult missions the lightly armed scouts of31

the troop can accomplish. To maximize the success of the infiltration and32

enhance survivability, scouts need a detailed knowledge of the terrain and up-33

to-date information about the threat. A detailed terrain analysis can be34

conducted with the S2, using the capabilities of ASAS, DTSS, and FBCB2.35

The analysis and control team (ACT) and ASAS data bases can provide36

details related to threat locations and dispositions during infiltration planning,37

and TUAV reconnaissance flights can support both planning and execution.38

The squadron S2 and reconnaissance troop commander will review terrain39

analysis and threat data to locate threat positions and gaps in threat lines. This40

analysis also determines if the commander will move his elements on single or41

multiple infiltration lanes or zone. The overriding factor in determining42](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-129-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

3-22

operation. Recovery, resupply, and MEDEVAC support are critical planning1

aspects for aerial insertions. Deception inserts should be made en route to and2

when returning from the insertion. (See FM 3-97.4 [FM 90-4],3

FM 3-20.98 [FM 17-98], and Chapter 6, Section III, for more information4

related to aerial insertions.)5

Dismounted Infiltration. The troop commander may direct scouts to6

conduct dismounted infiltration when—7

• Time is available.8

• Stealth is required.9

• Enemy contact is expected or has been achieved through visual means.10

• Scout vehicles cannot move through an area because of terrain or11

enemy.12

• Security is the primary concern.13

Mounted Infiltration. The troop commander directs scouts to conduct14

mounted infiltration when—15

• Time is limited.16

• Enemy locations are known.17

• Distances require mounted movement.18

Though an infiltration may be primarily mounted, dismounted activities19

may be required during the operation to achieve stealth and security.20

Employment by Echelon. This technique lends itself to the flexibility21

required by a reconnaissance organization. The troop can move subordinates22

mounted and dismounted, enter the zone at different times and locations, and23

conduct different reconnaissance missions. An example of employment by24

echelon is described below.25

The brigade has a requirement to conduct surveillance of critical NAIs 3626

hours prior to the LD time. The employment of the BRT would create a27

reconnaissance gap. To solve this dilemma, the BRT commander tasks one28

platoon to infiltrate and establish surveillance of the brigade NAIs, while the29

balance of his troop prepares to conduct a zone reconnaissance forward of the30

brigade (prior to its LD).31

Checkpoints32

Checkpoints (or TIRS) should be chosen for all infiltrations/exfiltrations33

to control movement and provide command and control flexibility.34

Checkpoints can be used as a rallying point if a scout element should become35

misoriented, or the threat forces the scout element off the infiltration route or36

OP. These checkpoints should be entered on the FBCB2 systems.37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-131-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

3-29

higher unit to maintain tempo and momentum. In terms of slowing the tempo1

of an operation, however, the loss of a platoon or team is normally much more2

costly than the additional time required to allow the subordinate element to3

properly develop the situation.4

5

Steps for Actions on Contact6

The troop should execute actions on contact using a logical, well-7

organized process of decision making. There are two types of contact the unit8

can expect and prepare for—known and chance. Known contact entails9

information and intelligence on known locations or positions of threat forces.10

Known contact actions entail these seven steps:11

• Make contact through sensors and other ISR assets.12

• Develop the situation out of contact (evaluate the situation [update the13

IPB process]).14

• Maneuver the force out of contact (choose how, with what, and where15

to make contact).16

• Make contact on your own terms (deploy and report).17

• Reevaluate and develop the situation.18

• Choose and/or recommend a COA.19

• Execute the selected COA.20

When there is no intelligence about the threat’s location, chance contact21

may be made. Chance contact actions consist of the same last four steps in22

known contact actions.23

• Deploy and report.24

• Reevaluate and develop the situation.25

• Choose and/or recommend a COA.26

• Execute the selected COA.27

28

The seven- (or four) step process is not intended to generate a rigid,29

lockstep response to the threat. Rather, the goal is to provide an orderly30

framework that enables the unit and its subordinates to survive the initial31

contact, and then apply sound decision making and timely actions to complete32

the operation. Ideally, the unit will acquire the threat (visual contact) before33

being sighted by the threat/enemy; then it can continue with visual contact or34

initiate indirect contact or physical contact on its own terms by executing the35

designated COA. It is also essential for the troop commander to understand36

the higher commander’s intent of the reconnaissance to recommend COAs for37

the brigade/squadron to react to the threat contact.38](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-138-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

