The document provides essential guidelines for writing a literature review, emphasizing the importance of organizing it by two selected themes based on the research question. Each theme should include detailed reviews of three sources, showcasing connections, similarities, and differences in findings while adhering to APA style. It also discusses the structure of the paper, including the introduction, methods, discussion, and conclusion, along with citation and paraphrasing requirements to avoid plagiarism.

![conflict resolution, International Criminal Court, international

criminal law, judicial intervention,

lawfare, prosecutions

Corresponding author:

Alana Tiemessen, Endicott College, 376 Hale St., Beverly, MA

01915, USA.

Email: [email protected]

601201 IRE0010.1177/0047117815601201International

RelationsTiemessen

research-article2015

Article

mailto:[email protected]

https://sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

https:// doi: 10.1177/0047117815601201

https://ire.sagepub.com

410 International Relations 30(4)

The contentious concept of ‘lawfare’ has proliferated to various

foreign policy areas and

permeated a discourse on the function and legitimacy of law in

conflict. Lawfare hap-

pens when legal institutions become coercive and strategic tools

for states and nonstate

actors to pursue a variety of political and operational

objectives. The concept seems

particularly apt to the International Criminal Court’s (ICC)

judicial interventions.1 The

ICC’s interventions have occurred in eight African states so far

and resulted in 22 cases

against notorious perpetrators of atrocity crimes, including

warlords, rebel leaders, polit-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/draftingthelitreview-helpfultipshelpfultipsregardingthe-220922010428-c9d8e51f/75/Drafting-the-Lit-Review-Helpful-TipsHelpful-tips-regarding-the-8-2048.jpg)

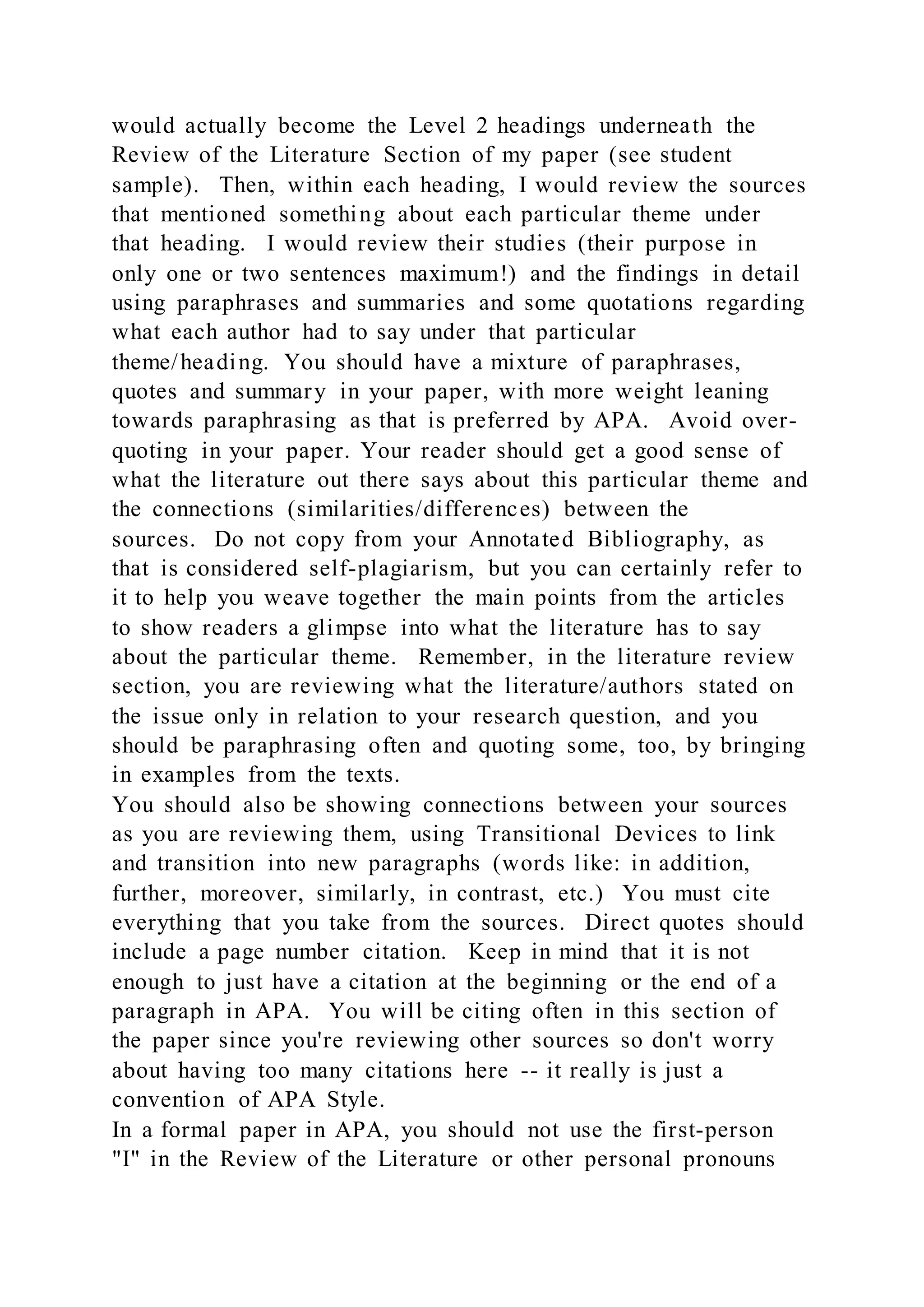

![Professor Amy McBain

January 10, 2020

Commented [BA1]: The full title appears in the upper 1/3

of the title page in title case and centered.

See this link for more information.

https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/paper-

format/title-page

Commented [BA2]: Note that there is a specific context

for the research: a narrowed focus within the larger topic.

Commented [BA3]: The entire APA paper should be

consistently double-spaced (except for the text in tables,

which can be single, 1.5, or double spaced; try and keep

each table on a single page and make them easily readable

for your audience).

Also, be sure to check your Paragraph formatting to make

sure the spacing “Before” and “After” are both set at “0pt.”

https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/paper-

format/title-page

https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/paper-

format/title-page

2

Fall Risk Factors in Hospitalized Acute Stroke Patients: A](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/draftingthelitreview-helpfultipshelpfultipsregardingthe-220922010428-c9d8e51f/75/Drafting-the-Lit-Review-Helpful-TipsHelpful-tips-regarding-the-68-2048.jpg)

