This document outlines Lori Dixon's program of study and professional development plan for a Master of Science in Nursing degree with a specialization in nursing informatics. It provides background on her nursing career spanning over 25 years, from becoming a registered nurse to her current role in clinical informatics. It describes her motivation to further her education to make more of an impact on patient care through her informatics work. The plan details the courses she will take to complete the degree and her goals of gaining skills in APA writing style and critically reviewing research to support her work in clinical trials and research.

![Developing a Health Advocacy Campaign

Nurses have an ethical responsibility to be active in advocacy. Nurses should address

issues with populations, and speak out to make changes in disparities or inequities to access to

care (Laureate Education, Inc. [Laureate], 2012). The purpose of this paper is to describe a

population health issue, identify the population it affects, review current health advocacy

programs and develop a health advocacy program.

Population Health Issue

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) is designed to provide healthcare for all Americans.

The emphasis is “all Americans.” To be eligible for care, an immigrant must have legal

immigrant status ("ACA Latinos," 2014). Migrant workers in the United States are a mixture of

legal and illegal workers. There are nearly a million farm workers, and 25-50% are illegal

immigrants (Baragona, 2010). Farm workers have families that travel with them from state to

state.

Patients go to a new provider, and the first thing that happens is the collection of their

health history. The new provider may ask for a release to get medical records from a previous

provider. Illegal or legal migrants move so frequently that they do not have a primary health

care provider. They may seek emergency or urgent care when they become ill, and children may

not receive important check-ups. There are barriers to healthcare such as unable to speak

English, the cost of care, availability of care, and distrust of healthcare workers. Hispanic

workers have health issues such as diabetes, sexually transmitted disease, teenage pregnancy,

and cirrhosis (Peach, 2013). The health issue is a lack of healthcare due to barriers that prevent

migrant workers and their families from receiving consistent healthcare. By traveling from state

to state, there is no history of their medical care for new providers to review.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4b8d9c7d-55a0-4705-8f5f-53f25e3bcf63-151104213538-lva1-app6891/85/FinalPortfolioDraft-September-1-2015-17-320.jpg)

![Laureate Education, Inc. (Producer). (2012,). The needle exchange program [Interview

transcript]. Retrieved from

https://class.waldenu.edu/webapps/portal/frameset.jsp?tab_tab_group_id=_2_1&url=%2

F

webapps%2Fblackboard%2Fexecute%2Flauncher%3Ftype%3DCourse%26id%3D_5100

419_1%26url%3D

Mulligan, R., Seirawan, H., & Faust, S. (2010, February). Oral health care delivery model for

underserved migrant children. Journal of the California Dental Association, 38, 115-121.

Retrieved from http://www.cda.org/

National Center for Farmworker Health website. (2014). http://www.ncfh.org/

National Immigration Center website. (n.d.). http://www.nilc.org/

Peach, H. (2013, May 3). Migrant farm-workers and health. Rural and Remote Health, 13, 1-3.

Retrieved from http://www.rrh.org.au

The Affordable Care Act and Latinos. (2014). Retrieved from

http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/facts/factsheets/2012/04/aca-and-latinos04102012a.html

The legislative Process. (2011). Retrieved from http://congress.indiana.edu/legislative-process

Waldeman, H. B., Cannella, D., & Perlman, S. P. (2010, November). Migrant farm workers and

their children. Exceptional Parent, 52-53. Retrieved from www.eparent.com](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4b8d9c7d-55a0-4705-8f5f-53f25e3bcf63-151104213538-lva1-app6891/85/FinalPortfolioDraft-September-1-2015-25-320.jpg)

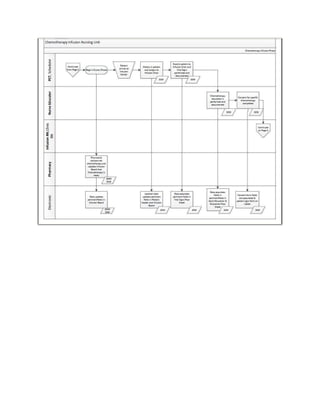

![the results tab in SCM for the physician’s review. The nurse notifies the physician that the

patient is ready to be seen.

