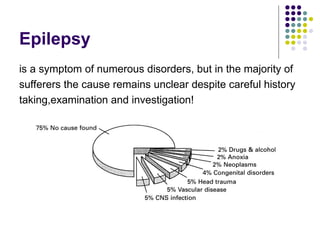

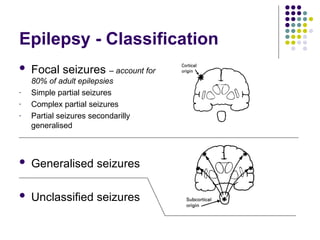

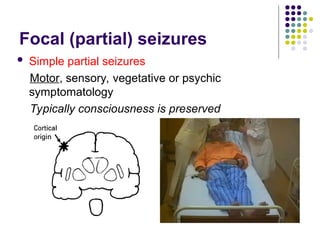

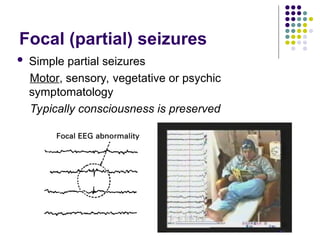

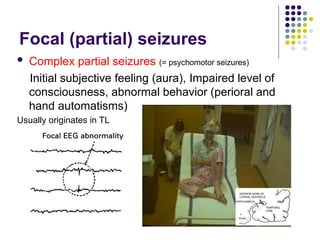

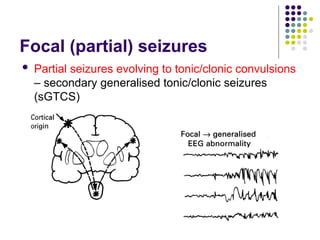

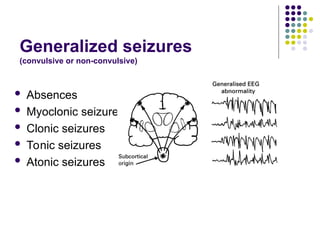

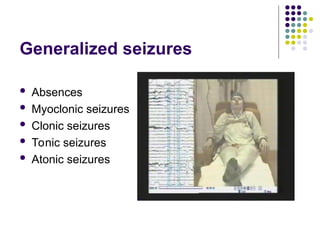

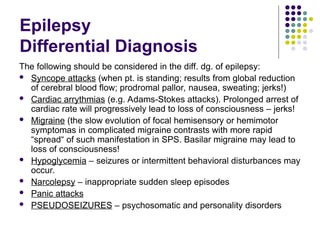

Epilepsy is a chronic neurological disorder characterized by recurrent seizures due to uncontrolled neuronal discharges in the central nervous system. It can occur at any age, with varying severity and types of seizures, classified into focal or generalized categories. Treatment often involves anticonvulsant medications, and in cases of drug-resistant epilepsy, surgical options may be considered.