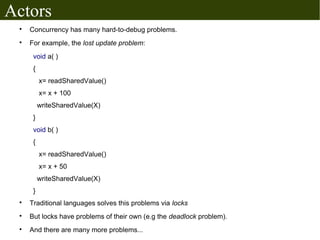

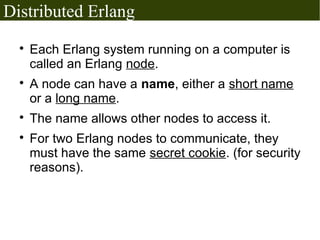

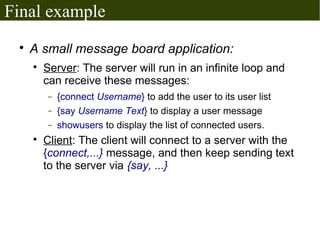

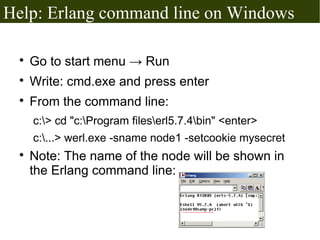

The document discusses Erlang's boolean values, operators, control structures (if and case expressions), anonymous functions, higher-order functions, and actor-based concurrency model. It explains the lightweight processes in Erlang, message sending and reception, and the creation of distributed systems through nodes with shared cookies for communication. Additionally, it covers practical examples such as an interactive counter and a message board application, alongside further topics on error handling and various applications.

![Higher order functions

These are functions that take functions as

parameters or return functions as results.

Some built-in HOFs:

lists:any(testFunc, list)

Even = fun (X)

(X rem 2) == 0

end.

lists:any(Even,[1, 2 ,3, 4]).

− This will test if any member of the given list even (which

is true).

Also lists:all, lists:foldl, lists:foldr, lists:mapfoldl

And many other functions!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-session2-110831184403-phpapp01/85/Erlang-session2-7-320.jpg)

![Creating new processes

spawn(Module, Function, [ arg1, arg2...] )

Creates a new process which starts by running

function with the specified arguments.

The caller of spawn resumes working normally and

doesn't wait for the process to end.

Returns a data of type Process ID (PID), which is

used to access the process.

There exist a number of other spawn(...) BIFs, for

example spawn/4 for spawning a process at

another node.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-session2-110831184403-phpapp01/85/Erlang-session2-13-320.jpg)

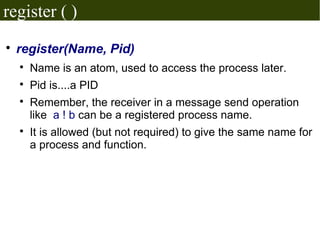

![receiving messages

receive

Pattern1 [when GuardSeq1] ->

Body1;

...

PatternN [when GuardSeqN] ->

BodyN

end

Receives messages sent with `!` to the current process's

mailbox.

The [when guard_sequence] part is optional.

When receiving a message, it is matched with each of the

patterns (and guard sequences). When the first match

happens, it's body is executed.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-session2-110831184403-phpapp01/85/Erlang-session2-15-320.jpg)

![Example actor: Hi, Bye!

-module(hi_bye).

-export(run/0).

run ( )->

receive

hi →

io:format("bye!~n", [ ]),

run( ),

end.

after compiling the module:

erlang> PID = spawn(hi_bye, run, [ ]).

erlang> PID ! hi.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-session2-110831184403-phpapp01/85/Erlang-session2-18-320.jpg)

![More stuff in Erlang...

Error handling using workers, supervisors

and supervision trees.

Bit syntax and bit operations

The built-in Mnesia database (and others)

List comprehensions:

L = [ {X, Y} || X<- [1,2,3,4], Y <-[1,2,3,4], X+Y==5]

L = [ {1, 4}, {2, 3}, {3, 2}, {4,1} ]

Web applications, GUI applications,

Networking, OpenGL, other databases...

....etc](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-session2-110831184403-phpapp01/85/Erlang-session2-30-320.jpg)