1. This document provides guidance for quantity surveyors on calculating embodied carbon emissions associated with building projects.

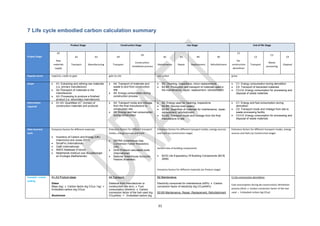

2. It defines key terms like embodied carbon, operational carbon, and outlines the different life cycle stages of a building according to the BS EN 15978:2011 standard.

3. The guidance recommends that quantity surveyors begin by estimating the product stage (cradle-to-gate) embodied carbon early in projects using material quantities and emission factors, and to involve other specialists to estimate emissions from later life cycle stages as more information becomes available.