The document discusses the complex relationship of E.E. Cummings with visual poetry and its interpretation, illustrating how his unique style challenges readers to engage deeply with the text. It explores the influences on Cummings' work, including his childhood, experiences in war, exposure to Freudian theories, and personal relationships, emphasizing that while influenced by various factors, his artistry was a product of deliberate experimentation. Ultimately, the document highlights Cummings' significant impact on poetry and the lasting legacy of his unconventional methods.

![2

Complicated or not, Cummings certainly had a significant impact upon literature,

particularly poetry. He brought an entirely new concept to visual poetry. In doing so, he

accomplished what some noteworthy predecessors were unable to do: force the reader to engage

the poem as if he were the speaker himself. Mimicking Cummings, it is hard to garner the same

esteem because it is easy to miss Cummings' point: it is not what you read, but how you say it.

Sadly, though, his powerful way of affecting the visual arrangement of words is mostly what

Cummings is famous for, even though that is just a small part of his overall plethora of literature.

These aspects of the poet bring out two different things to consider when trying to know what

influenced Cummings. Already mentioned is the inspiration for why he created a new form of

visual poetry. What, though, influenced his actual subjects? Four different periods or events in

his life answer that question.

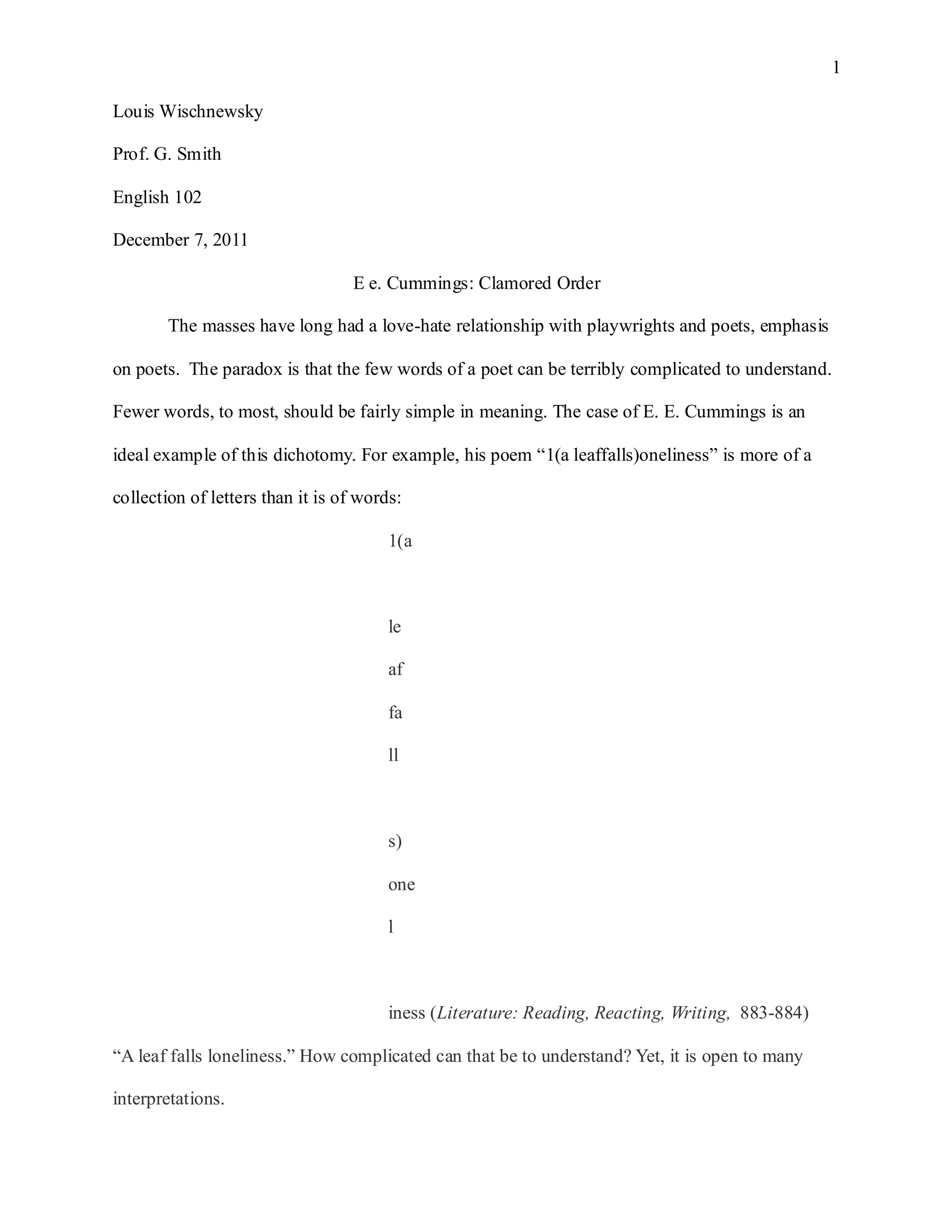

Looking pre-Cummings, yes, “concrete” or visual (also called emblem poetry) – poems

whose words are arranged in shapes – had been around for a long time (Kirszner and Mandel,

801,1007-1008). For example, long before Cummings, George Herbert created a visual poem

with “Easter Wings” (1008). “Randomly arranged words,” however, are a distinctive Cummings

trademark (see poem in opening paragraph). Herbert's poem was revolutionary in that it created a

visual image. It did not, however, cause the reader to think with varied emotion or even varied

pace. Poems like Cummings' “a leaf [...]”, though, does something totally different: it forces the

reader to pause, to second guess what is being read. Is the first character an “L” or a “one?” Who

knows? And that is the point of the poem: to demonstrate to the reader that everyone knows they

are an individual, but what is an individual? Starting and stopping, reflecting on whether the

reader has interpreted what is written, what is history, the poem is a reflection of life: successes

