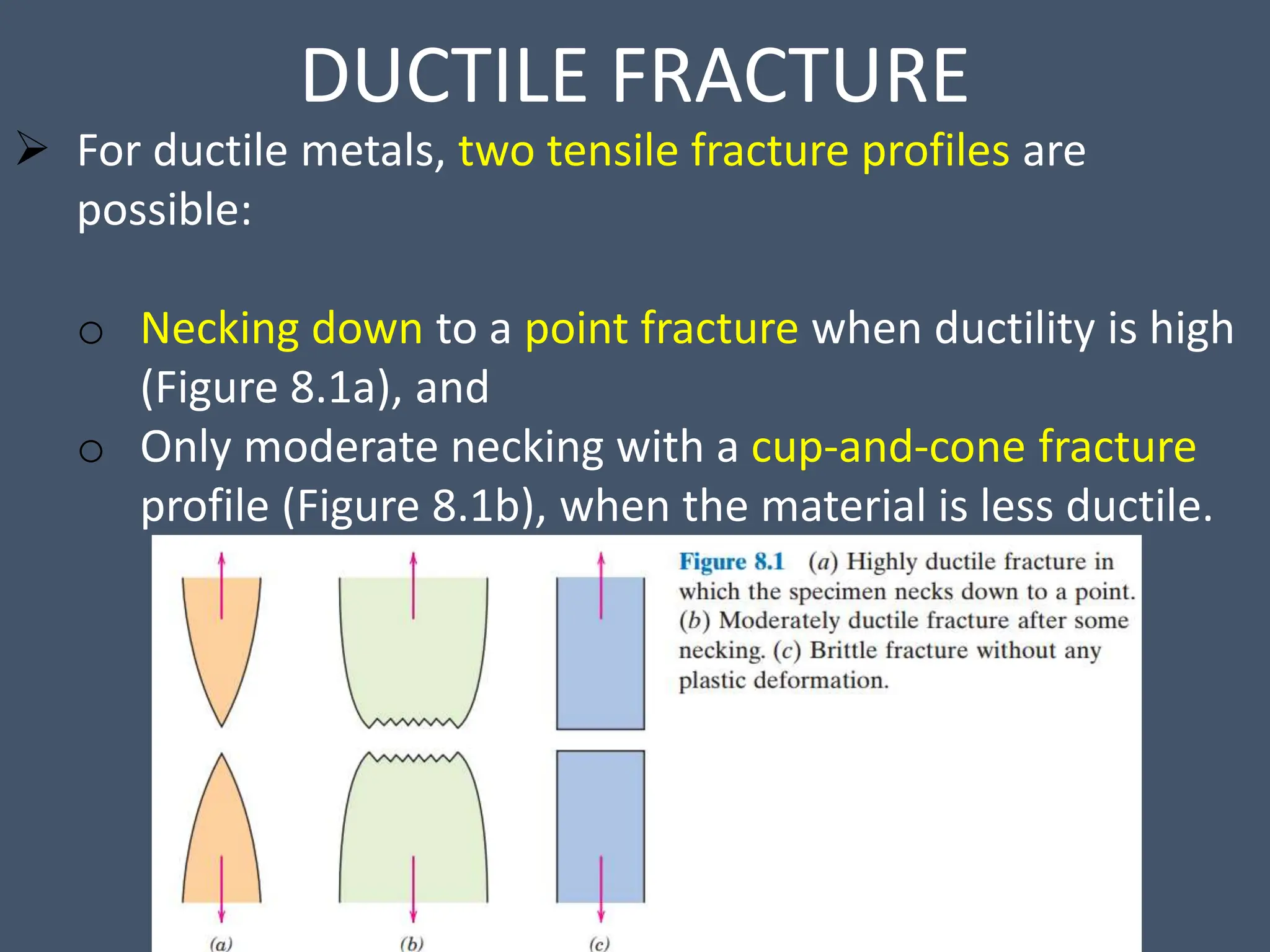

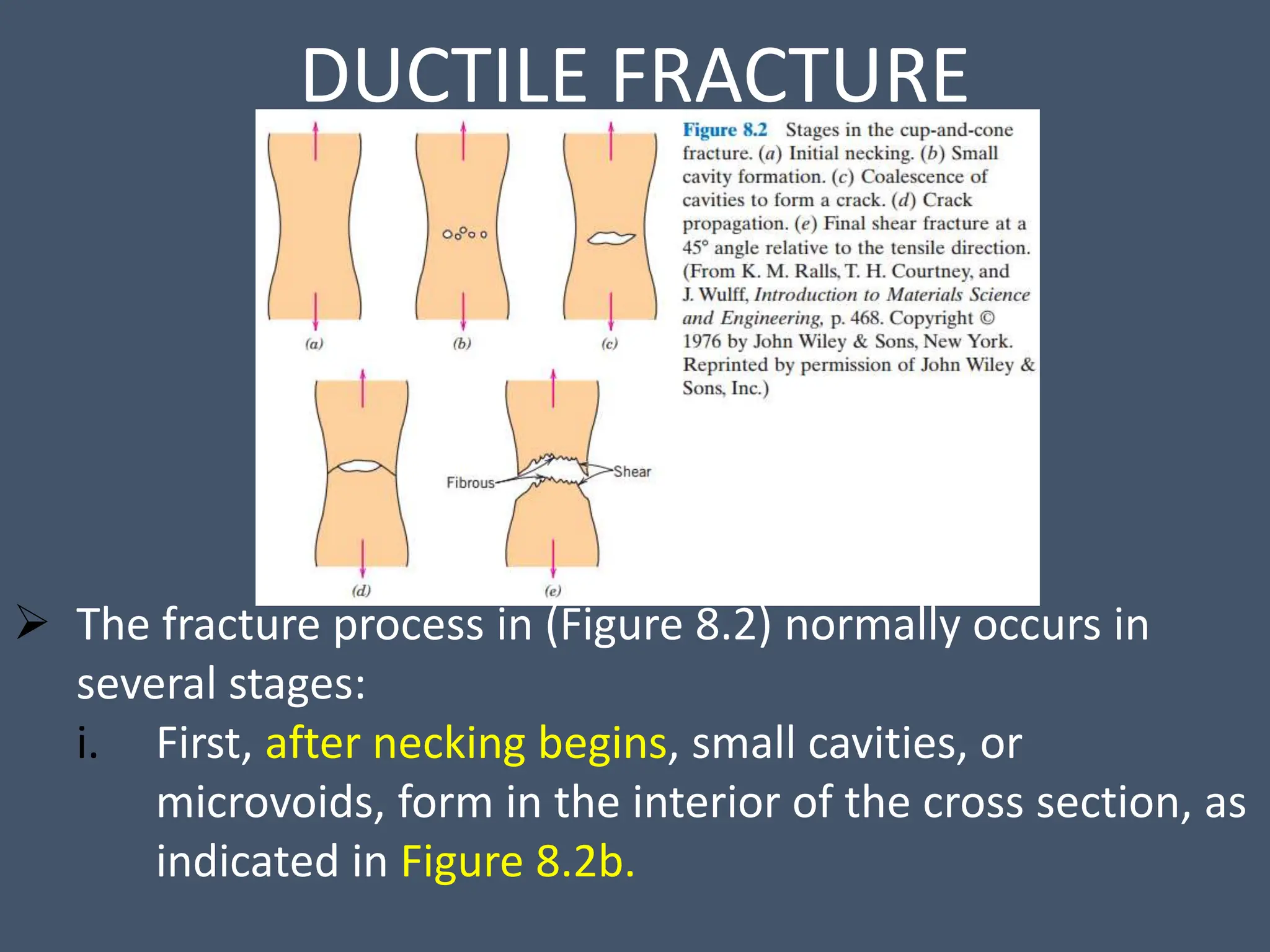

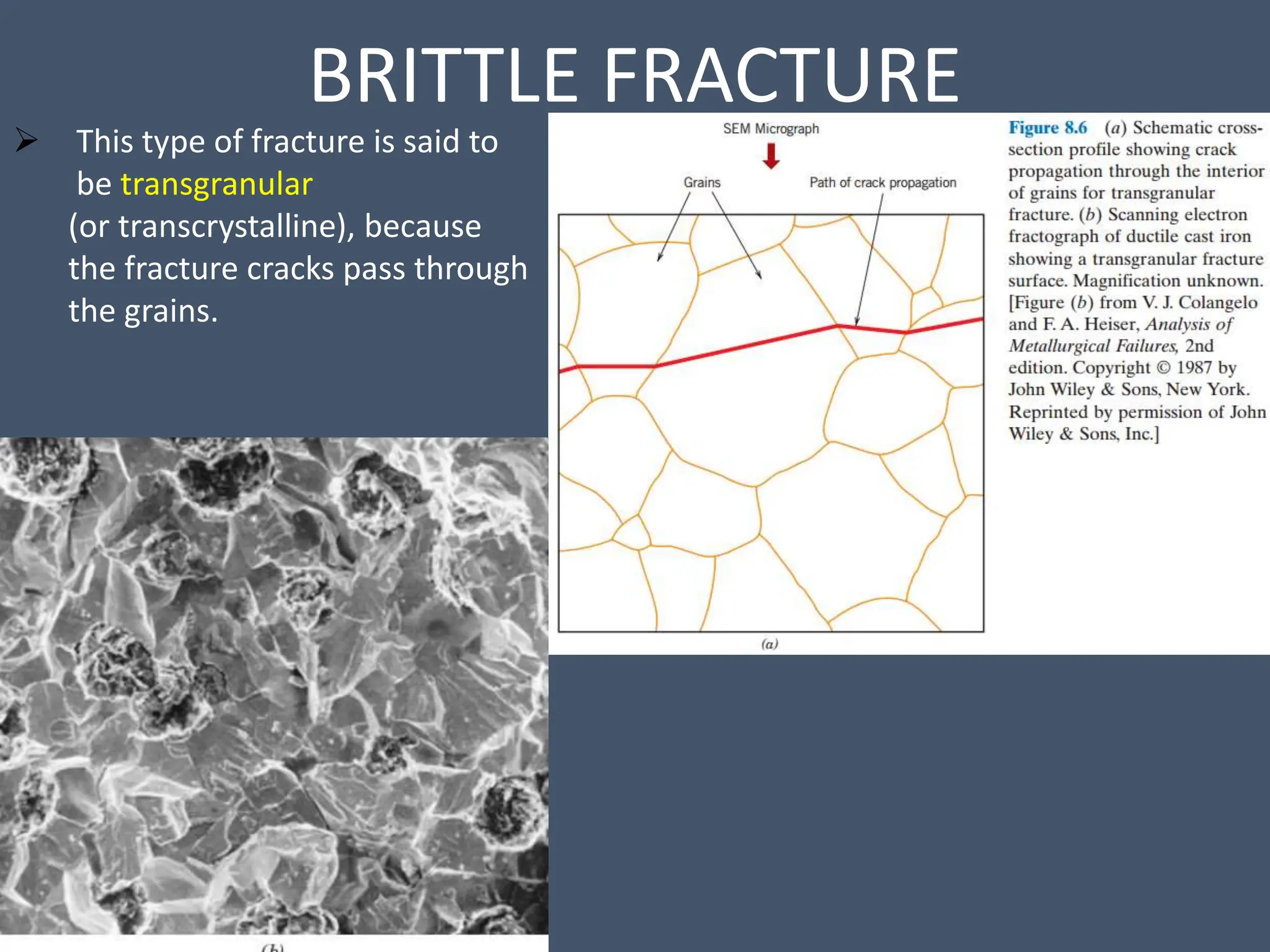

