This document provides information on composed/comprised, feminist criticism, lesbian/gay/queer criticism, and terms used in these types of literary analysis.

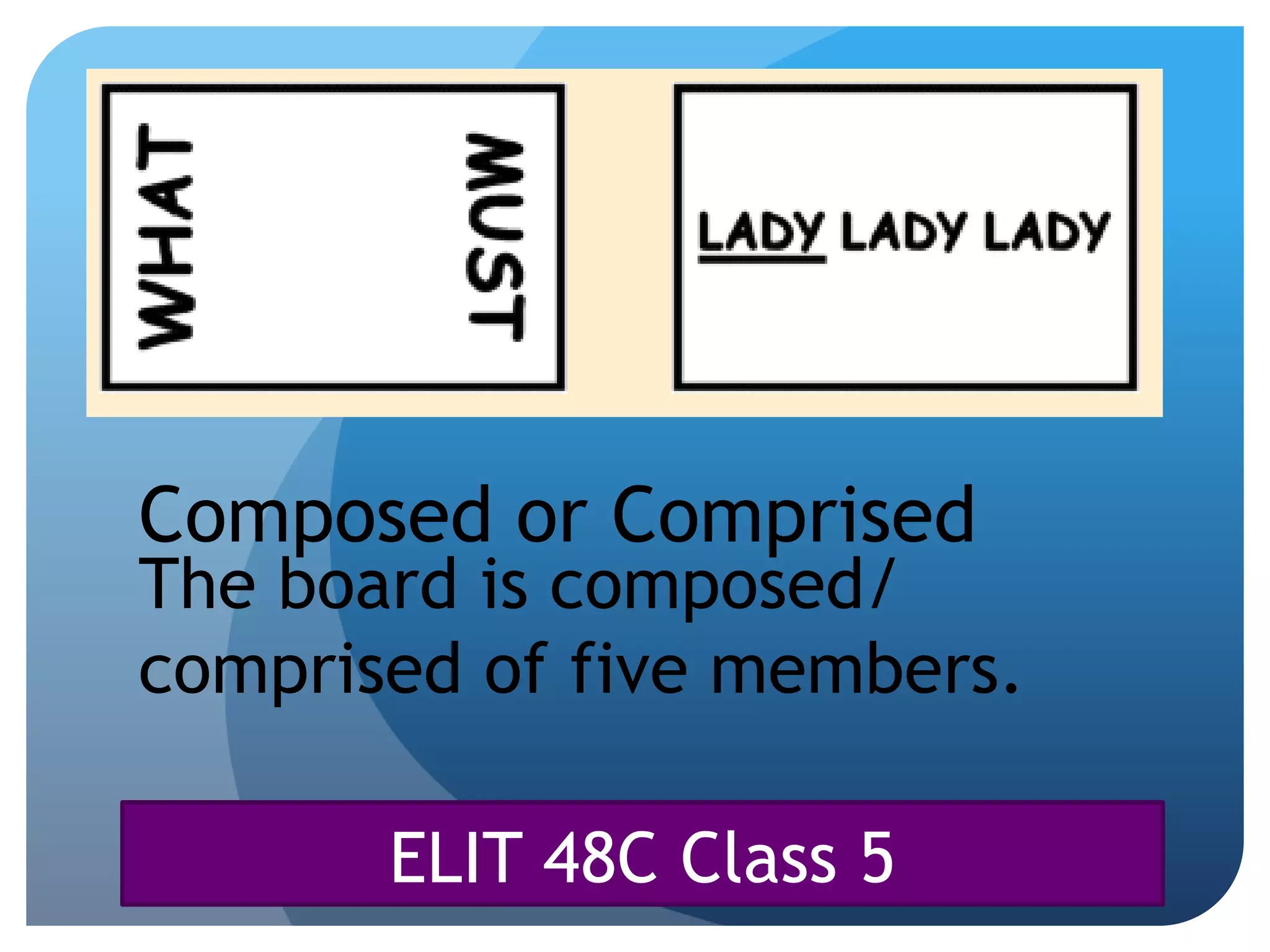

It explains that "composed" means made up of some or all parts, while "comprise" means to contain all parts, with the whole coming before parts.