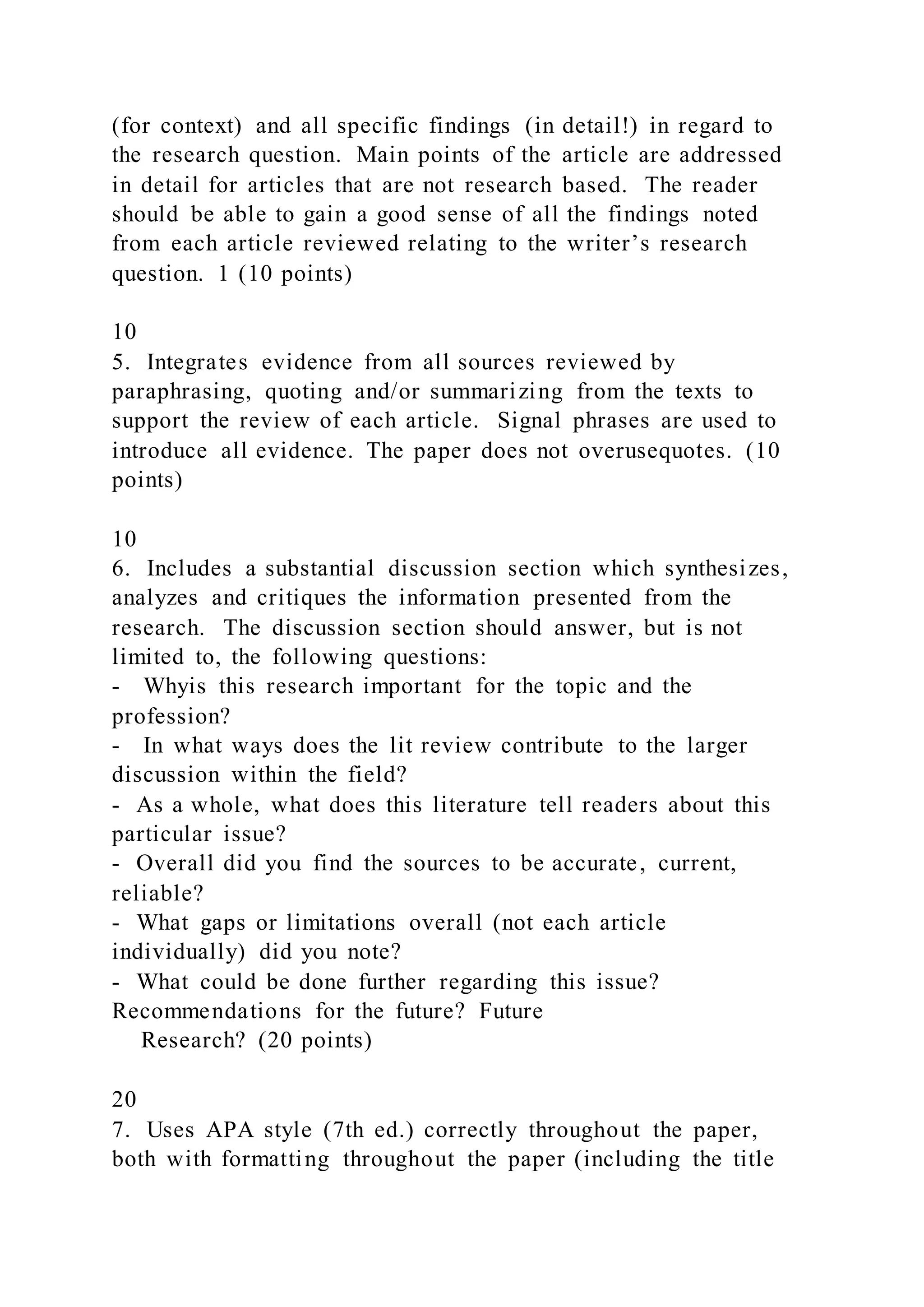

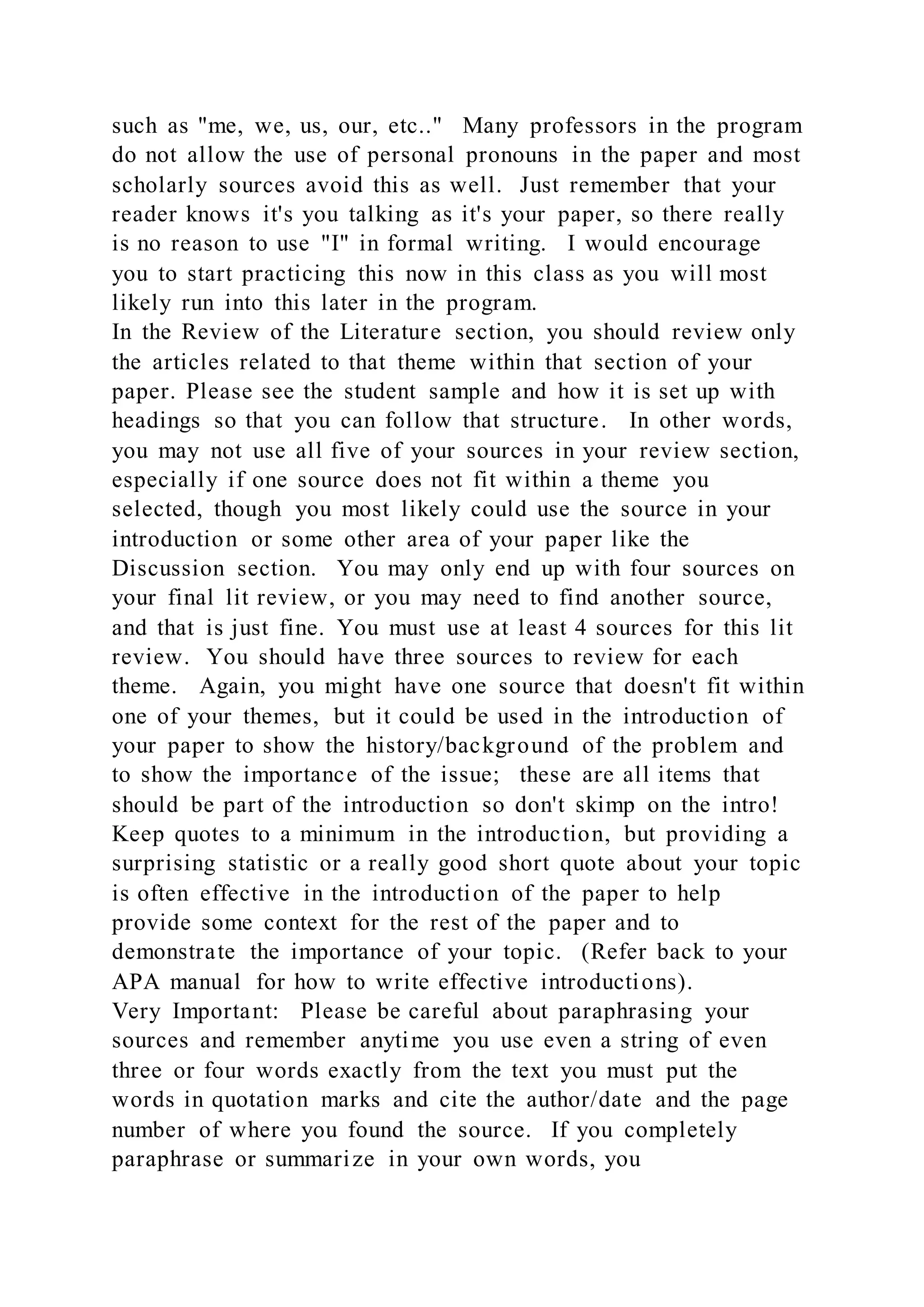

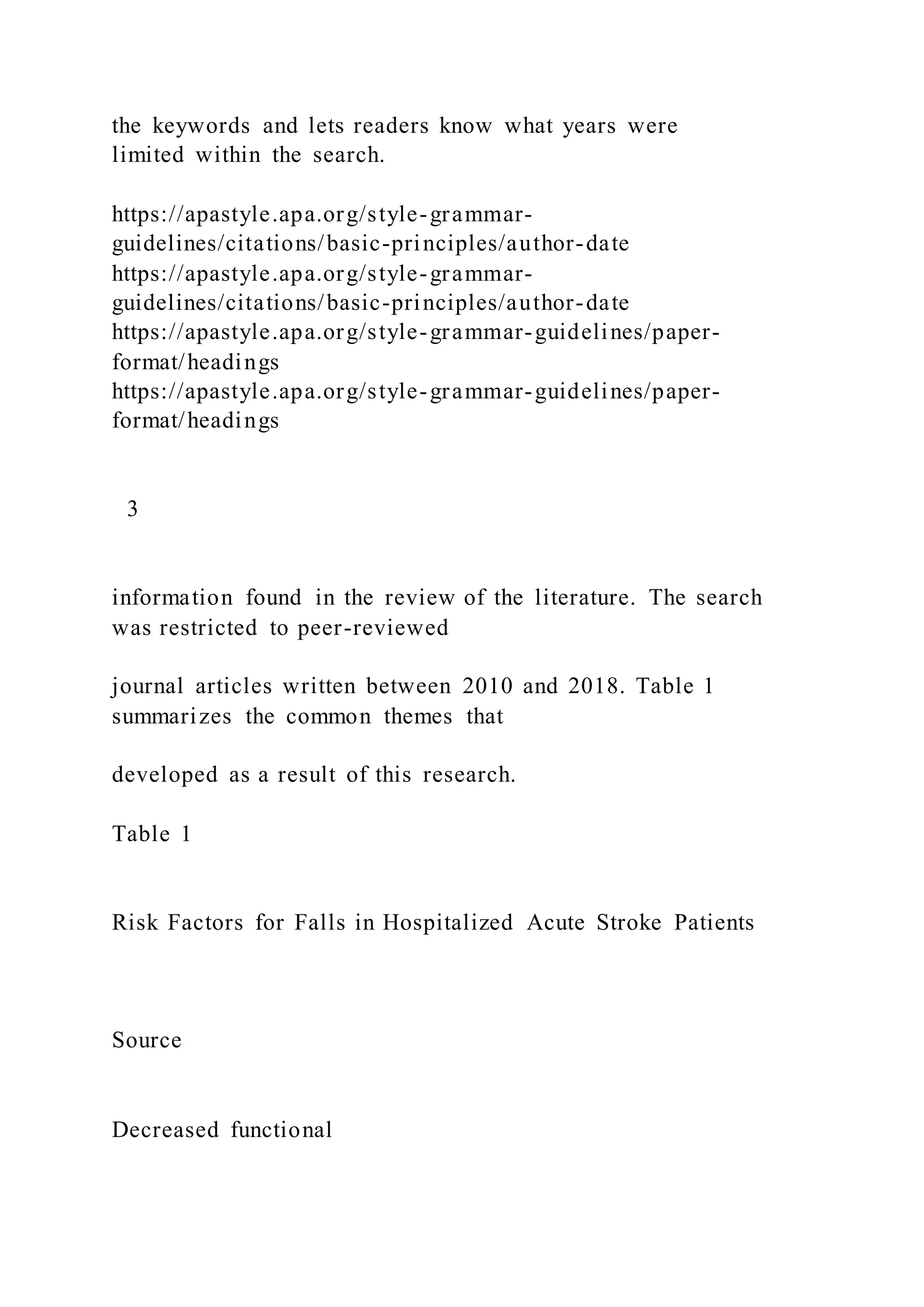

![terms provided definitions to clarify

