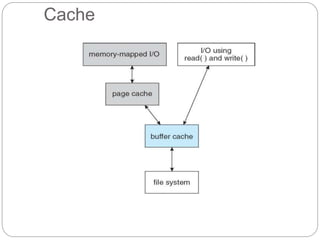

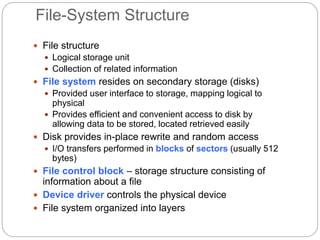

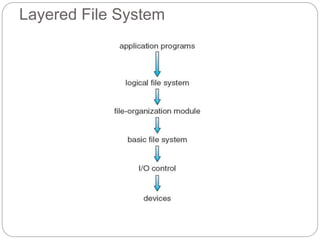

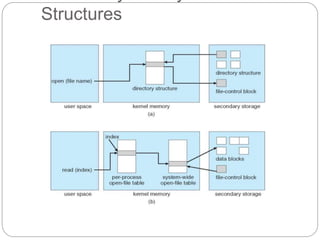

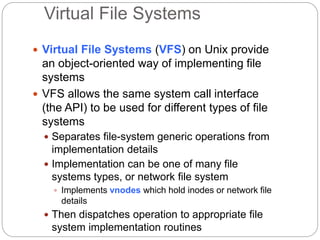

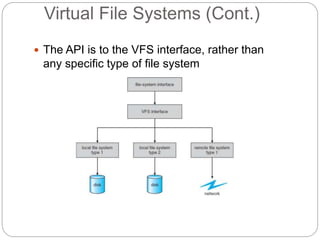

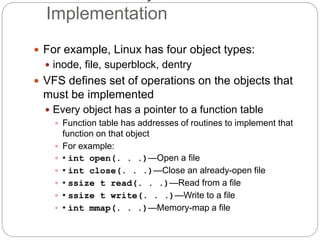

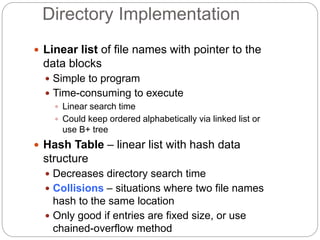

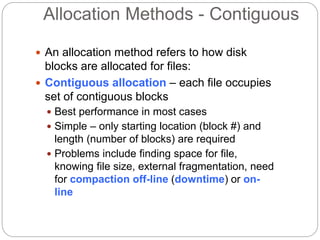

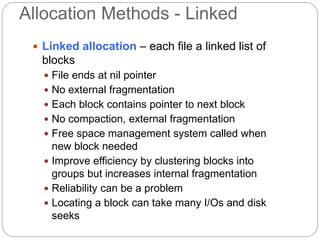

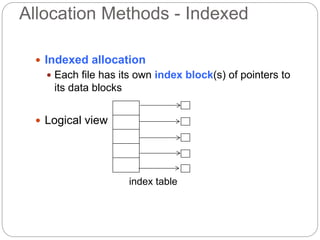

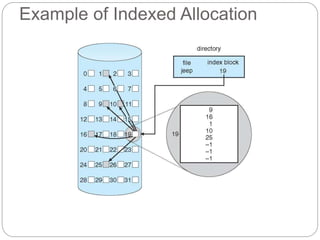

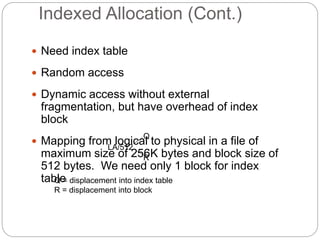

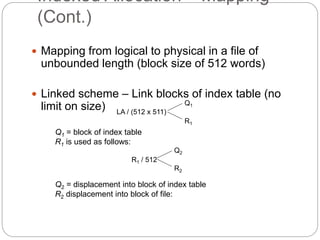

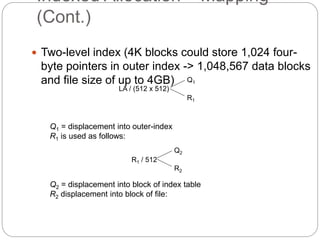

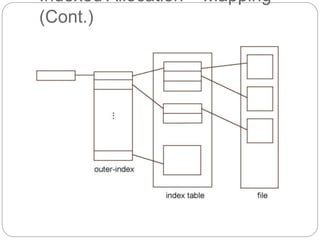

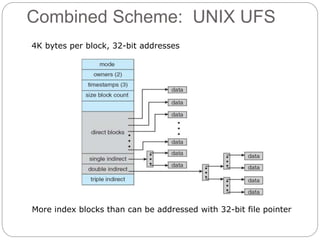

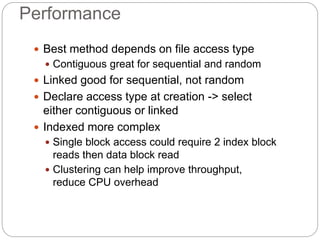

The document provides an extensive overview of file system implementation, including its structure, directory management, and various allocation methods such as contiguous, linked, and indexed allocation. It discusses efficiency, performance objectives, and free-space management techniques within both local and remote file systems, alongside the layered architecture that aids in complexity reduction. Additionally, it examines virtual file systems and highlights the evolution of multiple file system types across operating systems.

![Free-Space Management

File system maintains free-space list to track

available blocks/clusters

(Using term “block” for simplicity)

Bit vector or bit map (n blocks)

…

0 1 2 n-1

bit[i] =

1 block[i] free

0 block[i] occupied

Block number calculation

(number of bits per word) *

(number of 0-value words) +

offset of first 1 bit

CPUs have instructions to return offset within word of first “1” bit](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/filemanagementpart2osnotes-221106083052-203da80f/85/file-management_part2_os_notes-ppt-35-320.jpg)