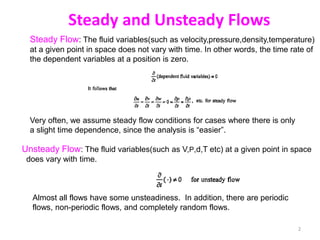

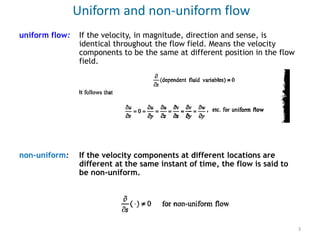

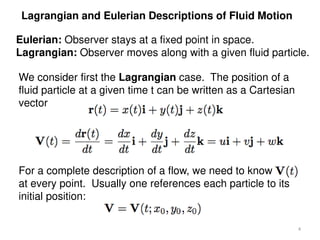

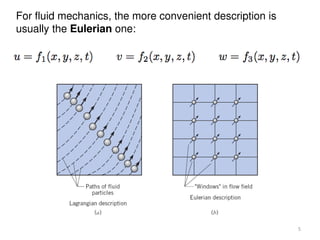

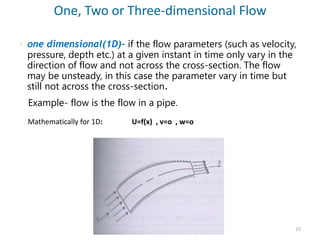

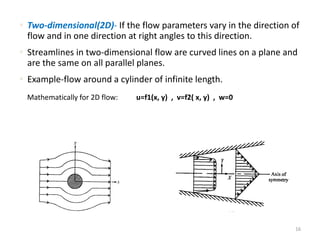

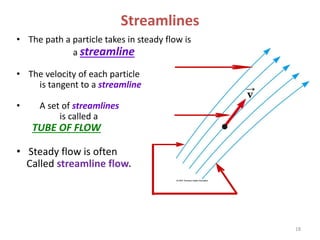

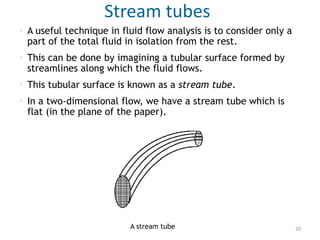

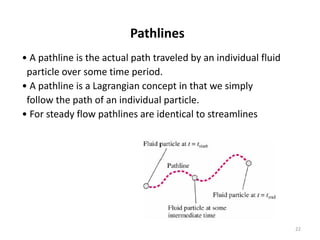

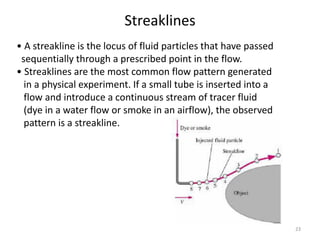

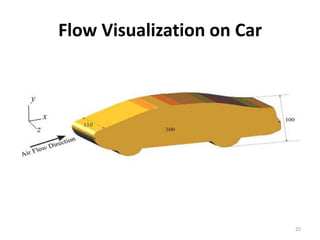

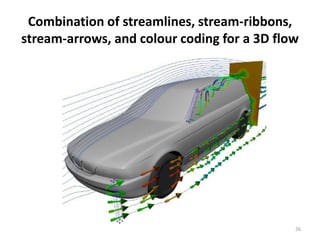

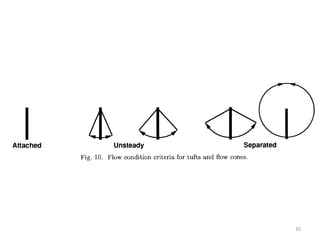

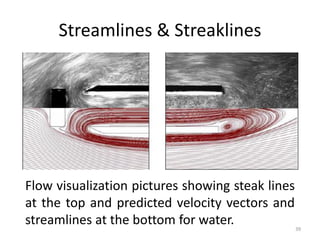

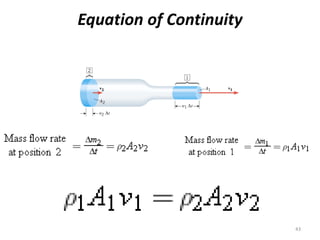

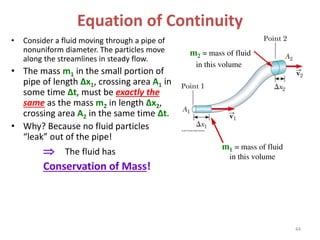

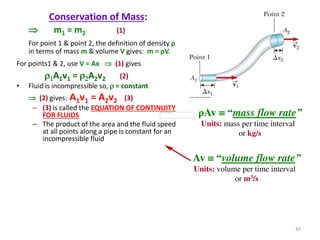

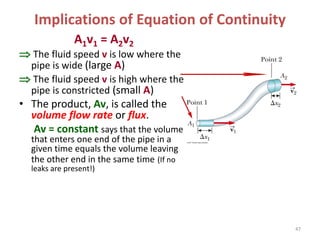

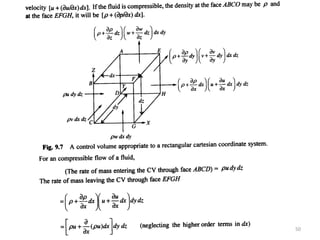

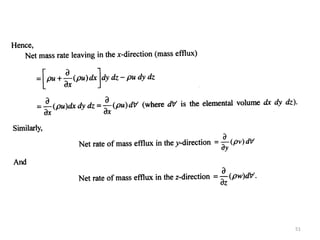

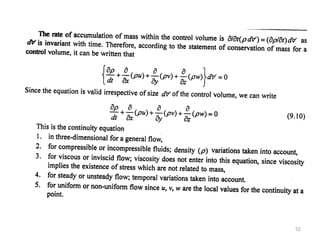