sometimes, failures others. “Easter Egg” questions faith and admits sin while hoping for God's

mercy, but it requires the reader to put himself or herself into the emotion; it requires the reader](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eecummings-clamoredorder-111207023305-phpapp01/75/Ee-Cummings-Clamored-Order-2-2048.jpg)

![5

after the first world war was an influence, as well, motivating him to write “[in] a rather clumsy

and inadequate way” - but not so much in his poetry; The Enormous Room, is the reflection upon

that internment (Friedman, 23-24). As Eleanor Sickels explained, like many liberal bohemians of

the day, Cummings was initially interested in the ideal of egalitarian communism (229-232).

However, the Russian, or anti-Russian, influence was well after his most famous subject,

eroticism, had become his forte and made him a, in true Cummings fashion, reluctantly eager

capitalist (229-236). So while Cummings' adventures across the pond were influential, they were

hardly foundations of his motivations.

Rather, according to Milton A. Cohen, Cummings had a profound affinity toward Freud

and his theories. Freudian influence on the poet is largely unknown, particularly Cummings'

poetry from the late 1910s and early 1920s (592). In fact, a claim that Freudian influence upon

Cummings during that period is profound would be dead on. To begin with, Cummings was

unique among bohemian Modernists in that he not only accepted Freudian theory, Cummings

actually incorporated, or attempted to, into his life (591).

The evidence is blatant: not only do Cummings' works from that period have a greater

frequency, and more intense elicit references than other periods of his life, there was the Elaine

Orr affair that only amplified his misconception of what Freud was saying. Cummings figured,

with his own interpretation of Freud, that Orr's pregnancy was her problem, not his. His reaction,

denial that he sired the child, reflects more of a lack of initial self-confidence in the theory. Here

was Scofield Thayer, the poet's college mentor, introducing and promoting Freudian philosophy

on Cummings' young mind but when “Jack Death” came knocking, suddenly Thayer is not a

Freudian practitioner (592, 594-595). Neither was Orr, whom Cummings surely thought was a

Freud disciple, as well.

The end result is a transition from obvious suggestion, prior to the affair, in “wanta](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eecummings-clamoredorder-111207023305-phpapp01/75/Ee-Cummings-Clamored-Order-5-2048.jpg)