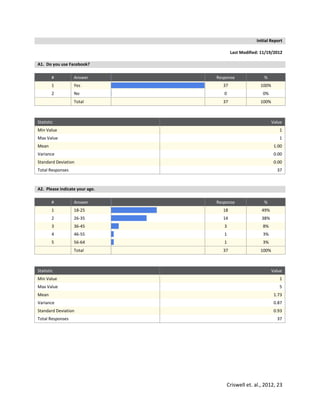

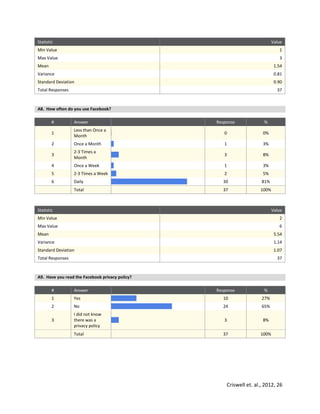

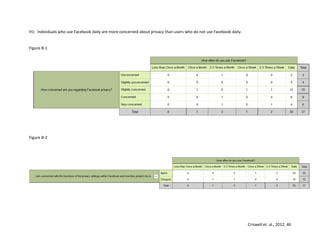

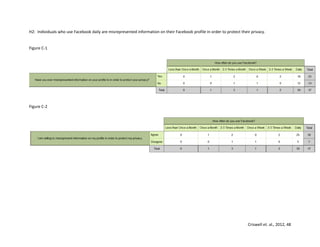

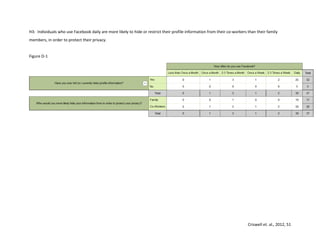

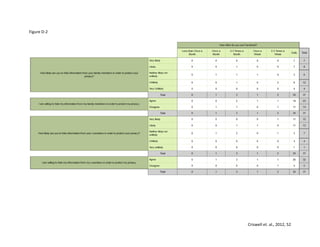

This study examines how Facebook users manage their privacy and personal information disclosure based on Communication Privacy Management theory. A survey and content analysis were conducted to understand the relationship between perceptions of Facebook privacy and efforts to stay updated on privacy settings. The introduction provides background on social networking sites and how they have changed communication. Hypotheses are presented that Facebook users who use the site daily will be more concerned about privacy and more likely to hide or restrict information from coworkers than family.