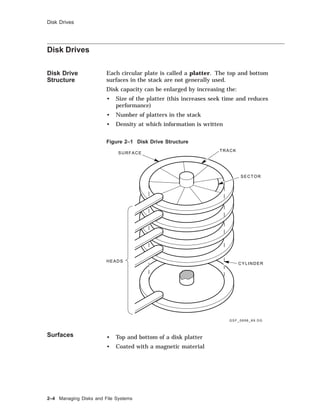

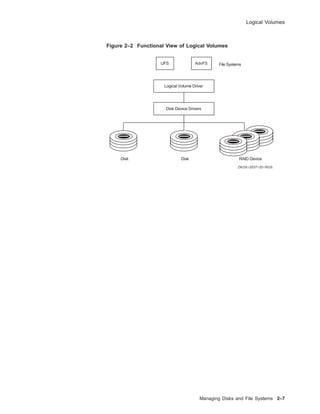

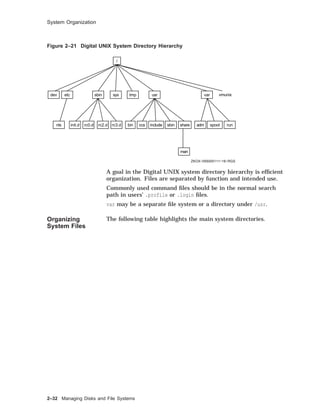

This document provides an overview of Digital UNIX system administration and managing disks and file systems. It describes the responsibilities of a system manager, the UNIX software environment including the kernel and features of Digital UNIX. It discusses system internals such as process creation, scheduling, and memory management. It also covers superuser privileges, the root login procedure, and using the Common Desktop Environment for administration tasks. Regarding disk and file system management, it details disk drive structure, logical volumes, partitions, file systems, and using tools like disktab to derive disk parameters.

![About This Course

Course

Conventions

Table 1 gives an explanation of the conventions used in this

course.

Table 1 Conventions Used in This Course

Convention Meaning

keyword Keywords and new concepts are displayed in this

type.

examples Examples, commands, options and pathnames

appear in this type.

command(x) Cross-references to command documentation

include the section number in the reference

pages. For example, fstab(5) means fstab is

referenced in Section 5.

$ A dollar sign represents the user prompt.

# A number sign represents the superuser prompt.

bold Within interactive examples, boldface type

indicates user input.

key The box symbol indicates that the named key on

the keyboard is pressed.

.

.

.

In examples, a vertical ellipsis indicates that not

all of the lines of the example are shown.

[ ] In syntax descriptions, brackets indicate items

that are optional.

variable In syntax descriptions, this type indicates items

that are variable.

.

.

.

In syntax descriptions, an ellipsis indicates the

item may be repeated.

xxvi](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-26-320.jpg)

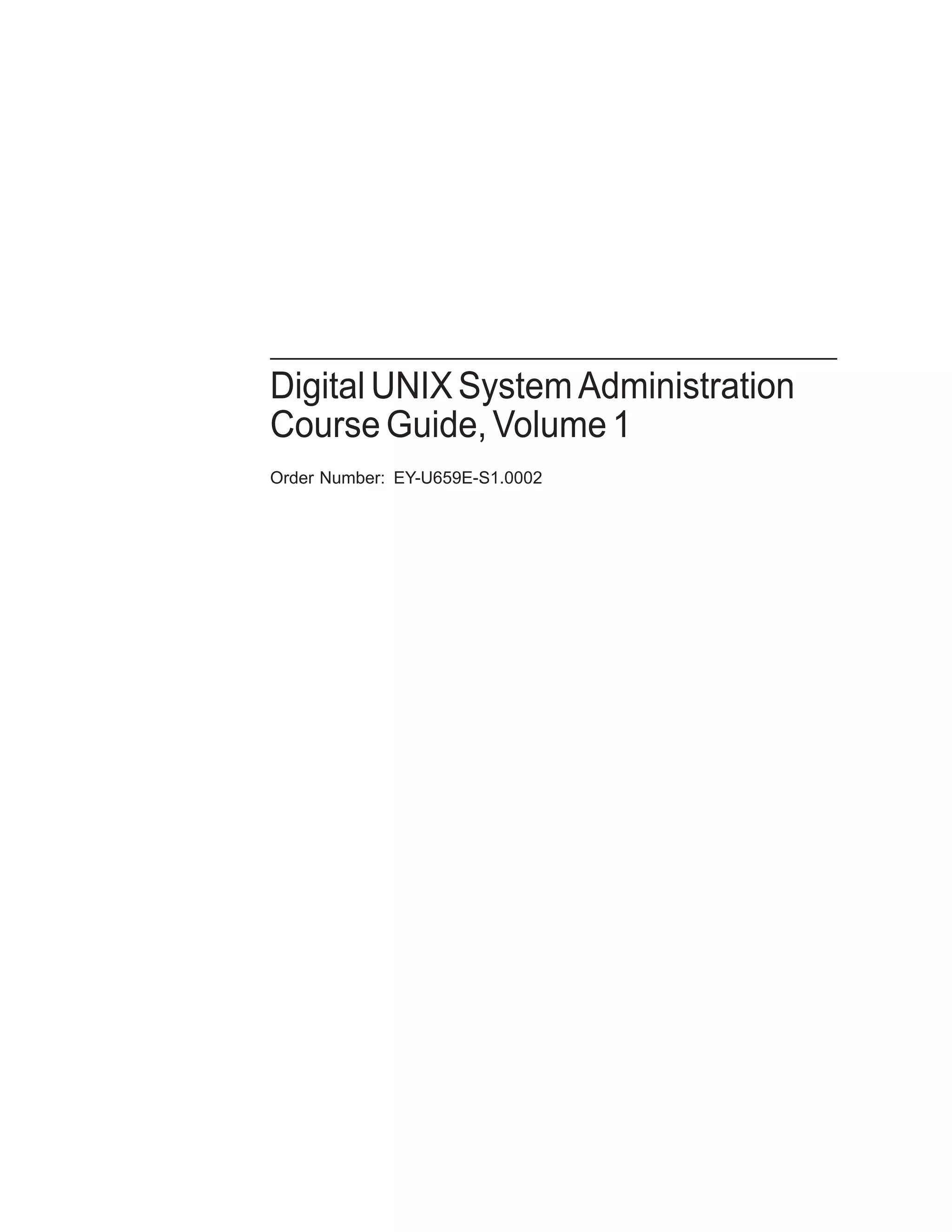

![Partitions and File Systems

Partition Offset Size (sectors)

Block Size

(bytes)

Fragment

Size (bytes)

d 393216 301986 8192 1024

e 695202 301986 8192 1024

f 997188 301986 8192 1024

g 393216 819200 8192 1024

h 1212416 86758 8192 1024

For more information on any type of disk, see that type in the

Reference Pages; for example, rz(7).

The following example shows a section of an /etc/disktab file.

