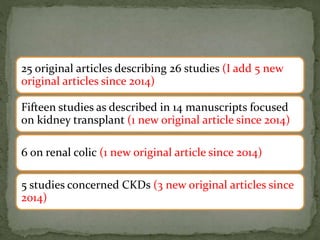

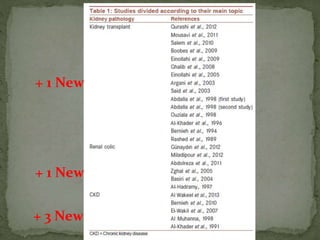

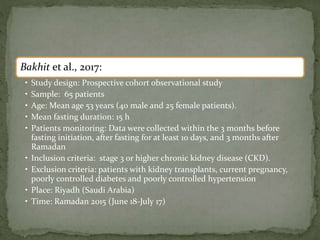

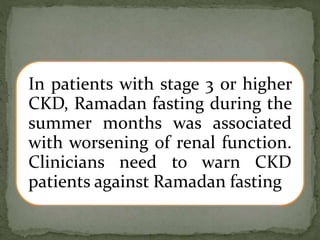

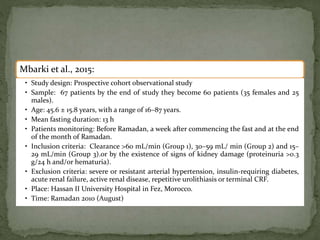

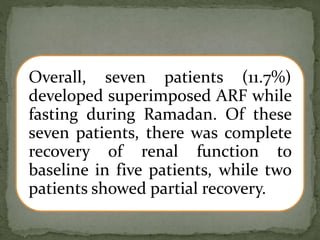

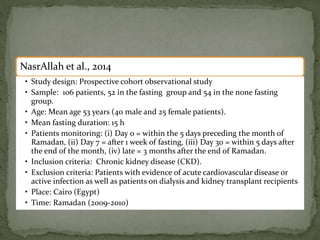

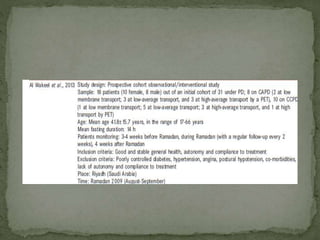

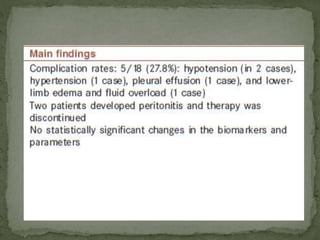

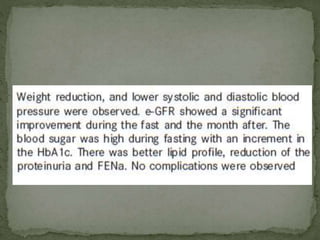

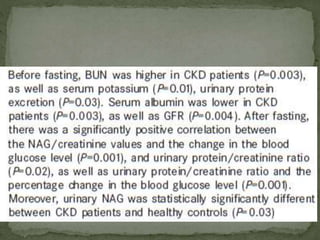

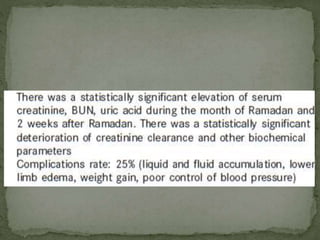

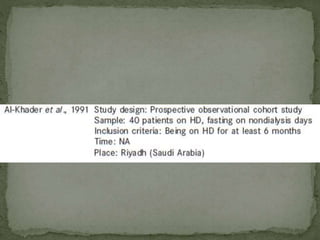

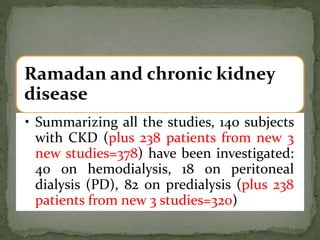

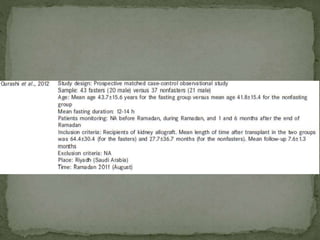

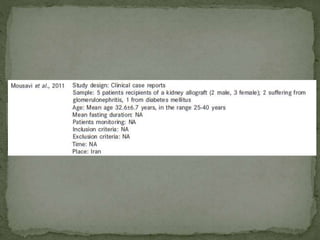

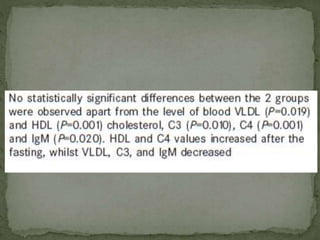

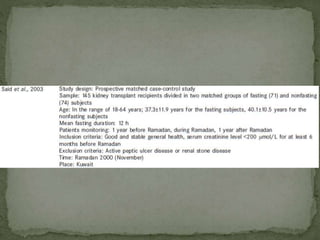

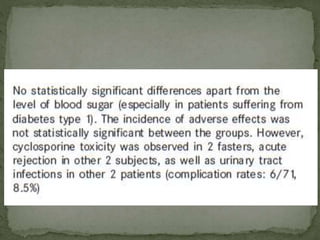

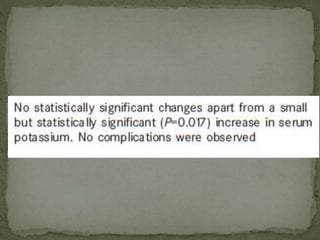

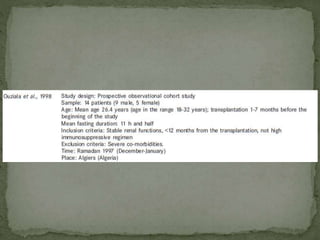

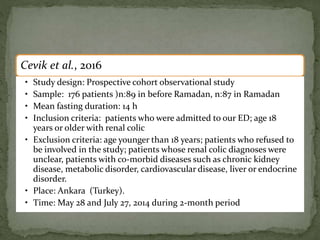

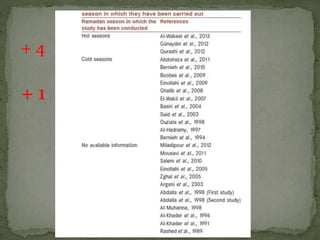

