The document provides an overview and introduction to the ePMbook, which is an ebook about project management. It discusses that the ePMbook examines project management issues and approaches in different situations. It also outlines some of the main types of content covered in the ePMbook, including examining the day-to-day activities of a project manager and other conceptual topics. It notes that the ePMbook is intended to be read online and allows nonlinear navigation of the content.

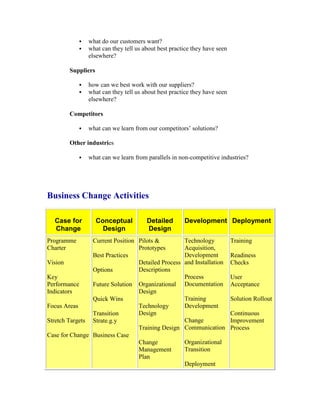

![Activity, process, deliverable, outcome, or milestone-focused?

Here is an esoteric debate for Project Managers to discuss over beers in the evening. The

question is - how do we define the 'things' in the plan - what are they? Let's take a look at

several philosophies: activity, process, deliverable, outcome, and milestone.

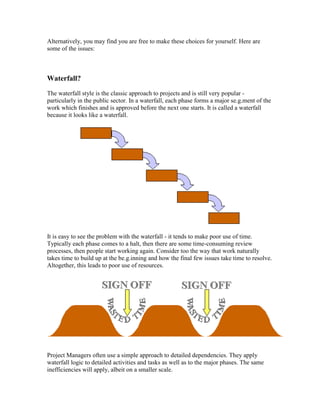

The classic and common understanding is that a plan tells you what things to do. It

describes the various activities that are required. These would typically be broken down

and structured into cate.g.ories for ease of understanding. This is a basic concept in

Project Management - the Work Breakdown Structure (WBS).

Here is a very typical example structure of an activity-focused plan:

Logical Structure Example

Phase 1 Phase 1 - Define the Project

Activity 1 Define Project Scope

Task A Define Scope

Task B Agree Scope

Activity 2 Prepare Benefit Case

Task C Construct Benefit Case

Task D Agree Benefit Case

Note that because we are talking about activities and tasks we are using verbs - action

expressions. In fact the typical construction is in the form verb + noun ie "do the thing".

A variation of this is to use a process focus for the structure of the plan, but, probably,

leave the low-level tasks and deliverables at the same level. Process focus is following

the evolution in thinking that occurred in analysing business processes - except here

applied to the processes of a project. The intention is to tell the story of each process

within the project rather than present it in a disjointed way divided up into phases. For

example, one section of the plan would describe the story of testing. It would start with

the early definition of the project's approach to testing, through the detailed planning,

testing preparation, conducting tests and gaining business acceptance. As well as telling

the story in a way that is easier to understand, the process focus generally fits in with the

idea that projects can be organised into various workstreams, each dealing with a layer

of the overall business solution.

Here is a very typical example structure of a process-focused plan:

Logical Structure Example

Process 1 Delivering the project's objectives

Sub-process 1 Managing scope

Task A Define Scope

Task B [all further tasks dealing

with scope]

Sub-process 2 Delivering optimum benefit](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epmbook-240114051214-09980e1d/85/ePMBook-doc-33-320.jpg)

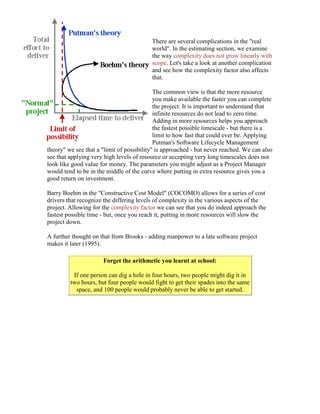

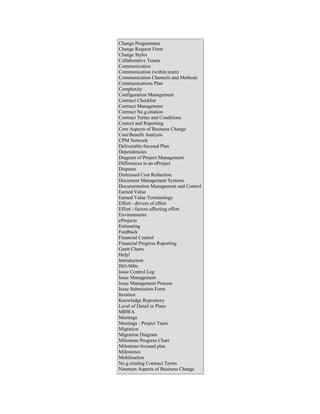

![Task C Construct Benefit Case

Task D [all further tasks dealing

with benefit]

The problem with a process focus is that it offends those Project Managers and Project

Sponsors who expect the plan to be organised in distinct stages. For example, the testing

process will start early in the project when the overall approach to testing is agreed; test

planning and preparation will occur in the middle; test execution and sign-off occur

towards the end. To place all these together might tell a good story - but it challenges the

common belief that project plans should be organised to show logical and/or time

progression. Within each process, such staging may be apparent, but in a single view it is

hard to present both the staging across processes and the story of each process.

You will probably hear some "rules of thumb" about how tasks should be defined, for

example, tasks should not be so long that progress cannot be tracked re.g.ularly or so

short that they are trivial - some people would suggest five days is a good length. The

problem here is that some very important things such as a "sign off" might be very short

in duration but vital to the good conduct of the project and others like "track progress"

might be very long tasks with no merit in sub-dividing them or measuring interim

progress.

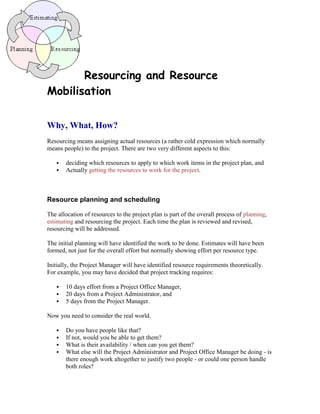

One common recommendation about defining tasks is that all tasks should have a

measurable output that clearly evidences the task is successfully completed and which

represents the main purpose of the task. For example, "Define Scope" might produce a

deliverable called "Scope Definition".

This leads some Project Managers to suggest that the entire approach might be better if

everyone focused not on doing tasks but on delivering the results - hence the project plan

could be expressed as deliverables and sub-deliverables.

For example, in a deliverable-focused plan the previous examples might look like this:

Logical Structure Example

Phase 1 Phase 1 - Project Definition

Major

Deliverable 1

Project Scope

Deliverable

A

Scope Definition

Deliverable

B

Scope sign off document

Major

Deliverable 2

Benefit Case

Deliverable

C

Benefit Case

Deliverable

D

Benefit Case sign off

document](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epmbook-240114051214-09980e1d/85/ePMBook-doc-34-320.jpg)