4-4

ensure contact is maintained, unless otherwise directed. Ground sensors may1

identify threat movement and TUAVs and/or scouts can maintain contact. The2

reconnaissance troop may use a security drill to maintain threat contact throughout3

the depth of its assigned sector, or it may use other attached assets (i.e., TUAV or4

aerial scouts) to pass the contact back to the brigade or squadron.5

CAPABILITIES6

Capabilities of the RSTA recce troop include—7

• Screen up to a nine-kilometer-wide sector.8

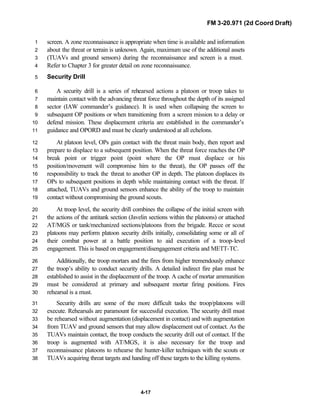

• Maintain continuous surveillance of up to six avenues of approach (through9

six OPs).10

• Can establish up to 12 short-duration and six long-duration OPs.11

12

Capabilities of the BRT include—13

• Screen up to a ten-kilometer-wide sector.14

• Maintain continuous surveillance of up to six avenues of approach (through15

six OPs/NAIs [named areas of interest]).16

• Can establish up to 12 short-duration OPs (less than 12 hours in duration).17

NOTE: The maximum six long-duration OPs the troop can occupy is a function of18

personnel required to perform the following tasks:19

• Man the actual OP.20

• Maintain radio communications.21

• Provide local security.22

• Conduct dismounted patrols, as required.23

• Conduct resupply.24

• Perform maintenance.25

• Sleep/rest.26

27

COUNTERRECONNAISSANCE28

29

Counterreconnaissance is an inherent task in all security operations.30

Counterreconnaissance is not a mission. It is the sum of actions taken at all echelons31

to counter threat reconnaissance and surveillance (R&S) efforts through the depth32

of the AO. Counterreconnaissance denies the threat information about friendly units.33

It is both active and passive and includes combat action to destroy or repel threat34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-187-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

4-9

Screening is largely accomplished by establishing a series of OPs and1

conducting patrols to ensure adequate surveillance of the assigned sector. Screens2

are active operations. Stationary OPs are only one part of the mission. Employing3

patrols (mounted and dismounted), aerial reconnaissance (TUAV), ground-based4

sensors (GSR, IREMBASS), intelligence from space-based sensor systems, and5

OPs relocated on an extended screen ensure that continuous overlapping6

surveillance occurs. Inactivity in an immobile screen promotes complacency.7

Critical Tasks8

To achieve the intent of a screen mission, the troop must accomplish the9

following critical tasks:10

• Maintain continuous surveillance of all assigned NAIs or avenues of11

approach in sector (IAW the commander’s critical information requirements12

[CCIR] and the R&S plan) with organic assets and, when augmented, with13

TUAVs and ground sensors. METT-TC and IPB will establish the time14

requirements for how and when NAIs and avenues of approach are15

observed.16

• Destroy or repel all threat reconnaissance elements within capabilities and17

based on the commander’s guidance (engagement/destruction criteria).18

Identify threat reconnaissance units and, in coordination with other combat19

elements, destroy them with reach-back precision munitions or attached20

units while not compromising scouts or the brigade.21

• Locate the lead elements that indicate the threat’s main attack orientation22

and direction prescribed in the threat’s order of battle based off the S2’s23

IPB. Provide early warning of threat approach by acquiring information24

deep, in coordination with aerial reconnaissance and ground surveillance25

sensors to be handed over to reconnaissance OPs when necessary.26

• Maintain contact with the threat’s lead element and be prepared to displace27

and report its activities (security drill).28

29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-192-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

4-11

Command guidance should address each phase of the operation and cover at1

least the following:2

• Location/orientation/width of the screen.3

• Depth of troop sector.4

• Duration of the screen.5

• Method of movement to and occupation of the screen.6

• Location and disposition of the friendly force being screened.7

• Engagement/destruction criteria.8

• Displacement/disengagement criteria.9

• Follow-on missions.10

• Positioning and orientation guidance for GSRs, TUAVs, or other sensors (if11

attached).12

• Positioning and orientation guidance for the FIST and /or STRIKERs.13

Considerations14

15

In conjunction with the commander’s guidance, the following paragraphs16

describe the issues that must be considered when developing and completing the17

plan and executing the screen mission.18

19

Time Screen Must Be Established. The time the screen must be set and20

established will influence the troop’s method of deploying to and occupying the21

screen.22

23

Movement to Screen. If the screen mission is the result of a previous tactical24

maneuver such as zone reconnaissance, the troop will essentially be postured to25

begin screening from present positions. This situation occurs frequently, and may be26

the result of a FRAGO to halt at a specified phase line.27

If the troop is not currently set on the screen, obviously deployment to the28

screen must occur before actually beginning the screen mission. Time determines the29

method of occupying the screen. Thorough analysis of METT-TC will determine30

which deployment technique or combination of techniques best meets mission31

requirements.32

33

Trace and Orientation of Screen. The initial screen is depicted as a phase34

line and often represents the forward line of own troops (FLOT). As such, the35

screen may be a restrictive control measure for movement (limit of advance36

[LOA]); coordination/permission would be necessary to move beyond the line to37

establish OPs or to perform reconnaissance. When occupied, OPs are established38

on or behind the phase line. OPs are given specific orientation and observation39

guidance.40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-194-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

