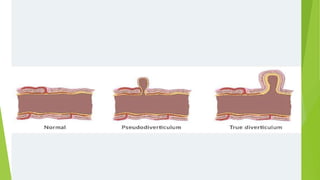

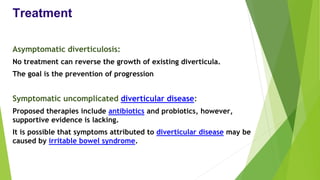

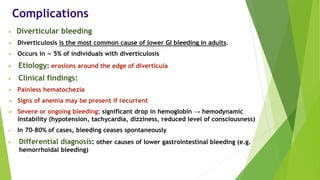

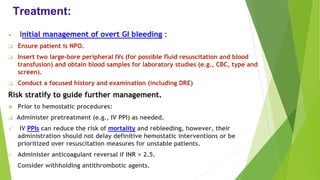

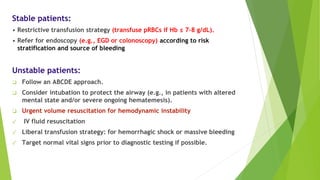

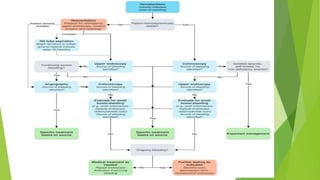

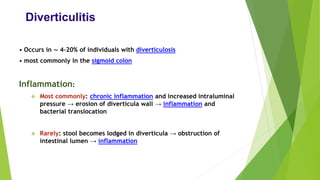

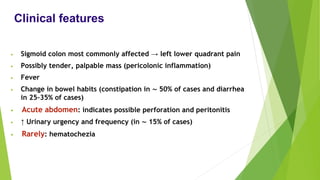

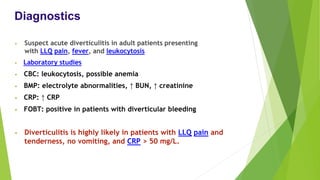

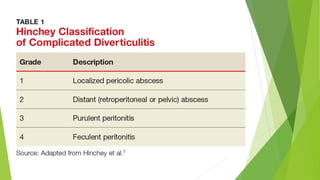

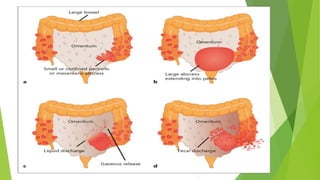

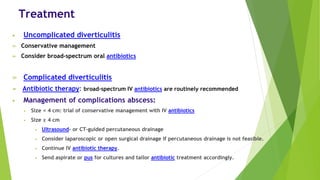

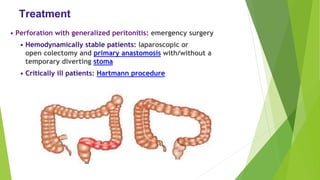

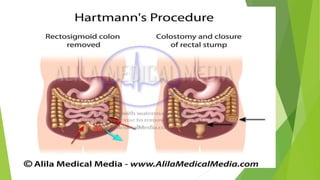

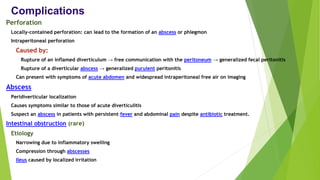

Diverticular disease involves the formation of diverticula in the gastrointestinal tract, which can lead to conditions such as diverticulosis and diverticulitis. Common risk factors include low-fiber diets, obesity, and aging, with symptoms typically ranging from asymptomatic to abdominal pain and bleeding. Diagnosis often involves colonoscopy, and treatment may vary based on the severity, with conservative management recommended for uncomplicated cases, while complicated cases may require surgical intervention.

![diverticular disease [تم حفظه تلقائيا] 3.pptx](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diverticulardisease3-240512203054-95042ff3/85/diverticular-disease-3-pptx-39-320.jpg)