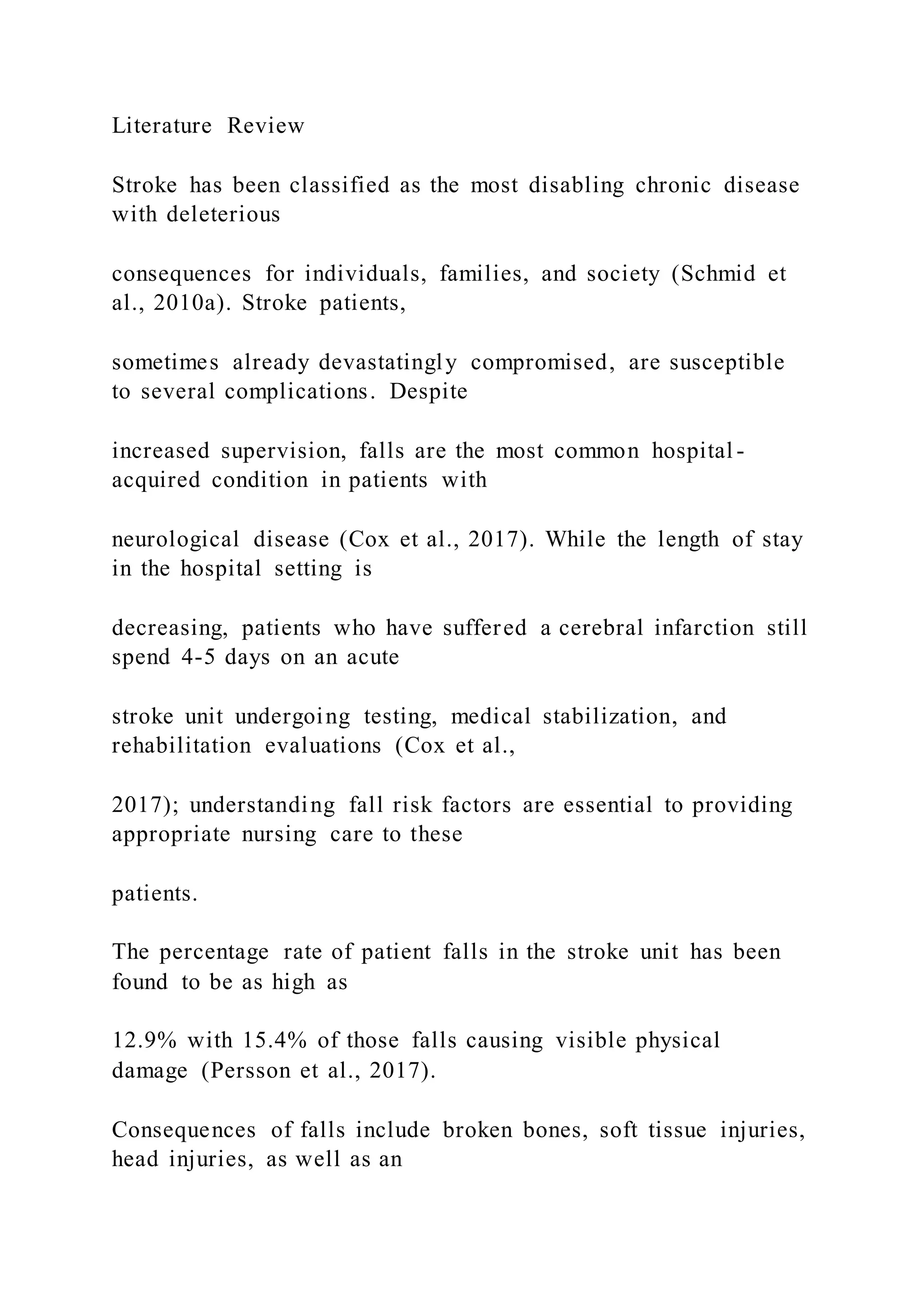

Commented [BA4]: The full title appears bold and

centered as the first line on p. 2 and should be the same

exact wording as appears on the title page.