4-19

boundary or place the boundary on a road. Place NAIs, TIRS, or checkpoints1

beyond the screen to focus surveillance and assist in the establishment of OPs. As2

the threat’s mission shifts from reconnaissance to attack, change the focus of3

observation (if necessary, change positions) to gain contact with the new threat4

formations entering the sector. If needed, add additional phase lines to control5

displacement of the troop at five-to-eight kilometer intervals. Place contact points6

at the intersection of the platoon boundary and all phase lines. Place TIRS on the7

map or overlay as described in Chapter 2.8

9

Deploy the reconnaissance platoons abreast and, as terrain allows, establish a10

series of OPs (that provide the greatest observation without compromising11

survivability) along or behind the initial screen, but never forward of it without12

permission. Make it clear to the reconnaissance platoon leaders which avenues of13

approach (depicted as NAIs or checkpoints) they are to observe. Areas between14

OPs need to be routinely checked. When this occurs, have the reconnaissance15

platoon leaders prepare patrol plans for approval and subsequent execution.16

17

When augmented with ground sensors, place these assets to observe avenues of18

approach that are out of visual observation to maximize early detection of the19

threat’s approach. Additionally these assets can be oriented on dismounted avenues20

of approach in restricted terrain. TUAVs should be oriented to look deep to gain21

contact with suspected or detected threat movement. Once the threat main elements22

are identified, TUAVs also assist in the displacement and repositioning of ground23

scouts. The TUAVs maintain contact as the platoons conduct security drills IAW24

the commander’s displacement criteria. TUAVs provide a tremendous target25

acquisition capability for indirect and joint fires. TUAVs and ground sensors can be26

used to develop the situation and hand off targets to the ground scout without27

unexpected contact. The troop commander must plan for and maximize the use of28

additional ISR assets in the surveillance troop. This includes information the29

squadron/brigade will receive from division/corps assets as well as joint and national30

assets (joint surveillance target attack radar system [JSTARS], Guardrail, and other31

imagery intelligence [IMINT] and signal intelligence [SIGINT]).32

33

Position the mortar section to fire from one-third to two-thirds of its maximum34

firing range forward of the initial screen, oriented on the expected threat avenue of35

approach. Establish subsequent firing positions for the mortar section back through36

the sector. Plan positions for the FIST/FSO to best execute fires in support of the37

troop’s counterreconnaissance fight and then to harass and impede the threat’s main38

elements.39

40

Identify positions to deploy scouts in an antiarmor role. Scouts should determine41

ambush locations for their antiarmor assets for defense of their OPs and for42

counterreconnaissance (IAW the commander’s destruction/ engagement criteria).43](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-202-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

5-4

positions, whether offensive or defensive, must be adjusted closer to the area or1

point where the commander intends to focus fires. Another alternative is the use of2

visual or IR illumination when there is insufficient ambient light for passive light3

intensification devices. (NOTE: Vehicles equipped with thermal sights can assist4

dismounted scout and infantry squads in detecting and engaging threat infantry5

forces in conditions such as heavy smoke and low illumination.)6

7

8

Develop Contingencies for Diminished Capabilities9

10

Leaders initially develop plans based on their units’ maximum capabilities; they11

make backup plans for implementation in the event of casualties or weapon damage12

or failure. While leaders cannot anticipate or plan for every situation, they should13

develop plans for what they view as the most probable occurrences. Building14

redundancy into these plans, such as having two systems observe the same sector,15

is an invaluable asset when the situation (and the number of available systems)16

permits. Designating alternate sectors of fire provides a means of shifting fires if17

adjacent elements are knocked out of action.18

19

20

FIRE CONTROL PROCESS21

22

To successfully bring direct fires against a threat force, commanders and leaders23

must continuously apply the steps of the fire control process. At the heart of this24

process are two critical actions: rapid, accurate target acquisition and the massing25

of fire to achieve decisive effects on the target. Target acquisition is the detection,26

identification, and location of a target in sufficient detail to permit the effective27

employment of weapons. Massing entails focusing fires at critical points and then28

distributing the fires for optimum effect. Target acquisition is an inherent function of29

the recce troop. The fundamentals and critical tasks associated with reconnaissance30

and security missions (see Chapters 3 and 4) are the basis of target acquisition and31

should be applied. However, the following discussion examines target acquisition32

and how it applies to massing of fires. Use these basic steps of the fire control33

process:34

• Identify probable threat locations and determine the threat scheme of35

maneuver.36

• Determine where and how to mass (focus and distribute) fire effects.37

• Orient forces to speed target acquisition.38

• Shift fires to refocus or redistribute their effects.39

NOTE: Refer to FM 3-91.3 [FM 71-1] for detailed direct fire control information.40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-231-320.jpg)

