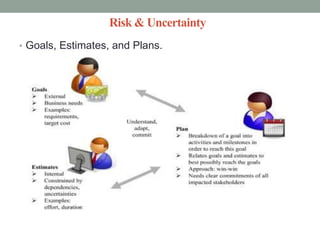

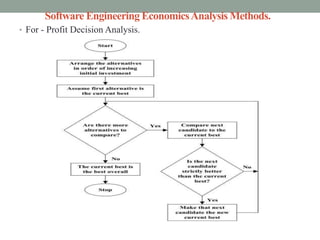

The document discusses software engineering economics, emphasizing the alignment of software decisions with business goals and various fundamental concepts such as finance, accounting, and decision-making processes. It outlines the life cycle of software engineering economics, including product development, project management, and investment decisions, while also addressing risk and uncertainty in decision-making. Moreover, the text covers analysis methods used in for-profit and non-profit organizations, highlighting techniques such as cost-benefit analysis and return on investment.