“introduction” is not used as a heading in APA papers.

Commented [BA5]: When sources have 3 or more

authors, use et al. for in text citations. See this link for the

in-text citation rules and examples.

https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-

guidelines/citations/basic-principles/author-date

Remember “et al.” is a Latin abbreviation for et alli, which

means “and others.” Since alli is abbreviated to al. there is

always a period.

Also, parenthetical in-text citations have a comma between

the authors’ names and the year of publication.

Commented [AM6]: Notice that the introduction

provides information and background about the topic

providing some context for the review that will follow. The

purpose of the paper is clearly noted within the

introduction.

Commented [BA7]: This is the correct formatting for an

APA level one heading.

See this link for more information.

https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/paper-

format/headings

Commented [BA8]: The writer in this section notes the

databases that were used to find all of the sources, notes](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/draftingthelitreview-helpfultipshelpfultipsregardingthe-220922010428-c9d8e51f/75/Drafting-the-Lit-Review-Helpful-TipsHelpful-tips-regarding-the-71-2048.jpg)

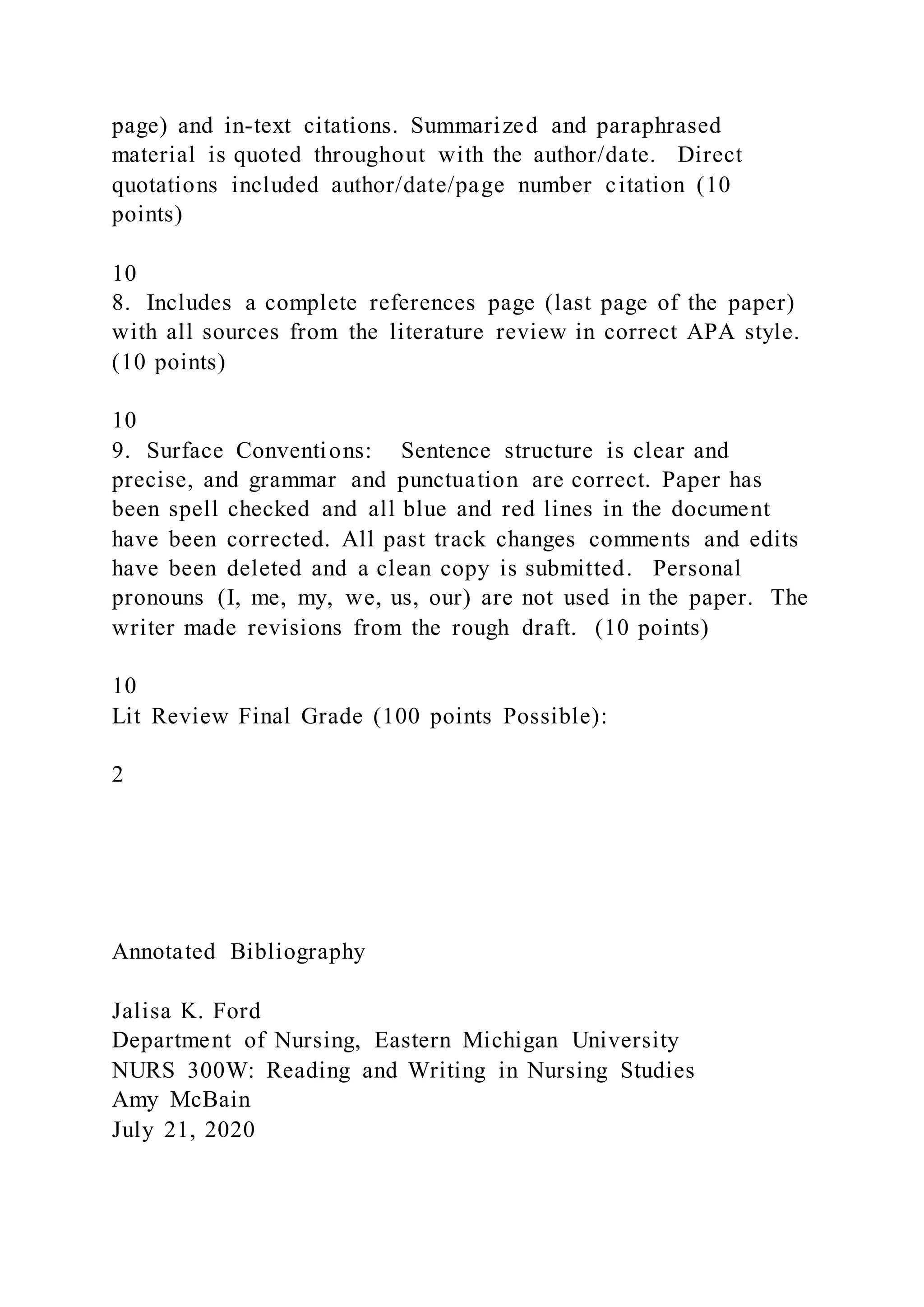

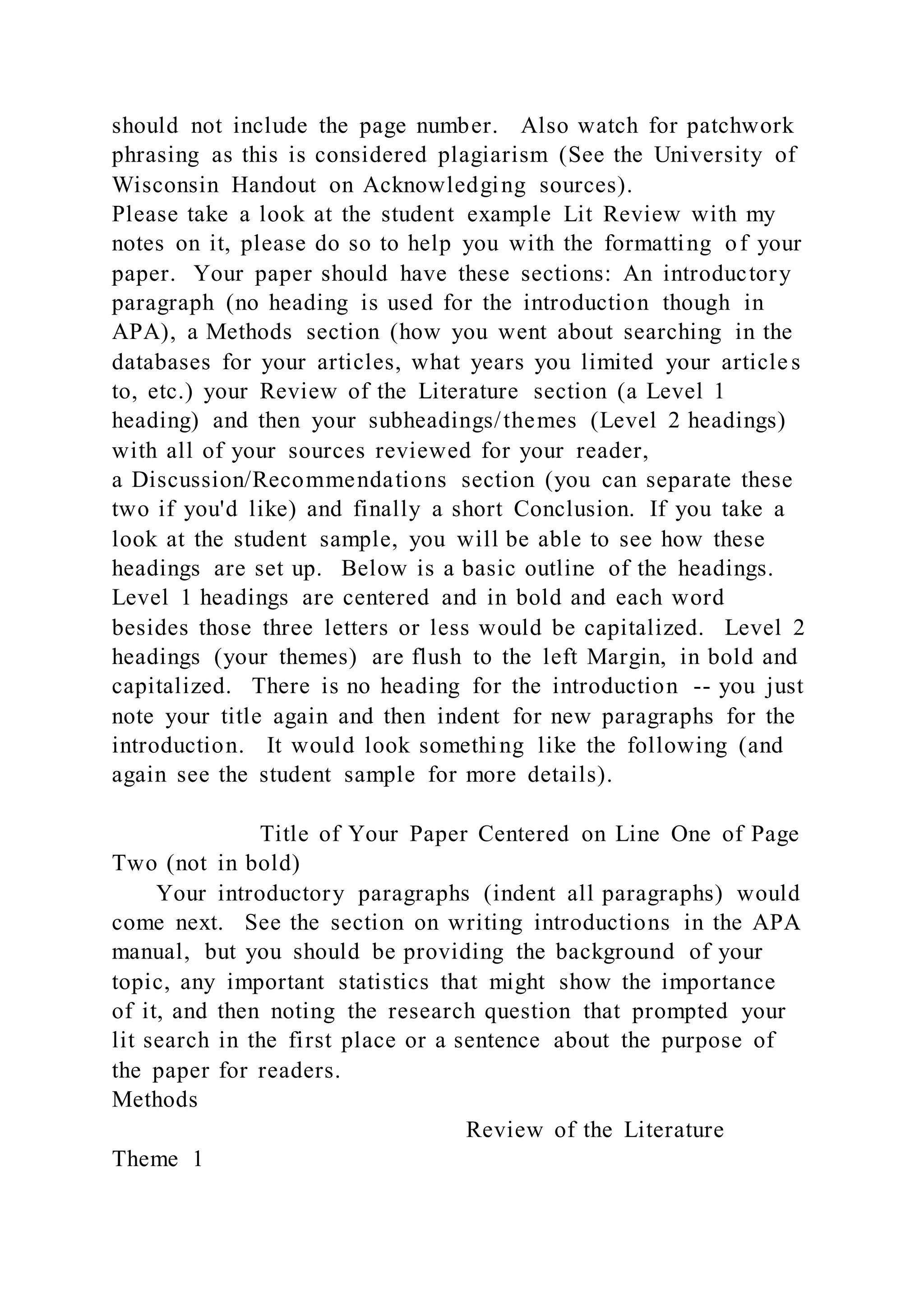

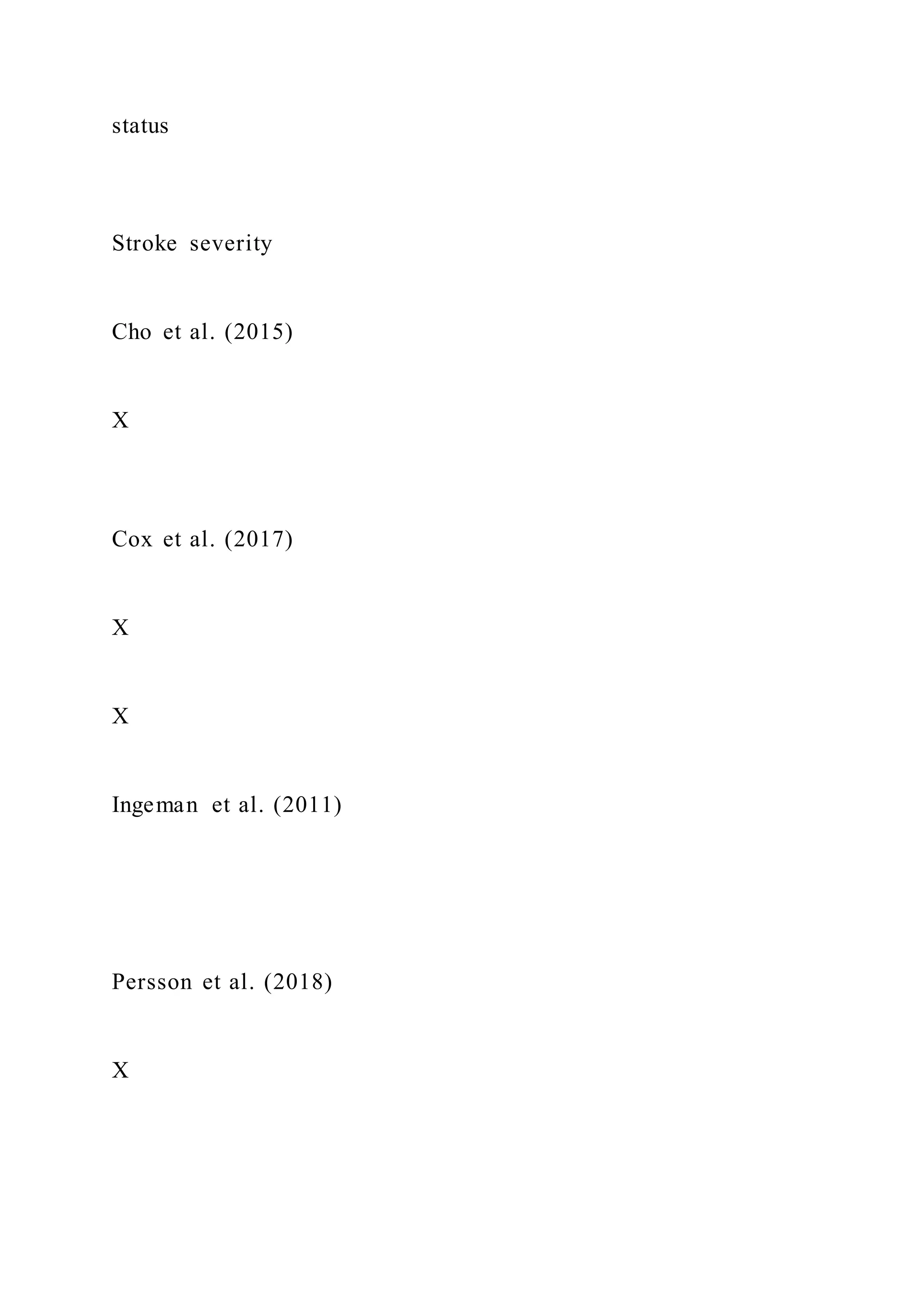

![meet basic needs, fulfill usual roles, and maintain health and

well-being (American Thoracic

Society, 2007). Persson et al. (2018) found that patients who

required the use of a walking aid

such as a cane or walker more than doubled the risk of fall.

Similarly, a study by Cox et al.