Example 2–2 An /etc/disktab File

# Disk geometry and partition layout tables.

# Key:

# ty type of disk

# dt drive type (SCSI MSCP etc.)

# ns #sectors/track

# nt #tracks/cylinder

# nc #cylinders/disk

# o[a-h] partition offset

# P[a-h] partition sizes in sectors

# b[a-h] partition block sizes in bytes

# f[a-h] partition fragment sizes in bytes

rz56|RZ56|DEC RZ56 Winchester:

:ty=Winchester:dt=SCSI:ns#54:nt#15:nc#1632:

:oa#0:pa#131072:ba#8192:fa#1024:

:ob#131072:pb#262144:bb#8192:fb#1024:

:oc#0:pc#1299174:bc#8192:fc#1024:

:od#393216:pd#301986:bd#8192:fd#1024:

:oe#695202:pe#301986:be#8192:fe#1024:

:of#997188:pf#301986:bf#8192:ff#1024:

:og#393216:pg#819200:bg#8192:fg#1024:

:oh#1212416:ph#86758:bh#8192:fh#1024:

Managing Disks and File Systems 2–11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-69-320.jpg)

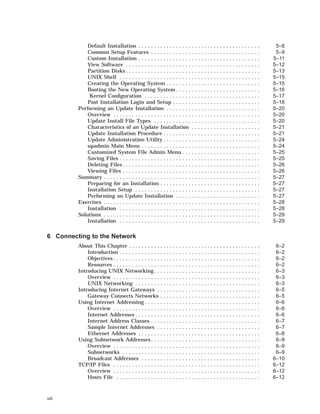

![Viewing and Changing Partition Sizes

Viewing and Changing Partition Sizes

Overview In general, you change the partitions during the initial

installation or when your file system is running out of space.

The disklabel command is available in the Digital UNIX

standalone environment. You must have superuser privileges to

use the disklabel command.

The partition size and offset are in 512-byte sectors. The offset is

the starting sector number for the partition.

To display the current partition sizes, use disklabel -r with the

raw device name for partition a or c. The example shows how to

display a disk label.

Example 2–3 Displaying the Disk Label

# disklabel -r /dev/rrz0a

# /dev/rrz0a:

type: SCSI 1

disk: rz55 2

label: 3

flags: 4

bytes/sector: 512 5

sectors/track: 36

tracks/cylinder: 15

sectors/cylinder: 540

cylinders: 1224

rpm: 3600 6

interleave: 1

trackskew: 0

cylinderskew: 0

headswitch: 0 # milliseconds

track-to-track seek: 0 # milliseconds

drivedata: 0 7

7 partitions: 8

# size offset fstype [fsize bsize cpg]

a: 40960 0 4.2BSD 1024 8192 16 # (Cyl. 0 - 75*)

b: 122880 40960 4.2BSD 1024 8192 16 # (Cyl. 75*- 303*)

c: 649040 0 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 0 - 1201*)

d: 152446 163840 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 303*- 585*)

e: 152446 316286 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 585*- 868*)

f: 180308 468732 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 868*- 1201*)

g: 485200 163840 4.2BSD 1024 8192 16 # (Cyl. 303*- 1201*)

#

1 Controller type; for example, SCSI, ESDI, SMD, MSCP

2 Disk type name

3 Optional label

4 Flags; for example, removable, RAMDISK, ECC

5 Disk geometry section

2–20 Managing Disks and File Systems](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-78-320.jpg)

![Viewing and Changing Partition Sizes

Example 2–4 Expanding a Partition

# /sbin/disklabel -r /dev/rrz2a

# /dev/rrz2a:

type: SCSI

disk: rz23

label:

.

.

.

8 partitions:

# size offset fstype [fsize bsize cpg]

a: 40960 0 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 0 - 155*)

b: 58498 40960 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 155*- 376*)

c: 204864 0 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 0 - 775)

d: 35135 99458 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 376*- 509*)

e: 35135 134593 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 509*- 642*)

f: 35136 169728 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 642*- 775*)

g: 105406 99458 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 376*- 775*)

h: 70271 134593 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 509*- 775*)

# /sbin/disklabel -e -r /dev/rrz2a

(invokes an editor; we change partition a size from 40960 to 99458)

type: SCSI

disk: rz23

label:

flags:

bytes/sector: 512

sectors/track: 33

tracks/cylinder: 8

sectors/cylinder: 264

cylinders: 776

rpm: 3600

interleave: 1

trackskew: 0

cylinderskew: 0

headswitch: 0 # milliseconds

track-to-track seek: 0 # milliseconds

drivedata: 0

8 partitions:

# size offset fstype [fsize bsize cpg]

a: 99458 0 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 0 - 155*)

b: 58498 40960 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 155*- 376*)

c: 204864 0 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 0 - 775)

d: 35135 99458 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 376*- 509*)

e: 35135 134593 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 509*- 642*)

f: 35136 169728 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 642*- 775*)

g: 105406 99458 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 376*- 775*)

h: 70271 134593 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 509*- 775*)

~

(when you exit the editor, you will be prompted)

write new label? [y]: Return

(continued on next page)

Managing Disks and File Systems 2–23](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-81-320.jpg)

![Viewing and Changing Partition Sizes

Example 2–4 (Cont.) Expanding a Partition

# /sbin/disklabel -r /dev/rrz2a

# /dev/rrz2a:

type: SCSI

disk: rz23

label:

.

.

.

8 partitions:

# size offset fstype [fsize bsize cpg]

a: 99458 0 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 0 - 376*)

b: 58498 40960 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 155*- 376*)

c: 204864 0 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 0 - 775)

d: 35135 99458 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 376*- 509*)

e: 35135 134593 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 509*- 642*)

f: 35136 169728 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 642*- 775*)

g: 105406 99458 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 376*- 775*)

h: 70271 134593 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 509*- 775*)

We can display the disk label again, showing the changes we have

made. Notice the cylinder numbers for partition a have been

automatically updated.

Repartitioning

a Disk

The following are suggestions for repartitioning a disk.

• Increase a partition if a file system or swap area is running

out of space.

• To make backups easier, size partitions based on your backup

device’s storage capacity.

• Create separate file systems on separate disks for /, /usr, var,

and users’ home directories to improve performance and make

backups easier.

• Divide swap space between two partitions on different disks to

improve performance.

2–24 Managing Disks and File Systems](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-82-320.jpg)

![Creating a UFS File System

Creating a UFS File System

Overview You do not need to create the root and /usr file systems before

installing the system; these are created as part of the installation.

If you want separate file systems for users’ home directories,

layered products, or other files, you must create these file systems

after the installation.

Using the

newfs

Command

When you have a new partition or logical volume, you must

prepare it to hold files by creating a file system.

To create a new file system, use the newfs(8) command.

newfs [ -N ] [ options ] device type

-N Displays file system parameters without creating a file

system.

options Options depend on the type of file system; for example,

for UFS you can specify the size in sectors or the

number of bytes per inode. See newfs(8) for more

options.

device The unmounted, raw device name; for example, /dev

/rrz1a.

type The disk type from /etc/disktab.

You must be root to use newfs.

The newfs command destroys all data on an existing file system.