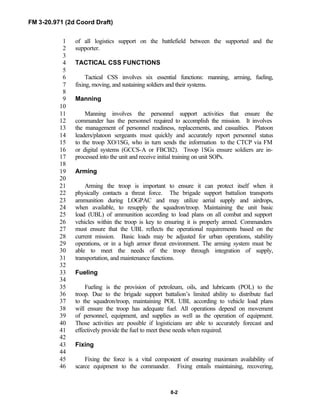

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

5-5

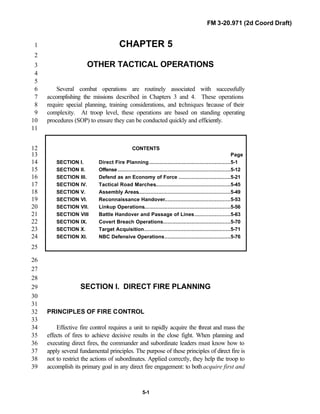

1

2

Identify Probable Threat Locations and Determine the Threat3

Scheme of Maneuver4

5

Acquiring the threat is a precursor to direct fire engagement; however, units will6

not always be able to see the threat and they will not always have additional sensor7

assets to give early warning of the threat’s advance. Rather, the acquisition of the8

threat will often be dependent on recognition of very subtle indicators that may be9

especially difficult to see while moving. Examples include exposed antennas,10

reflections from the vision blocks of threat vehicles, small dust clouds, smoke from11

vehicle engines, or fires from ATGMs or tanks.12

13

Because of the difficulty of target acquisition, the troop commander must14

develop unit surveillance plans to assist the team in acquiring the threat. He must15

also be prepared to apply these techniques to help orient other friendly forces.16

Techniques for unit surveillance, target acquisition, and orientation of subordinate17

elements are discussed in detail in this chapter and on a larger scale in Chapters 318

and 4. Target acquisition at the crew level and crew gunnery techniques are19

discussed in detail in FM 3-20.98 [FM 17-98-2], the reconnaissance platoon20

manual, and applicable gunnery manuals.21

22

The commander and subordinate leaders plan and execute direct fires based on23

their estimate of the situation. An essential part of this estimate is the analysis of the24

terrain and the threat force, which aids the commander in visualizing how the threat25

will attack or defend a particular piece of terrain. A defending threat’s defensive26

positions or an attacking threat’s support positions are normally driven by27

intervisibility. Typically, there are limited points on a piece of terrain that provide28

both good fields of fire and adequate cover for a defender. Similarly, an attacking29

threat will have only a limited selection of avenues of approach that provide30

adequate cover and concealment. Coupled with available intelligence, an31

understanding of the effects of a specific piece of terrain on maneuver will assist the32

commander in identifying probable threat locations and likely avenues of approach33

both before and during the fight. Figure 5-1 illustrates the commander’s analysis of34

threat locations and scheme of maneuver; he may use any or all of the following35

products or techniques in developing and updating the analysis:36

• A SITEMP based on the analysis of terrain and threat.37

• A spot or contact report on threat locations and activities.38

• Reconnaissance of the area of operations.39

40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-232-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

5-13

deprive the threat of resources, to gain information, to deceive and divert the threat,1

to hold the threat in position, to disrupt a threat attack, and to set up conditions for2

future successful operations.3

4

FUNDAMENTALS5

6

Successful offensive operations have four fundamentals.7

• Surprise. Strike the threat at the time and place or in a manner that is least8

expected.9

• Concentration. Mass available forces; strive for overwhelming superiority10

in men, weapons, and firepower. With concentration, however, vulnerability11

becomes a factor. A force that is dispersed is much more survivable. The12

commander must maintain a high sense of situational awareness to anticipate13

the conditions of battle that will allow him to mass at the critical point, kill14

the threat, and quickly disperse to survive.15

• Tempo. Tempo is the rate of speed of military action. Controlling or altering16

the rate is essential for maintaining the initiative. Tempo can be fast or slow,17

depending on the capabilities of the troop relative to those of the threat.18

Commanders must adjust tempo to ensure synchronization.19

• Audacity. Boldness in the plan’s execution is key to success in offensive20

operations. Commanders should understand when and where they are21

taking risks, but must not become tentative when executing their plan.22

23

HASTY ATTACK24

25

A hasty attack is conducted with a minimum of preparation to defeat a threat26

force that is not prepared or deployed to fight. It is a course of action routinely27

employed in reconnaissance operations to seize or retain the initiative, or to sustain28

the tempo of operations. A hasty attack can be executed while the troop is engaged29

in a zone reconnaissance mission.30

31

Critical Tasks32

33

To successfully execute a hasty attack, the following critical tasks must be34

accomplished:35

• Reconnoiter and determine the size, composition, and orientation of the36

threat force (with tactical unmanned aerial vehicles [TUAV], ground37

surveillance radar [GSR], mounted and dismounted scouts).38

• Determine if the objective threat force is supported by other units nearby39

(using TUAV, GSR, scouts).40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-240-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