Pre-Infusion Physician Process

Page two in the process flow focuses around the physician’s visit with the patient. Prior to

going into the patient’s room, reviews the patient’s lab results to prepare for discussing treatment

options with the patient. If the patient’s Hemoglobin (Hb) ≤11 g/dL or ≥2 g/dL below baseline,

the patient may need a transfusion prior chemotherapy (NCCN Guidelines Version 2.2015 Panel

Members Cancer- and Chemotherapy-Induced Anemia [NCCN Panel], 2014). The flow chart

shows the decision point for no; and the chemotherapy cannot be given, and treatment for anemia

will begin. Or the decision is yes, because the labs show the patient values are within range, and

they can proceed with chemotherapy. The physician will open the progress note, and pull the

labs into the note and notate they have reviewed the labs with the patient. Next the physician

will open ORM through the progress note and review the medications with the patient. The

physician will reconcile the medications, and make any prescription changes needed ("TJC

Patient Safety," 2014). The physician will review the previous chemotherapy administered to the

patient in the treatment summary in SCM. Patient should receive the same chemotherapy dosing

unless there are changes in the patient’s condition. The physician will now order the

chemotherapy protocol for the patient. The nurse now escorts the patient to scheduling to review

the schedule for the week. Schedulers will review with the patient in ES, and the patient can

come anytime during the next day, and scheduler will make changes based on the patient’s

needs. The patient will now proceed to the infusion center.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4b8d9c7d-55a0-4705-8f5f-53f25e3bcf63-151104213538-lva1-app6891/85/FinalPortfolioDraft-September-1-2015-33-320.jpg)

![References

AHRQ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2013). http://healthit.ahrq.gov/health-it-

tools-and-resources/

Morgenstern, D. (n.d.). Clinical workflow analysis - Process defect identification [PowerPoint

slides]. Retrieved from

http://mehi.masstech.org/sites/mehi/files/documents/CPOE_Clinical_Workflow_Analysis

.pdf

NCCN Guidelines Version 2.2015 Panel Members Cancer- and Chemotherapy-Induced Anemia.

(2014). Cancer -and chemotherapy - induced anemia. Retrieved from

http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/anemia.pdf

National Patient Safety Goals Effective January 1, 2014. (2014). Retrieved from

http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/HAP_NPSG_Chapter_2014.pdf

Neuss, M. N., Polovich, M., McNiff, K., Esper, P., Gilmore, T. R., LeFebvre, K. B., Jacobson, J.

O. (2013, March). 2013 Updated American Society of Clinical Oncology/Oncology

Nursing Society Chemotherapy administration safety standards including standards for

the safe administration and management of oral chemotherapy [Supplemental material to

magazine]. Journal Of Oncology Practice, 5s-13s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.000874](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4b8d9c7d-55a0-4705-8f5f-53f25e3bcf63-151104213538-lva1-app6891/85/FinalPortfolioDraft-September-1-2015-37-320.jpg)

![4. Does the documentation in the patient chart provide the data necessary for quality

indicators?

5. Do the physicians need education on documentation in the patient’s chart? What is

the definition of appropriate documentation?

The issue is that the documentation is not supporting the quality indicators or financial

reimbursement. Each of the questions above is background questions, they each look at a piece

of the issue but would not be complete enough to answer the clinical question.

Feasibility

Once the problem is identified for research, the researcher must decide if it is feasible to

research the problem. The following areas must be reviewed, although they may not be

necessary for every research study; time, participant availability, cooperation of others,

equipment, facilities, money, and ability of the researcher (Polit & Beck, 2012). Facilities and

providers will be forced into the ICD-10 changes on October 1, 2015. To provide evidence-

based change in the facility, it is necessary to create a research plan that would take place over

six months. The facility is willing to cooperate with the research plan, and minimal funding will

be needed. Two units will be identified to be part of the study, one will be a control group that

will not have a CDIP assigned to the unit, and the other unit will have a CDIP to educate the

physicians. The participants will be the hospitalists that are assigned to each unit, and the units

selected each uses a different group of hospitalist (Polit & Beck, 2012). The researcher is a

certified CDIP, who has passed their certification exam through the American Health

Information Management Association (AHIMA) (American Health Information Management