The following example shows how to create a UFS file system

with a block size of 8192 bytes and fragment size of 1024 bytes on

partition c of an RZ28 disk, which is drive 1.

Managing Disks and File Systems 2–41](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-99-320.jpg)

![Checking a UNIX File System

Checking a UNIX File System

When to Check

File Systems

File systems are checked automatically when the system starts.

You should check a file system before mounting it manually or

backing it up.

Using the fsck

Command

Use the fsck(8) command to check a UNIX file system. Advanced

file systems and network file systems do not need to be checked.

The fsck command looks for and corrects inconsistencies such as:

• Unreferenced inodes

• Link count number in inode is too large

• Missing blocks in the free list

• Blocks in the free list that are also in files, or blocks that are

in two files

• Incorrect counts in the superblock

fsck [ options ] [ filesystem ]

options Some options for UFS file systems:

-p Checks and corrects a set of

inconsistencies. If it encounters other

errors, it exits.

Without the -p option, fsck works

interactively, prompting before each

correction.

-b block Specifies the block to use as the

superblock. (Block 32 is usually used

as alternate superblock.)

-y Assumes a yes response to all prompts.

-n Assumes a no response to all prompts.

filesystem The raw device name for the file system you want

checked; for example, /dev/rrz1a. If you do not specify

a file system, all file systems in /etc/fstab are checked.

Orphaned files are put in the lost+found directory, using the inode

as a name. If the lost+found directory does not exist, you can

create it with the mklost+found(8) command. If you choose not

to create it, it will be created automatically if orphaned files are

found.

You must be root to use fsck.

Check file systems when they are unmounted. Since the root file

system cannot be unmounted, check it in single-user mode. This

will prevent fsck reporting and attempting to fix inconsistencies

due to normal system operations. Example 2–6 shows how to

invoke the fsck command.

Managing Disks and File Systems 2–43](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-101-320.jpg)

![Mounting and Unmounting File Systems

Figure 2–28 File Systems After Mounting

/

dev etc sbin tmp usr

file1 file2 file3

bin lib sbin share sys

ZKOX−055000111−08−RGS

1

2

Disk 1 is the system disk containing the root file system. Disk 2

is another disk containing a file system. Before it is mounted, the

files on it are not accessible.

Once it is mounted, the files are accessible through the directory

mount point, in this case /usr.

This figure illustrates another important point. Usually you

will not mount a file system on a directory that contains files.

However, you can do so without deleting or damaging the files.

The files will be invisible and inaccessible until the file system is

unmounted.

The mount command is available in the Digital UNIX standalone

environment.

The root file system is mounted automatically when the system is

booted, and cannot be unmounted.

Using the

mount

Command

To mount a file system under an existing directory, use mount.

mount [ options ] [ device ] [ mountpoint ]

options Some options include:

-a Mounts all file systems listed in /etc

/fstab

-t Specifies a type of file system to mount;

for example

# mount -a -t ufs

-r Specifies mount with read-only access

-o Specifies file system specific options

device The special device name

mountpoint The existing directory to mount the file system

under

2–46 Managing Disks and File Systems](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-104-320.jpg)

![Mounting and Unmounting File Systems

Using the

umount

Command

Use the umount command to unmount a file system. The format

for umount is:

umount [ options ] [ mountpoint ]

options Some options include:

-A Attempts to unmount all file systems

currently mounted

-a Unmounts all file systems listed in /etc

/fstab

-t Specifies a type of file system to unmount;

for example

# umount -a -t ufs

-h Specifies a host for unmounting all file

systems remotely mounted in /etc/fstab.

mountpoint The existing directory where the file system is

mounted

You must unmount a file system if you want to check it with fsck

or change its partition size with disklabel.

You cannot unmount a file system if one of the files or directories

is in use.

You cannot unmount the root file system. Example 2–9 shows

how to use the umount command.

Example 2–9 Using the umount Command

# mount

/dev/rz0a on / type ufs (rw)

/dev/rz0g on /usr type ufs (rw)

/dev/rz0h on /usr/users type ufs (rw)

/dev/rz1c on /usr/local type ufs (ro)

/usr/share/man@tinker on /usr/share/man type nfs (ro,bg,soft,nosuid)

# umount /usr/local

# umount /usr

umount /dev/rz0g: Mount device busy

# umount -h tinker

The following example shows the mount and umount commands.

Example 2–10 Mounting and Unmounting File Systems

# who 1

superman tty00 Apr 29 13:57

# ls /mnt 2

# pwd 3

/

(continued on next page)

Managing Disks and File Systems 2–49](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-107-320.jpg)

![Solutions

# disklabel -r /dev/rrz0a

# /dev/rrz0a:

type: SCSI

disk: rz55

label:

flags:

bytes/sector: 512

sectors/track: 36

tracks/cylinder: 15

sectors/cylinder: 540

cylinders: 1224

rpm: 3600

interleave: 1

trackskew: 0

cylinderskew: 0

headswitch: 0 # milliseconds

track-to-track seek: 0 # milliseconds

drivedata: 0

7 partitions:

# size offset fstype [fsize bsize cpg]

a: 40960 0 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 0 - 75*)

b: 122880 40960 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 75*- 303*)

c: 649040 0 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 0 - 1201*)

d: 152446 163840 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 303*- 585*)

e: 152446 316286 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 585*- 868*)

f: 180308 468732 unused 1024 8192 # (Cyl. 868*- 1201*)

g: 485200 163840 4.2BSD 1024 8192 16 # (Cyl. 303*- 1201*)

#

2. Editing the disk label without the -r option affects only the

copy in memory, not the label on the disk.

3. Displaying the disk label should show your changes: for

partition d, increase the size by 1000 but not the offset; if

partition e is adjacent to d, increase e’s offset by 1000 and

decrease its size by 1000. Add the disk name after the label:

field.

Creating a File

System

1. No solution required.

2. # newfs /dev/rrz1g RZ56

Checking a File

System

1. No solution required.

2. # fsck /dev/rrz1g

3. # fsck -y /dev/rrz1g

Mounting File

Systems

1. No solution required.

2. Solution varies.

# mount

/dev/rz0a on / type ufs (rw)

/dev/rz0g on /usr type ufs (rw)

/dev/rz0h on /usr/users type ufs (rw)

/dev/rz1c on /usr/local type ufs (ro)

Managing Disks and File Systems 2–57](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-115-320.jpg)

![Shutting Down and Rebooting the System

Methods

for System

Shutdown

There are a number of ways you can shut down and reboot your

UNIX system.

• Use the:

CDE Shutdown manager

shutdown command

halt or fasthalt command

init command

• Send a signal to the init process.

• Turn off the power.

Figure 3–1 provides an overview of various commands used to

shut down or reboot a UNIX system.

Figure 3–1 Overview of System Shutdown and Reboot

#

>>>

>>>

halt, fasthalt

ZKOX−055000111−09−RGS

reboot

shutdown −r, reboot

shutdown −h, init 0

shutdown, init s

Halt

Mode

Single

User

Mode

Multiuser

Mode

Using the

shutdown

Command

Use the shutdown command to halt, reboot, or return to single user

mode. The command provides the most consideration for other

users. You must be logged in as root to execute this command.

