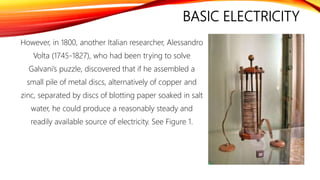

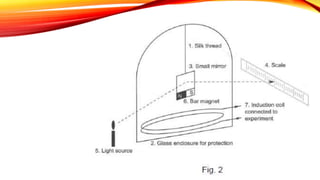

The document provides an overview of basic electricity concepts, including the properties and functions of electrical elements like circuits, magnets, and capacitors. It traces historical experiments by notable figures like Benjamin Franklin, Luigi Galvani, and Michael Faraday, highlighting their contributions to the understanding of electricity and magnetism. Key principles such as electromagnetism, safety precautions, and the importance of teamwork in experiments are also discussed.