Association [AHIMA], n.d.). The current electronic health record (EHR) will be used for the

chart reviews, and the facility will grant the researcher access to the EHR.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4b8d9c7d-55a0-4705-8f5f-53f25e3bcf63-151104213538-lva1-app6891/85/FinalPortfolioDraft-September-1-2015-41-320.jpg)

![References

American Health Information Management Association. (n.d.). Certified documentation

improvement practitioner (CDIP®). Retrieved from http://www.ahima.org/

Battelle. (2011). Quality indicator user guide: Patient safety indicators (PSI) composite

measures V4.3. Retrieved from

http://qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/downloads/modules/psi/v43/composite_user_technical_s

pecification_psi_4.3.pdf

Brown, L. R. (2013). The secret life of a clinical documentation improvement specialist

[Supplemental material]. Nursing, 10-12. doi: 10.1097/01.NURSE.

0000426541.97687.87.

Byrnes, J., & Fifer, J. (2010). A guide to highly effective quality programs. Healthcare financial

Management, 81-87. Retrieved from hfma.org

Carman, M. J., Wolf, L. A., Henderson, D., Kamienski, M., Koziol-McLain, J., Manton, A., &

Moon, M. D. (2013). Developing your clinical question: The key to successful research.

Journal of Emergency Nursing, 39, 299-301. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2013.01.011

Hinderks, J., Vagle, J., & Wolf, J. (2014). Preparing for the true risks of ICD-10. Healthcare

Financial Management, 98-102. Retrieved from hfm.org

Hines, P. A., & Yu, K. M. (2009). The changing reimbursement landscape: Nurses’ role in

quality and operational excellence. Nursing Economic$, 27, 7-14. Retrieved from

https://www.nursingeconomics.net/

Kealey, B., & Howie, A. (2013, November). ICD-10 is coming: An update on medical diagnosis

and inpatient procedure coding. Minnesota Medicine, 48-50. Retrieved from

www.minnesotamedicine.com/_](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4b8d9c7d-55a0-4705-8f5f-53f25e3bcf63-151104213538-lva1-app6891/85/FinalPortfolioDraft-September-1-2015-51-320.jpg)

![Larkin, H. (2012, November). Focus on the c-suite: listener-in-chief. Hospitals & Health

Networks, 32-36. Retrieved from www.hhnmag.com

McDonald, K. M., Matesic, B., Contopoulos-loannidis, D. G., Lonhart, J., & Schmidt, E. (2013).

Patient safety strategies targets at diagnostic errors [Supplemental material]. Annals of

Internal Medicine, 158(5), 381-389. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303051-00004

Michalak, J. (2011). The quality of patients’ data in medical documentation and statistical forms.

Studies in logic, grammar and rhetoric, 25(38), 143–158. Retrieved from

http://journals.indexcopernicus.com

Nichols, J. C. (2014, November 15). ICD-10 and clinical documentation [Video file]. Retrieved

from http://www.medscape.org/

Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2012). Nursing Research Generating and assessing evidence for

nursing practice (9th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Lippincott Williams &

Wilkins.

Quan, H., Eastwood, C., Cunningham, C., Liu, M., Flemons, W., De Coster, C., & Ghali, W. A.

(2013). Validity of AHRQ patient safety indicators derived from ICD-10 hospital

discharge abstract data (chart review study). British Medical Journal Open, 3, 1-7. doi:

10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003716

Richardson, A., & Storr, J. (2010). Patient safety: a literature review on the impact of nursing

empowerment, leadership and collaboration. International Nursing Review, 57, 12-21.

Retrieved from http://www.icn.ch/

Riva, J. J., Malik, K. M., Burnie, S. J., Endicott, A. R., & Busse, J. W. (2012). What is your

research question? An introduction to the PICOT format for clinicians. Journal of the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4b8d9c7d-55a0-4705-8f5f-53f25e3bcf63-151104213538-lva1-app6891/85/FinalPortfolioDraft-September-1-2015-52-320.jpg)

![55

Planned Change in a Department

To Err is Human: Building a safer health system reports that medication errors are

occurring frequently, even with technology in place to make medication administration safer

(Committee on quality of health care in America [IOM Committee], 1999). Nursing leaders

have a responsibility to lead changes within a department or across departments. The purpose of

this paper is to review the issue in a department, describe how to change practice to meet facility

mission, vision, values, and professional standards. Describe how to facilitate the change using a

change model, and the stakeholders who should be involved.