The format for the shutdown command is:

shutdown [-fhknr] time [warning-message]

The shutdown options are shown in Table 3–1.

3–4 System Shutdown and Startup](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-120-320.jpg)

![Shutting Down and Rebooting the System

Shutdown is complete when the system console displays single

user mode.

INIT: SINGLE USER MODE

#

You have superuser access to the system through the console,

using the Bourne shell to perform administrative tasks.

Prior to the transition from multiuser to single user mode, the

output from the process status (ps -aef) command might look like

the one shown in Example 3–1.

Example 3–1 Typical Multiuser Mode ps Output

UID PID PPID C STIME TTY TIME CMD

root 0 0 1.5 Aug 19 ?? 04:51:51 [kernel idle]

root 1 0 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.39 /sbin/init -sa

root 3 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.42 /sbin/kloadsrv

root 40 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 1:54.21 /sbin/update

root 113 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:01.15 /usr/sbin/syslogd

root 115 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.01 /usr/sbin/binlogd

root 177 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:53.15 /usr/sbin/routed -q

root 309 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.55 /usr/sbin/portmap

root 311 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.11 /usr/sbin/mountd -i

root 313 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.02 /usr/sbin/nfsd -t8 -u8

root 315 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.01 /usr/sbin/nfsiod 7

root 318 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.02 /usr/sbin/rpc.statd

root 320 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.05 /usr/sbin/rpc.lockd

root 346 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.03 /usr/sbin/dnalimd

root 349 346 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:05.28 /usr/sbin/dnaevld

root 381 346 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 3:01.33 /usr/sbin/dnascd

root 382 381 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.10 /usr/sbin/dnansd

root 383 381 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.37 /usr/sbin/dnaksd

root 387 346 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:10.55 /usr/sbin/dnsadv

root 429 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:03.10 /usr/sbin/dtssd

root 433 387 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.21 /usr/sbin/dnsclerk -U r

root 435 346 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.07 /usr/sbin/dnanoded

root 482 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.37 /usr/sbin/osaknmd

root 522 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:14.64 -accepting connections

root 542 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:03.79 /usr/sbin/xntpd -g -x -

root 576 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:04.26 /usr/sbin/os_mibs

root 579 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 1:37.92 /usr/sbin/snmpd

root 581 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 28:48.23 /usr/sbin/advfsd

root 592 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.17 /usr/sbin/inetd

root 625 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.60 /usr/sbin/cron

root 657 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.20 /usr/lbin/lpd

root 676 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.12 /usr/bin/mmeserver -con

root 690 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.49 /usr/dt/bin/dtlogin -da

root 702 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.84 lpsbootd -F /etc/lpsodb

root 705 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.02 /usr/sbin/getty /dev/la

root 706 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.02 /usr/sbin/getty /dev/la

root 707 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.02 /usr/sbin/getty /dev/la

root 708 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.02 /usr/sbin/getty /dev/la

root 709 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.02 /usr/sbin/getty /dev/la

root 710 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.02 /usr/sbin/getty /dev/la

root 711 1 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.02 /usr/sbin/getty /dev/la

root 712 690 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 38:37.93 /usr/bin/X11/X :0 -auth

root 781 592 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.10 rpc.ttdbserverd

3–6 System Shutdown and Startup](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-122-320.jpg)

![Shutting Down and Rebooting the System

The ps -aef command output after transition to single user mode

might look like the one shown in Example 3–2. Notice how few

processes are running.

Example 3–2 Typical Single User ps Output

UID PID PPID C STIME TTY TIME CMD

root 0 0 1.5 Aug 19 ?? 04:51:51 [kernel idle]

root 1 0 0.0 Aug 19 ?? 0:00.39 /sbin/init -sa

root 4921 4744 0.0 Aug 26 ttyp1 0:01.27 ksh

root 20911 20901 0.0 15:47:22 ttypb 0:00.06 ps -aef

Complete

Shutdown

When used with the -h or -r options, the shutdown command

typically performs the following functions in addition to the

functions performed by the shutdown command when used with no

options:

• Runs the sync command to synchronize the disks

• Unmounts the file systems

• Halts the processor

If the command was shutdown -r, the shutdown command

automatically starts a reboot operation to return the system to

multiuser mode.

Using the halt

Command

to Stop the

Processor

Use the halt command to cause a transition from single user

mode to the halt state. Use it only if you are not going to restart

immediately. You can turn off the system power when the system

displays the console prompt.

The halt command:

• Logs the system halt in the event log and /var/adm/wtmp

• Kills running processes

• Synchronizes the disks

• Halts the processors

• Can be run only by root

Descriptions for the various options to the halt command are

shown in Table 3–2.

Table 3–2 halt Command Options

Option Function

-l Does not log the halt

-n Prevents the use of sync to write data to the disks and

does not log the halt

-q Causes a quick halt; does not log the halt and makes

no attempt to kill the system processes

System Shutdown and Startup 3–7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-123-320.jpg)

![Shutting Down and Rebooting the System

For example:

# halt

syncing disks... done

halting.... (transferring to monitor)

The halt is logged in /usr/adm/syslog.dated/date/auth.log.

Using the

fasthalt

Command

The fasthalt command halts the system and flags a subsequent

reboot not to carry out a file system consistency check (fsck).

The fasthalt command:

• Creates the file /fastboot, used by startup scripts to prevent

the execution of fsck

• Invokes the halt command to halt the processors

Note

Use the fasthalt command with extreme caution and

never use it unless you are certain that the file systems

are in excellent shape.

The format for the fasthalt command is:

fasthalt [-l -n -q]

The options for the fasthalt command are described in

Table 3–3.

Table 3–3 fasthalt Command Options

Option Function

-l Does not log the halt

-n Prevents the use of sync to write data to the disks and

does not log the halt

-q Causes a quick halt; does not log the halt and makes

no attempt to kill the system processes

Shutting Down

to Single User

Mode with init

Use the init command to shut down the system from multiuser

mode to single user mode.

The format for the command is:

init s

The init command scans the /etc/inittab file to determine which

commands and scripts must be run to bring the system to single

user mode.

3–8 System Shutdown and Startup](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-124-320.jpg)

![Shutting Down and Rebooting the System

Stopping the

Processor with

init

A Digital UNIX system may be halted with the init command.

The format for the command is:

init 0

The init command scans the /etc/inittab file to determine which

commands and scripts must be run to bring the system to halt

mode.

The init command may be executed in either multiuser or

single user mode. You would not normally use init to shut down

the system or halt the system unless you have provided ample

warning to the users with the wall command.

Other Methods

of Shutting

Down the

System

Other methods for shutting down the system include:

• Sending the TERM signal (15) to the init process brings the

system to single user mode.

• Sending the KILL signal (9) to the init process may bring the

system to console level.

• Turning off the power.

Note

These methods are not recommended for shutting down

a system because the results are unpredictable. The

best way to shut down the system is with the shutdown

command.