(2017) found that patients who needed assistance with

ambulation at the time of discharge were

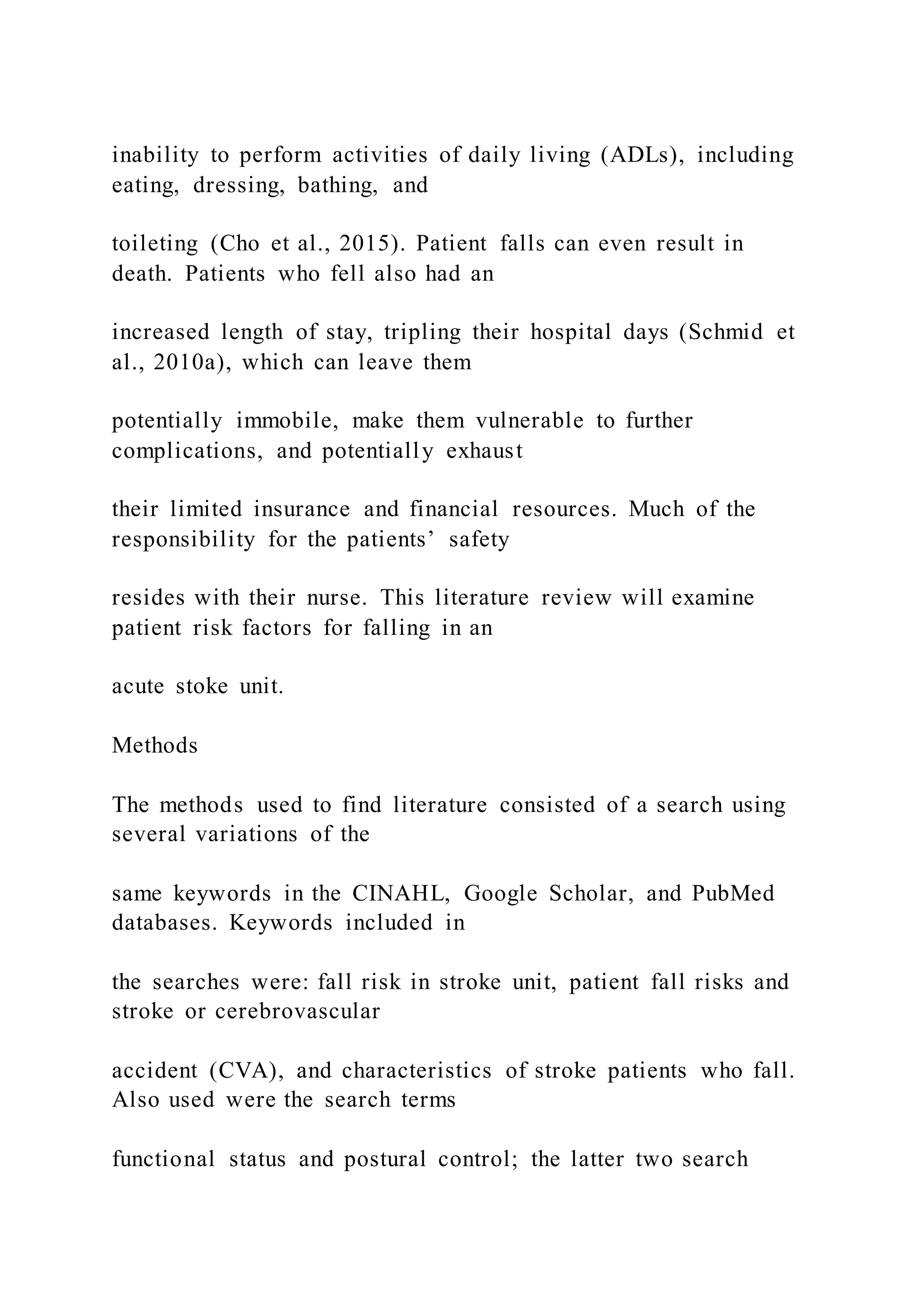

Commented [CS9]: The format is in APA format, with the

label Table 1 above in bold; a title in title case and italicized.

Commented [BA10]: The table has two themes, with at

least three sources per theme; the stub head (see p. 200 in

your APA Manual) is left aligned with the authors listed as

the first citation in text; the column headings are centered

and in sentence case. The authors’ names are alphabetized.

See this resource for more info:

https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/tables-

figures/sample-tables

Commented [BA11]: Use the same font for your tables as

in the rest of your paper; remember consistency in your

document design.

Commented [BA12]: Typically, students include a brief

overview after the Review of Literature heading before the

first theme. The overview would just be 1-3 sentences

indicating why the themes were selected and what the

themes are.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/draftingthelitreview-helpfultipshelpfultipsregardingthe-220922010428-c9d8e51f/75/Drafting-the-Lit-Review-Helpful-TipsHelpful-tips-regarding-the-75-2048.jpg)

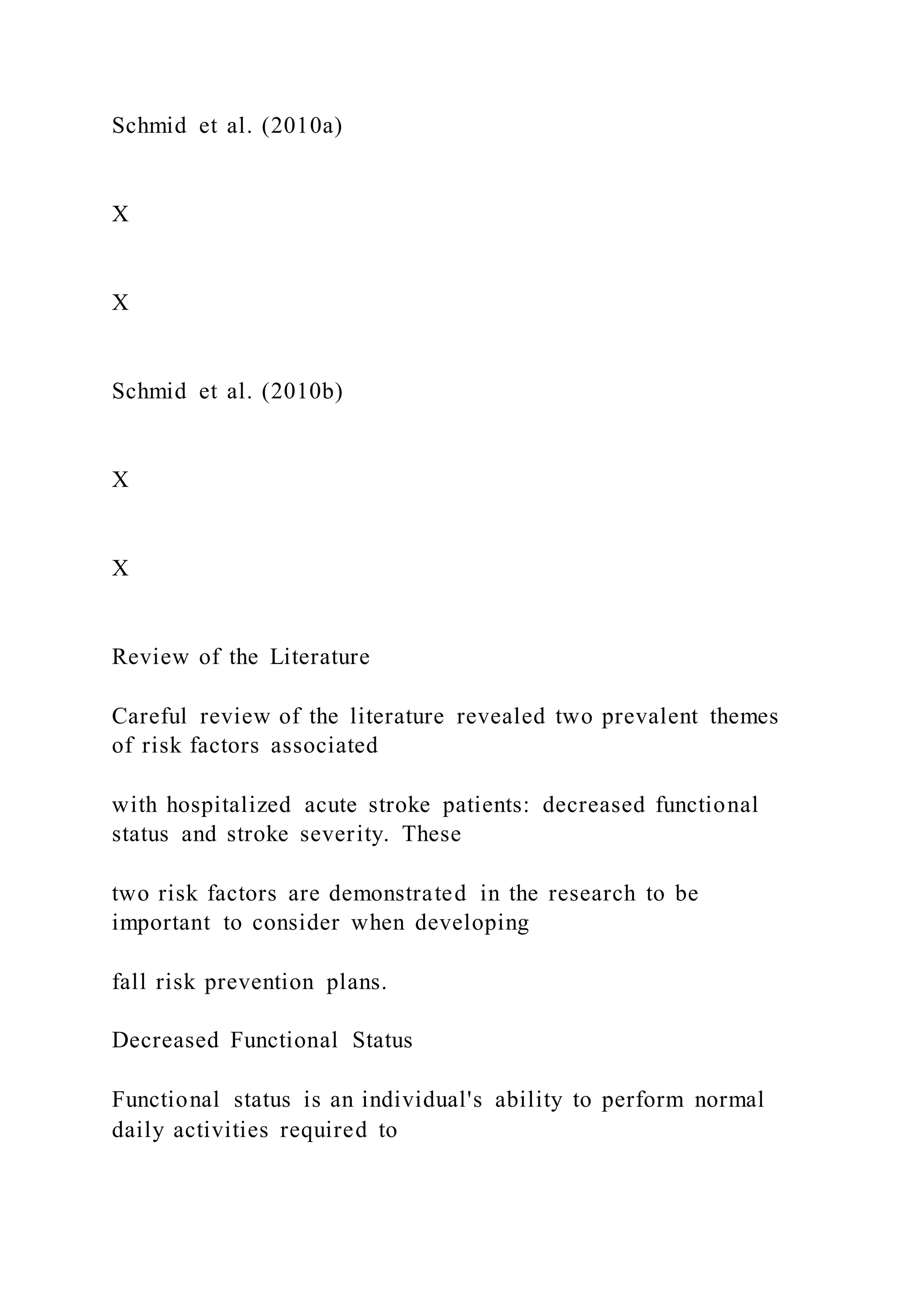

![Commented [BA13]: Notice how the author discussed

these themes below in the same order as presented here to

offer readers parallelism.