5-14

• Find a high-speed, covered and concealed approach into the threat’s1

flank(s) (using TUAV, GSR, scouts).2

• Establish a maneuver element (usually an armored element attached from3

the brigade) to move to a position of advantage and attack the threat by4

fire.5

• Establish a base-of-fire element (usually one or, if possible, two platoons) to6

defeat or suppress all observed threat AT weapons with long-range direct7

and indirect fires before the maneuver force deploys into its attack.8

• Isolate the objective threat force from other mutually supporting units with9

indirect fires (usually with smoke and HE mortar/FA ammunition, or a scout10

platoon).11

• Attack the threat by fire or by fire and maneuver, and defeat it.12

• Once the attack is completed, immediately establish hasty defensive13

positions and OPs on high-speed avenues of approach into the troop14

position.15

Techniques16

17

Each critical task has a time at which it will be accomplished in relation to all18

other critical tasks. A good hasty attack depends on the commander’s sense of19

timing and on his ability to employ his forces to accomplish the tasks in the proper20

sequence. The commander has to synchronize—concentrate and apply different21

forms of combat power against the threat at the right times and places. The decision22

to conduct a hasty attack is usually made after a reconnaissance of a threat force,23

and dispositions show that winning requires a quick strike with little preparation.24

Under no circumstances should a hasty attack be ordered unless the threat position25

has been thoroughly reconnoitered and the individual positions are known. Tactics26

for conducting a hasty attack have three features:27

• Known or suspected threat AT weapons are suppressed and destroyed28

with direct and/or indirect fires before the maneuver force is committed.29

• The threat is forced to fight in two directions.30

• The threat is suppressed and unable to react.31

32

Establishing the Conditions for a Hasty Attack33

34

While conducting other missions, scouts will often make contact with a threat35

force. In developing the situation (based on the engagement criteria from36

commander’s reconnaissance guidance [see Chapter 3], what is a troop fight versus37

a platoon fight), a scout platoon may recommend hasty attack as a course of action38

to the troop commander, who decides to execute the recommended course of39](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-241-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

5-32

• Displacement to alternate, supplementary, or successive OPs/BPs.1

• Cross-leveling or resupply of Class V.2

•• Evacuation of casualties.3

NOTE: The troop commander should coordinate the troop rehearsal with the4

squadron to ensure other units’ rehearsals are not planned for the same5

time and/or location. Coordination will lead to more efficient use of6

planning and preparation time for all the squadron’s units. It will also7

eliminate the danger of misidentification of friendly forces in the rehearsal8

area, which could result in fratricide.9

10

11

DEFENSIVE SCHEMES OF MANEUVER12

13

There are three basic schemes of maneuver the commander can use in14

designating a course of action for a defensive mission:15

• Defend from a troop battle position.16

• Defend in troop sector.17

• Delay.18

19

These schemes of maneuver center on the use of battle positions and sectors for20

subordinate platoons, or a combination of the two. For a detailed discussion of21

defensive operations, see FM 3-40 [FM 100-40 (draft)] or FMs 3-20.95 [FM 17-22

95] and 3-20.97 [FM 17-97].23

24

Defend From a Troop Battle Position25

26

When properly augmented, the troop may defend from a battle position. This is27

usually done when the threat situation is clear and there is only one avenue of28

approach. In this scheme of maneuver, the troop commander retains most of the29

authority for fighting the battle. The troop commander must understand his higher30

commander’s intent and concept to prevent holding the troop in place and risking its31

destruction. This mission is normally assigned when the higher commander elects to32

concentrate the direct fires of the troop or squadron/brigade within an engagement33

area. The troop cannot maneuver outside the position without the higher34

commander’s permission. Within the battle position, the troop commander positions35

his platoons to concentrate all direct fires where the squadron has specified. The36

troop fights to retain the position unless ordered by the higher commander to37

counterattack or withdraw.38

39

40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-259-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