Rebooting the

System

If you make changes to system software or configuration files that

are executed only when the system is booted, you must reboot for

these changes to take effect. Also some devices, such as printers,

can become unusable for unknown reasons and require resetting,

which may not be possible without reinitializing the system.

Under these circumstances, you may have to reboot the system.

Using the

reboot

Command

The reboot command normally stops all processes, synchronizes

the disks, logs the reboot, and writes a shutdown entry into the

login accounting file.

The reboot command does not provide a time delay, nor does it

inform users of an impending shutdown and reboot. Do not use

the reboot command if users are logged in; use the shutdown -r

command instead.

You must have root privileges to use the reboot command.

The format for the reboot command is:

reboot [-lnq]

The descriptions of the various reboot options are shown in

Table 3–4.

System Shutdown and Startup 3–9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-125-320.jpg)

![Digital UNIX Initialization Files

Example 3–4 An /sbin/rc2 File

trap "echo" 2 1

PATH=/sbin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin

export PATH

# Just exit if /usr not mounted.

if [ ! -d "/usr/sbin" ] 2

then

exit

fi

# Determine action from runlevel information

set ‘who -r‘ 3

if [ $9 = "S" ]; then 4

stty sane tab3 2>/dev/null

echo "The system is coming up. Please wait..."

BOOT=yes

elif [ $7 = "2" ]; then 5

echo "Changing to system level 2."

if [ -d /sbin/rc2.d ]; then

for f in /sbin/rc2.d/K*

do

if [ -s $f ]; then

/sbin/sh $f stop

fi

done

fi

fi

if [ -d /sbin/rc2.d ]; then 6

for f in /sbin/rc2.d/S*

do

if [ -s $f ]; then

/sbin/sh $f start

fi

done

fi

if [ "$BOOT" = "yes" -a $7 = "2" ]; then 7

echo "The system is ready."

elif [ $7 = "2" ]; then 8

echo "Change to state 2 has been completed."

fi

An explanation of the /sbin/rc2 script file follows:

1 The trap prevents an interrupt from killing the script.

2 If the /usr/sbin directory is not mounted, terminate execution

of this script. The /usr/sbin directory contains commands

executed by the script files in /sbin/init.d.

3 Use the who -r command to determine the current system run

level.

4 If the change is from single user mode (parameter 9 is "S") we

must be booting to run level 2 or 3.

Reset the console terminal to a reasonable value and

redirect error output to the bit bucket.

Echo the message that the system is coming up to the

console terminal.

System Shutdown and Startup 3–25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-141-320.jpg)

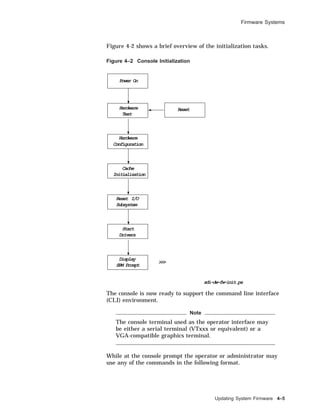

![Firmware Systems

>>> command [-flags] [parameters ...]

Examples of console commands are:

>>> sh auto

AUTO_ACTION = HALT

>>> sh bootdef_dev

BOOTDEF_DEV = DKA300

>>> sh boot_osflags

BOOT_OSFLAGS = A

SRM

Commands

and Tasks

System management task support is provided through the

SRM console allowing the operator or user to customize the

environment or take special actions. Table 4-1 briefly lists some

of these tasks with the command used.

Table 4–1 Administrator Tasks

Task Command

Boot the operating system

software

boot

Change the default startup action set auto_action

Initialize the system init

Set the default operating system set os_type

Display the system configuration show config

Invoke the ARC console firmware arc

There are certain system management tasks that can only be

performed using the SRM console.

• The test command to test the system

• The show fru command (field replaceable unit) to examine

system bus options for errors

• To set or change certain environment variables such as enable

multiple CPUs or fast SCSI devices as an example

Note

For a complete SRM console command list with

explanatory information consult your Firmware Reference

Guide for the hardware platform required. For example,

AlphaServer 2000/2100, or DEC3000 M500.

4–6 Updating System Firmware](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-156-320.jpg)

![Common Desktop Installation

Selection Kernel Option

--------------------------------------------------------------

1 System V Devices

2 Logical Volume Manager (LVM)

3 NTP V3 Kernel Phase Lock Loop (NTP_TIME)

4 Kernel Breakpoint Debugger (KDEBUG)

5 Packetfilter driver (PACKETFILTER)

6 Point-to-Point Protocol (PPP)

7 STREAMS pckt module (PCKT)

8 X/Open Transport Interface (XTISO, TIMOD, TIRDWR)

9 File on File File System (FFM)

10 ISO 9660 Compact Disc File System (CDFS)

11 Audit Subsystem

12 ACL Subsystem

13 All of the above

14 None of the above

15 Help

--------------------------------------------------------------

Enter the selection number for each kernel option you want.

For example, 1 3 [14]: 6

You selected the following kernel options:

Point-to-Point Protocol (PPP)

Is that correct? (y/n) [y]: y

Do you want to edit the configuration file? (y/n) [n]:

The system will now automatically build a kernel

and then reboot. This will take approximately 15

minutes, depending on the processor type.

When the login prompt appears after the system

has rebooted, use ’root’ as the login name and

the SUPERUSER password that was entered during

this procedure, to log into the system.

*** PERFORMING KERNEL BUILD ***

Working....Thu Feb 29 13:01:10 EST 1996

Working....Thu Feb 29 13:03:11 EST 1996

Error opening license database /var/adm/lmf/ldb

lmf: No such file or directory

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

%IT STOP% Thu Feb 29 12:55:40 EST 1996

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

Post

Installation

Login and

Setup

When you log in to the system (with graphics capability) for the

first time, the CDE login window is displayed. Enter root as

the username and then enter the root password specified at the

beginning of the installation. The display window created has

four components:

• A Help Viewer window, Introducing the Desktop

• A Pop-up window labeled: Action Required

5–18 Installing the System](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-182-320.jpg)

![Performing an Update Installation

Example 5–2 (Cont.) Update Installation Log

Working....Mon Feb 28 15:01:22 EST 1994

The Digital UNIX 4.0 Update Installation will update the

following Digital UNIX products:

Digital UNIX V3.2C

Digital Equipment Corporation recommends that you perform complete

system software backups before proceeding.

Press RETURN to review message again.

Do you want to continue the update installation? (y/n) []:y 5

****** Checking current state of system

Depending on the system configuration, this may take

up to 20 minutes...

Working....Mon Feb 28 15:04:02 EST 1994

Working....Mon Feb 28 15:06:02 EST 1994

Working....Mon Feb 28 15:08:02 EST 1994

Working....Mon Feb 28 15:12:02 EST 1994

Working....Mon Feb 28 15:15:02 EST 1994

Working....Mon Feb 28 15:18:02 EST 1994

Unprotected customized system files have been found on

this system and have been saved to ’filename.PreUPD’.