Commented [BA14]: This level two heading titles the

section on the first theme. Level two headings are sub-

categories of the level one heading under which they

appear.

Again, see this resource for more on APA headings:

https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/paper-

format/headings

Commented [BA15]: Notice how the topic sentences are

about ideas instead of individual sources. The topic

sentence should provide your readers with an introduction

to this topic and an overview of the main points of this

paragraph.

https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/tables-

figures/sample-tables

https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/tables-

figures/sample-tables

https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/paper-

format/headings

https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/paper-

format/headings

4

statistically more likely to have experienced falling in the

inpatient setting. Schmid et al. (2010b)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/draftingthelitreview-helpfultipshelpfultipsregardingthe-220922010428-c9d8e51f/75/Drafting-the-Lit-Review-Helpful-TipsHelpful-tips-regarding-the-76-2048.jpg)

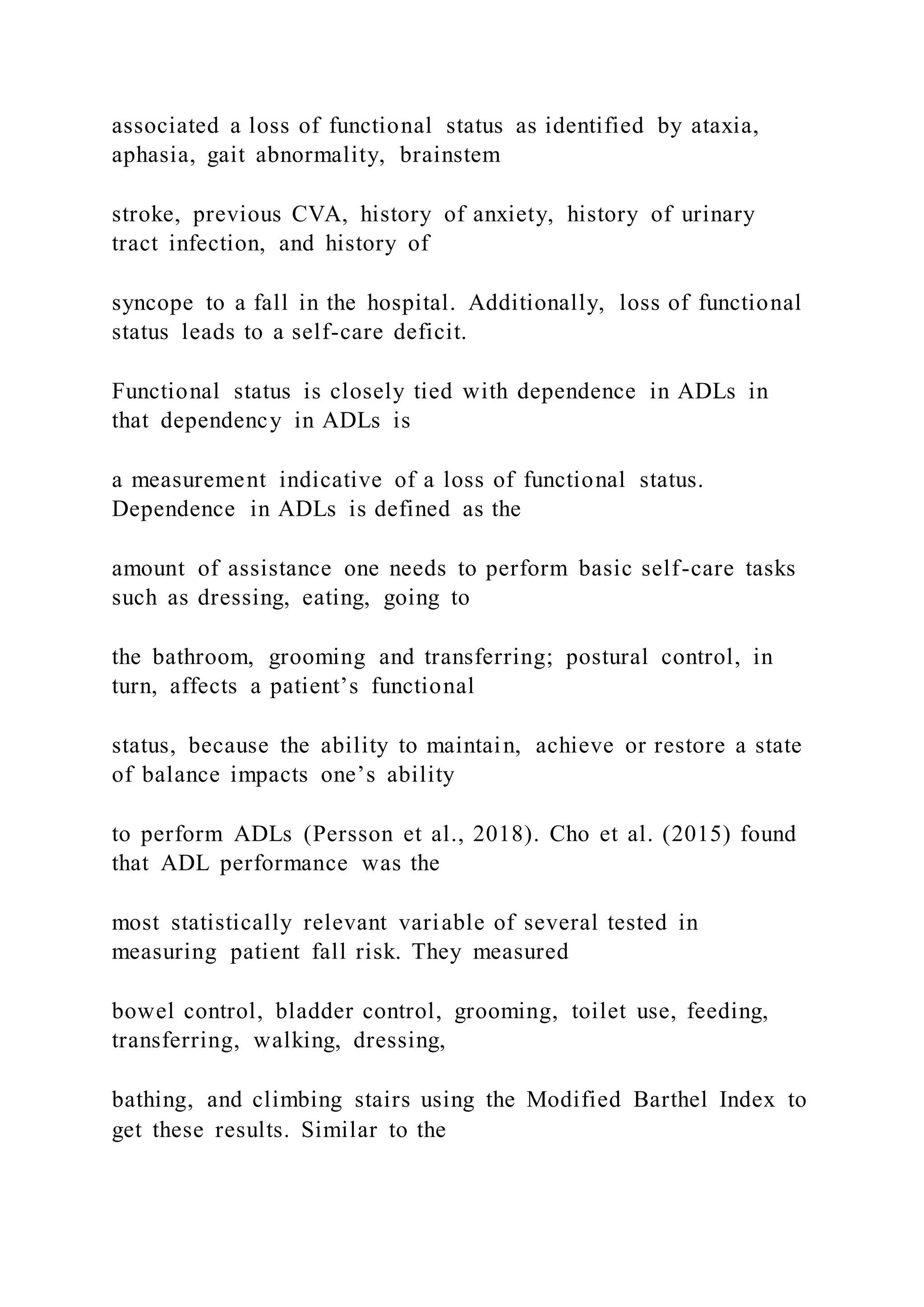

![with the highest possible score

Commented [BA16]: Connections and transitions lead

the reader from one idea to the next.

See the tables on these websites as useful tools listing

transitions and the relationships they establish:

https://owl.purdue.edu/engagement/ged_preparation/part

_1_lessons_1_4/transitions.html

https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/transitions/

Commented [BA17]: A key finding is presented clearly

here.

Commented [BA18]: The methods are smoothly

integrated into the paragraph and do not overtake the

discussion. One sentence should be enough to describe the

methods for the lit review paper.

Commented [BA19]: Unlike the annotated bibliography

where each source is addressed one paragraph at a time, in

the literature review, each paragraph contains references to

many sources that are related and synthesized according to

thematic connections.

Commented [BA20]: The expected finding is

contextualized here.

Commented [BA21]: In the first reference to an

organization, the name is fully spelled out with the acronym

following in parentheses.

Commented [BA22]: This author clearly defines](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/draftingthelitreview-helpfultipshelpfultipsregardingthe-220922010428-c9d8e51f/75/Drafting-the-Lit-Review-Helpful-TipsHelpful-tips-regarding-the-79-2048.jpg)

![important information before digging into the results to

provide context for the reader and the significance of the

research.