5-51

available, an advance party should conduct a ground reconnaissance. The troop1

SOP should have a standard assembly area occupation drill and layout.2

QUARTERING PARTY3

Special care is taken to ensure that FBCB2 communication is possible between4

the quartering party OIC and the troop CP. Prior to quartering party movement,5

the vehicles within the quartering party will display the automated operations overlay6

on their tactical displays. This overlay typically includes the movement route,7

waypoints, specific critical points, and the assembly area. Additional control8

measures, such as contact points, coordination points, observation points, and9

screen lines, may be included to enhance control and/or security. If fire support,10

obstacle, and threat overlays are also available, quartering party members should11

study and store these in their FBCB2.12

During movement, the quartering party leader passes critical information to the13

troop CP via FBCB2 or FM voice. The quartering party annotates changes to the14

published route on the FBCB2 overlays and updates the troop CP by forwarding15

overlay updates.16

17

Normally, the XO or 1SG will lead the quartering party into the AA. When the18

quartering party arrives at the forward AA, they must—19

• Reconnoiter the area. If the area is not suitable, report immediately and20

provide recommendations.21

• Organize the area. Select locations for all elements of the troop based on22

the commander’s instructions or as terrain, cover, and concealment dictate.23

Select general locations for vehicles. Vehicle commanders and the chain of24

command refine these positions when they arrive.25

• Improve and mark entrances, exits, and internal routes.26

• Update the overlay to reflect any changes in the location of the assembly27

area and any obstacles encountered.28

• Perform guide duties as required. Platoon representatives guide their29

elements into position after clearing the release point.30

NOTE: Refer to FM 3-20.98 [FM 17-98] for a detailed discussion of quartering31

party activities.32

33

34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-278-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

5-59

When possible, the commanders of the units involved establish liaison. If the1

threat is between the forces conducting a linkup, this liaison may not occur and2

coordination is then accomplished by radio or through FBCB2. During the3

operation, the two units attempt to maintain continuous radio contact with each4

other or the higher headquarters. As a minimum, the units exchange the following5

information:6

• Threat and friendly situation.7

• Locations and types of obstacles.8

• Fire support plans (especially RFL and coordinated fire line [CFL]).9

• Possible routes to the objective.10

• Communications.11

• Recognition signals.12

• Contingency plans.13

14

Every effort should be made to establish a face-to-face liaison. If a face-to-15

face linkup is not possible, establish a reliable digital and/or voice linkup to16

exchange critical information. As the distance closes between the forces, the17

requirement to maintain close liaison and exchange information increases. Linkup18

operations frequently require a passage of lines. Once through, the troop moves to19

the linkup. The action is characterized by speed, aggressiveness, and boldness.20

Threat forces that threaten the successful accomplishment of the mission are21

destroyed. Others are bypassed and reported.22

23

The communication plan includes radio frequencies, net IDs, EPLRS needlines,24

host files required to conduct the linkup (if units are from different maneuver control25

systems), and COMSEC variables for communication between the two forces. It26

must prescribe day and night identification procedures, including primary and27

alternate means. Visual signals such as flares or panels may be used during daylight,28

and flashlights or infrared devices may be employed during darkness. To prevent29

friendly troops from exchanging fires, recognition signals must be established. They30

may be pyrotechnics, armbands, vehicle markings, panels, colored smoke,31

distinctive light patterns, and passwords. Using the BCIS and situational awareness32

via FBCB2 greatly enhances friendly recognition.33

34

Logistical requirements may be greater during linkup operations than during35

other offensive actions. Additional considerations for linkup include—36

• Distance to the linkup.37

• Time the objective area is to be held.38](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-286-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

5-71

• Troop density. The passing troop commander should plan for multiple1

routes of passage to ensure rapid movement and to avoid congestion.2

• Traffic control. Guides from the stationary unit pick up passing elements at3

each contact point and guide them through the position. The passing unit4

commander tells the stationary unit the type, number, and order of vehicles5

passing through each contact point.6

• Communications. Leaders exchange SOI and FBCB2 IP address7

information and mutually agreed upon recognition signals.8

• CSS. The troop commander submits the required digital reports to effect9

the evacuation of casualties, EPWs, vehicles, and resupply of fuel and10

ammunition. The stationary unit usually provides immediate CSS only.11

(Usually the troop commander will coordinate a forward passage of lines12

and the XO coordinates a rearward passage. If the troop commander or13

XO is not available, a platoon leader or platoon sergeant should perform14

these liaison functions. In this case, the liaison officer must be thoroughly15

briefed on the situation and follow the checklist in the troop SOP.)16

17

18

SECTION IX. COVERT BREACH OPERATIONS19

The covert breach is a special breaching operation conducted by scouts,20

engineers, or dismounted infantry during limited visibility. It relies on stealth, quiet21

lane reduction techniques, and dismounted maneuver to achieve surprise and to22

minimize casualties. The limited dismounted capability of the troop must be weighed23

during breach operations to determine if surprise can be achieved. FM 3-34.2 [FM24