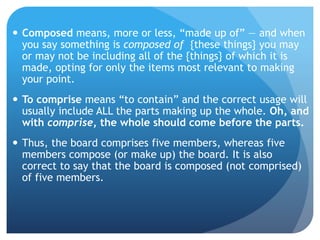

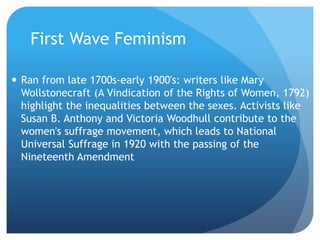

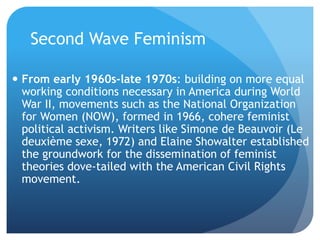

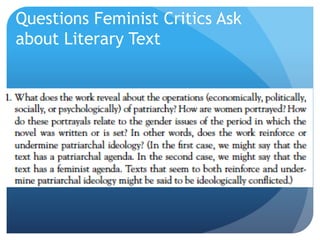

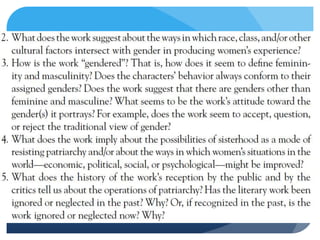

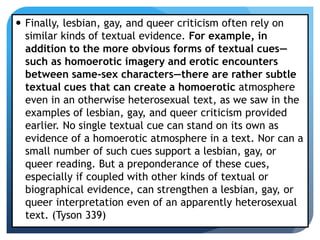

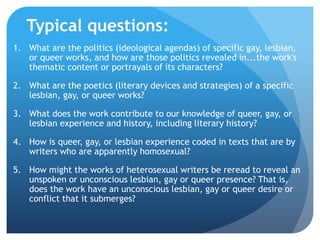

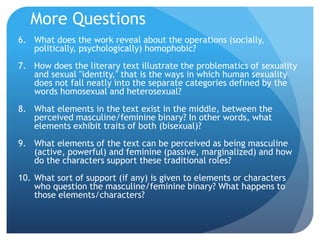

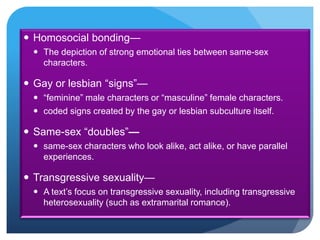

It then outlines the objectives and waves of feminist criticism, focusing on uncovering misogyny and the female experience. It also summarizes lesbian, gay, and queer criticism in examining oppression beyond sexism. Finally, it lists common terms and textual clues used in these analyses, such as homosocial bonding and same-sex doubles. Typical questions asked by these critiques

![ Feminist criticism is concerned with “the ways in which

literature (and other cultural productions) reinforce or

undermine the economic, political, social, and

psychological oppression of women" (Tyson). This school of

theory looks at how aspects of our culture are inherently

patriarchal (male dominated) and “this critique strives to

expose the explicit and implicit misogyny in male writing

about women" (Richter 1346). This misogyny, Tyson reminds

us, can extend into diverse areas of our culture: "Perhaps

the most chilling example [...] is found in the world of

modern medicine, where drugs prescribed for both sexes

often have been tested on male subjects only" (83).

Feminist Theory and Criticism](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/elit48cclass5postqhqcomposedvscomprised-150421075414-conversion-gate01/85/Elit-48-c-class-5-post-qhq-composed-vs-comprised-5-320.jpg)

![Third Wave Feminism

From early 1990s-present: resisting the perceived

essentialist (over generalized, over simplified) ideologies and

a white, heterosexual, middle class focus of second wave

feminism, third wave feminism borrows from post-structural

and contemporary gender and race theories to expand on

marginalized populations' experiences. Writers like Alice

Walker work to “reconcile [feminism] with the concerns of

the black community [and] the survival and wholeness of her

people, men and women both, and for the promotion of

dialog and community as well as for the valorization of

women and of all the varieties of work women perform"

(Tyson 97).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/elit48cclass5postqhqcomposedvscomprised-150421075414-conversion-gate01/85/Elit-48-c-class-5-post-qhq-composed-vs-comprised-10-320.jpg)

![1. How [or] has patriarchal language effected our perspectives and

paradigms?

a. Q: Can specific uses of language, such as congressman, fireman, or

Spanish, such as “hermanos” being able to refer to as both brothers and

sisters, be sexist?

2. Can we truly break away from a patriarchal society? How/why or why not?

a. Q: The hard times in America have taken over hundreds of years to resolve,

but we still have ghosts lingering—slavery and racism for example. With

that being said, is it even possible for us to move completely out of a

patriarchal society into a world were feminism is no longer necessary?

3. What role does power play in the disconnection from patriarchal

ideologies?

4. How is feminist criticism associated with “giving a voice to the voiceless?”

5. How does the patriarchal gender role affect women in their older years?

6. Why and how are female feminists undermined by the patriarchy?

QHQs Feminist Criticism](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/elit48cclass5postqhqcomposedvscomprised-150421075414-conversion-gate01/85/Elit-48-c-class-5-post-qhq-composed-vs-comprised-24-320.jpg)