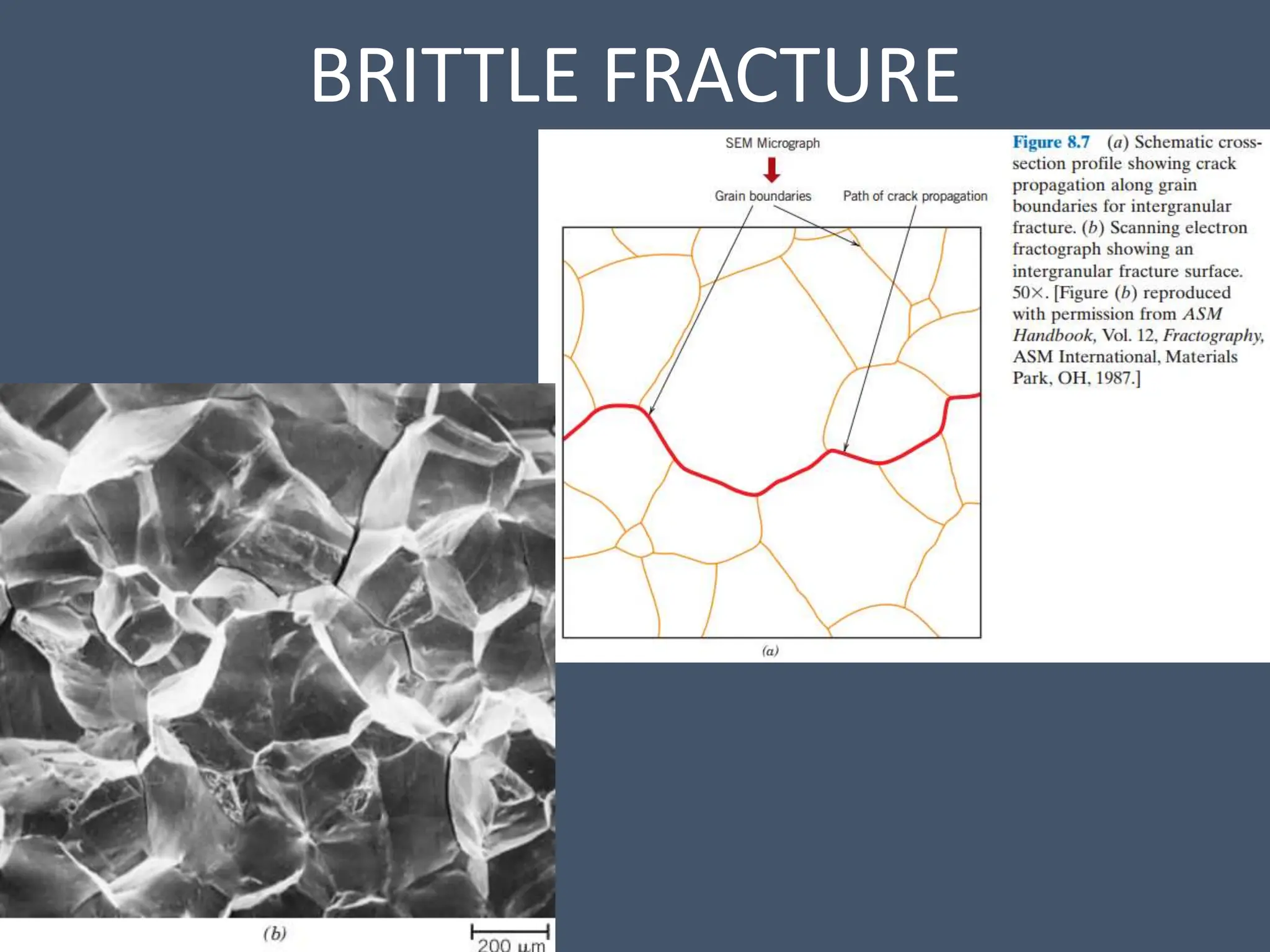

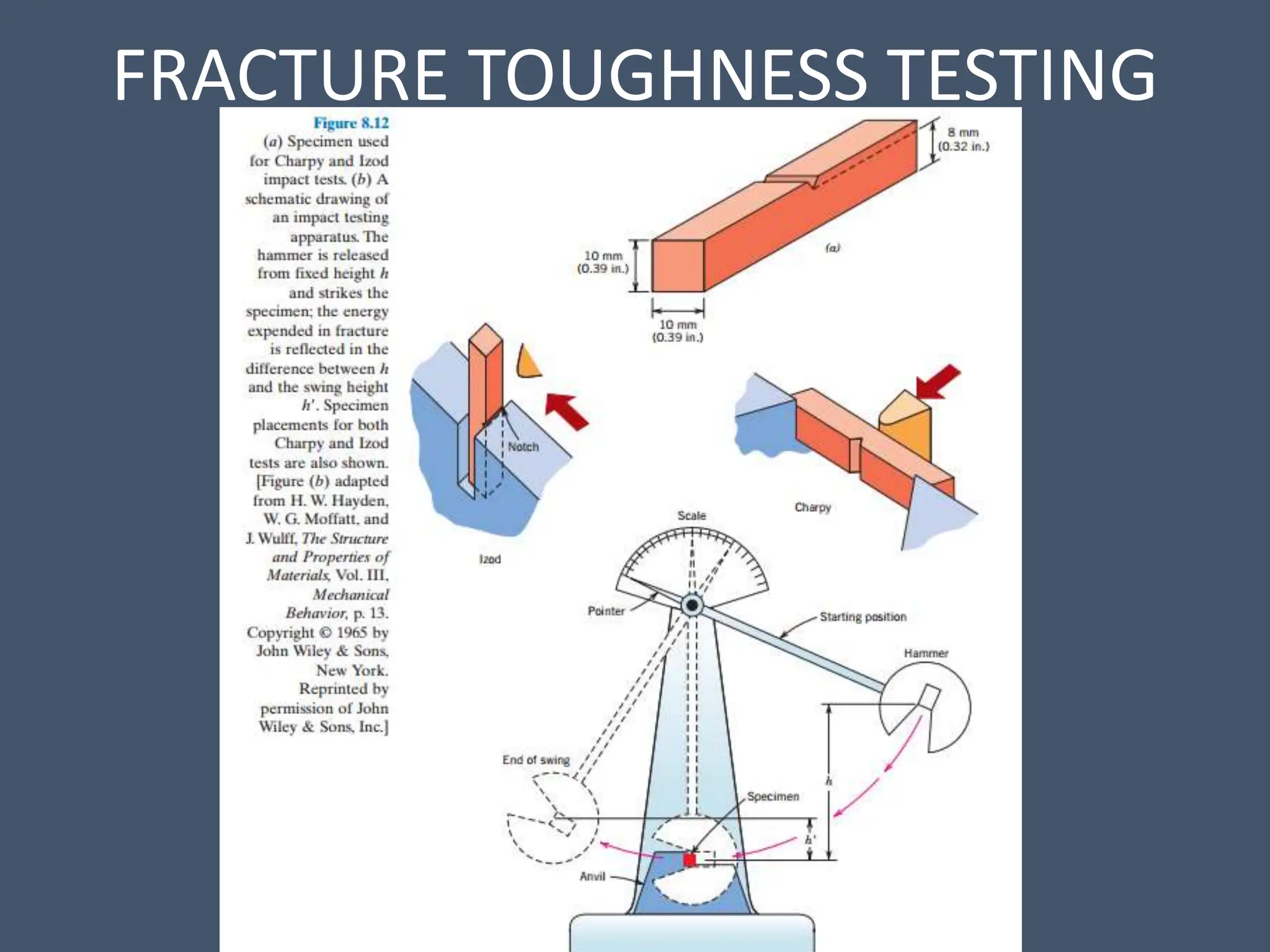

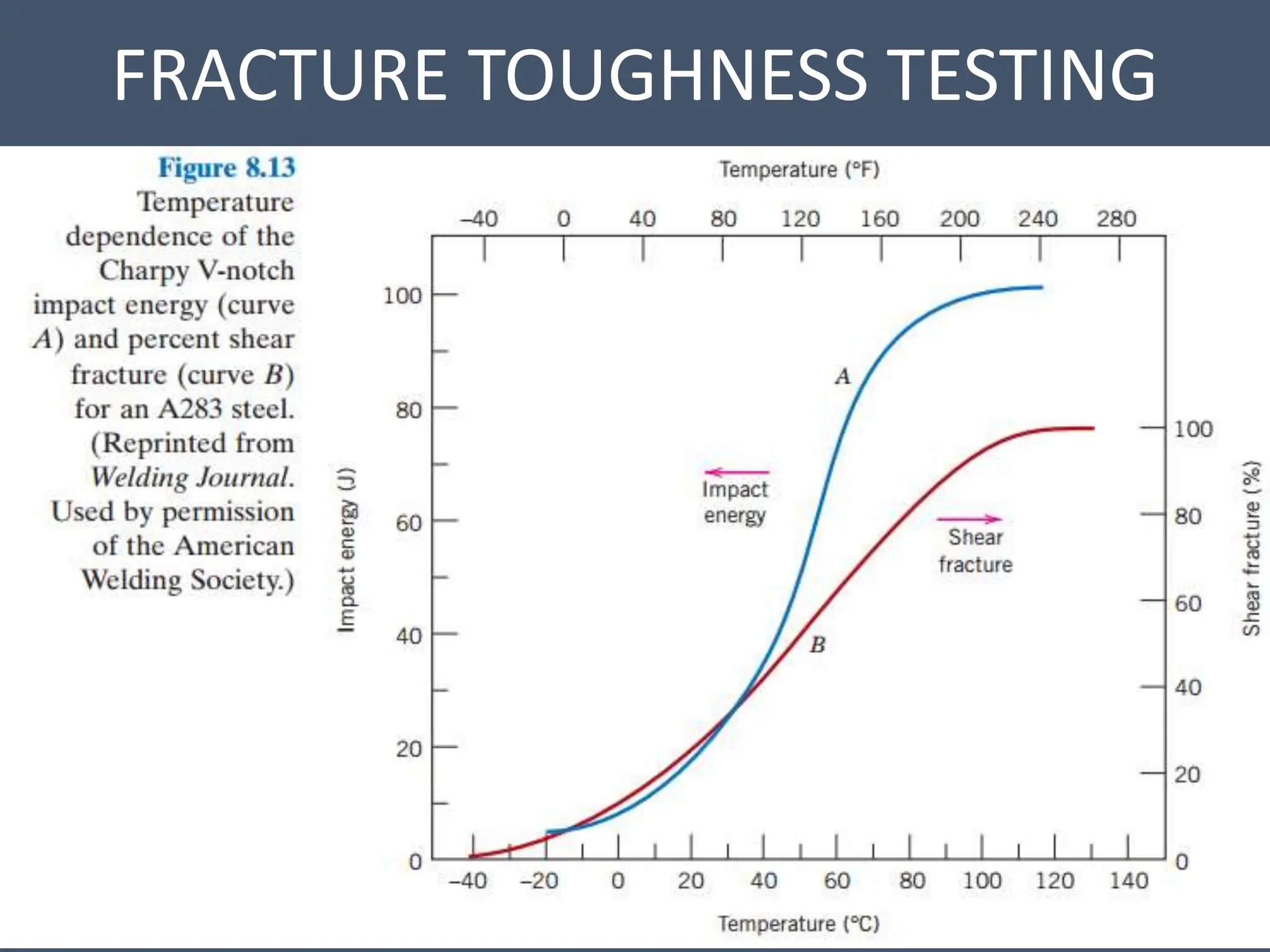

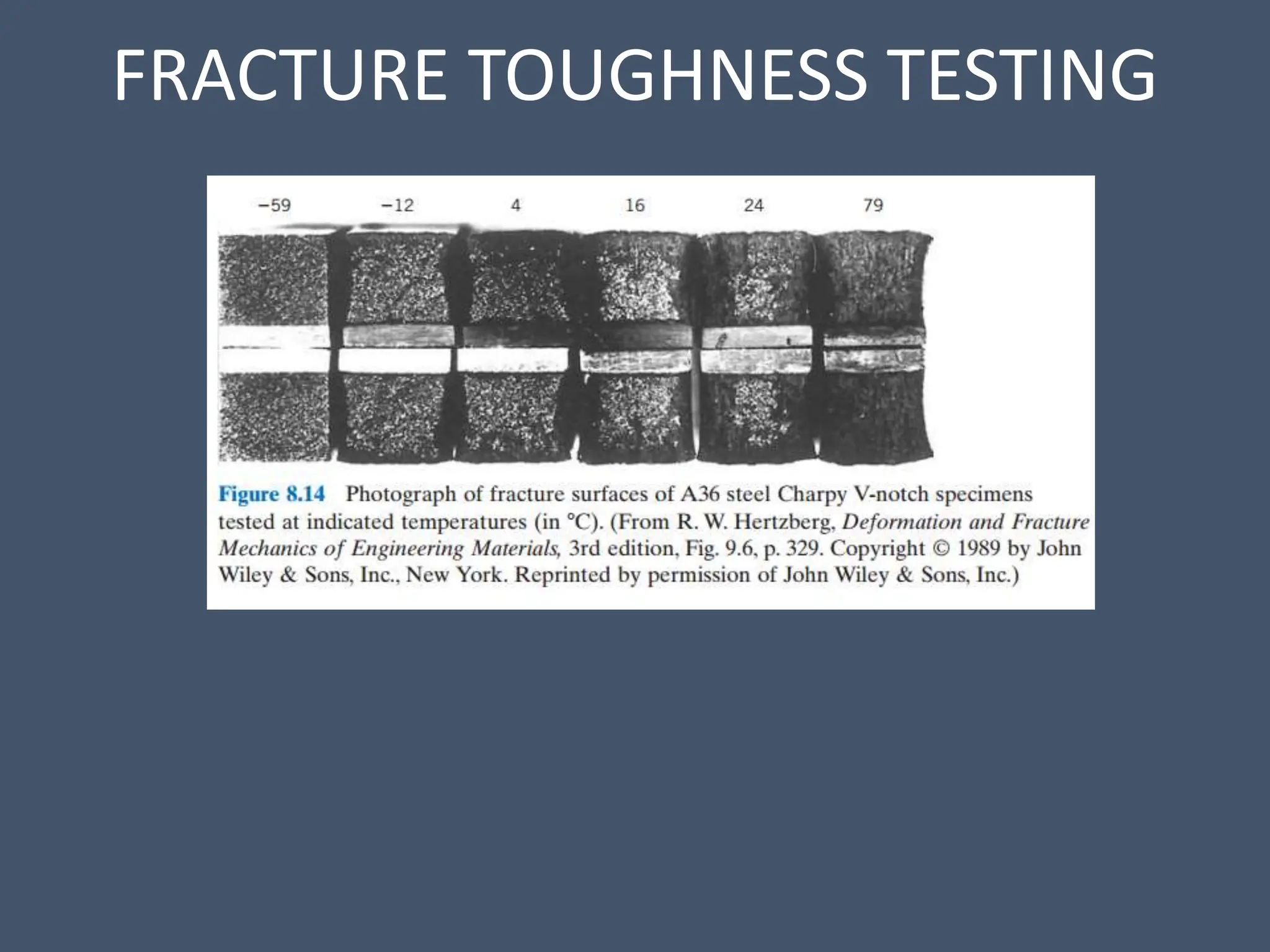

