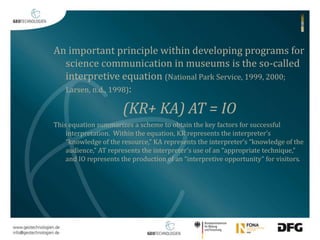

This document discusses how museums can effectively communicate earth science topics to visitors. It emphasizes that the goal of interpretation should be to provoke curiosity, not just convey facts. Successful interpretation requires knowledge of both the resource and the audience. The document also stresses that scientists should collaborate with museums, which have expertise in interpretation, exhibition design, and audience engagement. Accompanying text is important but can undermine exhibits if it uses too much scientific jargon or information. Overall, earth scientists and museums should work together to spark visitors' natural curiosity about the planet.

![Wells, Butler, and Koke (2013) quoted Sir Ken

Robinson that

“rather than anesthetizing learners using the

traditional factory model [of education] we should

be waking them up by stimulating their

imaginations and creativity”.

Ergo, taking science into museums should not have

strict learning as a goal; instead, it should focus on

provoking critical thinking and curiosity.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/experienceplanetearth-geofrankfurt2014-2-140925082753-phpapp01/85/Experience-planet-earth-10-320.jpg)

![References

Ward, C. W., & Wilkinson, A. E. (2006). Conducting meaningful interpretation: A field guide for success.

Golden, CO, USA: Fulcrum Publishing.

Hudec, H. (2004). Evaluation: A critical step in creating effective museum exhibits. (Unpublished thesis).

University of Chicago. Retrieved from

http://mps.uchicago.edu/docs/2005/articles/hudec_thesis_short.pdf

Renn, O. (1986). Akzeptanzforschung: Technik in der gesellschaftlichen Auseinandersetzung. Chemie in

unserer Zeit. 20. Jhrg. Nr.2. Weinheim, Germany: VCH VerlagsgesellschaftmbH (p 44–52).

Schiele, B, Claessens, M., Shi, S. (2012). Science Communication in the World, Hamburg, Germany: Springer

(pp 125–137)

Wells, M. D., Butler, B., & Koke, J. (2013). Interpretive planning for museums. Walnut Creek, CA, USA:

LeftCoast Press.

National Park Service. (1999). All about the program. Interpretive Development Program Homepage [On-line].

Retrieved from http://www.nps.gov/idp/interp/

National Park Service. (2000). Module 101: How interpretation works: The interpretive equation. Interpretive

Development Program Homepage. [On-line]. Retrieved from

http://www.nps.gov/idp/interp/101/howitworks.htm

Larsen, D. L. (1998). Observation for “Quest” meeting. (Unpublished manuscript).

Leyland, E. (2011). Interpretive Text Panels. Retrieved from

http://eric-leyland.blogspot.de/2011/08/interpretive-text-panels.html

Bitgood, S. (2000). The role of attention in designing effective interpretive labels. Journal of Interpretation

Research, 5(2), 31–45.

Carroll, B., Huntwork, D., & St. John M. (2005). Traveling exhibits at museums of science (TEAMS). A

Summative Evaluation Report, Inverness Research Associates. Retrieved from http://www.inverness-research.

org/reports/2005-04-teams/2005-04-Rpt-Teams-summative_eval.pdf](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/experienceplanetearth-geofrankfurt2014-2-140925082753-phpapp01/85/Experience-planet-earth-17-320.jpg)