90-13-1] outlines the doctrine for combined arms breaching operations and covers25

all four types of breaches in explicit detail.26

The engineer reconnaissance element placed OPCON to the troop aids in27

breach operations. This element provides the commander technical advice as to the28

effort and equipment required to breach obstacles. The actual breaching abilities of29

the engineer reconnaissance element are limited to manual methods.30

31

A covert breach may be executed when stealthy reconnaissance is key to the32

infiltration efforts of the troop and surprise is integral to the assault of a position or33

follow-on attack. The covert breach will also be conducted during climatic34

conditions that support such operations (e.g., limited visibility). The commander will35

also use a covert breach when his available combat power is not needed to support36

a follow-on assault.37

38](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-298-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

5-72

Obstacles at the breach site are normally reduced by a reduction team using1

silent techniques, such as:2

• Marking mines.3

• Cutting wire.4

• Reshaping an antitank ditch with shovels.5

• Setting explosive charges and waiting for a signal or trigger to detonate6

them.7

The difference between the covert breach and other breaching operations is8

execution of the breaching fundamentals (i.e., SOSR—suppress, obscure, secure,9

reduce). Suppression is planned, but remains “on call” until the assault begins.10

Obscuration is achieved through the use of smoke or conducting the operations11

under limited visibility. Security is provided by the security team of the breach force12

and includes early warning and covering the withdrawal of the reduction team. See13

FM 3-11.50 [FM 3-50] for more detailed information on smoke operations.14

15

SECTION X. TARGET ACQUISITION16

17

Target acquisition (TA) is the detection, identification, and location of a target in18

sufficient detail to permit the effective employment of weapons. With the advances19

of precision munitions and the systems to rapidly deliver them from relatively safe20

locations, the likelihood of the troop’s reconnaissance mission being focused on21

target acquisition is increased exponentially. The process itself is embedded in all22

reconnaissance operations.23

24

Target acquisition, development through execution, is a critical task in all troop25

missions. The information that supports the troop and its higher headquarters26

targeting and fire support plan is a major portion of the information passed during a27

reconnaissance handover. Target acquisition may be an objective or a focus of a28

reconnaissance mission. ISR assets gather targeting information and targets by29

using all available means. These means include, but are not limited to:30

31

• OH-58A/C and OH-58D helicopters.32

• TUAV.33

• STRIKERs.34

• FISTs.35

• Scouts.36](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-299-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

5-77

1

SECTION XI. NBC DEFENSIVE OPERATIONS2

3

NBC defensive operations reduce casualties and damage to equipment and4

materiel, and minimize confusion and interruption of the troop’s mission in the event5

of threat NBC attacks. These operations are performed concurrently with all6

combat operations to preserve the fighting strength of the troop.7

8

The troop’s NBC defense personnel are an NBC trained officer (usually the9

platoon leader), an MOS-qualified NBC NCO, and an enlisted alternate.10

11

The NBC officer supervises troop NBC defense activities and assists the12

commander in training NBC equipment operators. The NBC NCO and his13

alternate directly supervise radiological monitoring, chemical detection, and14

decontamination operations. During combat operations, the NBC NCO is located15

in the troop CP where he—16

• Receives, prepares, evaluates, and digitally disseminates information and17

reports threat and friendly NBC attacks via FBCB2 and FM.18

• Supervises employment of detection, monitoring, and surveying operations.19

• Maintains unit radiation exposure status records.20

• Assists the troop commander in analyzing guidance from the21

brigade/squadron for mission, threat, and weather as they affect NBC22

operations and recommends appropriate MOPP level based on this23

information.24

To facilitate operations in an NBC environment, all soldiers must be proficient in25

operating the assigned NBC detection equipment. The troop SOP may designate26

teams for NBC operations based on MTOE equipment authorizations. See FM 3-27

11 [FM 3-100] for detailed discussions on NBC techniques and procedures for28

operations in an NBC environment.29

30

31

NOTE: Refer to Appendix B for a detailed discussion of troop NBC operations.32

33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-304-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

6-1

CHAPTER 61

COMBAT SUPPORT2

The troop commander must know the capabilities and limitations of CS3

assets, how to properly employ them, effectively integrate them into his4

overall scheme of maneuver, and ensure they are synchronized during5

operations.6

With digitization, CS elements possess greater situational awareness and7

are better able to support troop tactical situations. The interoperability of8

these maneuver and CS digital systems enhances the brigade/squadron and9

troop commander’s ability to quickly synchronize operations and apply10

superior combat power at the decisive place and time on the battlefield.11

12

CONTENTS13

Page14

SECTION I. Intelligence ....................................................................6-115

SECTION II. Fire Support/Target Acquisition .....................................6-1616

SECTION III. Army Aviation ................................................................6-3617

SECTION IV. Tactical Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Platoon ...................6-6318

SECTION V. Multi-Sensor Platoon......................................................6-6719