A listing of the files has been logged in

/var/adm/smlogs/upd_custom_files. 6

After the update installation has completed, use the

Update Administration Utility (/usr/sbin/updadmin)

to perform system administration tasks on these files.

****** Updating system to Digital UNIX V4.0

Working....Mon Feb 28 15:23:02 EST 1994

Base System

Copying from /dev/rz4c

Working....Mon Feb 28 15:26:11 EST 1994

Verifying

Working....Mon Feb 28 15:28:02 EST 1994

Base System - Hardware Support

Copying from /dev/rz4c

Working....Mon Feb 28 15:33:19 EST 1994

Verifying

Working....Mon Feb 28 15:35:02 EST 1994

Compiler Backend

Copying from /dev/rz4c

Working....Mon Feb 28 15:36:19 EST 1994

Verifying

Working....Mon Feb 28 15:37:02 EST 1994

Kernel Header and Common Files

Copying from /dev/rz4c

Working....Mon Feb 28 15:38:19 EST 1994

Verifying

Working....Mon Feb 28 15:38:59 EST 1994

(continued on next page)

5–22 Installing the System](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-186-320.jpg)

![Performing an Update Installation

If you choose t, the updadmin utility prompts:

Enter the name of the tape backup device (for example: /dev/nrmt0h)

that you want to use to back up customized files, or press RETURN

to go back to the previous menu:

Deleting Files If you choose d from the File Admin menu to delete files, updadmin

looks to see if the files were backed up. If they were not, it

displays a message similar to:

==================================================================

Back up customized files not detected.

If you have not backed up the customized files yet, please do so at

this time by answering ’no’ to the question below and selecting the

’s’ option from the previous menu:

===================================================================

Please confirm your intent to delete customized system files

from the system. [y/n]:

Viewing Files The view option displays a list of files based on your updadmin

main menu selection. If you choose to display Unprotected

Customized files, updadmin lists files by Digital UNIX subset name

similar to:

============================================

== Unprotected Customized OSFBASE Files

============================================

./usr/sbin/setup.PreUPD (DELETED FROM SYSTEM)

./etc/zoneinfo/Australia/South.PreUPD (DELETED FROM SYSTEM)

=============================================

== Unprotected Customized OSFINET Files

=============================================

./usr/sbin/screend.PreUPD (DELETED FROM SYSTEM)

./usr/named.PreUPD (DELETED FROM SYSTEM)

Enter ’r’ to review files again, or press RETURN to go back

to the previous menu:

5–26 Installing the System](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-190-320.jpg)

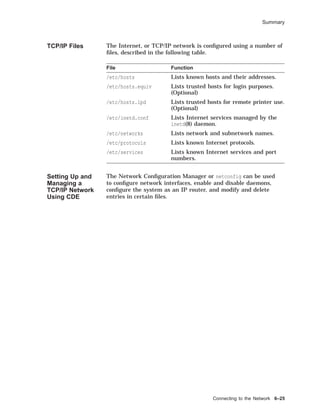

![TCP/IP Files

TCP/IP Files

Overview The Internet, or TCP/IP network, is configured using a number of

files, as described in the table.

Table 6–2 TCP/IP Network Files

File Function

/etc/hosts Lists known hosts and their addresses.

/etc/hosts.equiv Lists trusted hosts for login purposes.

(Optional)

/etc/hosts.lpd Lists trusted hosts for remote printer use.

(Optional)

/etc/inetd.conf Lists Internet services managed by the

inetd(8) daemon.

/etc/networks Lists network and subnetwork names.

/etc/protocols Lists known Internet protocols.

/etc/services Lists known Internet services and port

numbers.

There are also a number of daemons used in TCP/IP networking:

inetd Internet service daemon. When it receives a service

request, it invokes a process to service the request.

rwhod Daemon maintains the database used by rwho(1) and

ruptime(1). It periodically queries the state of the

system and broadcasts it to other systems; it receives

status broadcasts and stores status in the /var/rwho

directory.

routed Daemon manages network routing tables.

Hosts File The /etc/hosts file contains a list of the known hosts on the

network.

Each host is listed on a separate line with fields separated by

blanks. The format is:

address hostname [alias . . . ]

#

# Host Database

#

127.0.0.1 localhost

128.12.5.2 tinker

128.12.5.1 TAILOR tailor taylor

128.12.5.3 SOLDIER soldier

128.12.7.2 SPY007 spy

6–12 Connecting to the Network](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-206-320.jpg)

![TCP/IP Files

The host file allows the system to look up the Internet address,

given a host name. The system administrator can edit this file

and add or remove entries to add or remove a host system on the

network.

A system on a busy network might have an /etc/hosts file

hundreds of lines long. It is not practical to keep this type of

list up to date. Many systems now use the Internet Domain

Name Service (implemented by BIND), where a name server

dynamically provides the host name to address lookups.

The UNIX term host is equivalent to node in DECnet terminology.

Trusted Hosts

File

The /etc/hosts.equiv file specifies which hosts are trusted on

your system. This is a systemwide file maintained by the root

user.

This file:

• Has impact on only the local host.

• Allows a user from a remote system to:

Log in to the same account on your system without a

password (using rlogin)

Copy a file from your system (using rcp)

Execute a command on your system (using rsh)

Enter one system name and optional user names per line.

# Trusted hosts

tailor joe sam

spy

The ~/.rhosts file allows an individual user to specify which hosts

and accounts are trusted on your system in his account.

This file:

• Can exist in each user’s home directory

• Allows a user from a remote system to:

Log in to the same account on your system without a

password (using rlogin)

Copy a file from your system (using rcp)

Execute a command on your system (using rsh)

The file format is:

hostname [username]

Connecting to the Network 6–13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-207-320.jpg)

![TCP/IP Files

Networks File The /etc/networks file allows file hosts on the same network or

subnetwork to be referred to as a group.

• Enter each network on a single line with fields separated by

blanks.

• Format is:

netname netnumber [alias . . . ]

The first field is the network name.

The second field is the network number (just the network

part of the Internet address).

Any remaining fields are aliases.

• Example

# Internet networks

#

loop 127 loopback

engineering 128.12.5 eng

accounting 128.12.7 act

Some commands, such as route(8) will accept a network name as

an argument.

The netstat(1) command can display network names defined in

/etc/networks.

The /etc/networks file is installed with the loop network name.

Other entries are optional.

Protocols File The /etc/protocols file lists the known Internet protocols and

their numbers.

• List each protocol on a separate line along with its protocol

number and any aliases.

# Internet (IP) protocols

#

ip 0 IP # internet protocol, pseudo protocol number

icmp 1 ICMP # internet control message protocol

ggp 3 GGP # gateway-gateway protocol

tcp 6 TCP # transmission control protocol

pup 12 PUP # PARC universal packet protocol

udp 17 UDP # user datagram protocol

• Modify this file to add a protocol to the network.

The protocols file is installed properly when set up for standard

protocols.

If a programmer writes his or her own protocol, it should be

added to /etc/protocols for inetd to manage daemons using it.

