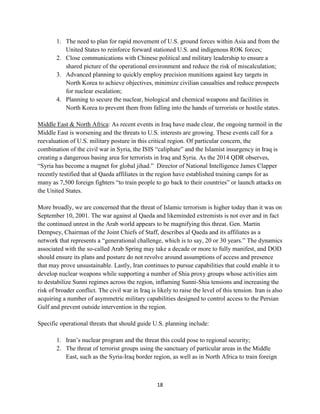

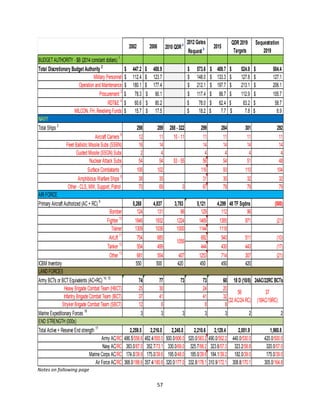

The document summarizes the key findings and recommendations from a report by the National Defense Panel on the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review. It finds that budget cuts from the Budget Control Act have significantly reduced readiness and capabilities. It recommends expanding the force sizing construct beyond two wars to account for increased threats around the world. It also recommends increasing funding to the levels proposed in the 2012 defense budget as the minimum needed. Specific forces like the Navy and Air Force need to be larger to meet requirements given the challenging threats. Innovation alone cannot substitute for needed funding increases.