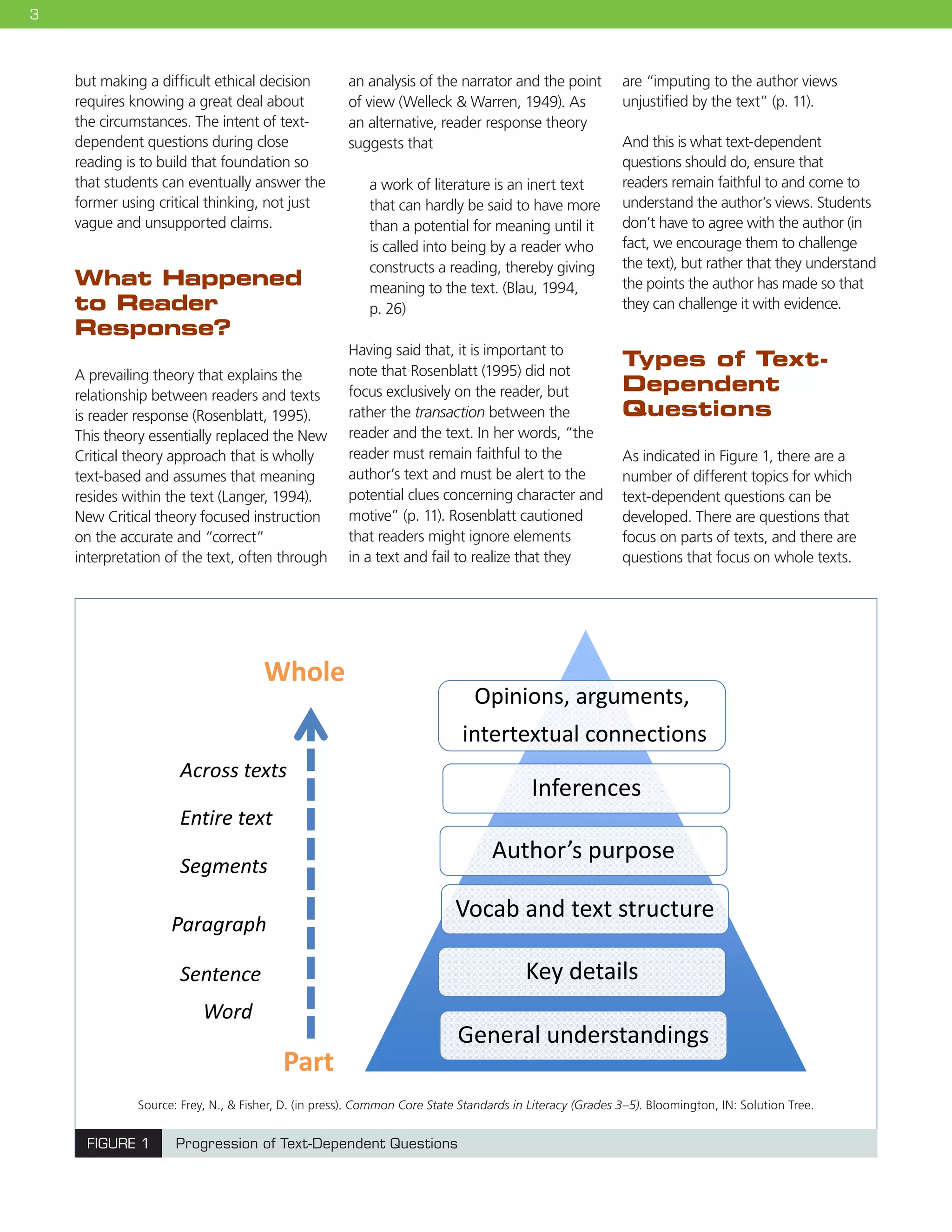

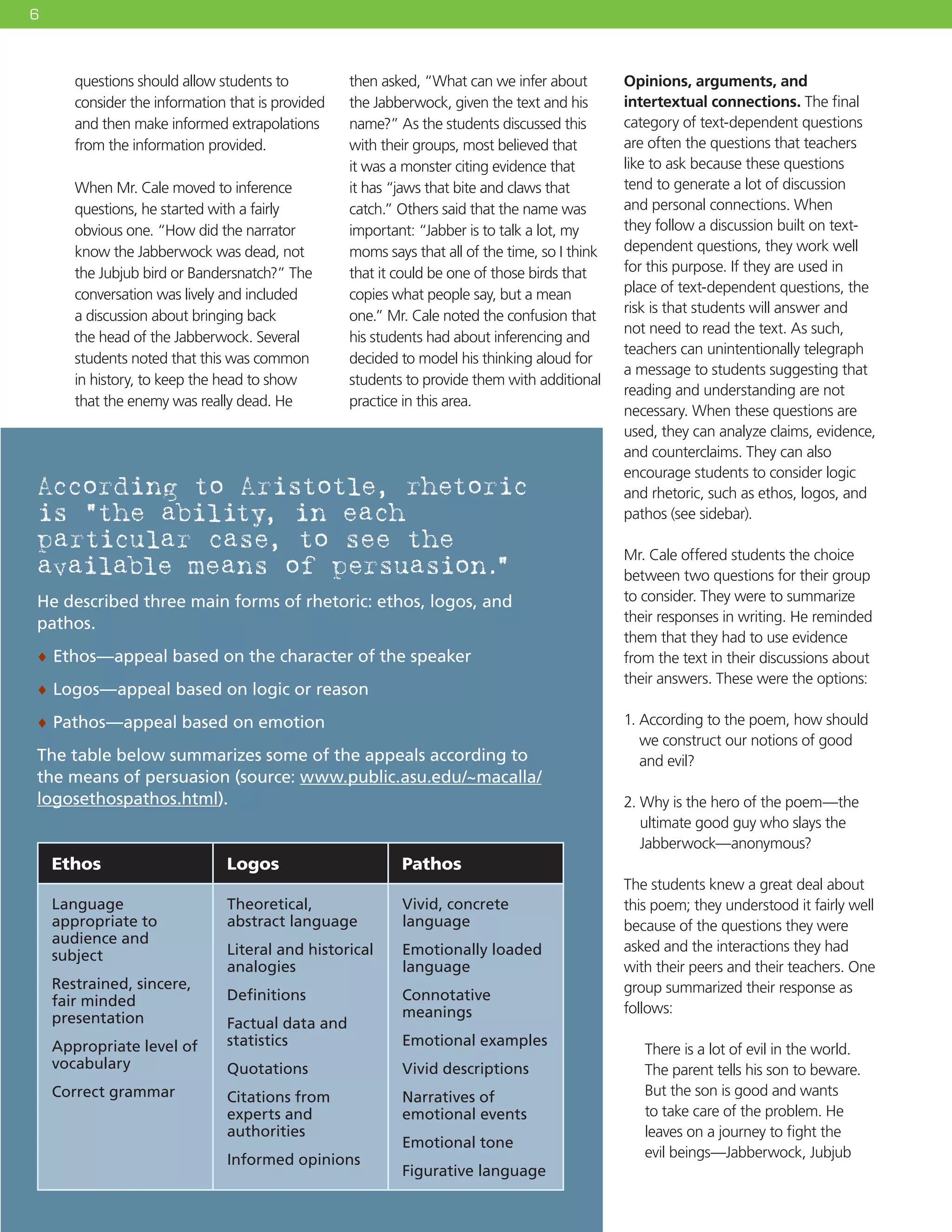

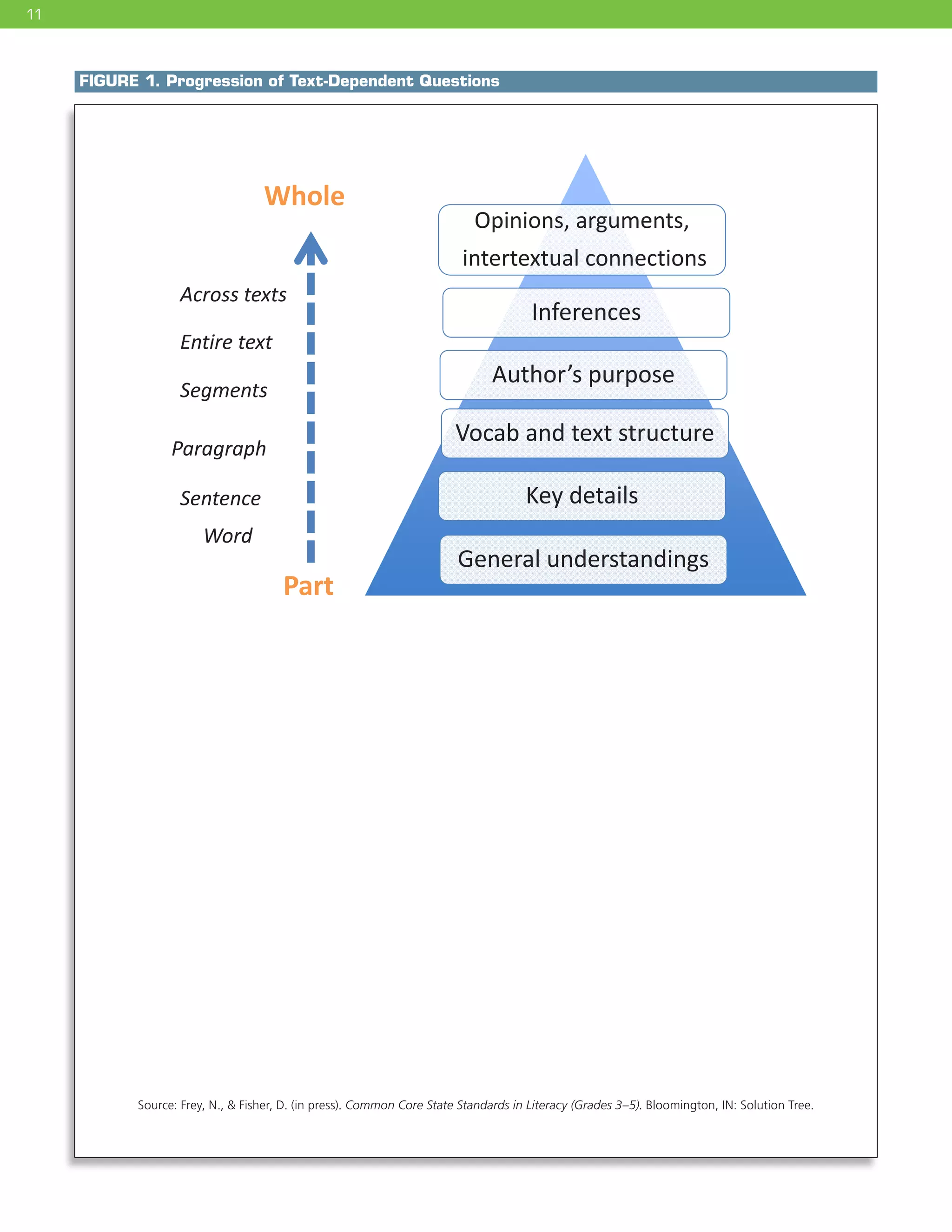

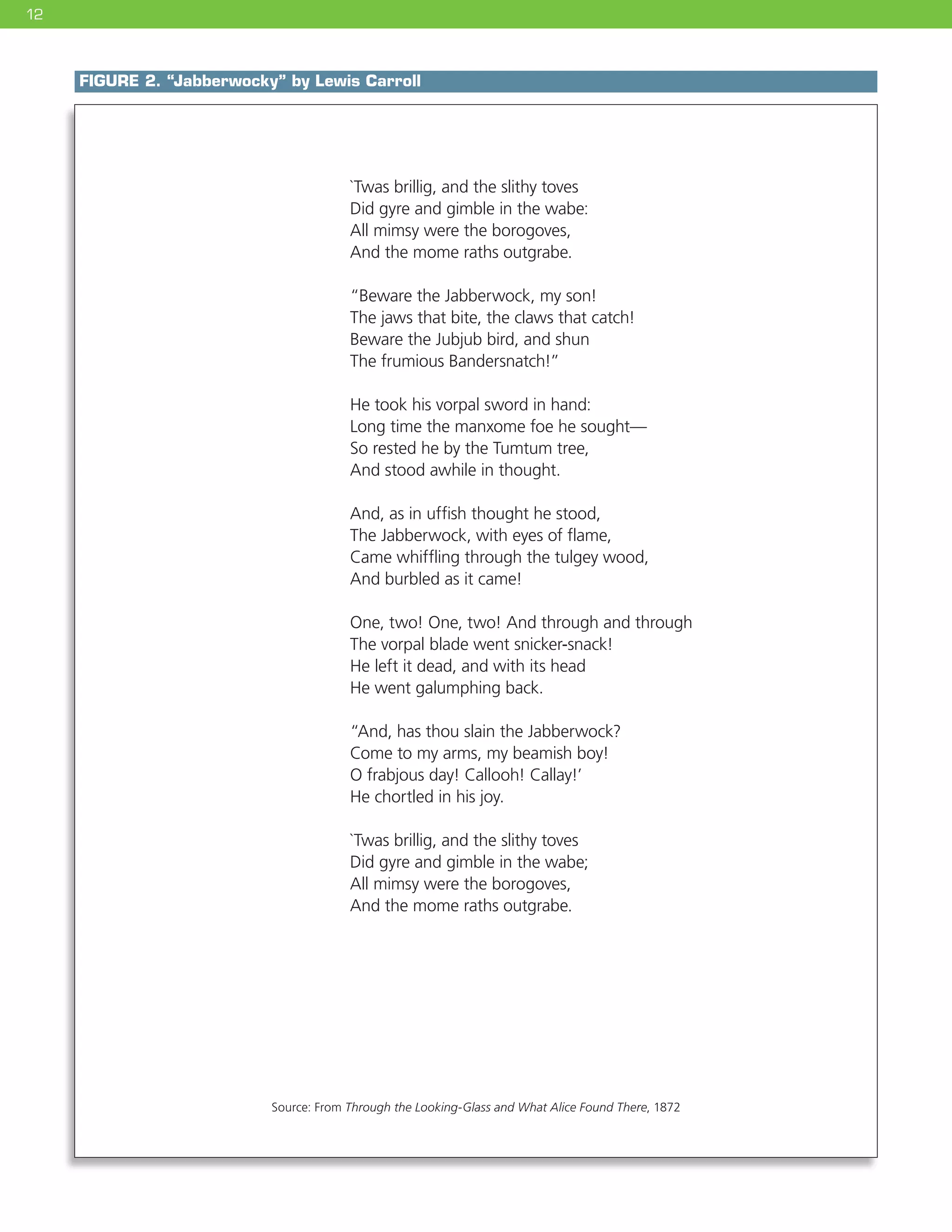

The document discusses text-dependent questions that require students to provide evidence from the text to justify their responses. It explains that text-dependent questions ensure students have carefully read and understood the text, rather than answering questions without reading. The document provides examples of different types of text-dependent questions teachers can ask, from general understanding questions to questions about key details, inferences, and opinions. It also gives an example of text-dependent questions a teacher asked about the poem "Jabberwocky".