Commented [BA23]: In the second and each subsequent

reference to an organization, just the acronym is used.

https://owl.purdue.edu/engagement/ged_preparation/part_1_less

ons_1_4/transitions.html

https://owl.purdue.edu/engagement/ged_preparation/part_1_less

ons_1_4/transitions.html

https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/transitions/

5

being 42; a stroke scale score of greater than 8, which indicates

a moderate to severe stroke, was

associated with a risk of falling while in the acute hospital

phase of recovery (Schmid et al.,

2010a). Similarly, a study conducted on outpatients using data

from both their inpatient medical

records and current outpatient assessments found that those with

a higher stroke scale were at

greater risk for falls. To give an example, of that high-risk

group those with a stroke scale score

of greater than 4 had the highest risk for falls (Schmid et al.,

2010b). Cox et al. (2017) found that

patients who presented with new onset weakness as a symptom](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/draftingthelitreview-helpfultipshelpfultipsregardingthe-220922010428-c9d8e51f/75/Drafting-the-Lit-Review-Helpful-TipsHelpful-tips-regarding-the-80-2048.jpg)

![with NIHSS scores of 8 and over which may lead to a decrease

in falls in the latter stages of

recovery. Schmid et al. (2010b) argue for the use of a

neuroscience specific fall risk assessment

tool. The risk factors discussed in this review—functional status

and dependency in ADLs—are

very closely related to each other and to the items in the NIHSS

score suggesting that the NIHSS

score may be used as a quick snapshot of fall risk.

Commented [BA24]: Sources do not have to agree or

have the same findings to be connected thematically in the

literature review. Pointing out the differences in results is

important to educating the reader on the issue, too.

Commented [BA25]: This shows a nuanced look at the

limitations of the research.

Commented [BA26]: Notice how robust of a section this

author’s Discussion section is.

Commented [BA27]: This point responds to the question:

“Why is this research important for the issue presented and

to the nursing profession?”

Commented [BA28]: Calling attention to important

elements in the research allows the writer to highlight ideas

that are central to the research question explored. It also

responds to the question: “In what ways does the literature

review contribute to the larger discussion within the field?”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/draftingthelitreview-helpfultipshelpfultipsregardingthe-220922010428-c9d8e51f/75/Drafting-the-Lit-Review-Helpful-TipsHelpful-tips-regarding-the-82-2048.jpg)

![Commented [BA29]: This point responds to the question:

“As a whole, what does this literature tell readers about this

particular issue?”

6

There is little research addressing the issue of patient falls in

an acute stroke unit setting.

Most studies focus on patients in a rehabilitation setting or

patients living in the community after

returning home. Two studies used in this review, in fact, used

data from both an acute hospital

setting and that of either rehabilitation or home. At least one of

the studies excluded patients who

had received tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) and

endovascular procedures such as

mechanical thrombectomy and intra-arterial TPA. These

patients represent a growing number of

stroke patients and will only increase. A number of existing

studies focusing on the acute

hospitalization period are nearly 20 years old or older.

Therefore, they do not take into

consideration changes in the average length of stay or current

interventions in the treatment of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/draftingthelitreview-helpfultipshelpfultipsregardingthe-220922010428-c9d8e51f/75/Drafting-the-Lit-Review-Helpful-TipsHelpful-tips-regarding-the-83-2048.jpg)

![also warrants further

research. Stroke patients often have more than one chronic

condition. Studies have identified

several diseases that increase fall risk among stroke patients.

However, each study found

different conditions to cause a risk for falls. Schmid et al.

(2010a) found that patients with a

history of anxiety and urinary tract infection were more likely

to fall. Cox et al. (2017) found that

Commented [BA30]: This point responds to the question:

“Are there any limitations or gaps in the research that you

noticed and that need to be addressed?”

Commented [BA31]: This point responds to the question:

“What could be done further regarding this issue?”

Commented [BA32]: This point responds to the question:

“What studies/research do you feel still need to be done in

this area? Be specific here.”

7

males with a history of heart disease or renal insufficiency to be

at a very high risk for falls. The

above conditions were also found to contribute to fall risk in a

large Dutch study that took place](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/draftingthelitreview-helpfultipshelpfultipsregardingthe-220922010428-c9d8e51f/75/Drafting-the-Lit-Review-Helpful-TipsHelpful-tips-regarding-the-85-2048.jpg)

![gender.

Commented [BA33]: The succinct conclusion highlights

the important findings of the literature review while

indicating what research remains to be done.

Commented [BA34]: Connecting the research to practice

is essential.

8

References

American Thoracic Society. (2007). Functional status.

http://qol.thoracic.org/sections/key-

concepts/functional-status.html

Cho, C., Yu, J., & Rhee, H. (2015). Risk factors related to

falling in stroke patients: A cross-

sectional study. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 27(6),

1751-1753.

https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.27.1751

Cox, R., Buckholtz, B., Bradas, C., Bowden, V., Kerber, K., &

McNett, M. M. (2017). Risk

factors for falls among hospitalized acute post-ischemic stroke](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/draftingthelitreview-helpfultipshelpfultipsregardingthe-220922010428-c9d8e51f/75/Drafting-the-Lit-Review-Helpful-TipsHelpful-tips-regarding-the-87-2048.jpg)

![D. M. (2010b). Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of

poststroke falls in acute hospital

setting. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development,

47(6), 553-562.

https://doi.org/10.1682/JRRD.2009.08.013 3

Commented [BA35]: The heading “References” is

centered and bolded.

Commented [BA36]: When the organization that

published the source is also listed as the author, this is the

correct formatting. See this resource for more info:

http://blog.apastyle.org/apastyle/2010/01/the-generic-

reference-who.html

Commented [BA37]: Hanging indents are used for each

source. See this video for instructions:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FBv7gWpOiP4

Commented [BA38]: In APA 7th edition, all DOIs should

be formatted the same way; see this resource for more info

and examples: https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-

guidelines/references/dois-urls

Commented [BA39]: When presenting the title of an

article in a bibliographic entry, you should follow these

conventions: capitalize only the first letter of the first word

of a title and subtitle, the first word after a colon or a dash

in the title, and proper nouns.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/draftingthelitreview-helpfultipshelpfultipsregardingthe-220922010428-c9d8e51f/75/Drafting-the-Lit-Review-Helpful-TipsHelpful-tips-regarding-the-89-2048.jpg)

![Commented [BA40]: The volume number is italicized,

and the issue number is in plain font in parentheses, and

there is no space or label in-between the two.

Commented [BA41]: Sources should be alphabetized, so

this source (which starts with a “P”) would come after

Ingeman, A., Andersen, G., Hundborg, H. H., Svendsen, M.

L., & Johnsen, S. P. (2011) and so on.

At the same time, you should never ever change the order

of the authors’ names from the way they originally appear

on the article—even if they are not in alphabetic order.

Commented [BA42]: Notice the 2010a here versus the

next source’s 2010b—this is necessary because, while

these two sources are not written by the exact same

team of authors (although they do include some of the

same people, i.e. Schmid, when the in-text citations of

this source are used in the body of the paper they will

appear as Schmid et al. (2010a) and as Schmid et al.

(2010b) so your readers can tell these two sources

apart from one another.

More information:

Two or More Works by the Same Author in the

Same Year

If you are using more than one reference by the same

author (or the same group of authors listed in the same

order) published in the same year, organize them in the

reference list alphabetically by the title of the article or

chapter. Then assign letter suffixes to the year. Refer

to these sources in your essay as they appear in your ...

Commented [BA43]: In APA 7th edition, up to 20 authors](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/draftingthelitreview-helpfultipshelpfultipsregardingthe-220922010428-c9d8e51f/75/Drafting-the-Lit-Review-Helpful-TipsHelpful-tips-regarding-the-90-2048.jpg)