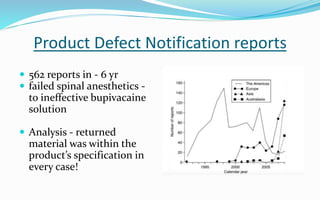

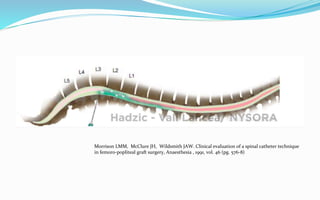

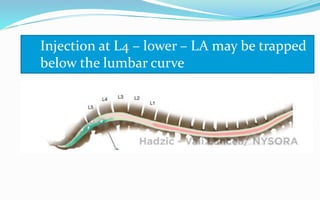

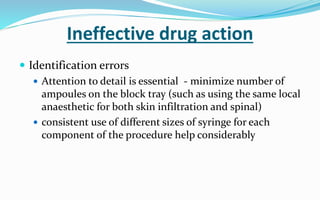

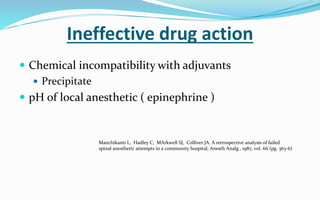

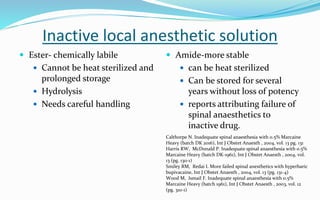

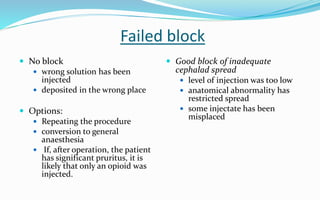

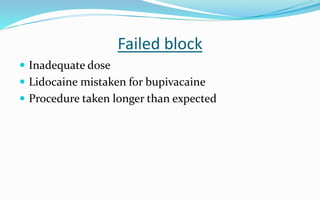

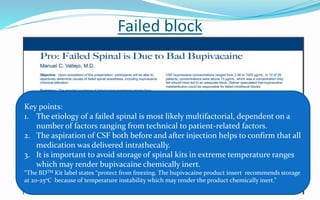

1. A failed spinal block can result from multiple technical and patient factors related to the lumbar puncture, injection, and spread of the local anesthetic.

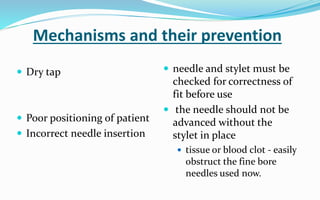

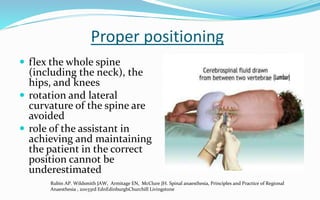

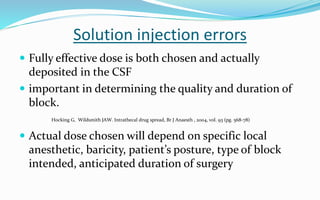

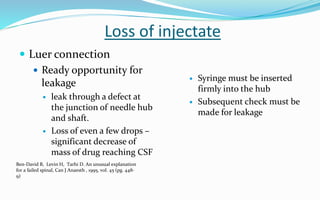

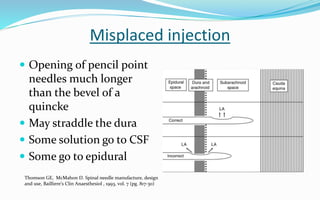

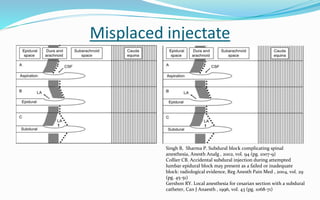

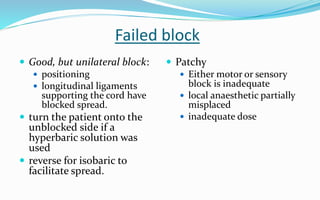

2. Proper patient positioning, meticulous attention to technique, and ensuring the full dose is delivered intrathecally are key to avoiding failure.

3. Factors like anatomical abnormalities, inadequate spread, misplaced injection, or inactive drug can all contribute to failure if not properly addressed. Careful consideration of each step is important for success.