Problem in the Department

The patient had stopped the nurse before the chemotherapy was administered, to let the

nurse know that this was not the chemotherapy she should receive. A review was done based on

this episode for the number of chemotherapy errors in the last six months. Chemotherapy

administration involves intricate protocols with high-risk medications. The size of the error can

determine how harmful it could be to the patient. Even a small error could cause renal damage

(Vioral & Kennihan, 2012). The risk management department completed the review, and they

found an average of 30 chemotherapy errors per month. The errors were primarily wrong drug

and wrong dose.

Specific Change to Practice

The policy at the hospital stated that two nurses had to verify the “Five Rights” of

medication administration at the patient bedside. The American Society of Clinical Oncology

(ASCO) and Oncology Nurse Society (ONS) standards state “A practitioner who is

administering the chemotherapy confirms with the patient his/her planned treatment prior to each](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4b8d9c7d-55a0-4705-8f5f-53f25e3bcf63-151104213538-lva1-app6891/85/FinalPortfolioDraft-September-1-2015-55-320.jpg)

![References

Committee on quality of health care in America. (1999). To err is human: Building a safer health

system [Issue brief]. Retrieved from Institute of Medicine website: http://www.iom.edu

Cancer Treatment Centers of America website. (n.d.). http://www.cancercenter.com

Code of Ethics for Nurses. (2010). Retrieved September 21, 2014, from

http://www.nursingworld.org

Marquis, B. I., & Huston, C. J. (2012). Leadership Roles and Management Functions in Nursing

(7th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Neuss, M. N., Polovich, M., McNiff, K., Espir, P., Gilmore, T. R., LeFebvre, K. B., ... Jacobson,

J. O. (2013, March). 2013 Updated American Society of Clinical Oncology/Oncology

Nursing Society Chemotherapy Administration Safety Standards including standards for

the safe administration and management of oral chemotherapy. JOURNAL OF

ONCOLOGY PRACTICE, 9(2s), 5s-13s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.000874

Vioral, A. N., & Kennihan, H. K. (2012, December). Implementation of the American Society of

Clinical Oncology and Oncology Nursing Society Chemotherapy Safety Standards: A

multidisciplinary approach. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16, E226-E230. doi:

10.1188/12.CJON.E226-E230](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4b8d9c7d-55a0-4705-8f5f-53f25e3bcf63-151104213538-lva1-app6891/85/FinalPortfolioDraft-September-1-2015-60-320.jpg)

![References

American Nurses Association. (2008). Nursing informatics : scope and standards of practice.

Silver Spring, Md.: American Nurses Association.

Aveyard, H. (2007). Doing a literature review in health and social care: A practical guide:

McGraw-Hill International [UK] Limited.

Berner, E. S. (2008). Ethical and legal issues in the use of health information technology to

improve patient safety. HEC Forum: An Interdisciplinary Journal On Hospitals' Ethical

And Legal Issues, 20(3), 243-258. doi: 10.1007/s10730-008-9074-5

Bonkowski, J., Carnes, C., Melucci, J., Mirtallo, J., Prier, B., Reichert, E., . . . Weber, R. (2013).

Effect of Barcode-assisted Medication Administration on Emergency Department

Medication Errors. Academic Emergency Medicine, 20(8), 801-806. doi:

10.1111/acem.12189

Cork, R. D., Detmer, W. M., & Friedman, C. P. (1998). Development and Initial Validation of an

Instrument to Measure Physicians' Use of, Knowledge about, and Attitudes Toward

Computers (Vol. 5).

Frame the boundaries for an evaluation. (2013). Retrieved July 20, 2015, from

http://betterevaluation.org/plan/engage_frame/criteria_and_standards

Friedman, C. P., & Wyatt, J. C. (2006a). Developing and improving measurement methods

Evaluation Methods in Biomedical Informatics (pp. 145-187). New York, NY: Springer,

NY.

Friedman, C. P., & Wyatt, J. C. (2006b). Evaluation as a field Evaluation Methods in Biomedical

Informatic (pp. 21-47). New York, NY: Springer New York.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4b8d9c7d-55a0-4705-8f5f-53f25e3bcf63-151104213538-lva1-app6891/85/FinalPortfolioDraft-September-1-2015-154-320.jpg)