Connecting to the Network 6–15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-209-320.jpg)

![Loading and Unloading Software Subsets

Loading and Unloading Software Subsets

Preparing to

Load Software

Digital UNIX software is organized into subsets.

Use the setld(8) command to load and manage software subsets

from a distribution media after installation.

Before loading subsets, you may wish to check for sufficient disk

space:

• Use df to determine disk space.

• Consult the Release Notes for subset sizes and file systems

affected.

Note

setld will automatically check that there is adequate file

space for the subset(s) requested to be installed.

Using the setld

Command

The format for the setld command is:

/usr/sbin/setld [-D dir] -option [location]

[subset...]

• dir is an optional path specifying the destination.

• option includes:

l loads subset from distribution on location and updates

the internal inventory.

d deletes subset from the system and updates the internal

inventory.

i gives an inventory of all subsets known to the system, or

all files for subset.

c configures subset by passing a message to the subset

control program.

x extracts subset from distribution on dev into current

working directory or dir (does not update internal

inventory).

v verifies subset by checking its existence and by running

its installation verification procedure.

Except for the -i option, you must be superuser to run

setld.

• location specifies the distribution location. location can be:

A device special file name: /dev/rz4c—CD–ROM

The name of a directory: /mnt/ALPHA — disk distribution

directory

Loading and Licensing Software 7–3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-225-320.jpg)

![Licensing Your Software

If any data is incorrect, LMF displays the appropriate

error message and gives you an opportunity to reenter the

data.

Example 7–5 shows how to use the lmfsetup command.

Example 7–5 Using the lmfsetup Command

# lmfsetup

Register PAK (type q or quit to exit) [template] Return

Issuer : DEC

Authorization Number : SQM021856

Product Name : OSF-SVR

Producer : DEC

Number of units : 100

Version : 1.0

Product Release Date : 1-MAR-1996

Key Termination Date : 1-APR-1996

Availability Table Code : CONSTANT=100

Activity Table Code :

Key Options : NO_SHARE

Product Token :

Hardware-Id :

Checksum : 1-POFE-IHOI-FHNH-KHDK

Loading and Licensing Software 7–13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-235-320.jpg)

![Solutions

Licensing Your

Software

1.

# lmf list

No entries in license database

2.

# lmf register

(displays template using editor)

Licensed Software Product

Product Authorization Key

Enter data on lines terminated with:

Issuer : DEC

Authorization Number : SQM021856

Product Name : OSF-SVR

Producer : DEC

Number of units : 100

Version : 1.0

Product Release Date : 1-MAR-1996

Key Termination Date : 1-APR-1996

Availability Table Code : CONSTANT=100

Activity Table Code :

Key Options : NO_SHARE

Product Token :

Hardware-Id :

Checksum : 1-POFE-IHOI-FHNH-KHDK

Comment:

Checksum does not validate

Abort (a), Retry with new template (n), Retry with old template (o) ? a

#

3.

# lmfsetup

(prompts each line)

Register PAK (type q or quit to exit) [template] Return

Issuer : DEC

Authorization Number : SQM021856

Product Name : OSF-SVR

Producer : DEC

Number of units : 100

Version : 1.0

Product Release Date : 1-MAR-1996

Key Termination Date : 1-APR-1996

Availability Table Code : CONSTANT=100

Activity Table Code :

Key Options : NO_SHARE

Product Token :

Hardware-Id :

Checksum : 1-POFE-IHOI-FHNH-KHDK

Checksum does not validate

Do you wish to retry? [Yes] N

PAK registration for template canceled

Register PAK (type q or quit to exit) [template] q

#

7–24 Loading and Licensing Software](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-246-320.jpg)

![Building a Static Kernel

Building a Static Kernel

Overview The doconfig program creates a new (or modifies an existing)

system configuration file, creates the special device files for

statically configured drivers, and builds a new Digital UNIX

system kernel.

You need the following Digital UNIX software subsets installed to

rebuild your kernel:

• OSFBINnnn

• OSFBINCOMnnn

nnn corresponds to the operating system version.

Use setld -i to verify that these subsets are installed.

Using the

doconfig

Program

The following example shows how to automatically build a

kernel.

Example 8–2 Building a Kernel with the doconfig Program

1 $ su

2 # cp /vmunix /vmunix.old

3 # cp /genvmunix /vmunix

4 # /usr/sbin/shutdown -r now Boot generic kernel

5 # /usr/sbin/shutdown now To single-user mode

6 # /usr/sbin/doconfig

*** KERNEL CONFIGURATION AND BUILD PROCEDURE ***

*** FILE NAME SPECIFICATION ***

Enter a name for the kernel configuration file. [TINKER] Return

A configuration file with the name ’TINKER’ already exists.

Do you want to replace it? (y/n) [n]: y

. . .

*** KERNEL OPTION SELECTION ***

Selection Kernel Option

---------------------------------------------------------------

1 Streams Socket Coexistence (DLPI & STRIFNET)

2 Data Link Interface (DLI)

3 X/Open Transport Interface (XTISO)

4 ISO 9660 Compact Disc File System (CDFS)

5 All of the above

6 None of the above

---------------------------------------------------------------

Enter the selection number for each kernel option you want.

For example, 1 3 : 4

. . .

(continued on next page)

8–10 Configuring the Kernel](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-258-320.jpg)

![Building a Static Kernel

Example 8–2 (Cont.) Building a Kernel with the doconfig Program

Configuration file complete.

Do you want to edit the configuration file? (y/n) [n]: Return

*** CREATING SPECIAL FILES FOR DEVICES ***

A log file listing special device files is located in /dev/MAKEDEV.log

*** PERFORMING KERNEL BUILD ***

. . .

The new kernel is /sys/TINKER/vmunix.

7 # mv /sys/TINKER/vmunix /vmunix

8 # /usr/sbin/shutdown -r now Boot new kernel

1 You must be the root user to run doconfig and shut down the

system.

2 Optionally, save a copy of the running kernel. If there is not

sufficient space in the root file system, save it elsewhere.

3 When creating a new configuration file or adding new

hardware with doconfig, the system must be running the

generic kernel so that it can recognize all devices.

4 Reboot the system using the generic kernel.

5 Log in as root and shut down the system to single-user mode.

6 Run the doconfig program.

• The script will ask questions about the configuration file

(system) name and time zone and give you the option to

edit the configuration file. (The prompts will be familiar to

anyone who has run the installation script.)

• doconfig builds a new kernel and displays its pathname.

7 Move the new kernel to the root directory.

8 Reboot the system.

Note

If there are problems booting the new kernel, there may

be errors in the configuration file. You can boot the generic

kernel to single-user mode and copy the original kernel

back to /vmunix.

You can build a new kernel from an existing configuration

file by using doconfig with the -c option and the name of the

configuration file to bypass the questions, for example:

doconfig -c TINKER

You do not need to be running the generic kernel, and you need

to reboot only once after moving the new kernel to /vmunix. You

should still save the original kernel before creating a new one.