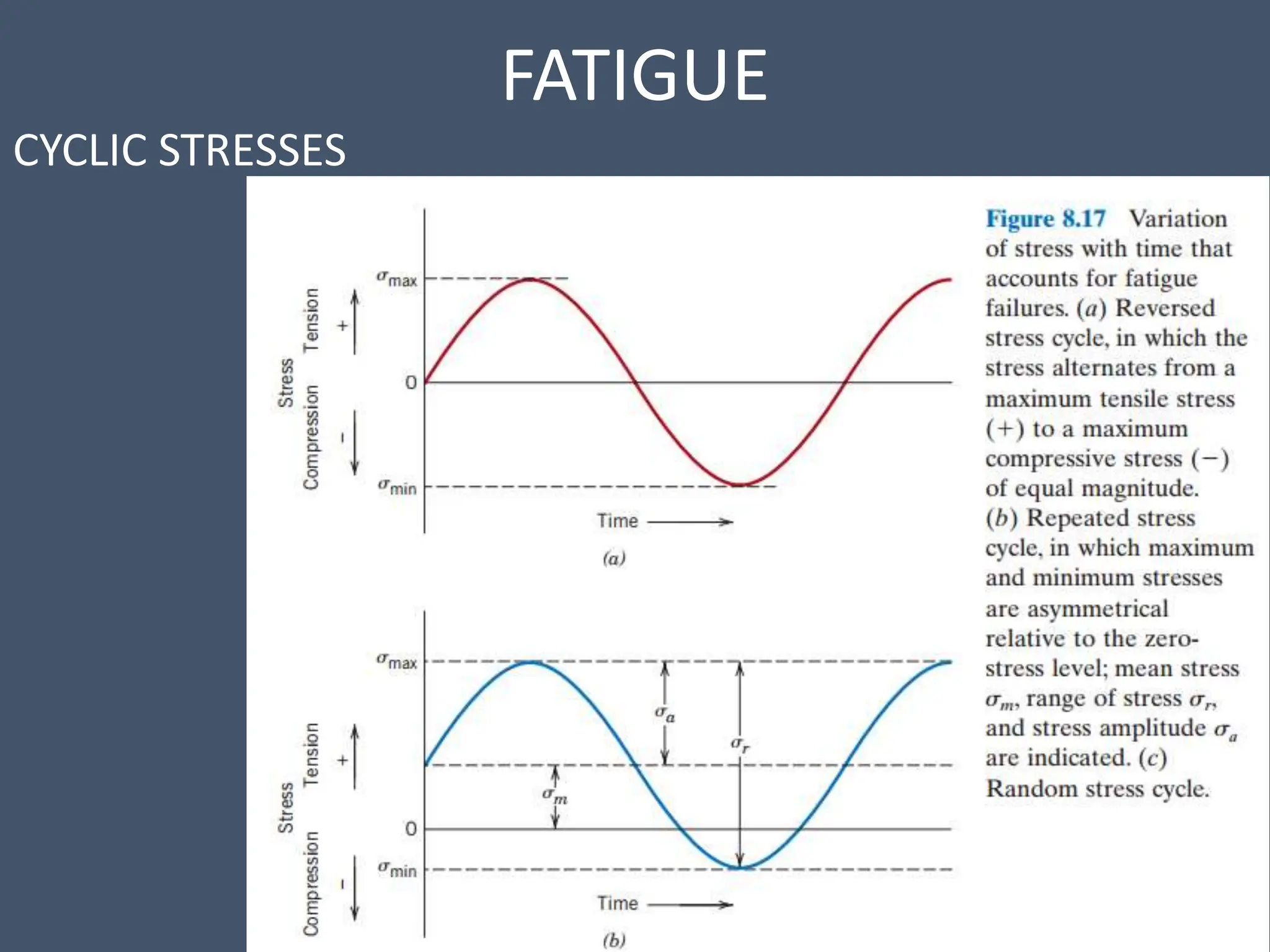

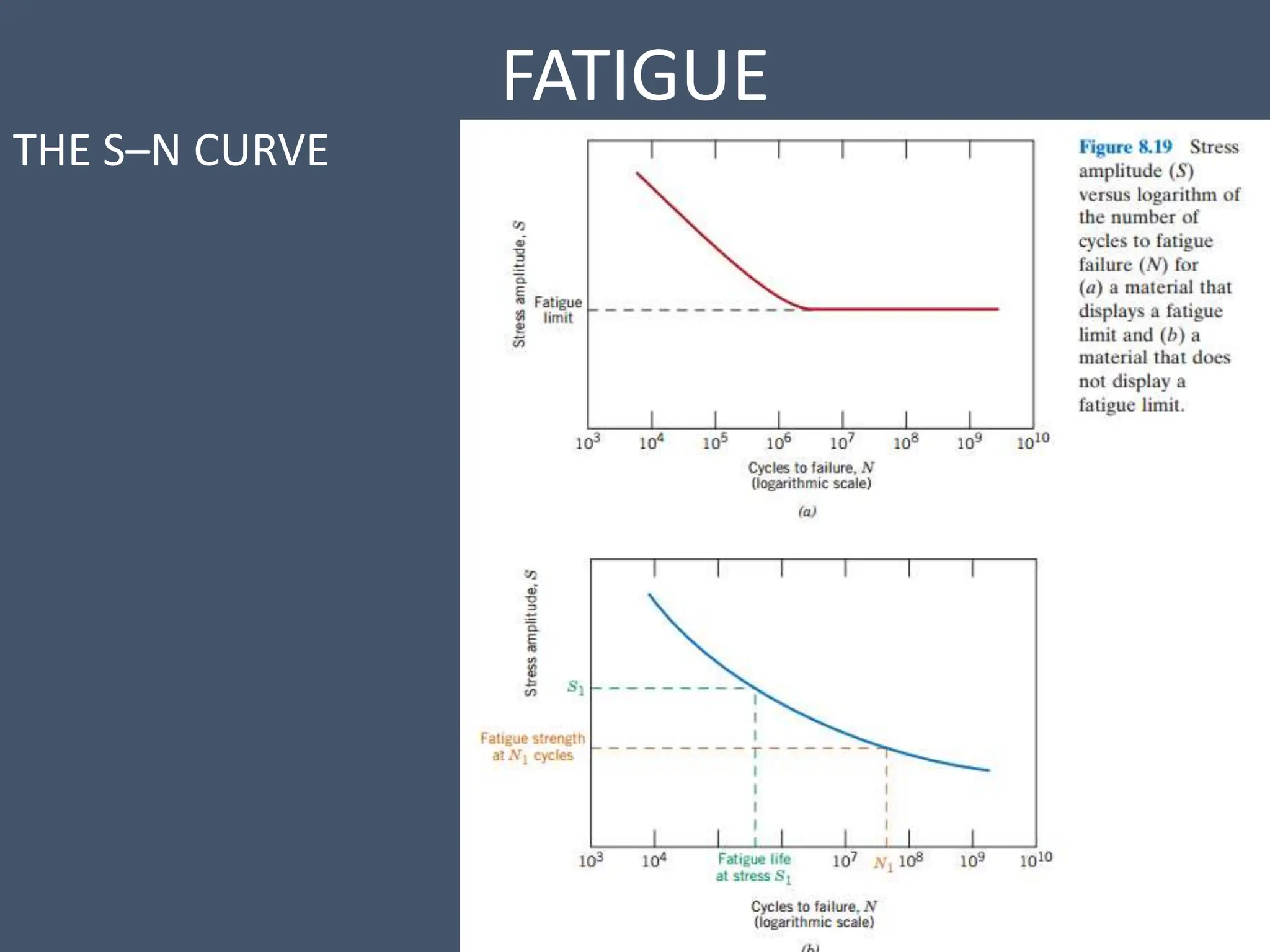

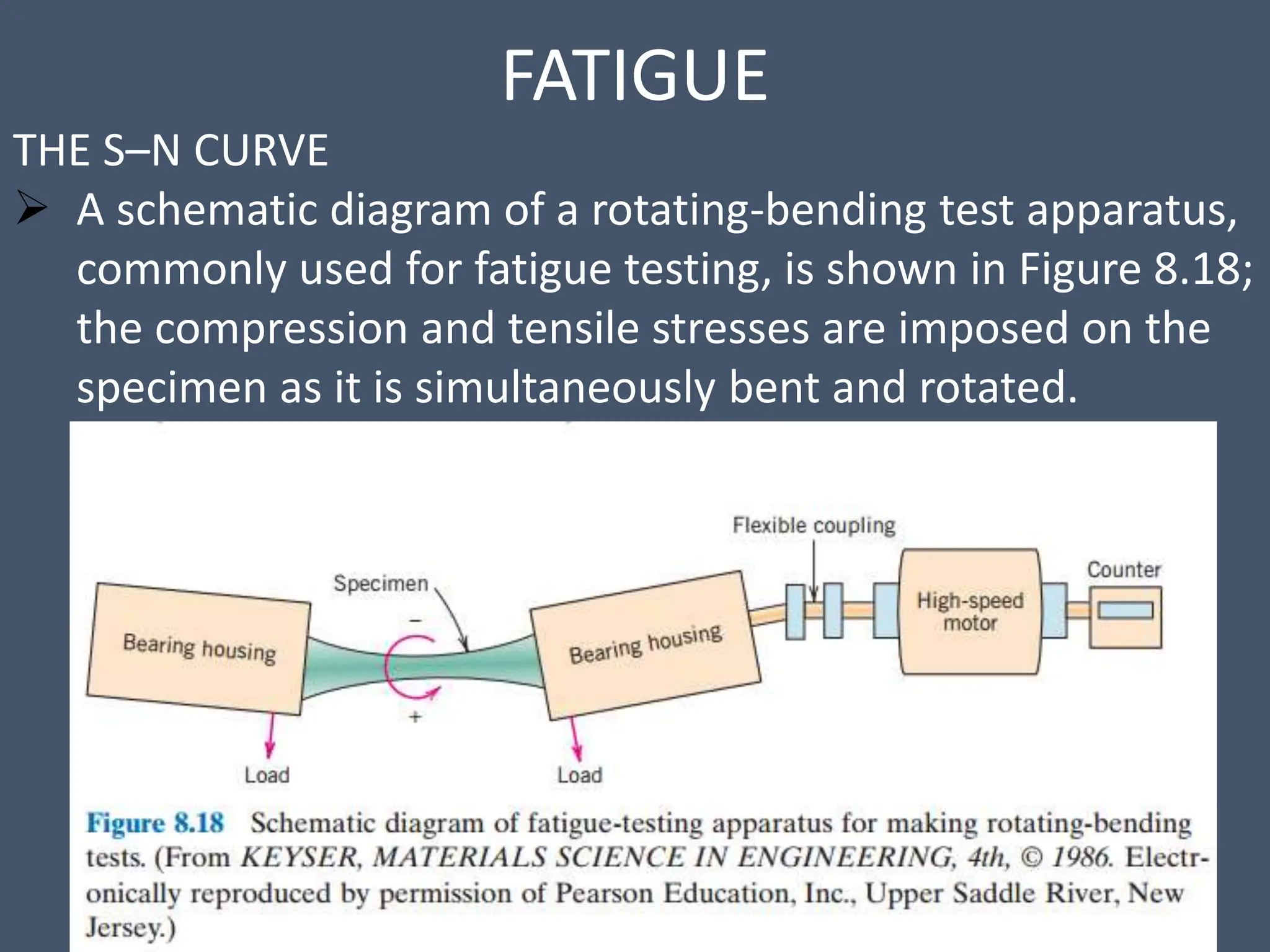