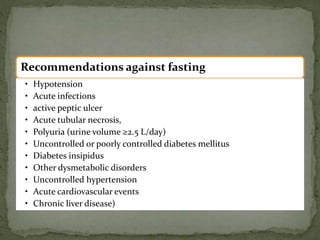

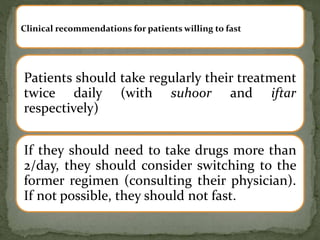

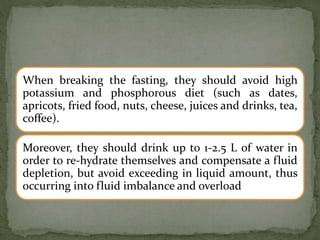

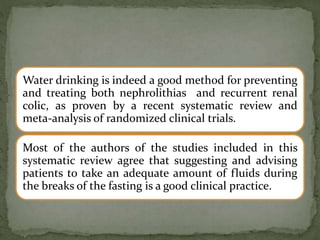

Ramadan fasting and chronic kidney disease: A systematic review summarizes 25 original studies (now totaling 31 studies) investigating the relationship between Ramadan fasting and chronic kidney disease. The studies analyzed a total of 1,262 subjects with CKD who fasted during Ramadan (now totaling 1,638 including subjects from 3 new studies). Most studies found that fasting did not significantly impact renal function or biochemical parameters, with any changes fully reversible after Ramadan. However, two new studies found worsening renal function or cardiovascular events in patients with advanced CKD or risk factors who fasted. Fasting may be allowed for most CKD patients with precautions like medication adjustments and monitoring, but is not recommended for