SECTION VI. IBCT Infantry Rifle Company..........................................6-7320

SECTION VII. Mobile Gun System Platoon...........................................6-8321

SECTION VIII. Infantry Battalion Reconnaissance Platoon ...................6-8622

SECTION IX. Antitank Platoon/Company ............................................6-8823

SECTION X. NBC Reconnaissance .....................................................6-9224

SECTION XI. IBCT Engineer Company................................................6-9325

SECTION XII. Air Defense ....................................................................6-9826

27

SECTION I. INTELLIGENCE28

While only the recce troop has 97Bs (human intelligence [HUMINT]29

collectors) assigned, the BRT utilizes HUMINT as well. Reconnaissance30

organizations have used information gained from locals and prisoners from31

the beginning of organized warfare. HUMINT operations are an integral part32

of the troop’s reconnaissance effort. The operational environment of the troop33

offers a wide array of human intelligence sources, to include enemy prisoners34

of war (EPW), detained persons, refugees, local inhabitants, and friendly35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-305-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

6-5

HUMINT Collection in Support of Stability Operations or Support1

Operations2

The primary focus of the HUMINT collectors during stability operations3

or support operations is intelligence support for force protection. Centralized4

management and databases are key to successful HUMINT operations in5

support of force protection. The HUMINT collectors organic to the recce6

troop will normally be allocated to individual reconnaissance squads, as7

necessary, to provide a language and tactical questioning ability, to translate8

and exploit foreign documents, and to identify individuals as potential9

counterintelligence (CI) sources to be more fully exploited by the HUMINT10

platoon in the MI Company. The HUMINT teams establish a network of11

force protection sources, debrief casual sources, and interview/debrief local12

national employees to increase the security posture of US forces, to provide13

information in response to command collection requirements, and to provide14

early warning of threats to US forces. The HUMINT collectors develop both15

the overall HUMINT picture and the more specific threat intelligence16

collection (CI) picture. Additionally, the HUMINT collector is in the position17

to articulate the friendly force’s position and draw commonality with the local18

populace while dispelling antifriendly propaganda.19

DOCUMENT EXPLOITATION OPERATIONS20

Document exploitation (DOCEX) is the extraction and exploitation of21

information with intelligence value from documents, to include all types of22

written or recorded media. The HUMINT teams perform limited exploitation23

of documents for information of immediate tactical interest dealing primarily24

with documents found on or in immediate association with EPWs, civilian25

detainees, refugees, and other HUMINT sources. In their traditional role,26

HUMINT collectors review captured orders and maps. In stability operations,27

as an example, they monitor election posters in different ethnic areas.28

The exploitation of documents captured on or in association with29

HUMINT sources is performed in conjunction with the initial tactical30

questioning of these individuals. Documents that cannot be exploited by the31

HUMINT teams in a timely fashion (due to their size or technical nature) are32

scanned and transmitted to higher for translation and exploitation.33

See FM 2-22.3 [FM 34-52] and FM 2-00.5 [FM 34-5] for more detailed34

information on HUMINT operations.35

TACTICAL QUESTIONING36

When conducted properly, tactical questioning elicits valuable, timely and37

accurate information from the local populace. When conducted improperly,38

you will confuse the subject, waste time, and receive inaccurate information.39

Tactical questioning must answer who, what, where, when, how, and why.40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fm-3-20-140723131053-phpapp02/85/Fm-3-20-97-the-recce_and_brt_troop_draft-309-320.jpg)

![FM 3-20.971 (2d Coord Draft)

6-12

ISR Integration Platoon1

The MI Company’s ISR Integration Platoon conducts ISR requirements2

management; HUMINT collection, planning, and deconfliction; and3

multisensor visualization (through the common ground station [CGS]) for the4

brigade commander and staff in support of the brigade S2 section. The platoon5

consists of an ISR Management Team, an S2X Team, and a CGS team. This6

organization allows continuous and dynamic control of the brigade’s ISR7

assets with special capabilities to direct tactical HUMINT operations through8

the S2X and access nonorganic sensors via the CGS.9

ISR Management Team10

The ISR Management Team is responsible for developing, monitoring,11

and dynamically adjusting the brigade’s ISR collection effort. It participates12

in the brigade staff wargaming and synchronization session to extract ISR13

requirements that answer the commander’s decision making and targeting14

needs. The team also works closely with the brigade S2 Operations Team to15

identify shortcomings in current and near-term ISR support. With ISR16

requirements for both current and future operations, the team develops and17

adjusts ISR collection plans, orders, and requests to position ISR assets to18

deliver combat information, targeting data, and intelligence to the commander19

and staff.20

By simultaneously monitoring the current situation and future planning,21

the team can rapidly recognize and redirect ISR assets to respond to situations22

that are significantly divergent from the assumed threat COAs that led to the23