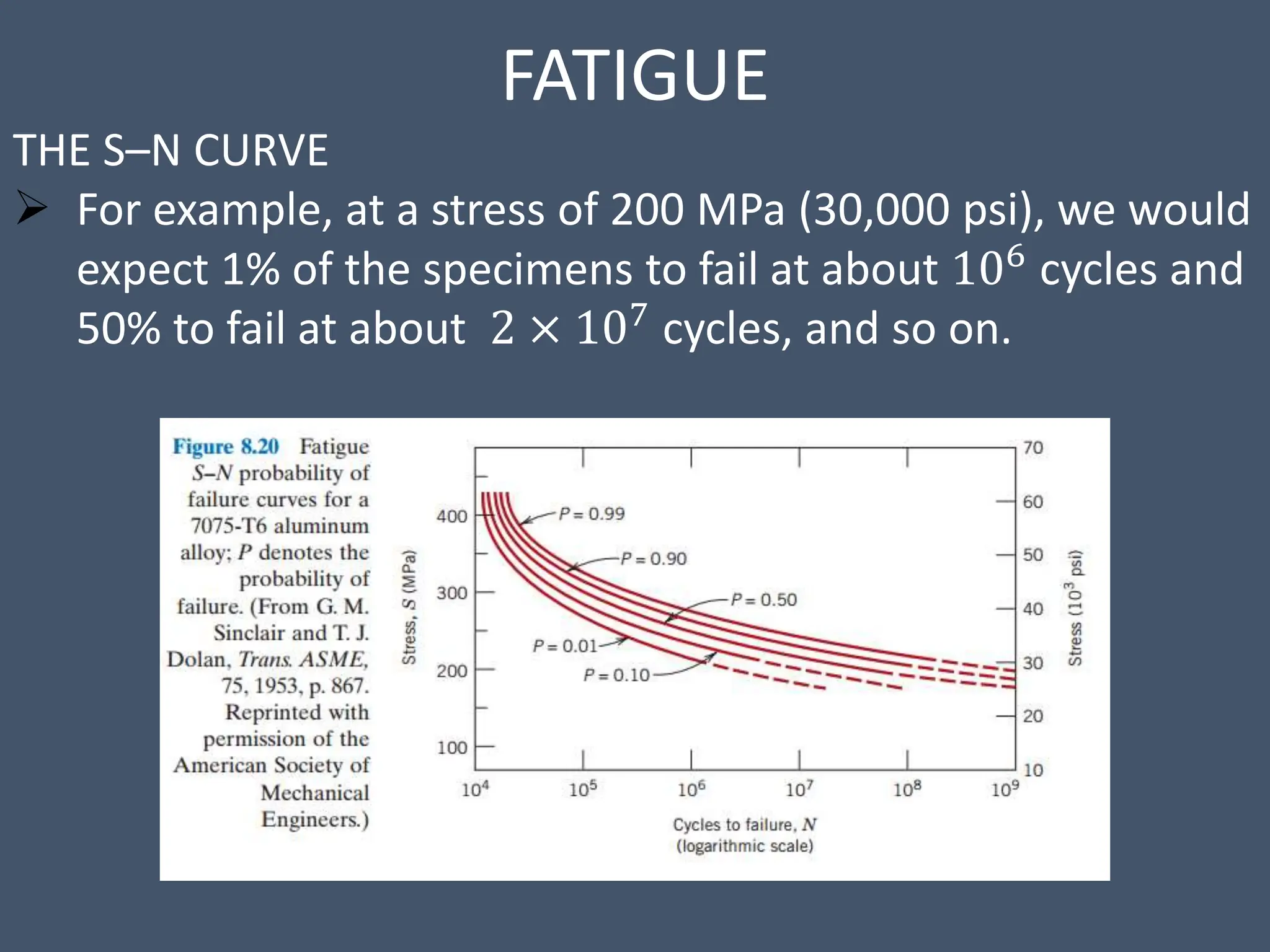

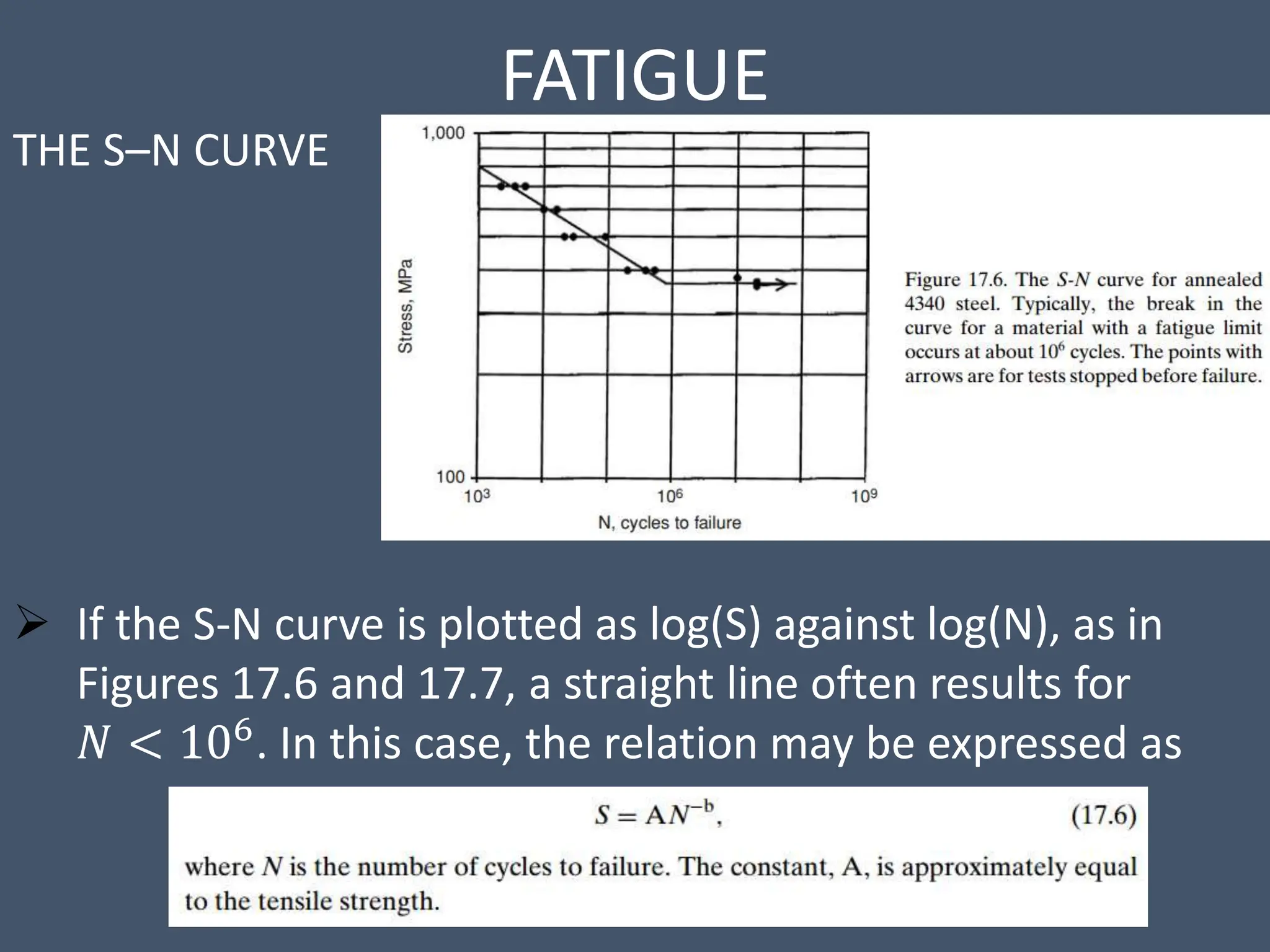

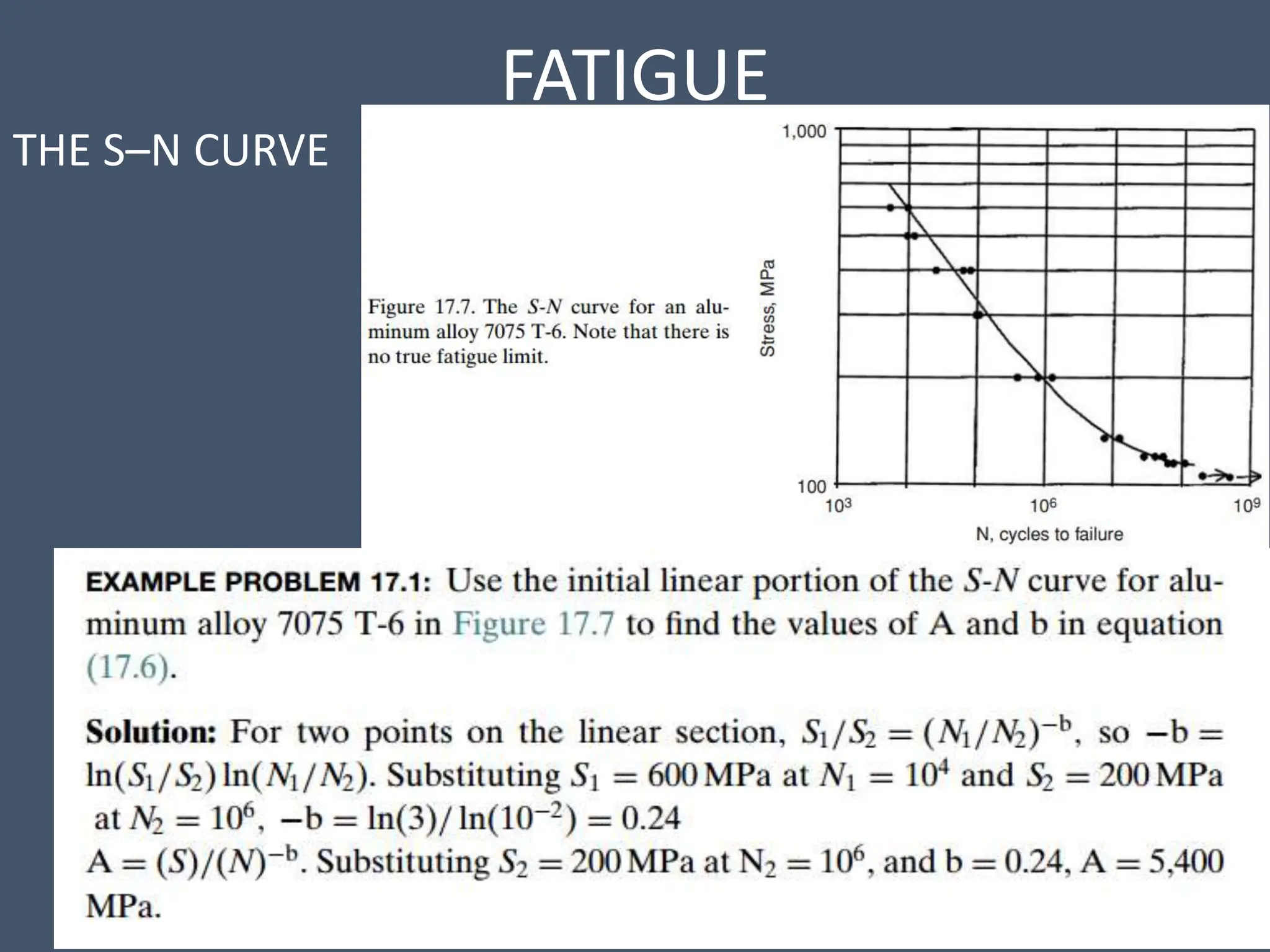