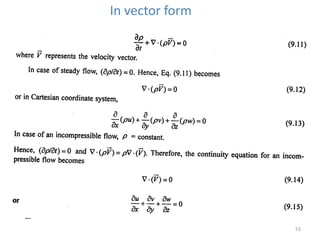

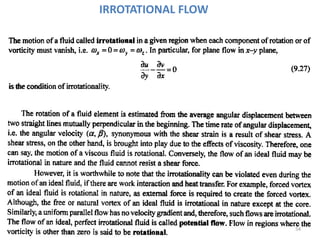

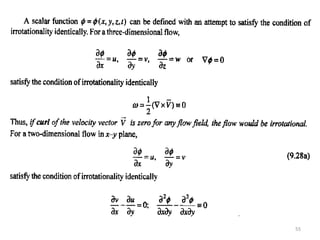

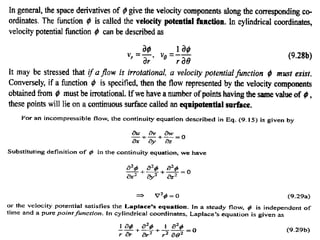

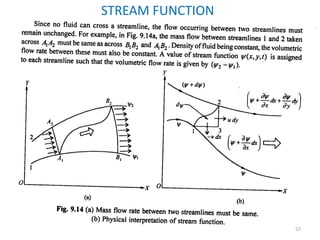

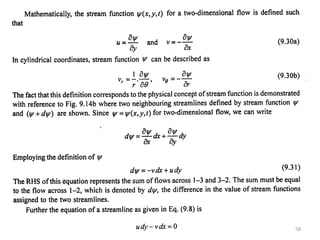

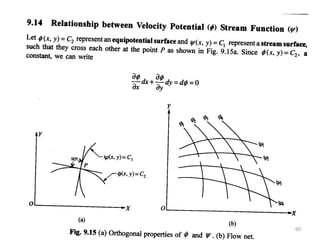

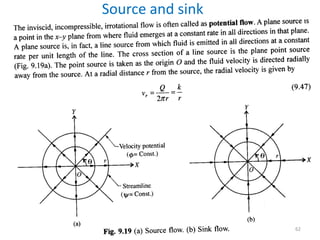

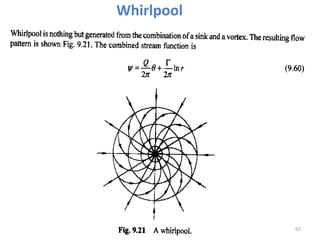

The document covers fluid kinematics, detailing the differences between steady and unsteady flows, uniform and non-uniform flows, and two main descriptions of fluid motion: Lagrangian and Eulerian. It explains the concepts of streamlines, pathlines, streaklines, and the equation of continuity in fluid dynamics, emphasizing conservation of mass in fluid systems. Various visualization techniques and representations of flow patterns are also discussed, including the use of stream tubes and different flow conditions.