This document provides an overview of a facilitator's toolkit for training. It discusses:

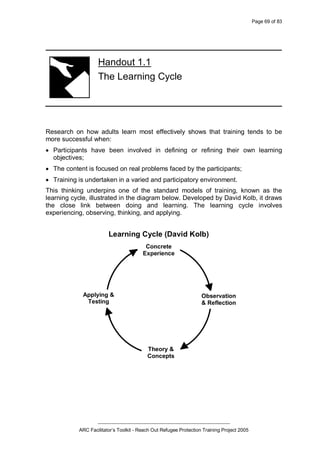

1. Principles of adult learning, including Kolb's learning cycle of concrete experience, observation and reflection, formation of abstract concepts, and testing in new situations.

2. Different approaches to training, such as on-the-job training, in-house experiences, and in-house or external courses.

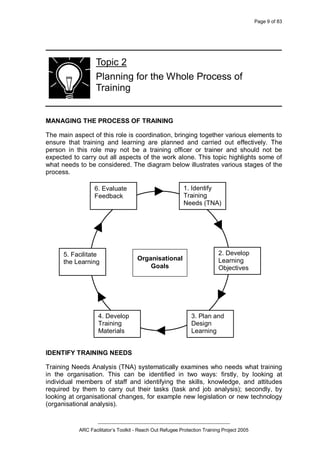

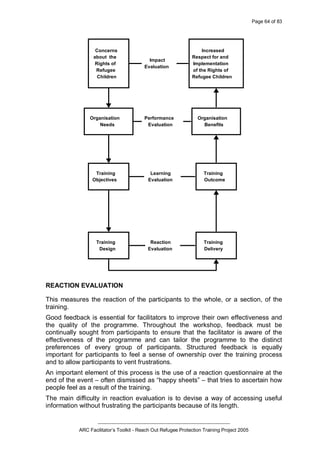

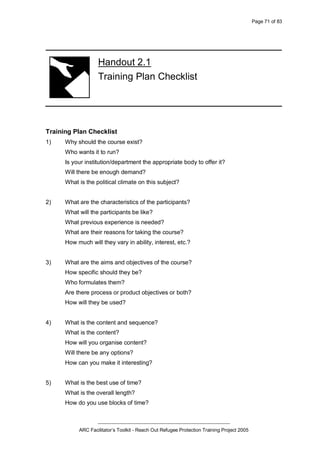

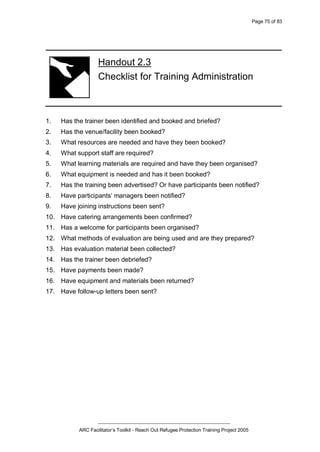

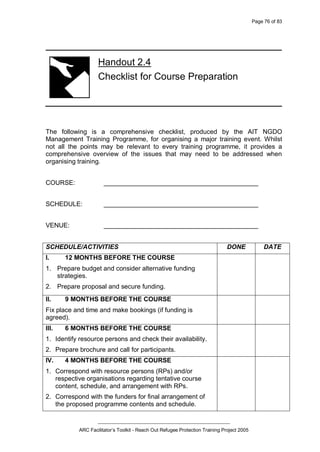

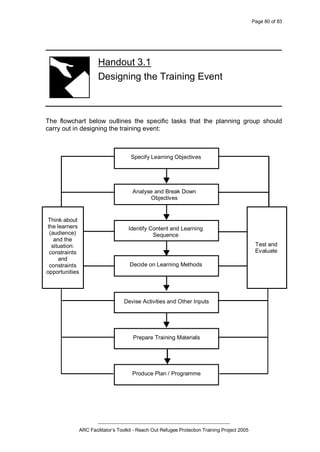

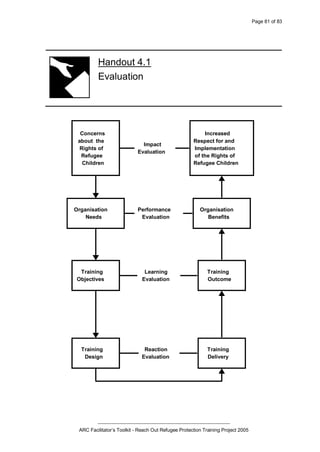

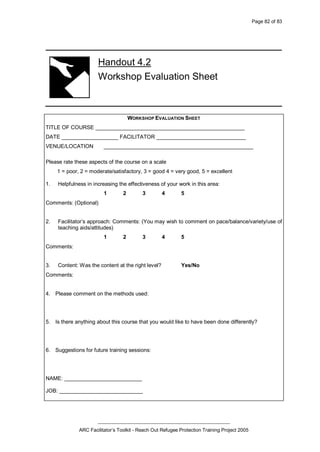

3. Key topics covered in the toolkit include planning training, facilitation techniques, case studies, feedback and evaluation.