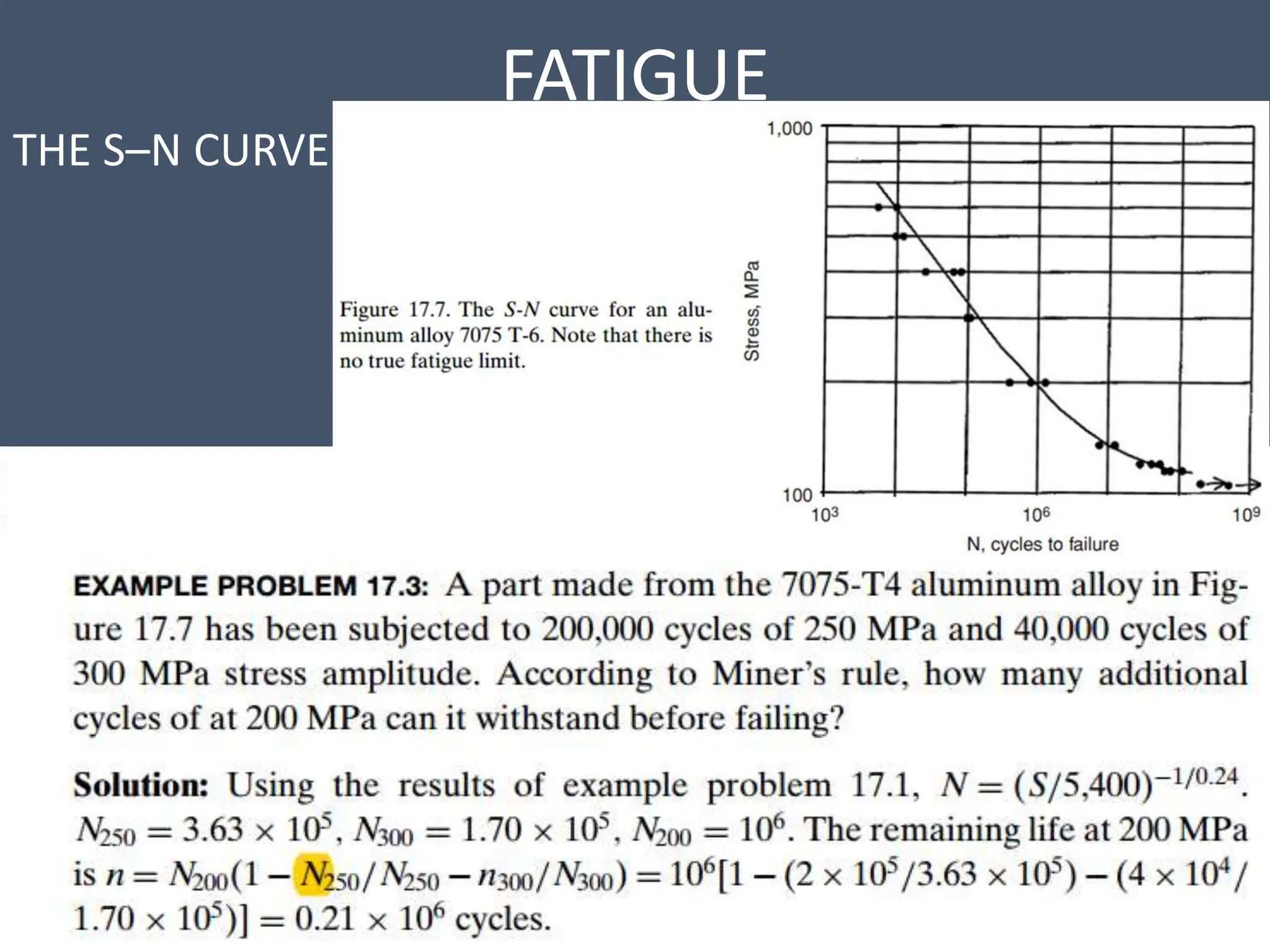

The document outlines the mechanical properties and testing of engineering materials, focusing on failure modes such as fracture and fatigue. It provides definitions and explanations for both ductile and brittle fractures, detailing testing methods for fracture toughness and the impact of environmental factors on fatigue life. Key points include the significance of proper material selection and design to prevent failures, as well as the quantitative assessments of fatigue behavior through statistical methods.