Configuring the Kernel 8–11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-259-320.jpg)

![Adding Terminals on a Terminal Server

Example 9–2 (Cont.) Using the latsetup Utility

Exit

Initial LAT Setup

Create Additional Devices

Start/Stop LAT

Enable/Disable

LAT Automatic Startup/Shutdown

Undo LAT Setup

To select an option, use the <UP> or <DOWN> arrow keys and press <RETURN>

to enter the chosen submenu. To select options on a horizontal plane use the

<LEFT> or <RIGHT> arrow keys and press <RETURN>. To enter input,

type it in and then press <RETURN>.

Initial LAT Setup

This menu will allow you to setup LAT on your system by creating LAT

special device files, selecting how many getty entries should be placed

into /etc/inittab and choosing whether or not to execute init q. LAT will

be started to allow interactive connections to be made to this system and

a variable will be set in /etc/rc.config so that LAT automatic startup

and shutdown is enabled which will cause LAT to be started each time

this system reaches run-level 3.

Would you like to continue with this option?

YES NO

There are 16 LAT tty devices created.

There are 8 LAT entries already defined in /etc/inittab.

Select style of ttuys to create

SVR4 style ttys

BSD style ttys

How many LAT ttys do you want to create? (0 - 617) [0] 1

How many gettys would you like added to the /etc/inittab file? (0 - 1) [0] 1

NOTE: Please keep your system’s memory resources

in mind when specifying gettys to be added.

Would you like init q to be executed to spawn the new getty entries in

the /etc/inittab file?

YES NO

You requested: 1 tty and 1 getty and that init q be performed.

Are you satisfied with this input?

YES NO

Working on your request.

LAT tty devices have been created and getty entries defined.

There are now 1 LAT tty devices created.

There are now 1 LAT entries defined in /etc/inittab.

Enter <RETURN> to return to main menu

Return

LAT Setup Utility

(continued on next page)

Configuring Peripherals 9–11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-281-320.jpg)

![Adding Terminals on a Terminal Server

Example 9–2 (Cont.) Using the latsetup Utility

The latsetup program provides assistance in setting up LAT on your system.

If this is the first time running latsetup on this system, it is recommended

to select the Initial LAT Setup option.

Exit

Initial LAT Setup

Create Additional Devices

Start/Stop LAT

Enable/Disable

LAT Automatic Startup/Shutdown

Undo LAT Setup

#

Controlling the

LAT Service

The latcp command controls and manages the LAT terminal

service. It allows you to start and stop LAT service and modify

and display configuration characteristics. Some latcp options:

-d Displays LAT host name and status information

-s Starts LAT service; enables connections from LAT

terminal servers to host

-h Halts LAT service

-g group,... Adds group codes to the groups enabled for your

host

-P tty,... Sets a list of ttys as being available only for

host-initiated connections

For example, to set up a host-initiated connection for a printer

connected to a terminal server port:

latcp -A -P tty -H node -R port [-Q]

• tty is the tty device to associate with the printer

• node is the name of the terminal server where the printer is

connected

• port is the name of the port on the terminal server

• -Q does not queue requests if the port is busy

The latcp command on Digital UNIX is similar to lcp on ULTRIX.

An alternative to the example is to specify the node and port in

the /etc/printcap file. Do not specify them in both places.

9–12 Configuring Peripherals](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-282-320.jpg)

![Managing the Print System

This lpd exists as long as there are files in this queue.

Print System

Control

Commands

The following table lists the main commands to control the print

system.

Table 9–1 Print System Commands

Command Function

lp(1) Creates a print request

lpr(1) Creates a print request

lpq(1) Displays a printer queue

lprm(1) Removes print requests from a queue

lpstat(1) Displays printer status

lpc(8) Enables or disables a printer or printer queue;

rearranges the order of jobs in a queue; checks the

status of a printer, a queue and the printer daemon

lptest(8) Generates a test pattern

CDE Print

Manager

Displays print job status, finds a print job (among

known printers), and allows user to select printers

to be displayed in the Print Manager window

See the Reference Pages for more information.

Note

PrintServer printers require special software.

Using

the lptest

Command

The lptest(8) command generates a ripple test pattern of

printable ASCII characters to standard output. It can be used by

anyone to test terminals and printers.

The format for the lptest command is:

lptest [length [count]]

• length specifies the length of the output line; default is 79

characters.

• count specifies the number of output lines; default is 200 lines.

When count is specified, length must also be specified.

To send the test pattern to a printer, you can redirect standard

output

# lptest > /dev/tty02

# lptest | lpr - -P2

The following is an example of the lptest command.

9–22 Configuring Peripherals](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-292-320.jpg)

![Managing the Print System

Table 9–2 Line Printer Control Commands

lpc Command Function

abort {all | printer} Terminates an active spooling daemon on the local host,

then disables printing (preventing new daemons from

starting). This is usually used with start to restart a

hung printer daemon (that is, lpq reports daemon present,

but nothing is printing).

disable {all | printer} Turns off the queue(s). (Sets group execute permission on

the lock file.)

enable {all | printer} Allows spooling on the queue(s). (Removes group execute

permission on the lock file.)

stop {all | printer} Stops the daemon after the current job completes and

disables printing. (Sets owner execute permission on the

lock file.)

start {all | printer} Enables printing and starts a daemon for the printer(s).

(Removes owner execute permission on the lock file.)

restart {all | printer} Attempts to start a new daemon. This is useful when the

daemon fails unexpectedly, leaving jobs in the queue (and

lpq reports "No daemon present").

status [printer] Displays the status of daemons and queues.

up [all | printer] Enables queuing and printing and starts a new daemon.

topq printer [job] [user] Moves jobs to the top of the printer queue.

You need queuing enabled and printing enabled in order to print.

The following example shows some typical lpc commands and the

resulting lpc response.

9–24 Configuring Peripherals](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-294-320.jpg)

![Solutions

Adding

Terminals on

a Terminal

Server

1.

# grep LAT /sys/conf/TINKER

options LAT

2. See the example in the text.

Dynamic

Device

Recognition

1. # more /etc/ddr.dbase

2. # grep drive /sys/conf/yourhostname

Adding a

Printer with

CDE Printer

Configuration

1. Similar to the "remote" example in the text.

2. See the local printer example in the text.

Managing the

Print System

1. Use lptest

a.

# lptest

!"#$%&’()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[]^_‘abcdefghijklmno

"#$%&’()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[]^_‘abcdefghijklmnop

#$%&’()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[]^_‘abcdefghijklmnopq

$%&’()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[]^_‘abcdefghijklmnopqr

%&’()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[]^_‘abcdefghijklmnopqrs

&’()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[]^_‘abcdefghijklmnopqrst

’()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[]^_‘abcdefghijklmnopqrstu

()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[]^_‘abcdefghijklmnopqrstuv

)*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[]^_‘abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvw

.

.

.

b.

# lptest 65 25

c.

# lptest 79 10

d.

# lptest 79 10 >/dev/lp0

2. Use lpc

Configuring Peripherals 9–31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dunix-141227095156-conversion-gate02/85/Dunix-sys-operating-301-320.jpg)