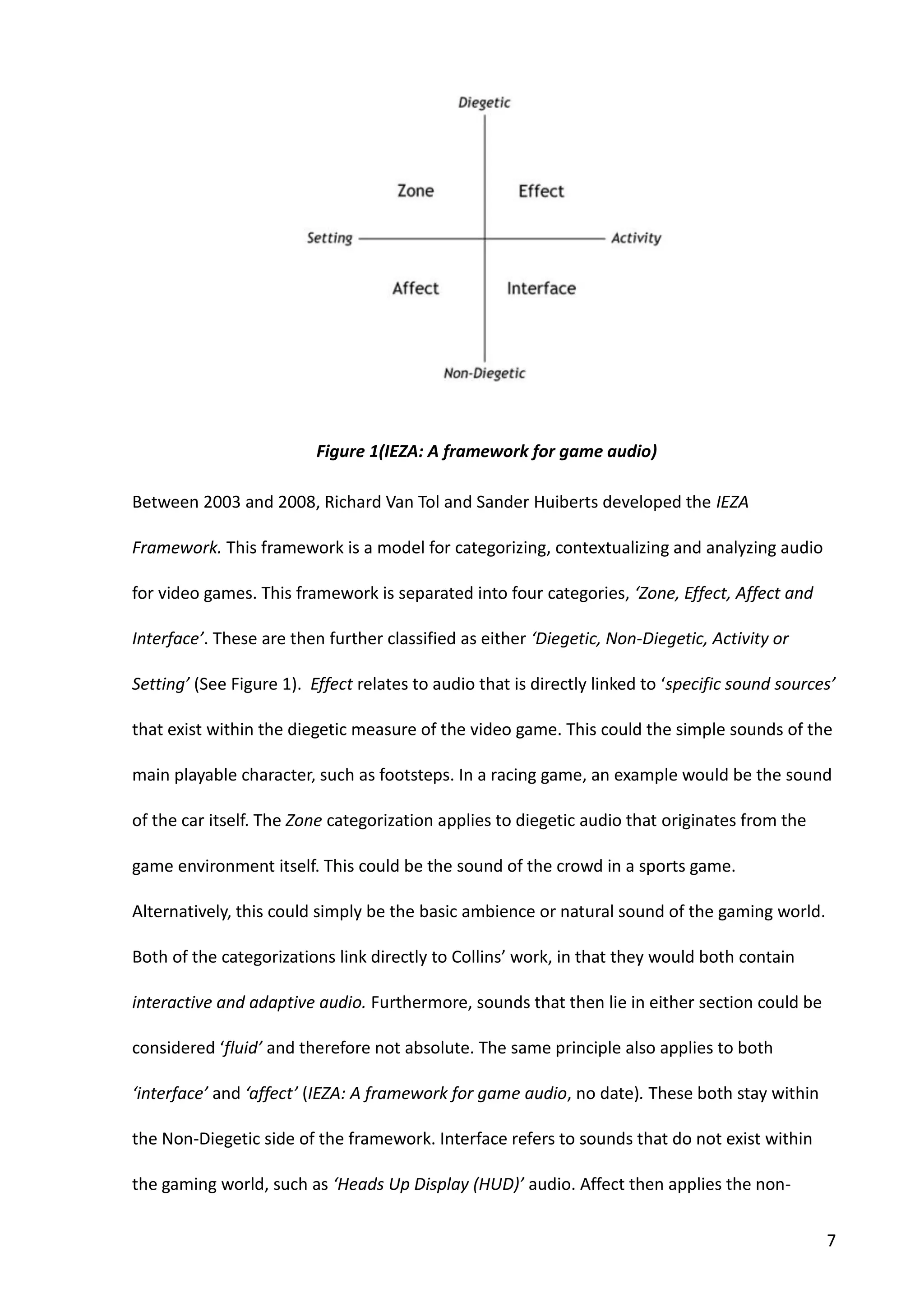

This document is a honors project submitted by Keeran Johnson to the University of St Mark & St John in 2016. It examines how interactive and adaptive audio contributes to immersive gameplay experiences. The document begins by introducing the topic and its importance. It then discusses different frameworks for categorizing game audio, focusing on the works of Collins, Stockburger, Whalen and the IEZA framework. The concept of immersion is also introduced. The document aims to analyze how interactive and adaptive sounds can enhance immersion through case studies and examples.