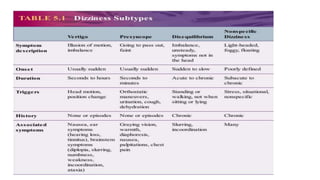

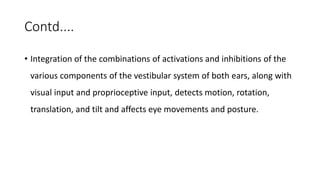

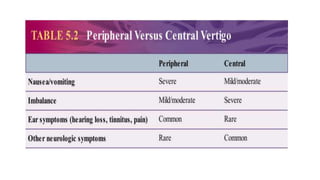

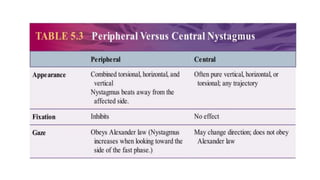

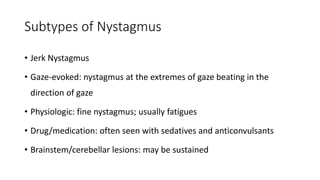

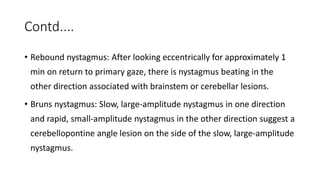

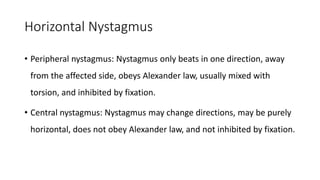

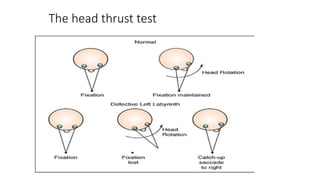

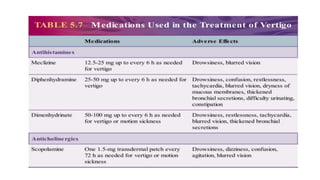

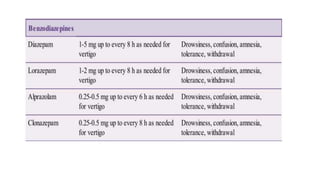

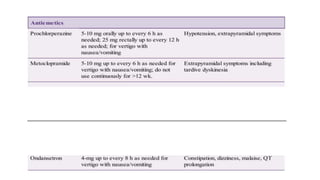

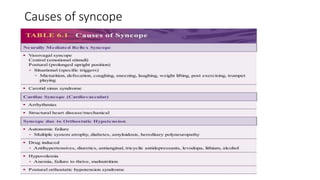

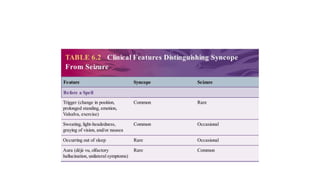

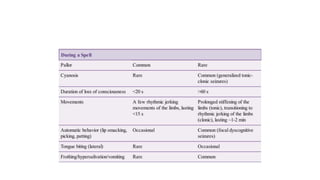

This document discusses dizziness, vertigo, and hearing loss. It begins by defining different types of dizziness and vertigo, and describing the neuroanatomy of the vestibular system. It then discusses various causes of peripheral and central vertigo, methods for diagnosis including examining nystagmus and the head impulse test. Treatment involves addressing the underlying cause, with vestibular rehabilitation and symptomatic medications for attacks. The document also briefly covers syncope, defining it as loss of consciousness from decreased cerebral blood flow versus seizures, with neurally mediated reflex syncope being the most common cause.